Abstract

This article demonstrates that the most common prosodic realization of focus can be subsumed typologically under the notion of alignment: a focused constituent is preferably aligned prosodically with the right or left edge of a prosodic domain the size of either a prosodic phrase or an intonation phrase. Languages have different strategies to fulfill alignment, some of which are illustrated in this paper: syntactic movement, cleft constructions, insertion of a prosodic boundary, and enhancement of existing boundaries. Additionally, morpheme insertion and pitch accent plus deaccenting can also be understood as ways of achieving alignment. None of these strategies is obligatory in any language. For a focus to be aligned is just a preference, not a necessary property, and higher-ranked constraints often block the fulfillment of alignment. A stronger focus, like a contrastive one, is more prone to be aligned than a weaker one, like an informational focus. Prominence, which has often been claimed to be the universal prosodic property of focus (see Truckenbrodt 2005 and Büring 2010 among others), may co-occur with alignment, as in the case of a right-aligned nuclear stress, but crucially, alignment is not equivalent to prominence. Rather, alignment is understood as a mean to separate constituents with different information structural roles in different prosodic domains, to ‘package’ them individually.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Selkirk (2009) uses Match constraints, which require that syntactic constituents be contained entirely in prosodic domains. These constraints predict that both edges of a syntactic domain are aligned with edges of the same prosodic domain. A further aspect of her proposal is that it allows recursion of prosodic domains: a syntactic XP entirely contained inside of a larger XP is matched with a φ-phrase entirely contained inside of a larger φ-phrase. Match constraints make different predictions from Wrap, a constraint from Truckenbrodt (1999). Wrap always requires that a syntactic constituent be contained in a single prosodic constituent. It does not demand that a smaller embedded syntactic constituent be contained in a prosodic constituent at the same time. Recursion of prosodic phrases corresponding to recursion of syntactic phrases is generally blocked because of the effect of Nonrecursivity, a constraint explicitly banning recursion of prosodic structure. Nevertheless recursion can be obtained if Align is ranked higher than Wrap and Wrap is still active by being ranked lower than Nonrecursivity (see Truckenbrodt for Kimatuumbi). In Selkirk’s approach (as in mine here), recursion is the default outcome, whereas in Truckenbrodt’s Wrap approach, it is the marked case.

McCarthy (2003) compares gradient alignment constraints with absolute/categorical ones, and shows that gradience can be eliminated from grammar. Following his proposal, all constraints used here are interpreted in an absolute way: if an element is not aligned, it is marked with one violation mark, regardless of the number of elements separating it from the edge.

Two further conditions (selection and confirmation) were also recorded but are not considered here.

Altogether, 18 languages have been tested with Anima. The experimenter was in most cases a native speaker who is trained as a linguist. The languages not addressed in this paper are Greek, Yucatec Maya, Mawng, Quebec French, American English, Mandarin Chinese, Dutch, Prinmi, Arabic, North Sotho, and Aja. The data are available online (http://www.sfb632.uni-potsdam.de/~d1/annis/).

“Right dislocated phrases are easily recognized because they can be doubled by a clitic, may freely follow locative and temporal adjuncts, are always preceded by an intonational break, and can be preceded by an optional pause (here represented by a comma). Crucially, focus must always precede right dislocated constituents” (Samek-Lodovici 2005:703).

Cleft sentences do not always have this prosodic form in French. They can also be eventive sentences and be realized in one ι-phrase. These latter sentences differ from the one shown in (15a).

The constraint Subject is low ranking in Italian, and adding it below Head-ι-R does not modify the tableau T1.

The notions of syntactic inputs and syntactic candidates in OT are far from being resolved issues. Here I follow Hamlaoui (2009a, 2009b) in assuming that the input is best understood as a predication without numeration and without linearization. In this way, cleft sentences are allowed in the set of candidates.

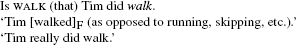

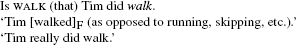

A similar construction to the cleft formation resulting in focus alignment to the right of an φ-phrase illustrated for French is the so-called Predicate Cleft, which involves copying and fronting of a predicate. It is found in Trinidad dialectal English (Cozier 2006), where Predicate Cleft expresses contrastive or verum focus on the verb.

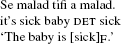

-

(i)

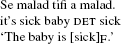

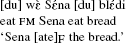

In Haitian Creole (Piou 1982), a focused predicate is also copied and fronted; see (ii).

-

(ii)

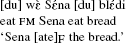

In the case of the so-called Predicate Doubling illustrated in (iii) with Gungbe (Kwa; see Aboh 2004), the focus marker wὲ is to the right of the preposed verb (see below for similar examples).

-

(iii)

-

(i)

The constraint Align-Foc-ι-R is not eliminated from the competition, but it is now low ranking. Its effect cannot be felt anymore, as it is dominated by Align-Foc-ι-L.

In Truckenbrodt (1995), a different analysis was provided for the same data. One constraint required that a focus have the highest prominence in its domain, and another demanded alignment between the head of a prosodic phrase and its right edge. In other words, the focus was not directly aligned to a prosodic edge, but rather it was the need to be prominent which forced alignment, as was explained above with Italian, French and Hungarian.

Only a stronger focus on the hierarchy given in (6) can have the effect of lifting this restriction.

Dutch and English behaved like German in the Anima experiment.

Depending on the location of the accent, it can stand just for itself or project to a larger syntactic constituent (see Selkirk 1995; Rochemont 1986; Uhmann 1991; Cinque 1993 and many others). This property has been called ‘integration’ by Fuchs (1976) and Jacobs (1993), and ‘subordination’ by Wagner (2005) who proposes a different explanation of this property than the one shown in this section. The rules underlying the faculty of an accent to project to a larger constituent have been discussed a number of times in the literature. I refer the reader to Gussenhoven (1992), Truckenbrodt (2007) and Féry (2011) for OT analyses.

It should be noted that this subject/non-subject asymmetry was already observed for German, Italian, French and Chicheŵa above, where it was shown to correlate with canonical vs. non-canonical word order.

The language’s name is sometimes written Fɔn or Fongbe in the literature.

From Fiedler et al. (2010:237): “The class of morphological focus markers is not homogeneous but comprises at least the following list of formal elements, many of which also occur independently in non-focus contexts: (i) invariant information-structural particles; (ii) particles agreeing in gender with the focused NP/DP; (iii) copulas; and (iv) nominal affixes.”

Reineke (2007) shows for another Gur language, Byali, that an ex-situ focus strategy has an identificational function for non-subjects. An informational role is expressed by in-situ focus (see É.Kiss 1998 for the distinction between informational and identificational). A subject in Byali is always focused by means of an ex-situ strategy. Like in Ditammari, the focus constituent is followed by a focus marker in all cases.

Reineke (2006b:163) claims that both Ditammari and Byali use syntactic, morphological and phonological reflexes of focus.

In Fiedler et al.’s account the position of the focus is motivated in the syntax: a focus targets the position immediately following the verb.

In particular, the absence of a prosodic boundary after a focus constituent in lab speech with given word orders cannot be used to falsify the FA approach, which is designed for spontaneous or semi-spontaneous speech.

Alignment can be compared to the notion of ‘given before new’ from Clark and Haviland (1977), also proposed by Chafe (1976). Alignment replaces the uni-directionality intrinsic to this principle and replaces it with a more flexible property, namely the need to be at an edge of a prosodic constituent.

We saw in (39) that Truckenbrodt requires ‘highest prominence’ for focus, but this does not refer to the highest F0 value.

References

Aboh, Enoch O. 2004. The morphosyntax of complement-head sequences. Clause structure and word order patterns in Kwa: Oxford studies in comparative syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aboh, Enoch O. 2010. Information structuring begins with the numeration. Iberia: An International Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 2: 12–42.

Arnhold, Anja. To appear. Prosodic structure and focus realization in West Greenlandic. In Prosodic typology. The phonology of intonation and phrasing, Vol. 2. ed. Sun-Ah Jun. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aronson, Howard I. 1982/1990. Georgian: A reading grammar. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers, Inc.

Astruc, Maria Lluisa. 2005. The intonation of extra-sentential elements in Catalan and English, PhD diss., University of Cambridge.

Balogh, Kata. 2009. Theme with variations: A context-based analysis of focus, Unpublished PhD diss., University of Amsterdam.

Beckman, Mary E. and Janet B. Pierrehumbert. 1986. Intonational structure in Japanese and English. Phonology Yearbook 3: 255–309.

Beyssade, Claire, Barbara Hemforth, Jean-Marie Marandin, and Cristel Portes. 2009. Prosodic markings of information focus in French. In Proceedings of the conference interface discours & prosodie, Paris, France, eds. Hi-Yon Yoo and Elisabeth Delais-Roussarie, 109–122.

Boeder, Winfried. 2005. The South Caucasian languages. Lingua 115: 5–89.

Bródy, Michael. 1990. Remarks on the order of elements in the Hungarian focus field. In Approaches to Hungarian, Vol. 3: Structures and arguments, eds. István Kenesei and Cs. Pléh, 95–121. Szeged: JATE.

Büring, Daniel. 2010. Towards a typology of focus realization. In Information structure. Theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 177–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chafe, William L. 1976. Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In Subject and topic, ed. C. N. Li, 25–55. New York: Academic Press.

Chen, Matthew Y. 1987. The syntax of Xiamen tone sandhi. Phonology Yearbook 4: 109–150.

Cheng, Lisa and Laura Downing. 2011. Mapping phonology to syntax: evidence from two wh-in-situ languages. Handout. GLOW 34. Vienna.

Chomsky, Noam. 1971. Deep structure, surface structure, and semantic interpretation. In Semantics: An interdisciplinary reader in philosophy, linguistics and psychology, eds. Danny D. Steinberg and Leon A. Jakobovits, 183–216. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1993. A null theory of phrase and compound stress. Linguistic Inquiry 24(2): 239–297.

Clark, Herbert H. and Susan E. Haviland. 1977. Comprehension and the given-new contract. In Discourse processes: Advances in research and theory, ed. R. O. Freedle. Vol. 1 of Discourse production and comprehension, 1–40. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Clesh-Darbon, Anne Rebuschi and Annie Rialland. 1999. Are there cleft sentences in French? In The grammar of focus, eds. Georges Rebuschi and Laurice Tuller, 83–118. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Cozier, Franz K. 2006. The co-occurrence of predicate clefting and wh-questions in Trinidad dialectal English. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 24: 655–688.

De Cat, Cécile. 2007. French dislocation without movement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25(3): 485–534.

Downing, Laura J. and Bernd Pompino-Marschall. 2013. The focus prosody of Chichewa and the Stress-Focus constraint: A response to Samek-Lodovici. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31(3). doi:10.1007/s11049-013-9192-x.

Downing, Laura J., Al Mtenje, and Bernd Pompino-Marschall. 2004. Prosody and information structure in Chicheŵa. In ZAS papers in linguistics 37. Papers in phonetics and phonology, eds. Susanne Fuchs and Silke Hamann, 167–186.

É.Kiss, Katalin, 1987. Configurationality in grammar. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

É.Kiss, Katalin, 1998. Identificational focus versus information focus. Language 74(2): 245–273.

É.Kiss, Katalin, 2010. An adjunction analysis of quantifiers and adverbials in the Hungarian sentence. Lingua 120: 506–526.

Elordieta, Gorka. 2007. Constraints on intonational prominence of focalized constituents. In Topic and focus: Cross-linguistic perspectives on meaning and intonation, eds. Chungmin L. L. Lee, Matthew Gordon, and Daniel Büring. Berlin: Springer.

Elordieta, Gorka, Inaki Gaminde, Inma Heráez, Jasone Salaberria, and Igor Martín de Vidales. 1999. Another step in the modeling of Basque intonation: Bermeo. In Text, speech and dialogue, eds. V. Matousek, P. Mautner, J. Ocelíková, and P. Soika, 361–364. Berlin: Springer.

Fanselow, Gisbert and Caroline Féry. 2006. Prosodic and morphosyntactic aspects of discontinuous noun phrases: A comparative perspective. Ms., Universität Potsdam.

Feldhausen, Ingo. 2010. Sentential form and prosodic structure of Catalan. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Féry, Caroline. 2011. German sentence accents and embedded prosodic phrases. Lingua 121: 1906–1922.

Féry, Caroline. To appear. Final compression in French as a phrasal phenomenon. Ms., Frankfurt.

Féry, Caroline, Robin Hörnig, and Serge Pahaut. 2010. Phrasing in French and German: An experiment with semi-spontaneous speech. In Intonational phrasing at the interfaces: Cross-linguistic and bilingual studies in Romance and Germanic, eds. Christoph Gabriel and Conxita Lleó, 11–41. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Féry, Caroline and Vieri Samek-Lodovici. 2006. Focus projection and prosodic prominence in nested foci. Language 82(1): 131–150.

Fiedler, Ines, Katharina Hartmann, Brigitte Reineke, Anne Schwarz, and Malte Zimmermann. 2010. Subject focus in West African languages. In Information structure from different perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 234–257. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frascarelli, Mara. 2000. The syntax-phonology interface in focus and topic constructions in Italian. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Frota, Sónia. 2000. Prosody and focus in European Portuguese, New York: Garland.

Fuchs, Anna. 1976. ‘Normaler’ und ‘kontrastiver’ Akzent. Lingua 38: 293–312.

Green, Melanie and Philip Jaggar. 2003. Ex-situ and in-situ focus in Hausa: Syntax, semantics and discourse. In Research in Afroasiatic grammar II, ed. J. Lecarme. Vol. 241 of CILT, 187–213. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1997. Projection, heads and optimality. Linguistic Inquiry 28(3): 373–422.

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 1983. Focus, mode and the nucleus. Journal of Linguistics 19: 377–417.

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 1992. Sentence accents and argument structure. In Thematic structure. Its role in grammar, ed. Iggy Roca, 79–106. Berlin: Foris.

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2004. The phonology of tone and intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2008. Notions and subnotions in information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55: 381–395.

Hamlaoui, Fatima. 2009a. Le focus à l’interface de la syntaxe et de la phonologie: le cas du français dans une perspective typologique, Unpublished Thèse de Doctorat, Université Paris III.

Hamlaoui, Fatima. 2009b. Focus, contrast and the syntax-phonology interface: The case of French cleft sentences. In Current issues in unity and diversity of languages: Collection of the papers selected from the 18th international congress of linguistics (2008). Seoul: The Linguistic Society of Korea.

Harris, Alice. 2000. Word order harmonies and word order change in Georgian. In Stability, variation and change of word-order patterns over time, eds. R. Sornicola, E. Poppe, and A. Shisha-Halevy, 133–163. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hartmann, Katharina and Malte Zimmermann. 2007. In place – out of place: Focus in Hausa. In On information structure: Meaning and form, eds. Kerstin Schwabe and Susanne Winkler, 365–403. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hayes, Bruce. 1989. The prosodic hierarchy in meter. In Rhythm and meter, eds. Paul Kiparsky and Gilbert Youngmans, 201–260. Orlando: Academic Press.

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory: Principles and case studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayes, Bruce and Aditi Lahiri. 1991. Bengali intonational phonology. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 9: 47–99.

Horváth, Julia. 1986. Focus in the theory of grammar and the syntax of Hungarian. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Horváth, Julia. 2007. Separating “focus movement” from focus. In Phrasal and clausal architecture. Syntactic derivation and interpretation. In honor of Joseph E. Emonds, eds. S. Karimi, V. Samiian, and W. K. Wilkins. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hualde, Juan, Gorka Elordieta, Iñaki Gaminde, and Rajka Smiljanić. 2002. From pitch-accent to stress-accent in Basque. In Laboratory phonology 7, eds. Carlos Gussenhoven and Natasha Warner, 547–584. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hunyadi, László. 2002. Hungarian sentence prosody and universal grammar. Tübingen: Peter Lang.

Hyman, Larry M. and Maria Polinsky. 2010. Focus in Aghem. In Information structure from different perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 206–233. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2003. Intonation and interface conditions, PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2007. Major phrase, focus intonation and multiple spell-out (MaP, FI, MSO). The Linguistic Review 24: 137–167.

Itô, Junko and Armin Mester. 1994. Reflections on CodaCond and alignment. In Phonology at Santa Cruz 3, eds. J. Merchant, J. Padgett, and R. Walker, 27–46. Santa Cruz: University of California.

Itô, Junko and Armin Mester. 2009. The extended prosodic word. In Phonological domains: Universals and deviations, eds. Janet Grijzenhout and Baris Kabak, Interface explorations series, 135–194. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Itô, Junko and Armin Mester. 2012. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In Prosody matters: Essays in honor of Elisabeth Selkirk, eds. T. Borowsky, S. Kawahara, T. Shinya, and M. Sugahara, 280–303. London: Equinox Publishers.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1993. Integration. In Wortstellung und Informationsstruktur, ed. Marga Reis. Vol. 306 of Linguistische Arbeiten. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Jacobs, Joachim. 2001. The dimensions of topic-comment. Linguistics 39: 641–681.

Kanerva, Jonni M. 1990. Focusing on phonological phrases in Chicheŵa. In Phonology-syntax-interface, eds. Sharon Inkelas and Draga Zec, 145–161. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Keane, Elinor. (to appear). Tamil. In Prosodic typology. The phonology of intonation and phrasing, Vol. 2. ed. Sun-Ah Jun. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kentner, Gerrit and Caroline Féry. 2013. A new approach to prosodic grouping. The Linguistic Review 30: 3.

Khan, Sameer ud Dowla. 2008. Intonational phonology and focus prosody of Bengali, PhD diss., University of California at Los Angeles.

Khan, Sameer ud Dowla. 2011. The intonational phonology of Bangladeshi Standard Bengali. Ms., Brown University.

Koch, Karsten. 2008a. Focus projection in Nɬeʔkepmxcin (Thompson River Salish). In Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, eds. C. B. Chang and H. J. Haynie, 348–356. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Koch, Karsten. 2008b. Intonation and focus in Nɬeʔkepmxcin (Thompson River Salish), PhD diss., University of British Columbia.

Kratzer, Angelika and Elisabeth Selkirk. 2007. Phase theory and prosodic spellout: The case of verbs. The Linguistic Review 24: 93–135. Special issue on prosodic phrasing and tunes.

Krifka, Manfred. 1999. Additive particles under stress. In Proceedings of SALT 8, 111–128. Cornell: CLC Publications.

Krifka, Manfred. 2008. Basic notions of information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55: 243–276.

Kroeber, Paul. 1997. Relativization in Thompson Salish. Anthropological Linguistics 39: 376–422.

Ladd, D. Robert. 1980. The structure of intonational meaning: Evidence from English. Bloomington: Distributed (1980) by the Indiana University Linguistic Club.

Ladd, D. Robert. 2008. Intonational phonology, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lenerz, Jürgen. 1977. Zur Abfolge nominaler Satzglieder im Deutschen. Narr. Tübingen.

Liberman, Mark and Alan Prince. 1977. On stress and linguistic rhythm. Linguistic Inquiry 8: 249–336.

López, Luis. 2009. Ranking the linear correspondence axiom. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 239–276.

McCarthy, John J. 2003. OT constraints are categorical. Phonology 20: 75–138.

McCarthy, John J. and Alan Prince. 1993. Generalized alignment. In Yearbook of morphology 1993, eds. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle, 79–153. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

McGinnis, Martha. 1997a. Case and locality in L-syntax: Evidence from Georgian. In MITWPL 32: The UPenn/MIT roundtable on argument structure and aspect, ed. Heidi Harley, MIT working papers in linguistics, 139–158. Cambridge.

McGinnis, Martha. 1997b. Reflexive external arguments and lethal ambiguity. In Proceedings of WCCFL 16, eds. E. Curtis, J. Lyle, and G. Webster, 303–317. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Nash, Léa. 1995. Portée argumentale et marquage casuel dans les langues SOV et dans les langues ergatives: l’exemple du géorgien, PhD diss., Université de Paris VIII.

Nespor, Marina and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic phonology. Dordrecht: Foris.

Patil, Umesh, Anja Gollard, Gerrit Kentner, Frank Kügler, Caroline Féry, and Shravan Vasishth. 2007. Focus, word order and intonation in Hindi. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 1: 53–70.

Piou, Nanie. 1982. Le clivage du prédicat. In Syntaxe de l’haïten, ed. C. Lefebvre, 122–152. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers.

Prince, Alan and Paul Smolensky. 1993. Optimality theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar. Ms., Rutgers University, New Brunswick, & University of Colorado, Boulder.

Reineke, Brigitte. 2006a. Focus et topique en tant que deux phénomènes pragmatiques dans les langues Oti-Volta orientales. Cahïers Voltaïques/Gur Papers 7: 100–111.

Reineke, Brigitte. 2006b. Verb- und Prädikationsfokus im Ditammari und Byali. In Zwischen Bantu und Burkina. Festschrift für Gudrun Miehe zum 65. Geburtstag, eds. K. Winkelmann and D. Ibriszimow, 163–180. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Reineke, Brigitte. 2007. Identificational operation as focus strategy in Byali. In Focus strategies in African languages, eds. Enoch O. Aboh, Katharina Hartmann, and Malte Zimmermann, 223–240. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1981. Pragmatics and linguistics: An analysis of sentence topics. Philosophica 27: 53–94.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1995. Interface strategies, Ms., OTS/University of Utrecht.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Robins, R. H. and Natalie Waterson. 1952. Notes on the phonetics of the Georgian word. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 14(1): 55–72.

Rochemont, Michael. 1986. Focus in generative grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Associations with focus, PhD Diss., Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116.

Samek-Lodovici, Vieri. 2005. Prosody-syntax interaction in the expression of focus. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 23: 637–755.

Samek-Lodovici, Vieri. 2006. When right dislocation meets the left-periphery: A unified analysis of Italian non-final focus. Lingua 116: 836–873.

Schuh, Russell G. 2005. Yobe State, Nigeria, as a linguistic area. Paper presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Schwarz, Anne and Ines Fiedler. 2007. Narrative focus strategies in Gur and Kwa. In Focus strategies in African languages, eds. Enoch O. Aboh, Katharina Hartmann, and Malte Zimmermann, 267–286. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Schwarzschild, Roger. 1999. GIVENness, AvoidF and other constraints on the placement of accent. Natural Language Semantics 7: 141–177.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1984. Phonology and syntax. The relation between sound and structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1986. On derived domains in sentence phonology. Phonology Yearbook 3: 371–405.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1995. Sentence prosody: Intonation, stress and phrasing. In The handbook of phonological theory, ed. John Goldsmith, 550–569. Oxford: Blackwell.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 2000. The interaction of constraints on prosodic phrasing. In Prosody: Theory and experiment, ed. Merle Horne, 231–261. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 2009. On clause and intonational phrase in Japanese: The syntactic grounding of prosodic constituent structure. Gengo Kenkyu 136.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. O. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface In The handbook of phonological theory, 2nd edn., eds. John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle, and Alan Yu.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. O. and Tong Shen. 1990. Prosodic domains in Shanghai Chinese. In The phonology-syntax-interface, eds. Sharon Inkelas and Draga Zec, 313–337. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Skopeteas, Stavros and Gisbert Fanselow. 2008. Focus types and argument asymmetries: A cross-linguistic study in language production. In Contrastive information structure analysis, ed. Breul Carsten. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Skopeteas, Stavros and Gisbert Fanselow. 2010a. Effects of givenness and constraints on free word order. In Information structure from different perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmerman and Caroline Féry, 307–331. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skopeteas, Stavros and Gisbert Fanselow. 2010b. Focus in Georgian and the expression of contrast. Lingua 120: 1370–1391.

Skopeteas, Stavros and Caroline Féry. 2010c. Effect of narrow focus on tonal realization in Georgian. In Proceedings of speech prosody 2010 in Chicago.

Skopeteas, Stavros, Ines Fiedler, Sam Hellmuth, Anne Schwarz, Ruben Stoel, Gisbert Fanselow, Caroline Féry, and Manfred Krifka. 2006. Questionnaire on information structure (ISIS Vol. 4). Potsdam: Universitätsverlag. Available online. http://www.sfb632.uni-potsdam.de/en/quis-en/quis-materials-en.html.

Swerts, Marc, Emiel Krahmer, and Cinzia Avesani. 2002. Prosodic marking of information status in Dutch and Italian: A comparative analysis. Journal of Phonetics 30: 629–654.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1981. The semantics of topic-focus articulation. In Formal methods in the study of language, eds. Jeroen Groenendijk, Theo Janssen, and Martin Stokhof. Amsterdam: Mathematisch Centrum.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1994. All quantifiers are not equal: The case of focus. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 42: 171–187.

Szendrői, Kriszta. 2003. A stress-based approach to the syntax of Hungarian focus. The Linguistic Review 20: 37–78.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Phonological phrases: Their relation to syntax, focus and prominence, Unpublished PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, Mass.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1999. On the relation between syntactic phrases and phonological phrases. Linguistic Inquiry 30(2): 219–255.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2005. A short report on intonation phrase boundaries in German. Linguistische Berichte 203: 273–296.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2007. The syntax-phonology interface. In The Cambridge handbook of phonology, ed. Paul de Lacy, 435–456. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uhmann, Susanne. 1991. Fokusphonologie. Eine Analyse deutscher Intonationskonturen im Rahmen der nicht-linearen Phonologie. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Vallduví, Enric. 1992. The informational component. New York: Garland.

Vallduví, Enric and Maria Vilkuna. 1998. On rheme and contrast. In The limits of syntax, eds. Peter Culicover and Louise McNally, 161–184. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Varga, László. 2002. Intonation and stress: evidence from Hungarian. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Vicenik, Chad and Sun-Ah Jun. to appear. An autosegmental-metrical analysis of Georgian intonation. In Prosodic typology. The phonology of intonation and phrasing, Vol. 2. ed. Sun-Ah Jun. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Villalba, Xavier. 2000. The syntax of sentence periphery, PhD diss., Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bella-Terra.

Vogel, Irene and István Kenesei. 1987. The interface between phonology and other components of grammar: The case of Hungarian. Phonology Yearbook 4: 243–263.

Wagner, Michael. 2005. Prosody and recursion, PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Wagner, Michael. 2010. Prosody and recursion in coordinate structures and beyond. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 28: 183–237.

Zimmermann, Malte. 2008. Contrastive focus and emphasis. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55: 347–360.

Zubizaretta, Maria Luisa. 1998. Prosody, focus and word order. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

This paper was first presented at the XXth Colloquium on Generative Grammar in Barcelona in March 2010, and I would like to thank the organizers, Josep Quer and Pilar Prieto, for giving me the opportunity to present my views on focus there. People who have had an influence on the content of this paper are numerous. Among them are Anja Arnhold, Kirsten Brock, Gisbert Fanselow, Fatima Hamlaoui, Shin Ishihara, Gerrit Kentner, Frank Kügler, Sara Myrberg, Fabian Schubö, Lisa Selkirk, Stavros Skopeteas and Malte Zimmermann. But this list is far from being exhaustive. I would also like to thank three reviewers for NLLT, two anonymous ones and Hubert Truckenbrodt, for generous and helpful comments on a first version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Féry, C. Focus as prosodic alignment. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 31, 683–734 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9195-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9195-7