Abstract

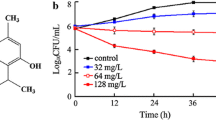

Invasive candidiasis is caused mainly by Candida albicans, but other Candida species have increasing etiologies. These species show different virulence and susceptibility levels to antifungal drugs. The aims of this study were to evaluate the usefulness of the non-conventional model Caenorhabditis elegans to assess the in vivo virulence of seven different Candida species and to compare the virulence in vivo with the in vitro production of proteinases and phospholipases, hemolytic activity and biofilm development capacity. One culture collection strain of each of seven Candida species (C. albicans, Candida dubliniensis, Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, Candida metapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis and Candida parapsilosis) was studied. A double mutant C. elegans AU37 strain (glp-4;sek-1) was infected with Candida by ingestion, and the analysis of nematode survival was performed in liquid medium every 24 h until 120 h. Candida establishes a persistent lethal infection in the C. elegans intestinal tract. C. albicans and C. krusei were the most pathogenic species, whereas C. dubliniensis infection showed the lowest mortality. C. albicans was the only species with phospholipase activity, was the greatest producer of aspartyl proteinase and had a higher hemolytic activity. C. albicans and C. krusei caused higher mortality than the rest of the Candida species studied in the C. elegans model of candidiasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC. Invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1445–56.

Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4:119–28.

Arvanitis M, Glavis-Bloom J, Mylonakis E. Invertebrate models of fungal infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1378–83.

Muhammed M, Arvanitis M, Mylonakis E. Whole animal HTS of small molecules for antifungal compounds. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2016;11:177–84.

Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E. Candida albicans infection of Caenorhabditis elegans induces antifungal immune defenses. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002074.

Tan X, Fuchs BB, Wang Y, et al. The role of Candida albicans SPT20 in filamentation, biofilm formation and pathogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94468.

Amorim-Vaz S, Delarze E, Ischer F, et al. Examining the virulence of Candida albicans transcription factor mutants using Galleria mellonella and mouse infection models. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:367.

Glavis-Bloom J, Muhammed M, Mylonakis E. Of model hosts and man: using Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster and Galleria mellonella as model hosts for infectious disease research. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;710:11–7.

Scorzoni L, de Lucas MP, Mesa-Arango AC, et al. Antifungal efficacy during Candida krusei infection in non-conventional models correlates with the yeast in vitro susceptibility profile. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60047.

Gago S, García-Rodas R, Cuesta I, et al. Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis virulence in the non-conventional host Galleria mellonella. Virulence. 2014;5:278–85.

Souza AC, Fuchs BB, Pinhati HM, et al. Candida parapsilosis resistance to fluconazole: molecular mechanisms and in vivo impact in infected Galleria mellonella larvae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:6581–7.

Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. 2006:1–11. doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1.

Breger J, Fuchs BB, Aperis G, et al. Antifungal chemical compounds identified using a C. elegans pathogenicity assay. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e18.

Cassone A, De Bernardis F, Mondello F, et al. Evidence for a correlation between proteinase secretion and vulvovaginal candidosis. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:777–83.

Polak A. Virulence of Candida albicans mutants. Mycoses. 1992;35:9–16.

Price MF, Wilkinson ID, Gentry LO. Plate method for detection of phospholipase activity in Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1982;20:7–14.

Luo G, Samaranayake LP, Yau JY. Candida species exhibit differential in vitro hemolytic activities. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2971–4.

Manns JM, Mosser DM, Buckley HR. Production of a hemolytic factor by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5154–6.

Ramage G, Vandewalle K, Wickes BL, López-Ribot JL. Characteristics of biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2001;18:163–70.

Tortorano AM, Prigitano A, Biraghi E, Viviani MA. FIMUA-ECMM Candidaemia Study Group. The European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) survey of candidaemia in Italy: in vitro susceptibility of 375 Candida albicans isolates and biofilm production. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:777–9.

Pemán J, Cantón E, Quindós G, et al. Epidemiology, species distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of fungaemia in a Spanish multicentre prospective survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1181–7.

Quindós G. Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31:42–8.

Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:327–35.

Desalermos A, Fuchs BB, Mylonakis E. Selecting an invertebrate model host for the study of fungal pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002451.

Arendrup M, Horn T, Frimodt-Møller N. In vivo pathogenicity of eight medically relevant Candida species in an animal model. Infection. 2002;30:286–91.

Pukkila-Worley R, Peleg AY, Tampakakis E, Mylonakis E. Candida albicans hyphal formation and virulence assessed using a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:1750–8.

Treviño-Rangel RDJ, Rodríguez-Sánchez IP, Elizondo-Zertuche M, et al. Evaluation of in vivo pathogenicity of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis with different enzymatic profiles in a murine model of disseminated candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2014;52:240–5.

Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM. Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:3–9.

Lionakis MS. Drosophila and Galleria insect model hosts: new tools for the study of fungal virulence, pharmacology and immunology. Virulence. 2011;2:521–7.

West L, Lowman DW, Mora-Montes HM, et al. Differential virulence of Candida glabrata glycosylation mutants. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22006–18.

Jacobsen ID, Brunke S, Seider K, et al. Candida glabrata persistence in mice does not depend on host immunosuppression and is unaffected by fungal amino acid auxotrophy. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1066–77.

Junqueira JC, Fuchs BB, Muhammed M, et al. Oral Candida albicans isolates from HIV-positive individuals have similar in vitro biofilm-forming ability and pathogenicity as invasive Candida isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:247.

Asmundsdóttir LR, Erlendsdóttir H, Agnarsson BA, Gottfredsson M. The importance of strain variation in virulence of Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans: results of a blinded histopathological study of invasive candidiasis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:576–85.

Mariné M, Pastor FJ, Sahand IH, et al. Paradoxical growth of Candida dubliniensis does not preclude in vivo response to echinocandin therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5297–9.

Koga-Ito CY, Komiyama EY, Martins CA, et al. Experimental systemic virulence of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates in comparison with Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei. Mycoses. 2011;54:e278–85.

Sullivan DJ, Moran GP. Differential virulence of Candida albicans and C. dubliniensis: a role for Tor1 kinase? Virulence. 2011;2:77–81.

Shin JH, Kee SJ, Shin MG, et al. Biofilm production by isolates of Candida species recovered from nonneutropenic patients: comparison of bloodstream isolates with isolates from other sources. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1244–8.

Dagdeviren M, Cerikcioglu N, Karavus M. Acid proteinase, phospholipase and adherence properties of Candida parapsilosis strains isolated from clinical specimens of hospitalised patients. Mycoses. 2005;48:321–6.

Stokes C, Moran GP, Spiering MJ, et al. Lower filamentation rates of Candida dubliniensis contribute to its lower virulence in comparison with Candida albicans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44:920–31.

Moran GP, Coleman DC, Sullivan DJ. Candida albicans versus Candida dubliniensis: why is C. albicans more pathogenic? Int J Microbiol. 2012;2012:205921.

Marcos-Arias C, Eraso E, Madariaga L, et al. Phospholipase and proteinase activities of Candida isolates from denture wearers. Mycoses. 2011;54:e10–6.

Tobouti PL, Casaroto AR, de Almeida RS, et al. Expression of secreted aspartyl proteinases in an experimental model of Candida albicans-associated denture stomatitis. J Prosthodont. 2016;25:127–34.

Ishii M, Matsumoto Y, Sekimizu K. Usefulness of silkworm as a host animal for understanding pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. Drug Discov Ther. 2016;10:9–13.

Hanaoka N, Takano Y, Shibuya K, et al. Identification of the putative protein phosphatase gene PTC1 as a virulence-related gene using a silkworm model of Candida albicans infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1640–8.

Nayak AP, Green BJ, Beezhold DH. Fungal hemolysins. Med Mycol. 2013;51:1–16.

Chen YZ, Yang YL, Chu WL, et al. Zebrafish egg infection model for studying Candida albicans adhesion factors. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0143048.

Villar-Vidal M, Marcos-Arias C, Eraso E, Quindós G. Variation in biofilm formation among blood and oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2011;29:660–5.

Williams C, Ramage G. Fungal biofilms in human disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;831:11–27.

Nash EE, Peters BM, Lilly EA, et al. A murine model of Candida glabrata vaginitis shows no evidence of an inflammatory immunopathogenic response. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147969.

Gulati M, Nobile CJ. Candida albicans biofilms: development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 2016;18:310–21.

Frenkel M, Mandelblat M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, et al. Pathogenicity of Candida albicans isolates from bloodstream and mucosal candidiasis assessed in mice and Galleria mellonella. J Mycol Med. 2016;26:1–8.

Borghi E, Romagnoli S, Fuchs BB, et al. Correlation between Candida albicans biofilm formation and invasion of the invertebrate host Galleria mellonella. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:163–73.

Perdoni F, Falleni M, Tosi D, et al. A histological procedure to study fungal infection in the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Eur J Histochem. 2014;58:2428.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Consejería de Educación, Universidades e Investigación [GIC 15/78 IT-990-16] and the Departamento de Industria, Comercio y Turismo [S-PR11UN003, S-PE13UN121] of Gobierno Vasco-Eusko Jaurlaritza, the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria [FIS PI11/00203], the Fundación ONCE “Oportunidad al Talento” and the Fondo Social Europeo [to C.M-A.], and the Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea [UFI 11/25 and scholarship from the ZabaldUz program to I.D-l-P.]. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

In the past 5 years, Elena Eraso has received grant support from Astellas Pharma and Pfizer SLU. Guillermo Quindós has received grant support from Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer SLU, Scynexis and Merck Sharp and Dohme. In addition, he has been an advisor/consultant to Merck Sharp and Dohme and has been paid for talks on behalf of Abbvie, Astellas Pharma, Esteve Hospital, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer SLU and Scynexis. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed above.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ortega-Riveros, M., De-la-Pinta, I., Marcos-Arias, C. et al. Usefulness of the Non-conventional Caenorhabditis elegans Model to Assess Candida Virulence. Mycopathologia 182, 785–795 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-017-0142-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-017-0142-8