Abstract

Drawing on emotional intensity theory (EIT: Brehm in Personality and Social Psychology Review 3:2–22, 1999; Brehm and Miron in Motivation and Emotion 30:13–30, 2006), this experiment (N = 104) shows how the manipulated risk of ending a romantic relationship influences the intensity of romantic affect and commitment. As predicted by EIT, the intensity of both romantic feelings varied as a cubic function of increasing levels of manipulated risk of relationship breakup (risk not mentioned vs. low vs. moderate vs. high). Data additionally showed that the effects of manipulated risk on romantic commitment were fully mediated by feelings of romantic affect. These findings complement and extend prior research on romantic feelings (Miron et al. in Motivation and Emotion 33:261–276, 2009; Miron et al. in Journal of Relationships Research 3:67–80, 2012) (a) by highlighting the barrier-like properties of manipulated risk of relationship breakup and its causal role in shaping romantic feelings, and (b) by suggesting that any obstacle can systematically control—thus, either reduce or enhance—the intensity of romantic feelings to the extent that such obstacles are perceived as ‘risky’ for the fate of the relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We did not consider more recent work by Miron et al. (2012) for sample size estimation, because two of the three studies reported by Miron and her colleagues were correlational in nature, whereas the third study—a true experiment—was designed to evaluate a more articulated research question and, also, did not find any main effect of the experimental manipulation on romantic affect.

In the original Italian wording of this item, the expression “From a pure emotional point of view, I feel completely motivated towards my romantic partner” [“Da un punto di vista puramente emotivo, mi sento completamente motivato nei confronti del mio partner”] conveys a strong sense of emotional involvement, that corresponds to a strong feeling of leaning towards the partner and feeling good with her/him, and also to a manifest sense of comfort and attraction towards the partner/relationship. This fact is reflected in the high value of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the three items measuring romantic affect (α = 0.93).

A preliminary one-sample t-test revealed that the mean ratings of romantic affect in the control condition (M = 10.81, SD = 1.28; scale range 0–12.50 cm) were, on the average, significantly higher than the scale neutral midpoint (= 6.25), t (25) = 18.18, p < .001. This result may be taken to suggest that, at the beginning of the study, a relatively high degree of romantic affect was successfully induced in participants (see ‘Participants, design and procedure’ section above; cf. Brehm et al. 2009; Miron et al. 2007, 2008). As suggested by emotional intensity theory, in order to deter an affective state, that state must first be present with a certain degree of intensity (Brehm 1999). An analogous one-sample t-test run with respect to participants’ commitment ratings in the control condition (M = 10.91, SD = 1.32; scale range 0–12.50 cm) revealed that relationship commitment was significantly higher, on the average, than the corresponding scale neutral midpoint (= 6.25), t (25) = 18.01, p < .001. Thus, also a certain degree of romantic commitment was presumably present before the risk (i.e., deterrence) manipulation.

Importantly, a further one-way ANOVA indicated that, as expected, the mean number of discussions and/or minor quarrels that participants reported to have typically had, per week, with their romantic partner (M total = 1.35, SD total = 1.54) did not differ among low (M = 1.29, SD = 1.24) vs. moderate (M = 1.54, SD = 2.19) vs. high (M = 1.22, SD = 1.01) risk conditions, F (2, 75) = 0.30, p = 0.743. It was therefore the false feedback in itself—not the actual number of recalled troublesome exchanges between partners—that systematically deterred romantic affect. In the control condition, of course, no reference to disputes between partners was made, nor participants were asked to recall such potentially stressful episodes.

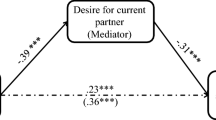

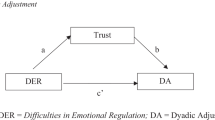

We conducted also a traditional Baron and Kenny (1986) mediation analysis, in which (1) the risk of breakup predicted both the intensity of romantic commitment (β = 0.27, t = 2.841, p = .005) and (2) of romantic affect (β = 0.34, t = 3.594, p = .001); (3) the intensity of romantic affect predicted the intensity of commitment (β = 0.85, t = 16.161, p < .001); and, finally, (4) the risk of breakup no longer predicted the intensity of commitment when romantic affect was entered into the equation (β = − 0.02, t = − 0.271, p = 0.79)—this signaling complete mediation. The indirect path was significant at the Sobel (1982) test (test statistic = 3.52, Se = 0.15, p < .001).

Technically, we cannot attribute, univocally, the observed effects to the influence of the manipulation at step 1 (perceived likelihood of general relationship failure after two years), instead to the influence of the manipulation at step 3 (perceived likelihood of personal relationship failure after two years), or to a combination of both. However, we considered the complete three-step procedure necessary to guarantee the credibility of the personalized feedback information to be given at step 3. Each of the two steps (step 1 and 3), if implemented alone, could have not been sufficient to effectively manipulate the independent variable. Further, both steps 1 and 3 were intended to operationalize the same theoretical construct in different but converging ways. Thus, both steps shared the same operative goal—inducing in participants a sense of being at risk.

References

Ach, N. (1910). Über den Willensakt und das Temperament [About the act of will and temperament]. Leipzig: Quelle und Meyer.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Brassard, A., Lussier, Y., & Shaver, P. R. (2009). Attachment, perceived conflict, and couple satisfaction: Test of a mediational dyadic model. Family Relations, 58, 634–646. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00580.x.

Brehm, J. W. (1975). Research on motivational suppression [Grant Proposal]. Lawrence: University of Kansas.

Brehm, J. W. (1999). The intensity of emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 2–22. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0301_1.

Brehm, J. W., & Brummett, B. H. (1998). The emotional control of behavior. In M. Kofta, G. Weary, & G. Sedek (Eds.), Personal control in action (pp. 133–154). New York: Plenum.

Brehm, J. W., Brummett, B. H., & Harvey, L. (1999). Paradoxical sadness. Motivation and Emotion, 23, 31–44. doi:10.1023/A:1021379317763.

Brehm, J. W., & Miron, A. M. (2006). Can the simultaneous experience of opposing emotions really occur? Motivation and Emotion, 30, 13–30. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9007-z.

Brehm, J. W., Miron, A. M., & Miller, K. (2009). Affect as a motivational state. Cognition and Emotion, 23, 1069–1089. doi:10.1080/02699930802323642.

Brehm, J. W., & Self, E. A. (1989). The intensity of motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 109–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.000545.

Brehm, J. W., Wright, R. A., Solomon, S., Silka, L., & Greenberg, J. (1983). Perceived difficulty, energization, and the magnitude of goal valence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 21–48. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(83)90003-3.

Brummett, B. H. (1996). The intensity of anger. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas.

Brunell, A. B., Pilkington, C. J., & Webster, G. D. (2007). Perceptions of risk in intimacy in dating couples: Conversation and relationship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 92–119. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.1.92.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J.A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510–531. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J. (1990). Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist, 45,1304–1312. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.12.1304.

Dill, J. (1997). Paradoxical anger: Investigations into the emotional and physiological predictions of Brehm’s theory of emotional intensity. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri, Columbia.

Driscoll, R. (2014). Commentary and rejoinder on Sinclair, Hood, and Wright (2014): Romeo and Juliet through a narrow window. Social Psychology, 45, 312–314. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000203.

Driscoll, R., Davis, K. E., & Lipetz, M. E. (1972). Parental interference and romantic love: The Romeo and Juliet effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 1–10. doi:10.1037/h0033373.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146.

Felmlee, D. (2001). No couple is an island: A social network perspective on dyadic stability. Social Forces, 79, 1259–1257. doi:10.1353/sof.2001.0039.

Felmlee, D., Sprecher, S., & Bassin, E. (1990). The dissolution of intimate relationships: A hazard model. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53, 13–30. doi:10.2307/2786866.

Fishbein, M., Hennessy, M., Yzer, M., & Curtis, B. (2004). Romance and risk: romantic attraction and health risks in the process of relationship formation. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 9, 273–285. doi:10.1080/13548500410001721846.

Fuegen, K., & Brehm, J. W. (2004). The intensity of affect and resistance to social influence. In E. S. Knowles & J. A. Linn (Eds.), Resistance and persuasion (pp. 39–63). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gager, C. T., & Sanchez, L. (2003). Two as one? Couples’ perceptions of time spent together, marital quality, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 21–50, doi:10.1177/0192513X02238519.

Gendolla, G. H. E., & Wright, R. A. (2016). Gathering the diaspora: Aims and visions for motivation science. Motivation Science, 2, 135–137. doi:10.1037/mot0000035.

Gonzaga, G. C., Keltner, D., Londahl, E. A., & Smith, M. D. (2001). Love and the commitment problem in romantic relations and friendship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 247–262. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.247.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hillgruber, A. (1912). Fortlaufende Arbeit und Willensbetätigung [Continuos work and will activity]. Leipzig: Quelle und Meyer.

Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2014). Introduction to statistics in psychology (6th ed.). London: Pearson Education Ltd..

Karney, B., & Bradbury, T. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 3–34. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3.

Kline, G. H., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., Olmos-Gallo, P. A., St. Peters, M., Whitton, S. W., & Prado, L. M. (2004). Timing is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 311–318. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.311.

Lehmiller, J. J., & Agnew, C. R. (2006). Marginalized relationships: The impact of social disapproval on romantic relationship commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 40–51. doi:10.1177/014616720527871.

Levinger, G. (1999). Duty toward whom? Reconsidering attractions and barriers as determinants of commitment in a relationship. In W. H. Jones & J. M. Adams (Eds.). Handbook of interpersonal commitment and relationship stability (pp. 37–52). New York: Plenum.

McGue, M., & Lykken, D. T. (1992). Genetic influence on risk of divorce. Psychological Science, 3, 368–373. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00049.x.

Meuwly, N., & Schoebi, D. (2017). Social psychological and related theories on long-term committed romantic relationships. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11, 106–120. doi:10.1037/ebs0000088.

Miron, A. M., Brummett, B., Ruggles, B., & Brehm, J. W. (2008). Deterring anger and anger-motivated behaviors. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30, 326–338. doi:10.1080/0197353080250225.

Miron, A. M., Ferguson, M. A., & Peterson, A. (2011). Difficulty of refusal to assist the outgroup nonmonotonically affects the intensity of prejudiced affect. Motivation and Emotion, 45, 484–498. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9220-2.

Miron, A. M., Knepfel, D., & Parkinson, S. K. (2009). The surprising effect of partner flaws and qualities on romantic affect. Motivation and Emotion, 33, 261–276. doi:10.1007/s11031-009-9138-0.

Miron, A. M., Parkinson, S. K., & Brehm, J. W. (2007). Does happiness function like a motivational state?. Cognition and Emotion, 21, 248–267. doi:10.1080/02699930600551493.

Miron, A. M., Rauscher, F. H., Reyes, A., Gavel, D., & Lechner, K. K. (2012). Full-dimensionality of relating in romantic relationships. Journal of Relationships Research, 3, 67–80. doi:10.1017/jrr.2012.8.

Monroe, S. M., Rohde, P., Seeley, J. R., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (1999). Life events and depression in adolescence: Relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset of major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 606–614. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.108.4.606.

Murray, S. L., Derrick, J. L., Leder, S., & Holmes, J. G. (2008). Balancing connectedness and self-protection goals in close relationships: A levels-of-processing perspective on risk regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 429–459. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.429.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Collins, N. L. (2006). Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 641–666. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641.

Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2004). How does context affect intimate relationships? Linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 134–148. doi:10.1177/0146167203255984.

Pantaleo, G. (2011). Enjoying multiplicity: From familiarity to ‘multiple perspectives’. In M. Cadinu, S. Galdi, & A. Maass (Eds.), Social perception, cognition, and language in honour of Arcuri (pp. 51–65). Padua: Cleup.

Pantaleo, G., Miron, A., Ferguson, M., & Frankowski, S. (2014). Effects of deterrence on intensity of group identification and efforts to protect group identity. Motivation and Emotion, 38, 855–865. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9440-3.

Parks, M. R., Stan, C. M., & Eggert, L. L. (1983). Romantic involvement and social network involvement. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46, 116–131. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3033848.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553.

Reysen, S., & Katzarska-Miller, I. (2013). Playing moderately hard to get. An application of Brehm’s emotion intensity theory. Interpersona, 7, 260–271. doi:10.5964/ijpr.v7i2.128.

Rhoades, G. K., Kamp Dush, C. M., Atkins, D. C., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: The impact of unmarried relationship dissolution on mental health and life satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 366–374. doi:10.1037/a0023627.

Richter, M. (2013). A closer look into the multi-layer structure of motivational intensity theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 1–12. doi:10.1111/spc3.12007.

Richter, M. (2015). Goal pursuit and energy conservation: Energy investment increases with task demand but does not equal it. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 25–33. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9429-y.

Richter, M. (2016). Residual tests in the analysis of planned contrasts: Problems and solutions. Psychological Methods, 21, 112–120. doi:10.1037/met0000044.

Richter, M., Brinkmann, K., & Carbajal, I. ((2016)). Effort and autonomic activity: A meta-analysis of four decades of research on motivational intensity theory. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 108, 34. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.07.113.

Richter, M., Gendolla, G. H. E., & Wright, R. A. (2016). Three decades of research on motivational intensity theory: What we have learned about effort and what we still don’t know. Advances in Motivation Science, 3, 149–186. doi:10.1016/bs.adms.2016.02.001.

Roberson, B. F., & Wright, R. A. (1994). Difficulty as a determinant of interpersonal appeal: A social-motivational application of energization theory. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 15, 373–388. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp1503_10.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R.L. (1985). Contrast analysis: Focused comparisons in the analysis of variance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rusbult, C. E. (1980). Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 172–186. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4.

Rusbult, C. E. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 101–117. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.101.

Rusbult, C. E., Agnew, C. R., & Arriaga, X. B. (2012). The investment model of commitment processes. In A. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 218–231). London: Sage.

Rusbult, C. E., & Buunk, B. P. (1993). Commitment processes in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10, 175–204. doi:10.1177/026540759301000202.

Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The Investment Model Scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5, 357–391. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x.

Schmitt, M. T., Miller, D. A., Branscombe, N. R., & Brehm, J. W. (2008). The difficulty of making reparations affects the intensity of collective guilt. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 11, 267–279. doi:10.1177/1368430208090642.

Silvia, P. J., & Brehm, J. W. (2001). Exploring alternative deterrents to emotional intensity: Anticipated happiness, distraction, and sadness. Cognition and Emotion, 15, 575–592. doi:10.1080/02699930125985.

Sinclair, H. C., & Ellithorpe, C. N. (2014). The new story of Romeo and Juliet. In C. R. Agnew (Ed.). Social influences on romantic relationships: Beyond the dyad (Advances in Personal Relationships) (pp. 148–170). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBo9781139333640.010.

Sinclair, H. C., Hood, K., & Wright, B. (2014). Revisiting the Romeo and Juliet effect (Driscoll, Davis, & Lipetz, 1972): Reexamining the links between social network opinions and romantic relationship outcomes. Social Psychology, 45, 170–178. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000181.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. doi:10.2307/270723.

Sprecher, S. (2011). The influence of social networks on romantic relationships: Through the lens of the social network. Personal Relationships, 18, 630–644. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01330.x.

Stanek, J. C., & Richter, M. (2016). Evidence against the primacy of energy conservation: Exerted force in possible and impossible handgrip tasks. Motivation Science, 2, 49–65.doi:10.1037/mot0000028.

VanderDrift, L. E., Agnew, C., & Wilson, J. E. (2009). Non-marital romantic relationship commitment and leave behavior: The mediating role of dissolution consideration. Department of Psychological Sciences Faculty Publications. Paper 25. doi:10.1177/0146167209337543.

Wilkinson, L., & the Task Force on Statistical Inference—APA Board of Scientific Affairs. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54, 594–604. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.594.

Wright, H. F. (1937). The influence of barriers upon strength of motivation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wright, R. A. (2008). Refining the prediction of effort: Brehm’s distinction between potential motivation and motivation intensity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass: Motivation and Emotion, 2, 682–701. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00093.x.

Wright, R. A. (2011). Motivational when motivational wasn’t cool. Chapter. In R. M. Arkin (Ed.), Most underappreciated: 50 prominent social psychologists describe their most unloved work. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wright, R. A. (2016). Motivation theory essentials: Understanding motives and their conversion into effortful goal pursuit. Motivation and Emotion, 40, 16–21. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9536-4.

Wright, R. A., Toi, M., & Brehm, J. W. (1985). Difficulty and interpersonal attraction. Motivation and Emotion, 8, 327–341. doi:10.1007/BF00991871.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sciara, S., Pantaleo, G. Relationships at risk: How the perceived risk of ending a romantic relationship influences the intensity of romantic affect and relationship commitment. Motiv Emot 42, 137–148 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9650-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9650-6