Abstract

Women leave science fields at greater rates than men, and loss of interest is a key motivator for leaving. Although research widely demonstrates effects of gender bias on other motivational processes, whether gender bias directly affects feelings of interest toward science activities is unknown. We used a false feedback paradigm to manipulate whether women (Study 1) and men (Study 2) participants perceived the reason for feedback as due to pro-male bias. Because activity interest also depends on how students approach and perform the activity, effects of biased feedback on interest appraisals were isolated by introducing gender bias only after the science activity was completed. When the feedback was perceived as due to pro-male bias, women (Study 1) reported lower interest and men (Study 2) reported greater interest in the science activity, and interest, in turn, positively predicted subsequent requests for career information in both studies. Implications for understanding diverging science interests between women and men are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Originally there were two pro-male bias conditions, attempting to disentangle stereotypes based on the individual feedback giver’s experience from general domain-based stereotypes. Participant feedback made clear that these conditions were not distinguishable; both were perceived as reflecting domain bias. Confirming that participants did not distinguish these conditions, we compared these conditions on all dependent variables and manipulation checks, finding no differences. Thus, we collapsed into a single pro-male bias condition.

In both studies, no participant reported suspicion in the no feedback condition where individuals performed the activity separately then completed study measures. Among other conditions, the number of participants reporting suspicion was evenly spread, suggesting that participants were not differentially suspicious as a function of the reason for the feedback. In addition, nearly all cases of high suspicion (in both studies) occurred near the end of the academic semester, when there is greater likelihood that participants would have heard about the study from peers or have participated in previous studies that used deception. Participants who were dropped versus retained did not differ on any demographic or individual difference measures. Analyses were re-run including participants who reported high suspicion and all substantive findings were consistent with the reported results.

In both studies we tested for but found no significant differences for any effects across confederates or experimenters.

Pilot testing indicated that the stories were moderately difficult, with at least two answers as equally likely, and that the task was perceived as relevant for learning scientific content and reasoning, characteristics needed for plausibility of the manipulation.

In this model we did not include tests for potential indirect effects of gender bias feedback on activity interest appraisals via perceived competence and competence value because these variables were not significantly predicted by the feedback manipulation (which establishes a lack of X to M relationship in a mediation model). We did conduct these indirect tests in a separate model, however, and as expected no indirect effects on activity interest were significant.

References

Adams, G., Garcia, D., Purdie-Vaughns, V., & Steele, C. (2006). The detrimental effects of a suggestion of sexism in an instruction situation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 602–615. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.004.

Ainley, M. (2006). Connecting with learning: Motivation, affect, and cognition in interest processes. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 391–405. doi:10.1007/s10648-006-9033-0.

American Association of University Women. (2010). Why so few: Women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, by C. Hill, C. Corbett, & A. St. Rose. Washington, DC: Author.

Bergin, D. A. (1999). Influences on classroom interest. Educational Psychologist, 34, 87–92.

Berlyne, D. E. (1966). Curiosity and exploration. Science, 153, 25–33. doi:10.1126/science.153.3731.25.

Berlyne, D. E. (1978). Curiosity and learning. Motivation and Emotion, 2, 97–175. doi:10.1007/BF00993037.

Branscombe, N. R. (1998). Thinking about one’s gender group’s privileges or disadvantages: Consequences for well-being in women and men. British Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 167–184. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1998.tb01163.x.

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2012). Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 3157–3162. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014871108.

Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M., & Barnett, S. M. (2009). Women’s underrepresentation in science: Sociocultural and biological considerations. Psychological Review, 135, 218–261. doi:10.1037/a0014412.

Chaiken, S., & Baldwin, M. W. (1981). Affective–cognitive consistency and the effect of salient behavioral information on the self-perception of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 1–12. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.41.1.1.

Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: How stereotypical environments impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 1045–1060. doi:10.1037/a0016239.

Connelly, D. A. (2011). Appying Silvia’s model of interest to academic text: Is there a third appraisal? Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 624–628. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.007.

Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.608.

Fazio, R. H., Zanna, M. P., & Cooper, J. (1977). Dissonance and self-perception: An integrative view of each theory’s proper domain of application. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(5), 464–479.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 56(2), 276–278.

Heatherton, T. F., & Polivy, J. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 895–910. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.895.

Inzlicht, M., & Schmader, T. (2011). Stereotype threat: Theory, process, and application. New York: Oxford University Press.

Izard, C. E. (1977). Human emotions. New York: Plenum Press.

Izard, C. E., & Ackerman, B. P. (2000). Motivational, organizational, and regulatory functions of discrete emotions. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 253–264). New York: Guilford Press.

Katz, I., Assor, A., Kanat-Maymon, Y., & Bereby-Meyer, Y. (2006). Interest as a motivational resource: Feedback and gender matter, but interest makes the difference. Social Psychology of Education, 9, 27–42. doi:10.1007/s11218-005-2863-7.

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973). Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic rewards: A test of the “overjustification” hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28, 129–137.

Major, B., & O’Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137.

Major, B., Quinton, W. J., & Schmader, T. (2003). Attributions to discrimination and self-esteem: Impact of group identification and situational ambiguity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 220–231. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00547-4.

Major, B., Spencer, S. J., Schmader, T., Wolfe, C. T., & Crocker, J. (1998). Coping with negative stereotypes about intellectual performance: The role of psychological disengagement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 34–50.

Mallett, R. K., & Swim, J. K. (2007). The influence of inequality, responsibility and justifiability on reports of group-based guilt for ingroup privilege. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10, 57–69. doi:10.1177/1368430207071341.

Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. (2004). Children’s search for gender cues: Cognitive perspectives on gender development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(2), 67–70. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00276.x.

Martiny, S. E., Roth, J., Jelenec, P., Steffens, M. C., & Croizet, J. C. (2012). When a new group identity does harm on the spot: Stereotype threat in newly created groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 65–71. doi:10.1002/ejsp.840.

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences, 109, 16474–16479. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109.

Murphy, M. C., Steele, C. M., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Signaling threat: How situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings. Psychological Science, 18, 879–885. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01995.x.

Pasupathi, M., & Rich, B. (2005). Inattentive listening undermines self-verification in personal storytelling. Journal of Personality, 73, 1051–1086. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00338.x.

Patterson, M. M., & Bigler, R. S. (2007). Relations among social identities, intergroup attitudes, and schooling: Perspectives from intergroup theory and research. In A. Fuligni (Ed.), Contesting stereotypes and creating identities (pp. 15–41). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44, 1–14. doi:10.1080/00461520902832392.

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2011). Revisiting the conceptualization, measurement, and generation of interest. Educational Psychologist, 46, 168–184. doi:10.1080/00461520.2011.587723.

Renninger, K. A. & Schofield, L. S. (2012). Measuring interest: The open-ended response in a large scale survey. In M. D. Ainley (Chair), Assessment of interest: New approaches, new insights. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Rosenthal, H. E. S., Crisp, R. J., & Suen, M.-W. (2007). Improving performance expectancies in stereotypic domains: Task relevance and the reduction of stereotype threat. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 586–597.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (2008). Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rudman, L. A., Dohn, M. C., & Fairchild, K. (2007). Implicit self-esteem compensation: Automatic threat defense. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 798–813. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.798.

Sansone, C. (1986). A question of competence: The effects of competence and task feedback on intrinsic interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 918–931. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.918.

Sansone, C., & Berg, C. A. (1993). Adapting to the environment across the life span: Different process or different inputs? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 16, 379–390. doi:10.1177/016502549301600207.

Sansone, C., & Thoman, D. B. (2005). Interest as the missing motivator in self-regulation. European Psychologist, 10(3), 175–186. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.10.3.175.

Sansone, C., Thoman, D. B., & Fraughton, T. (2015). The relation between interest and self-regulation in mathematics and science. In K. A. Renninger, M. Neiswandt, & S. Hidi (Eds.), Interest in mathematics and science learning. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Schiefele, U., Krapp, A., & Winteler, A. (1992). Interest as a predictor of academic achievement: A meta-analysis of research. In K. A. Renninger, S. Hidi, & A. Krapp (Eds.), The role of interest in learning and development (pp. 183–212). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schmader, T., Major, B., Eccleston, C. P., & McCoy, S. K. (2001). Devaluing domains in response to threatening intergroup comparisons: Perceived legitimacy and the status value asymmetry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 782–796. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.782.

Schmitt, M., Behner, R., Montada, L., Muller, L., & Muller-Fohrbrodt, G. (2000). Gender, ethnicity, and education as privileges: Exploring the generalizability of the existential guilt reaction. Social Justice Research, 13, 313–337. doi:10.1023/A:1007640925819.

Schmitt, M., & Branscombe, N. (2002). The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. European Review of Social Psychology, 12, 167–199.

Sechrist, G. B., & Stangor, C. (2001). Perceived consensus influences intergroup behavior and stereotyped accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 645–654. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.4.645.

Seymour, E., & Hewitt, N. M. (1997). Talking about leaving: Why undergraduates leave the sciences. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Sherman, J. (1981). Girls’ and boys’ enrollments in theoretical math courses: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5(5), 681–689. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1981.tb01092.x.

Silvia, P. J. (2006). Exploring the psychology of interest. New York: Oxford University Press.

Silvia, P. J. (2008). Interest—The curious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 57–60. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00548.x.

Smith, J. L., Lewis, K. L., Hawthorne, L., & Hodges, S. D. (2013). When trying hard isn’t natural: Women’s belonging with and motivation for male-dominated fields as a function of effort expenditure concerns. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 131–143. doi:10.1177/0146167212468332.

Smith, J. L., Sansone, C., & White, P. H. (2007). The stereotyped task engagement process: The role of interest and achievement motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 99–114. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.99.

Stangor, C., Swim, J. K., Van Allen, K. L., & Sechrist, G. B. (2002). Reporting discrimination in public and private contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 69–74. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.69.

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 261–302.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52, 613–629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613.

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). New York: Academic Press.

Stone, J., & Cooper, J. (2001). A self-standards model of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 228–243.

Su, R., Rounds, J., & Armstrong, P. I. (2009). Men and things, women and people: A meta-analysis of sex differences in interests. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 859–884. doi:10.1037/a0017364.

Tesser, A., Martin, L. L., & Cornell, D. P. (1996). On the substitutability of self-protective mechanisms. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action. New York: The Guilford Press.

Thoman, D. B., Sansone, C., Fraughton, T., & Pasupathi, M. (2012). How students socially evaluate interest: Peer responsiveness influences evaluation and maintenance of interest. Contemporary Educational Psychology,. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.04.001.

Thoman, D. B., Sansone, C., & Pasupathi, M. (2007). Talking about interest: Exploring the role of social interaction for regulating motivation and the interest experience. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(3), 335–370.

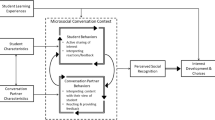

Thoman, D. B., Smith, J. L., Brown, E. R., Chase, J. P., & Lee, J. K. (2013). Beyond performance: The motivational experience model of stereotype threat. Educational Psychology Review, 25, 211–243. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9219-1.

Thoman, D. B., Smith, J. L., & Silvia, P. J. (2011). The resource replenishment function of interest. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 592–599. doi:10.1177/1948550611402521.

Tomkins, S. S. (1962). Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol 1. The positive affects. New York: Springer.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2003). Stereotype lift. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 456–467. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82.

Woodzicka, J. A., & LaFrance, M. (2001). Real versus imagined gender harassment. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 15–30. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00199.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thoman, D.B., Sansone, C. Gender bias triggers diverging science interests between women and men: The role of activity interest appraisals. Motiv Emot 40, 464–477 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9550-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9550-1