Abstract

Urothelial carcinoma of bladder (UBC), a highly prevalent urological malignancy associated with high mortality and recurrence rate. Standard diagnostic method currently being used is cystoscopy but its invasive nature and low sensitivity stresses for identifying predictive diagnostic marker. Autophagy, a cellular homeostasis maintaining process, is usually dysregulated in cancer and its role is still enigmatic in UBC. In this study, 30 UBC patients and healthy controls were enrolled. Histopathologically confirmed tumor and adjacent normal tissue were acquired from patients. Molecular expression and tissue localization of autophagy-associated molecules (HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, LC-3, and p62) were investigated. Serum HMGB-1 concentration was measured in UBC patients and healthy controls. ROC curves were plotted to evaluate diagnostic potential. Transcript, protein, and IHC expression of HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, and LC-3 displayed upregulated expression, while p62 was downregulated in bladder tumor tissue. Serum HMGB-1 levels were elevated in UBC patients. Transcript and circulatory levels of HMGB-1 showed positive correlation and displayed a positive trend with disease severity. Upon comparison with clinicopathological parameters, HMGB-1 emerged as molecule of statistical significance to exhibit association. HMGB-1 exhibited optimum sensitivity and specificity in serum. The positive correlation between tissue and serum levels of HMGB-1 showcases serum as a representation of in situ scenario, suggesting its clinical applicability for non-invasive testing. Moreover, optimum sensitivity and specificity displayed by HMGB-1 along with significant association with clinicopathological parameters makes it a potential candidate to be used as diagnostic marker for early detection of UBC but requires further validation in larger cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary Bladder Cancer is the second most common malignant neoplasm of the urinary tract which originates from the urothelium. Primary histological subtype of bladder cancer is urothelial carcinoma of bladder (UBC) which occurs at a high rate of > 90% [1]. It is the 10th most common cause of cancer-related death and is associated with high recurrence rate [2]. Early detection of UBC is important for proper diagnosis and better patient outcomes to achieve curability for disease. Numerous clinical procedures are available for diagnosis of UBC, but lack of efficacy necessitates the need for identification of a novel molecular marker that can be detected non-invasively with optimum sensitivity and specificity [3]. Our lab has been working in the area of UBC for past two decades [4,5,6]. The diagnostic potential of certain molecules has also been assessed in UBC [7,8,9].

Cancer cell is composed of a heterogeneous cell population wherein the extracellular matrix (ECM) forms a major structural component of the tumor microenvironment. ECM is known to influence the various cancer hallmarks and therefore studies are now focusing on specialized ECM-based cultures to explore these interactions [10]. One such hallmarks of cancer is its ability to circumvent cell death and autophagy is known to modulate this feature of cancer. Autophagy is a lysosomal degradation pathway that plays a role in maintaining cellular homeostasis which operates at basal level in normal condition but is dysregulated in various pathological conditions, including cancer [11]. Conceptual advancements made in cancer biology have shown autophagy to act as double-edged sword to either promote or suppress tumor growth [12, 13].

In UBC, few studies have reported the involvement of autophagy in tumor progression; however, only limited studies have highlighted the role of autophagy in UBC patients, while no such study has been reported in Indian patients [14, 15]. Thus, due to lack of general consensus regarding the role of autophagy in UBC patients, a better understanding of interaction between autophagy and tumorigenesis in UBC patients is required.

Autophagy functions through coordinated action of Atg (Autophagy-associated gene) products but there are a plethora of molecules acting as regulators and effectors of autophagy. High-mobility group box-1 (HMGB-1) is one such key regulator for autophagy in response to cellular stress, including tumorigenesis [16].

HMGB-1 is a multifunctional protein that has location-dependent role in regulation of autophagy. It is located in nucleus but under stressful conditions, it can translocate to cytoplasm [17]. It regulates autophagy by interacting with beclin also known as beclin-1, to release it free to help in autophagosome formation leading to autophagy [17]. It can also release into the extracellular milieu by cancer cells and act as ligand for various receptors. One such receptor is receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) which interacts with HMGB-1 to induce beclin-dependent autophagy [18].

Autophagy is an intricate mechanism in which various molecules, including Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC-3), are involved in autophagosome completion [19]. It exists as LC-3B(I) which gets lipidated with phosphatidylethanolamine to form LC-3B(II) and gets incorporated into autophagosome. Also, autophagy is a highly selective process and this selectivity is achieved with help of adaptor molecules like p62, which eliminates ubiquitinated proteins destined for autophagic degradation via LC-3II leading to autophagosome completion [19].

There are limited reports available for the molecules associated with autophagy (HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, LC-3, and p62) in UBC patients. Moreover, the diagnostic significance of these molecules has not been taken into consideration to date in UBC. Given this knowledge gap in dissecting the role of autophagy in UBC, in this maiden attempt, we aim to study the diagnostic potential of HMGB-1 and its associated molecules in bladder cancer. To achieve this hypothesis, circulatory levels of HMGB-1 were determined and the molecular expression and immunohistochemistry of HMGB-1 and its associated molecules were studied in study subjects. Their association with clinical parameters was evaluated and lastly, their diagnostic potential was assessed by determining the sensitivity and specificity in UBC patients.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

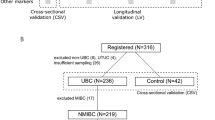

This study has been approved by Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IECPG-692/31.01.2018) prior to its commencement. 30 UBC patients undergoing radical cystectomy were recruited from the Department of Urology, AIIMS, New Delhi. Histopathologically proven tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue were obtained from patients during surgery after obtaining prior written consent. After excision, tissues were collected in RNA later (Invitrogen) for RNA isolation and stored at − 80 °C. Tissues were stored for western blotting and were also immersed in 10% formalin for immunohistochemistry. 5 ml blood sample was also collected from patients and thirty age and sex-matched healthy volunteers in plain vial free of endotoxins for isolation of serum which was stored at −80 °C till further use.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

To determine the circulatory levels of HMGB-1 in UBC patients, ELISA was performed in serum samples. HMGB-1 levels were also assessed in tissue lysate of study subjects for which tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer and then quantified by Bradford assay. Concentration of HMGB-1 was quantified with a commercial ELISA kit supplied by USCN Cloud Clone Corporation (Houston, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions, while in tissue lysate, HMGB-1 levels were normalized by total protein concentration.

Gene expression analysis by real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted by chloroform–ethanol precipitation method from snapped frozen tissue using Trizol (Sigma-Aldrich). Further, RNA was transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher). The cDNA synthesized was used as template to analyze gene amplification using Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System, USA. The relative mRNA expression was calculated using 2−δCt method where Ct values of the molecules were normalized to that of 18S rRNA and compared with their respective controls. Primer sequences used are mentioned in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blotting

Tissue samples were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail for whole-cell lysate. For nuclear and cytoplasmic lysate, tissues were lysed in buffer (10 mM HEPES,1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.05% NP40) along with protease inhibitor cocktail and incubated on ice for 10 min. Then they were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min and supernatant was kept as cytoplasmic lysate. Remaining pellet was washed with 1X PBS and resuspended in buffer (5 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 26% glycerol (v/v), and NaCl). Lysate was sonicated followed by 45-min incubation and centrifuged at 20,000×g for 20 min to collect supernatant as nuclear lysate. Protein quantification was done by Bradford assay. 20–30 µg of total protein for whole-cell lysate and 10–20 µg for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were resolved in SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane was blocked with 5% BSA for 45 min followed by primary antibody incubation overnight at 4 °C. HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was added. Blot was developed with chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific). Band images were acquired with Azure c600 gel doc system followed by quantification using ImageJ analyzer software. Details of antibodies used are mentioned in Supplementary Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue specimens were fixed using 10% formalin following which they were paraffin embedded and blocks were prepared and tissues were mounted onto Poly-l-lysine-coated slides. Antigen retrieval was done using citrate buffer (pH = 6) for 20 min. Primary antibody was standardized on appropriate positive controls using different dilution ranges. Final dilution of these antibodies (Supplementary Table 3) was used for staining slides overnight. After washing, biotinylated secondary antibody was added and incubated for 30 min, then HRP-tagged antibody was added, and lastly diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used as chromogen. Tissue expression was quantified using immunoreactive score as described previously [20]. The score criterion according to staining intensity was defined for protein expression as: 0-low and 1-high.

Correlation analysis

Spearman correlation analysis was performed to correlate the gene expression of all the molecules with each other in tumor specimen of patients. Further, the correlation between circulatory and intracellular levels of HMGB-1 was done. Transcript and circulatory levels of HMGB-1 were also correlated. Spearman correlation test was performed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient with a confidence interval of 95% and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

All the data analyses and representations were performed either using GraphPad Prism 5.0 or Stata 12.0. Data were represented as median (range) or mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis statistical test was adopted for comparing more than two groups for stage-wise analysis otherwise for two groups, Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test was used. To determine the association of the given molecules with various clinicopathological parameters, Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for analysis having two groups. Statistical analysis of more than two groups was performed using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test for pairwise comparisons, if required with Bonferroni adjustments in p value for multiple comparisons. To determine the diagnostic potential of autophagy-associated molecules, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted for serum, tissue lysate, and transcript levels of UBC patients. Cut-off values along with sensitivity and specificity and area under the curve were determined. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05 with confidence interval of 95%.

Results

Study subjects

Patient demographic data are depicted in Table 1. According to histological grading, majority of patients were high grade (18) and rest low grade (12). On pathological tumor staging (pT) according to WHO staging (2016), UBC patients were categorized as pT0, pT1, pT2, and pT3 stages.

Circulatory and intracellular levels of HMGB-1

The circulatory levels of HMGB-1 were found to be significantly elevated (p < 0.001) in UBC patients as compared to healthy controls and displayed an increasing trend with disease severity (p < 0.01) [Fig. 1A]. Also, the intracellular levels of HMGB-1 in tissue lysates were determined [Fig. 1B] wherein a considerable upregulation (p < 0.05) was detected in tumor tissue in comparison to adjacent normal tissue. A significant elevation (p < 0.01) was observed in high-grade lysate as compared to its normal counterpart.

Relative expression of autophagy-associated molecules in circulation and tissue of UBC patients. A Circulatory levels of HMGB-1 in serum of UBC patients (n = 30; n = 12 low grade; n = 18 high grade) and healthy controls (n = 30). Concentration is denoted as pg/ml. B Levels of HMGB-1 in tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue lysates of bladder cancer patients (n = 10 tumor tissue; n = 5 low-grade tumor; n = 5 high-grade tumor) and adjacent normal tissue (n = 10). Levels of HMGB-1 determined in tissue were normalized by total protein concentration. Concentration is denoted as pg/μg of total protein. C–G Box whisker plot depicting the relative mRNA expression of HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, LC-3, and p62 in UBC patients (n = 30 tumor tissue; n = 12 low grade; n = 18 high grade) and (n = 30 adjacent normal tissue). 18S was used as an endogenous control for normalization. The data were represented as median (range). Kruskal–Wallis statistical test was adopted for analysis. [HMGB-1: high-mobility group box-1, RAGE: receptor for advanced glycation end products, LC-3: microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001]

Relative mRNA expression of autophagy-associated HMGB-1 and its related molecules

The relative mRNA expression of HMGB-1 was significantly enhanced (p < 0.001) in tumor tissue in comparison to adjacent normal tissue and showed positive trend with increase in disease severity (p < 0.01). High-grade tumors depicted more significant upregulation (p < 0.001) of HMGB-1 than normal tissue, while for low-grade tumors the increase was insignificant.

RAGE has shown significantly heightened mRNA expression (p < 0.001) in tumor tissue in comparison to non-tumor tissue but showed no correlation with disease severity. Its expression was significantly increased in high grade (p < 0.01) and low-grade (p < 0.05) tissue than in adjacent normal tissue.

Highbeclin mRNA expression (p < 0.001) was observed in cancer tissue as compared to normal counterparts and displayed a gradual increase with disease progression (p < 0.01). A significantly upregulated expression of beclin was found in high-grade tissue (p < 0.001) than normal tissue.

LC-3 was significantly upregulated (p < 0.001) in tumor tissue in comparison to adjacent normal tissue. LC-3 levels were elevated in high grade (p < 0.01) and low-grade tumor (p < 0.001) as compared to non-tumor tissue, while no correlation with disease severity was seen.

p62 gene transcription exhibited significantly reduced expression (p < 0.001) in UBC tissue than in non-tumor tissue. Decrease in the expression of p62 was more pronounced in high grade (p < 0.001) and low-grade tumors (p < 0.01) than in normal tissue [Fig. 1C–G].

Western blotting analysis of autophagy-associated HMGB-1 and its related molecules

After validating gene expression of given molecules, their protein expression was studied in UBC patients by western blotting [Fig. 2A]. Expression of RAGE (p < 0.001) and LC-3 (p < 0.05) was significantly elevated in tumor tissue in comparison to adjacent normal tissue, while for beclin upregulation observed was insignificant. In contrast, p62 expression was detected to be significantly downregulated (p < 0.05) in tumor tissue. Moreover, HMGB-1 expression was assessed in nuclear and cytoplasmic lysate [Fig. 2B, C]. Increased cytoplasmic (p < 0.01) and decreased nuclear expression of HMGB-1 was observed in tumor tissue compared with non-tumor tissue.

Determination of protein levels of HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, LC-3, and p62 in UBC patients. A Immunoblot image showing the protein expression of RAGE, beclin, LC-3, and p62 in whole-cell lysate of tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue (n = 10 each) by western blotting (left panel). Expression of β-actin was monitored to ensure uniform protein loading in all lanes. ImageJ densitometry analysis (right panel) depicting the fold change of protein expression. B, C Protein expression of HMGB-1 in nuclear and cytoplasmic lysate of tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue (n = 10 each) by western blotting (left panel). Histone-H3 and β-actin were used as endogenous controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic lysate, respectively. ImageJ densitometry analysis (right panel) was shown. Represented as Intensity ± SD. Student’s t test was used to compare two groups. [HMGB-1: high-mobility group box-1, RAGE: receptor for advanced glycation end products, LC-3: microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001]

Tissue localization by immunohistochemistry

To investigate localization of proteins studied, IHC was performed in confirmed bladder tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue (Fig. 3).

Immunohistochemical expression patterns in tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue of UBC patients. A Representative cases of UBC patients showing staining for HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, LC-3, and p62 in tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue of UBC patients. Scale bar, (100 µm). B Graph showing Immunoreactive Score (IRS) for the molecules in paired tumor (n = 10 tumor tissue; n = 4 low grade; n = 6 high grade) and adjacent normal tissue (n = 10). Immunoreactivity was calculated by multiplying individual score (i.e., intensity score × percentage score) for analysis of protein expression. Kruskal–Wallis test was adopted for statistical analysis. [HMGB-1: high-mobility group box-1, RAGE: receptor for advanced glycation end products, LC-3: microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001]

High HMGB-1 protein levels were detected in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments in tumor tissue (p < 0.05). Normal urothelium had lower levels of HMGB-1 protein with similar distribution. HMGB-1 expression was maximal in high-grade tumors (p < 0.05) compared to low-grade tumors whose expression was comparable to adjacent normal tissue. Accordingly, HMGB-1 receptor RAGE expression was also considerably elevated in tumor tissue than neighboring non-tumor tissue (p < 0.05).

Beclin displayed variable levels of cytoplasmic staining ranging from weak to moderate expression in the tumor tissue, while weak cytoplasmic expression was seen in normal urothelium. LC-3 showed strong cytoplasmic and moderate nuclear staining in tumor tissues. In normal urothelium, its expression was relatively weak. Meanwhile, p62 levels were reduced in urothelial carcinoma tissue, whereas normal urothelium showed strong cytoplasmic expression but was statistically insignificant.

Correlation analysis

HMGB-1 transcripts levels exhibited a positive correlation with RAGE and beclin in UBC tissues (Supplementary Table 4). Next, the circulatory and tissue levels of HMGB-1 were correlated but were statistically insignificant which might be due to small sample size [Fig. 4A]. However, a significant positive correlation of HMGB-1 between transcript and circulatory levels was observed (p < 0.001) [Fig. 4B] which could depict serum as a true representation of in situ scenario in UBC.

Association of HMGB-1 with various parameters in serum and tissue correlation analysis of HMGB-1 in UBC patients with following parameters. A Graph showing the correlation analysis of HMGB-1 levels comparing the circulatory levels in serum and tissue levels in tissue lysate of the UBC patients. B Graph showing the correlation analysis of HMGB-1 levels between transcript and circulatory levels in UBC patients. C, D Box whisker plot showing the association of HMGB-1 C relative mRNA expression in the tumor tissue and D serum of UBC patients with histological grade, muscle invasion, and pT Stage. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing the levels of HMGB-1in E serum and F tissue lysate, respectively, to determine the diagnostic potential. The graphs showcase the optimum sensitivity and specificity and area under curve along with cut-off values for serum levels and intercellular levels, respectively. For A and B Spearman correlation analysis was used to determine correlation. For C and D median (range) is represented. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used between two groups. Statistical analysis of more than two groups were performed using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test for pairwise comparisons, if required with Bonferroni corrections in p value was used for multiple comparisons. [HMGB-1: high-mobility group box-1, r = Spearman correlation coefficient, pT stage: pathological tumor stage, NMI: non-muscle invasive, MI: muscle invasive, AUC: area under curve. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001]

Association of autophagy-associated molecules with clinicopathological features in urothelial carcinoma of bladder

The transcript levels of autophagy-associated molecules were tested for their association with clinicopathological parameters of UBC patients as shown in Table 2 among which only HMGB-1 presented a significant association with histological grade and pT stage wherein pT0 + pT1 and pT3 stage patients exhibited significant association (p < 0.001) [Fig. 4C]. Circulatory levels of HMGB-1 showed significantly strong association with histological grade, muscle invasion, and pT stage [Table 3]. A significant association was observed for pT0 + pT1 with pT2 (p < 0.01) and pT3 stages (p < 0.001) [Fig. 4D].

Assessment of diagnostic potential

To assess the diagnostic potential of given molecules in UBC patients, ROC curves were plotted. HMGB-1 exhibited optimum sensitivity and specificity for both serum and tissue lysates [Fig. 4E, F] with AUC being 0.86 and 0.85, respectively. Further, the mRNA expression of given molecules was assessed (Supplementary Fig. 1), out of which HMGB-1 emerged to have an optimum sensitivity and specificity with AUC (0.86), showcasing the diagnostic potential of HMGB1 in UBC.

Discussion

UBC is associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity worldwide, causing an estimated 150,000 deaths annually [2, 21]. Approximately 75% of newly diagnosed cases represent non-muscle invasive bladder cancer which are associated with high rates of recurrence. While rest are muscle invasive bladder cancer leading to maximum UBC-associated fatalities [1]. With the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic there has been a surge in the fatality of the patients already suffering from UBC and infected with SARS-CoV-2. A recent study by Akan et al. have reported that patients with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer receiving intravesical BCG therapy are at greater risk to be infected with Covid-19 infection [22]. Immunological impairment is one of the major reasons for this infection. Studies have shown different aspects targeting the immunological impairment and one of the pathway is complement system to curb the disease [23,24,25]. The increased fatality in UBC is due to delayed diagnosis of the disease. Cystoscopy has been the mainstay for detection and surveillance of UBC but still associated with false-negative rate and its invasive nature causes patient discomfort and stress. Non-invasive tests like urine cytology are associated with low sensitivity, while FDA-approved tumor markers have been limited by low clinical specificity and high false-positive rate [3]. Therefore, an ideal marker is essential that can diagnose UBC at an early stage without requisite of invasive testing and easily distinguish healthy individuals from UBC patients with optimum sensitivity and specificity.

To circumvent cell death, tumors have established various strategies among which involve their ability to modulate the cell machinery via autophagy. HMGB-1 plays a pivotal role in autophagy induction in cytoplasm by interacting with beclin. It mediates concomitant downstream signaling to initiate autophagy by interacting with RAGE. LC-3 is involved in the intricate core machinery of autophagy which helps in autophagosome completion and interacts with p62 for selective degradation of ubiquitinated proteins.

Autophagy has been studied in carcinomas of other anatomical sites but in UBC, its role is still enigmatic. Limited reports are available exploring the role of autophagy-associated molecules in UBC. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the role of all these molecules collectively and diagnostic potential of HMGB-1 in a single study in UBC.

HMGB-1 is selectively released from cancer cells into circulation; therefore, its circulatory levels were investigated which were observed to be significantly upregulated in UBC patients in comparison to healthy volunteers and exhibited a positive trend with disease severity. These results are in concordance with earlier reports in various tumors [26, 27]. Intracellular levels of HMGB-1 were also elevated in tumor tissue. This is the maiden study showcasing the serum and intracellular levels of HMGB-1 in UBC patients. Transcript levels of HMGB-1 were significantly higher in tumor tissue as compared to adjacent normal tissue and correlated with disease severity which has been previously exemplified in UBC [20, 28].

Next to study the autophagy-induced translocation of HMGB-1 in tumor tissue, protein levels of HMGB-1 were assessed in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction wherein predominant increase of cytoplasmic HMGB-1 was observed in tumor tissue compared to adjacent normal tissue. Our findings are in concordance with an earlier report in colon cancer wherein high cytoplasmic HMGB-1 was detected in tumor tissue [29], while no such report is available in UBC. Immunohistochemical analysis also showed significant HMGB-1 localization in tumor tissue which supports the previous findings in UBC [20, 28].

RAGE is one of the binding receptors for HMGB-1 and accumulating data has shown its role in tumorigenesis [27, 30]. The transcript levels of RAGE exhibited significant elevation in tumor tissue and agrees with a previous report in UBC [31]. Protein levels and immunohistochemistry of RAGE in UBC were significantly increased in tumor tissue and are in concordance with a report by Qian et al. [30].

HMGB-1 helps to regulate autophagy by interacting with beclin, an important initiator protein for autophagy. The relative gene expression of beclin was significantly enhanced in bladder cancer tissue than in adjacent normal tissue and displayed a trend with disease progression. Moreover, the protein expression and tissue localization of beclin was upregulated in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue but was statistically insignificant. Admittedly, these findings are in disconcordance with previous studies in UBC showing decreased beclin expression in tumor tissue [32, 33]. But in parallel, reports in other solid tumors have shown elevated expression of beclin to be associated with tumor progression [34,35,36].

LC-3 is crucial for autophagy, and molecular expression of LC-3 was significantly increased while immunopositivity was high in UBC tissue than in normal urothelium. Upregulation of LC-3 has been documented before in various solid tumors [35, 37, 38] and a single study in UBC [39].

Besides, the molecular expression of p62 were significantly downregulated in tumor tissue and its tissue localization also showed decreased expression but was statistically non-significant. These results are in agreement with reports in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma showing a decrease in p62 levels [37]. Alternately, a recent study in UBC has reported an upregulation of p62 in bladder tumor tissue [40].

A positive correlation was observed between HMGB-1 with RAGE and beclin at mRNA levels in tumor tissue of UBC patients. This suggests the plausible involvement of HMGB-1–RAGE signaling in tumorigenesis and autophagy upregulation via beclin but requires further validation of downstream signaling in UBC. In accordance with these results in UBC, a related study showed autophagy-mediated HMGB-1 to be involved in gastric cancer progression by binding to RAGE receptor and activating downstream ERK1/2 signaling [27]. Similarly, a recent study by Lai et al. in acute leukemia has shown extracellular HMGB-1 interaction with RAGE in cancer cells and have a role in drug resistance after chemotherapy mainly by activating autophagy [41]. Also, HMGB-1 displayed a significant positive correlation between serum and transcript levels. Upon clinicopathological association the transcript and circulatory levels of HMGB-1 exhibited a significant positive association with tumor stage, grade, and muscle invasiveness. These findings suggest the clinical utility of serum as a true representation of UBC tissue. To assess the diagnostic performance of HMGB-1, ROC curves were plotted and exhibited optimum sensitivity and specificity at serum, intracellular, and transcript level and are in concordance with previous report in serum of colorectal cancer patients [26], while no such study is available in UBC. Moreover, the diagnostic accuracy displayed by HMGB-1 highlights its diagnostic efficacy and clinical applicability.

Overall, this study tried to unravel the status of autophagy in UBC wherein an upregulation of HMGB-1, RAGE, beclin, and LC-3, while downregulation of p62 was observed in UBC patients. Although controversial results were also available for beclin and p62, wherein these differences might be due to ethnic diversity as the current study was performed in Indian population and therefore requires further investigation. Correlation between the transcript and the circulatory levels of HMGB-1 in UBC patients highlights serum as a true representation of in situ scenario making it a suitable candidate for non-invasive marker for UBC detection. Besides, HMGB-1 emerged as a molecule of statistical significance to be positively associated with clinicopathological parameters. High sensitivity and specificity demonstrated by HMGB-1 showcase its diagnostic accuracy in serum. These results suggest that HMGB-1 might be a useful diagnostic marker for pre-operative assessment of UBC patients but warrants further validation in a larger cohort for it to be used in clinical settings in future.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Kamat AM et al (2016) Bladder cancer. Lancet 388(10061):2796–2810. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30512-8

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492

Smith ZL, Guzzo TJ (2013) Urinary markers for bladder cancer. F1000Prime Rep. https://doi.org/10.12703/P5-21

Anand V et al (2019) CD44 splice variant (CD44v3) promotes progression of urothelial carcinoma of bladder through Akt/ERK/STAT3 pathways: novel therapeutic approach. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145(11):2649–2661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-019-03024-9

Khandelwal M et al (2020) RASSF1A–hippo pathway link in patients with urothelial carcinoma of bladder: plausible therapeutic target. Mol Cell Biochem 464(1–2):51–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-019-03648-y

Khandelwal M et al (2018) Decitabine augments cytotoxicity of cisplatin and doxorubicin to bladder cancer cells by activating hippo pathway through RASSF1A. Mol Cell Biochem 446(1–2):105–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-018-3278-z

Appunni S, Anand V, Khandelwal M, Seth A, Mathur S, Sharma A (2017) Altered expression of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (decorin, biglycan and lumican): plausible diagnostic marker in urothelial carcinoma of bladder. Tumour Biol 39(5):101042831769911. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010428317699112

Bhagirath D, Abrol N, Khan R, Sharma M, Seth A, Sharma A (2012) Expression of CD147, BIGH3 and Stathmin and their potential role as diagnostic marker in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Chim Acta 413(19–20):1641–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2012.05.005

Satyam A, Singh P, Sharma M, Seth A, Sharma A (2011) CYFRA 21–1: a potential molecular marker for noninvasive differential diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of bladder. Biomarkers 16(5):413–421. https://doi.org/10.3109/1354750X.2011.582152

Satyam A, Tsokos MG, Tresback JS, Zeugolis DI, Tsokos GC (2020) Cell-derived extracellular matrix-rich biomimetic substrate supports podocyte proliferation, differentiation, and maintenance of native phenotype. Adv Funct Mater 30(44):1908752. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201908752

Mizushima N (2007) Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev 21(22):2861–2873. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1599207

White E (2012) Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 12(6):401–410. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3262

Zhang B, Liu L (2021) Autophagy is a double-edged sword in the therapy of colorectal cancer (review). Oncol Lett 21(5):1–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2021.12639

Chandrasekar T, Evans CP (2016) Autophagy and urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a review. Investig Clin Urol 57(Suppl 1):S89. https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2016.57.S1.S89

Konac E, Kurman Y, Baltaci S (2021) Contrast effects of autophagy in the treatment of bladder cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 246(3):354–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370220959336

Tang D, Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT (2010) High-mobility group box 1 [HMGB1] and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1799(1–2):131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.014

Tang D et al (2010) Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J Cell Biol 190(5):881–892. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200911078

Tang D et al (2010) HMGB1 release and redox regulates autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells. Oncogene 29(38):5299–5310. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2010.261

Bento CF et al (2016) Mammalian autophagy: how does it work? Annu Rev Biochem 85(1):685–713. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014556

Huang Z et al (2015) Down-regulation of HMGB1 expression by shRNA constructs inhibits the bioactivity of urothelial carcinoma cell lines via the NF-κB pathway. Sci Rep 5(1):12807. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12807

Sanli O et al (2017) Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3(1):17022. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.22

Akan S, Ediz C, Kızılkan YE, Alcin A, Tavukcu HH, Yilmaz O (2021) COVID-19 infection threat in patients with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer receiving intravesical BCG therapy. Int J Clin Pract 75(3):e13752. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13752

Jamaly S et al (2021) Complement activation and increased expression of Syk, mucin-1 and CaMK4 in kidneys of patients with COVID-19. Clin Immunol 229:108795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2021.108795

Satyam A, Tsokos GC (2020) Curb complement to cure COVID-19. Clin Immunol 221:108603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108603

Satyam A, Tsokos MG, Brook OR, Hecht JL, Moulton VR, Tsokos GC (2021) Activation of classical and alternative complement pathways in the pathogenesis of lung injury in COVID-19. Clin Immunol 226:108716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2021.108716

Lee H et al (2012) Diagnostic significance of serum HMGB1 in colorectal carcinomas. PLoS ONE 7(4):e34318. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034318

Zhang Q-Y, Wu L-Q, Zhang T, Han Y-F, Lin X (2015) Autophagy-mediated HMGB1 release promotes gastric cancer cell survival via RAGE activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2. Oncol Rep 33(4):1630–1638. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2015.3782

Wang W et al (2013) Overexpression of high mobility group box 1 and 2 is associated with the progression and angiogenesis of human bladder carcinoma. Oncol Lett 5(3):884–888. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2012.1091

Kang HJ et al (2009) Non-histone nuclear factor HMGB1 is phosphorylated and secreted in colon cancers. Lab Investig 89(8):948–959. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2009.47

Qian F, Xiao J, Gai L, Zhu J (2019) HMGB1-RAGE signaling facilitates Ras-dependent Yap1 expression to drive colorectal cancer stemness and development. Mol Carcinog 58(4):500–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.22944

Khorramdelazad H et al (2015) S100A12 and RAGE expression in human bladder transitional cell carcinoma: a role for the ligand/RAGE axis in tumor progression? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(7):2725–2729. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.7.2725

Liu G et al (2013) Expression of beclin 1 in bladder cancer and its clinical significance. Int J Biol Markers 28(1):56–62. https://doi.org/10.5301/JBM.2012.9769

Baspinar S, Bircan S, Yavuz G, Kapucuoglu N (2013) Beclin 1 and bcl-2 expressions in bladder urothelial tumors and their association with clinicopathological parameters. Pathol Res Pract 209(7):418–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2013.04.006

Cai M et al (2014) Beclin 1 expression in ovarian tissues and its effects on ovarian cancer prognosis. IJMS 15(4):5292–5303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15045292

Wu S et al (2015) Expression and clinical significances of beclin1, LC3 and mTOR in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8(4):3882–3891

Shi F, Luo D, Zhou X, Sun Q, Shen P, Wang S (2021) Combined effects of hyperthermia and chemotherapy on the regulate autophagy of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells under a hypoxic microenvironment. Cell Death Discov 7(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-021-00538-5

Yoshihara N, Takagi A, Ueno T, Ikeda S (2014) Inverse correlation between microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 and p62/sequestosome-1 expression in the progression of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol 41(4):311–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.12439

Arani RH, Mohammadpour H, Moosavi MA, Abdollahi A, Rahmati M (2021) Autophagy markers p62, LC3II and beclin1 correlate with clark levels in melanoma tumors. Res Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-727631/v1

Ojha R et al (2014) Inhibition of grade dependent autophagy in urothelial carcinoma increases cell death under nutritional limiting condition and potentiates the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agent. J Urol 191(6):1889–1898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.006

Li T, Jiang D, Wu K (2020) p62 promotes bladder cancer cell growth by activating KEAP1/NRF2-dependent antioxidative response. Cancer Sci 111(4):1156–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14321

Lai W, Kong Q, Chen H, Li X, Li Y, Fang J (2021) Extracellular HMGB1 interacts with RAGE and promotes chemoresistance in acute leukemia cell. Europe PMC. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-349396/v1

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS1 conceived and designed the study. AS2 and SK provided patient sample; AS3 performed experiments, acquired and analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript; SK and NG helped in analyzing data; SK and HK acquired data; RMP performed biostatistical analysis; AS1, AS2, and NG edited the final manuscript. [AS1: Alpana Sharma; AS2: Amlesh Seth; AS3: Aishwarya Singh].

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This research involving human patients and healthy individuals had provided written informed consent. This study has been approved by Institutional Human Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India (IECPG-692/31.01.2018) prior to its commencement.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, A., Gupta, N., Khandakar, H. et al. Autophagy-associated HMGB-1 as a novel potential circulating non-invasive diagnostic marker for detection of Urothelial Carcinoma of Bladder. Mol Cell Biochem 477, 493–505 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-021-04299-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-021-04299-8