Abstract

This paper reports a study of how the benefits that large shareholders derive from their control of a firm affect the equity issue and investment decisions of the firm. I introduce an explicit agency cost structure based on the benefits of control of the largest shareholder. In a simple extension of the model developed by Myers and Majluf (J Financial Econ 13:187–221, 1984), I show that underinvestment is aggravated when there are benefits of being in control and these benefits are diluted if equity is issued to finance an investment project. Using a large panel of US data, I find that the concerns of large shareholders about the dilution of ownership and control cause firms to issue less equity and to invest less than would otherwise be the case. I also find that it makes no significant difference whether new shares are issued to old shareholders or new shareholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The terms “benefits of control” and “private benefits” are used interchangeably in this paper. Private benefits are those benefits where “some value, whatever the source, is not shared among all the shareholders in proportion of the shares owned, but it is enjoyed exclusively by the party in control” (Dyck and Zingales 2004, p. 541).

There has been some recent work on how to separate voting rights from cash flow rights in more subtle ways than, for example, having multiple classes of common stock. See Hu and Black (2007) for more on this decoupling of economic and voting ownership.

Note that a large ownership stake also means that more costs are internalized. In terms of an optimal ownership structure, this indicates a solution similar to the coalition formation effect described by Bennedsen and Wolfenzon (2000), who state that the coalition with the smallest cash flow stake wins because it has the largest group of shareholders to exploit.

Benefits of control could also come from the investment. In that case, z′ could be greater than z, and that would alleviate the underinvestment problem caused by the large shareholder’s concern about dilution of ownership and potential loss of control. In some cases, the underinvestment problem would become an overinvestment problem. For a model in which the large shareholder’s private benefits of control come from the investment opportunity, see Wu and Wang (2005).

The indifference line in the model by Myers and Majluf (1984) is \( b = {\frac{E}{{P^{\prime } }}}a + E\left( {{\frac{S}{{P^{\prime } }}} - 1} \right) \).

Dlugosz et al. (2006) document problems with currently available data, propose a consistent set of solutions to those problems and make a clean database freely available. This can be downloaded from

The ownership database uses the Investor Responsibility Research Center (IRRC) sample as a starting point. This universe covers about 1,300 single-classed firms per year. The IRRC universe is drawn from the Standard & Poor’s 500 as well as the annual lists of the largest firms in the publications of Fortune, Forbes, and BusinessWeek.

Data coverage for equity issuance is much more limited than for investment.

It is not clear where a proper instrument is to be found. I use an instrument based only on the data in hand (suggested in Greene 2003). The instrument is equal to 1 if the potential loss of control is larger than the median value and 0 if the potential loss of control is less than the median.

The choice of Shapley and Shubik (1954) is motivated by the notion of power as the expected relative share of benefits available to the controlling coalition of shareholders (Felsenthal and Machover 1998). It captures the idea that the largest shareholder’s attempt to maintain control by preventing equity issues is unfavorable to other shareholders.

Please see “Appendix 1” for an example of how shareholders’ voting power is calculated.

See Felsenthal and Machover (1998) for more on the monotonicity condition.

In accordance with Schedule 14a of the Security Exchange Act of 1934, the data include insider ownership below 5%. Under Section 12 of the Act, anyone who owns more than 10% of the shares is considered an insider. This consideration is not, however, used in the data.

Rajan and Zingales (1995) adjust debt by subtracting cash and marketable securities from total debt, and equity by adding provisions and deferred taxes and subtracting intangibles. This makes sense in an international comparison, but the adjustments are not necessarily the optimal way to study leverage. For example, accounting differences may be an optimal response to the existing legal environment. I therefore chose to use the raw measures and draw inferences from the basic information provided by accounting data.

Note that managerial discretion (with a view to the manager’s own benefit and not the benefit of the large shareholder as it is modeled in the analytical framework) manifests itself as overinvestment out of cash flows. Jensen (1986) argues that, by imposing a claim on the firm’s cash flow, debt limits the managers’ incentives to engage in non-optimal activities such as overinvestment. Including market leverage as a control variable does not change the results (not reported).

Consistent with the notion that block holdings are fairly stable over time, more than 50% of the year-to-year changes in the largest shareholder’s ownership are less than 10%.

I excluded firm-year observations with a net repurchase of shares. However, a measure of the potential gain of control from an equity decrease could easily be constructed to study the effect of this on the level of repurchase. I leave this to future work.

If the largest shareholder’s ability to dictate the firm’s management fails, managerial discretion becomes an issue to consider. One source of managerial discretion is carelessness in monitoring by shareholders and the market for corporate control. In this situation, the negative coefficient of the largest shareholder’s ownership stake lends support to the conclusion that better incentives to exert effort or better incentives to monitor lead to smaller equity increases. It could be that empire building is prevented this way (Mueller 2008).

With managerial discretion, this could again be an indication that empire building is prevented.

Ibid.

Please see “Appendix 2” for a description of how to estimate marginal q.

References

Alavi, A., Pham, P., & Pham, T. (2008). Pre-IPO ownership structure and its impact on the IPO process. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32, 2361–2375.

Albuquerque, R., & Schroth, E. (2010). Quantifying private benefits of control from a structural model of block trades. Journal of Financial Economics, 96, 33–55.

Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2002). Market timing and capital structure. Journal of Finance, 57, 1–32.

Barclay, M., & Holderness, C. (1989). Private benefits from control of public corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 25, 371–395.

Bebchuk, L. (1999). A rent-protection theory of corporate ownership and control. Harvard Law and Economics. Discussion Paper, 260.

Bennedsen, M., & Wolfenzon, D. (2000). The balance of power in closely held corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 113–139.

Benson, B. W., & Davidson, W. N. (2009). Reexamining the managerial ownership effect on firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance, 15, 575–586.

Cronqvist, H., & Fahlenbrach, R. (2009). Large shareholders and corporate policies. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 3941–3976.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The law and economics of self-dealing. Journal of Financial Economics, 88, 430–465.

Dlugosz, J., Fahlenbrach, R., Gompers, P., & Metrick, A. (2006). Large blocks of stock: Prevalence, size, and measurement. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12, 594–618.

Dyck, A., & Zingales, L. (2004). Private benefits of control: An international comparison. Journal of Finance, 59, 537–600.

Fama, E. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88, 288–307.

Fama, E., & French, K. (2005). Financing decisions: Who issues stock? Journal of Financial Economics, 76, 549–582.

Felsenthal, D., & Machover, M. (1998). The measurement of voting power: Theory and practice, problems and paradoxes. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

Gadhoum, Y., Lang, L., & Young, L. (2005). Who controls US? European Financial Management, 11, 339–363.

Ghosh, A., Moon, D., & Tandon, K. (2007). CEO ownership and discretionary investments. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 34, 819–839.

Greene, W. (2003). Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Guedes, J. C., & Loureiro, G. R. (2002). Are European corporations fleecing minority shareholders? Results from a new empirical approach. Working Paper.

Gugler, K., Mueller, D., & Yurtoglu, B. (2004). Marginal q, Tobin's q, cash flow, and investment. Southern Economic Journal, 70, 512–531.

Gugler, K., Mueller, D., & Yurtoglu, B. (2008). Insider ownership, ownership concentration and investment performance: An international comparison. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14, 688–705.

Gugler, K., & Yurtoglu, B. (2003). Average q, marginal q, and the relation between ownership and performance. Economic Letters, 78, 379–384.

Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (1991). The theory of capital structure. Journal of Finance, 46, 297–355.

Himmelberg, C. P., Hubbard, R. G., & Palia, D. (1999). Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership structure and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 53, 353–384.

Hu, H. T. C., & Black, B. (2007). Hedge funds, insiders, and the decoupling of economic and voting ownership: Empty voting and hidden (Morphable) ownership. Journal of Corporate Finance, 13, 343–367.

Huang, Z., & Xu, X. (2009). Marketability, control, and the pricing of block shares. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33, 88–97.

Jensen, M. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76, 323–329.

Lease, R., McConnell, J., & Mikkelson, W. (1983). The market value of control in public-traded corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 11, 439–471.

Lease, R., McConnell, J., & Mikkelson, W. (1984). The market value of differential voting rights in closely held corporations. Journal of Business, 57, 443–467.

Lemmon, M., & Zender, J. (2009). Debt capacity and tests of capital structure theories. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, forthcoming.

Mueller, E. (2008). Benefits of control, capital structure and company growth. Applied Economics, 40, 2721–2734.

Myers, S. (1977). Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5, 147–175.

Myers, S., & Majluf, N. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13, 187–221.

Nenova, T. (2003). The value of corporate voting rights and control: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 68, 325–351.

Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. Journal of Finance, 50, 1421–1460.

Shapley, L. S., & Shubik, M. (1954). A method for evaluating the distribution of power in a committee system. American Political Science Review, 48, 787–792.

Shyam-Sunder, L., & Myers, S. (1999). Testing static tradeoff against pecking order models of capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 51, 219–244.

Stulz, R. (1988). Managerial control of voting rights: Financing policies and the market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 25–54.

Stulz, R. (1990). Managerial discretion and optimal financing policies. Journal of Financial Economics, 26, 3–27.

Thomsen, S., Pedersen, T., & Kvist, H. K. (2006). Blockholder ownership: Effects on firm value in market and control based governance systems. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12, 246–269.

Welch, I. (2004). Capital structure and stock returns. Journal of Political Economy, 112, 106–131.

Wu, X., & Wang, Z. (2005). Equity financing in a myers-majluf framework with private benefits of control. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11, 915–945.

Zhou, X. (2001). Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance: Comment. Journal of Financial Economics, 62, 559–571.

Zingales, L. (1994). The value of the voting right: A study of the Milan stock exchange experience. Review of Financial Studies, 7, 125–148.

Acknowledgments

Discussions, suggestions, and comments from Annette Vissing-Jorgensen, Tom Berglund, Steen Thomsen, Henri Servaes, Tom Aabo, Johan Eklund, Jan Bartholdy, and Morten Balling are gratefully acknowledged. This work was partly done while visiting Department of Finance at Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University. Their kind hospitality is gratefully acknowledged as well.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1 The concept of voting power

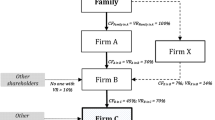

Consider the case where there are three shareholders, A, B and C, who share the voting rights in a firm in the proportions 45, 35, and 20%. It seems unlikely that the distribution of power coincides with the distribution of votes when binary decisions are made by a simple majority. A quick assessment might suggest that shareholder C is the least powerful. However, consider the four possible ways in which a decision can be made. Since it takes a simple majority of the votes to make a decision, shareholder A and B can vote together (80%), shareholder A can vote with shareholder C (65%), shareholder B can vote with shareholder C (55%), or they can vote unanimously (100%). Shareholder C is a member of as many winning coalitions as shareholders A and B. If we consider only the three coalitions without a redundant member, we see that because of the character of this voting system, any two of the shareholders can decide on a proposal. Even though shareholder C has fewer votes, he or she has as much influence over outcomes as the other shareholders. The power index of each shareholder equals 1/3.

Formally, shareholder i’s Shapley and Shubik (1954) power index is

where S is the number of shareholders in the controlling coalition S, and n is the number of shareholders in the firm. The characteristic function ν indicates the value of S in decisions that require a simple majority. We can say that shareholder i is pivotal for a particular sequence if i’s joining the coalition of all shareholders preceding i in the sequence turns this coalition from a non-winning to a winning one. The index can then be interpreted as the proportion among all such sequences (n!) for which shareholder i is pivotal.

Appendix 2 Estimation of marginal q

Since there is no common methodology for the estimation of marginal q, this appendix describes the one used in this paper. I follow Gugler and Yurtoglu (2003). The idea is that I want to know whether additional investment adds value to the firm or not, i.e., whether the firm underinvests or overinvests.

Let the present value of investment I at time t be

q m,t is the return, r t , on the investment relative to the firm’s cost of capital, i t . It is marginal q because it states the change in the market value of the firm relative to the change in the capital stock that caused it. In contrast, average q is the market value of the firm relative to its capital stock.

is then the change in market value from period t − 1 to t where δ t is the depreciation rate for the firm’s total capital. Change in market value is due to changes in assets in place as a result of investment and depreciation. The only variable that is not directly available from data is the depreciation rate.

Assuming that it is constant within industries and over time, I can divide Eq. 9 by M t−1 and run ordinary least squares regressions to estimate separate δ D for each SIC division of industries. With these estimates, I can calculate marginal q for each firm and each year in the following way:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Poulsen, T. Corporate control and underinvestment. J Manag Gov 17, 131–155 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-011-9171-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-011-9171-8