Abstract

Introduction

Foreign-born non-Hispanic Black (NHB) birthing parents are less likely to have a preterm birth (PTB) than US-born NHBs. There is further variation by region and country of origin. We update previous studies by examining PTB rates by nativity, region and country of origin among NHBs in Massachusetts, a state with a heterogeneous population of foreign-born NHBs, including communities excluded from previous studies.

Methods

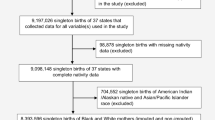

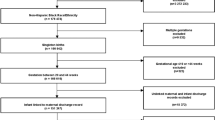

Using 2011–2015 natality data from the three largest metropolitan areas in Massachusetts, we documented associations between nativity, region, and 18 individual countries of origin and PTB, using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for individual-level risk factors.

Results

PTB was highest among US-born NHBs (9.4%) and lowest among those from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (6.6%). Country-specific rates ranged from 4.0% among Angolans to 12.6% among those from Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago. While NHBs from SSA had significantly lower odds of PTB, risk among those from the Caribbean and Brazil was not different from US-born NHBs. The significantly lower risk among foreign-born NHBs and SSAs, in particular, remained robust in adjusted models.

Discussion

Individual-level factors do not explain observed variation among NHB birthing parents. Future research should investigate explanations for lower PTB risk among SSAs, and congruent risk among foreign-born Caribbeans, Brazilians and US-born NHBs. Exposure to racism, a known risk factor for PTB, likely contributes to these inequities in PTB and merits further exploration. Prenatal care providers should assess place of birth among foreign-born NHBs, as well as exposure to racial discrimination among all NLB birthing parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

NA.

Code Availability

NA.

References

Acevedo-Garcia, D., & Bates, L. M. (2008). Latino health paradoxes: Empirical evidence, explanations, future research, and implications. In H. Rodríguez, R. Sáenz, & C. Menjívar (Eds.), Latinas/os in the United States: Changing the face of América (pp. 101–113). Berlin: Springer.

Acevedo-Garcia, D., Sanchez-Vaznaugh, E. V., et al. (2012). Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research: A cross-national framework. Social Science & Medicine, 75(12), 2060–2068.

Acevedo-Garcia, D., Soobader, M. J., et al. (2005). The differential effect of foreign-born status on low birth weight by race/ethnicity and education. Pediatrics, 115, e20–e30.

Alhusen, J., Bower, K., et al. (2016). Racial discrimination and adverse birth outcomes: An integrative review. Journal Midwifery & Women’s Health, 61(6), 707–720.

Almeida, J., Biello, K., et al. (2016). The association between anti-immigrant policies and perceived discrimination among Latinos in the US: A multilevel analysis. Social Science & Medicine-Population Health, 2, 897–903.

Almeida, J., Mulready-Ward, C., et al. (2014). The contribution of social ties and social support to racial/ethnic differences in low birth weight and preterm birth among mothers in New York City, 2004–2007. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 18(1), 90–100.

Anderson, M., Lopez, M. H., et al. (2015). A rising share of the U.S. Black population is foreign-born. Pew Research Center.

Blizzard, B., & Batalova, J. (2019). Brazilian immigrants in the United States. Migration information source. Migration Policy Institute.

Bower, K., Geller, R., et al. (2018). Experiences of racism and preterm birth findings from a Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 2004 through 2012. Women’s Health Issues Journal, 28(6), 495–501.

Bryant, A. S., Worjoloh, A., et al. (2010). Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(4), 335–343.

Burris, H., & Hacker, M. (2017). Birth outcome racial disparities: A result of intersecting social and environmental factors. Seminars in Perinatology, 41(6), 360–366.

Committee on Obstetric Practice, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (2017). Committee Opinion No 700: Methods for estimating the due date. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(5), e150–e154.

Cooper Owens, D., & Fett, S. M. (2019). Black maternal and infant health: Historical legacies of slavery. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1342–1345.

DeSisto, C., Hirai, A., et al. (2018). Deconstructing a disparity: Explaining excess preterm birth among US-born Black women. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(4), 225–230.

DeSisto, C., & McDonald, J. (2018). Variation in birth outcomes by mother’s country of birth among Hispanic women in the United States, 2013. Public Health Reports, 133(3), 318–328.

Elo, I. T., & Culhane, J. F. (2010). Variations in health and health behaviors by nativity among pregnant Black women in Philadelphia. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2185–2192.

Elo, I. T., Vang, Z., et al. (2014). Variation in birth outcomes by mother’s country of birth among non-Hispanic Black women in the United States. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 18(10), 2371–2381.

Frey, H. A., & Klebanoff, M. A. (2016). The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 21(2), 68–73.

Goldenberg, R. L., Culhane, J. F., et al. (2008). Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. The Lancet, 371(9606), 75–84.

Green, T. (2012). Black and immigrant: Exploring the effects of ethnicity and foreign-born status on infant health. Migration Policy Institute.

Hendi, A. S., Mehta, N. K., et al. (2015). Health among Black children by maternal and child nativity. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 703–710.

Klabunde, R. A., Neto, F. L., et al. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of overweight and obesity in Brazilian immigrants in Massachusetts. BMC Public Health, 20(42), 1–9.

Kotelchuck, M. (1994). The adequacy of prenatal care utilization index: Its US distribution and association with low birthweight. American Journal of Public Health, 84(9), 1486–1489.

Krieger, N., Van Wye, G., et al. (2020). Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 10(7), 1046–1053.

Lima, A., Lee, L., et al. (2016). Portuguese speakers in Massachusetts. In Imagine all the people. Boston Redevelopment Authority.

Lu, M., Kotelchuck, M., et al. (2010). Closing the black-white gap in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Ethnicity & Disease, 20(102), S2-S62-76.

Manuck, T. A. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in preterm birth: A complex, multifactorial problem. Seminars in Perinatology, 41(8), 511–518.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., et al. (2019). Births: Final data for 2018. In National vital statistics reports (vol. 63). National Center for Health Statistics.

Mason, S. M., Kaufman, J. S., et al. (2010). Ethnic density and preterm birth in African-, Caribbean, and US-born non-Hispanic black populations in New York City. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(7), 800–808.

Pallotto, E. K., Collins, J. W., et al. (2000). Enigma of maternal race and infant birth weight: A population-based study of US-born Black and Caribbean-born Black women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151(11), 1080–1085.

Parker Dominguez, T., Strong, E. F., et al. (2009). Differences in the self-reported racism experiences of US-born and foreign-born Black pregnant women. Social Science & Medicine, 69(2), 258–265.

Qin, C., & Gould, J. B. (2010). Maternal nativity status and birth outcomes in Asian immigrants. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 12, 798–805.

Reynolds, M. M., Chernenko, A., et al. (2017). Region of origin diversity in immigrant health: Moving beyond the Mexican case. Social Science & Medicine, 166, 102–119.

Sato Conching, K. A., & Thayer, Z. (2019). Biological pathways for historical trauma to affect health: A conceptual model focusing on epigenetic modifications. Social Science & Medicine, 230, 74–82.

Skidmore, T. (2010). Brazil: Five centuries of change. Retrieved January 13, 2020 from https://library.brown.edu/create/fivecenturiesofchange/chapters/chapter-9/brazilians-in-the-u-s/

Sotero, M. M. (2006). A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1(1), 93–108.

Taylor, C. A. L., & Sarathchandra, D. (2016). Migrant selectivity or cultural buffering? Investigating the Black immigrant health advantage in low birth weight. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 18, 390–396.

Funding

We received no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB conceived of the study, conducted the analyses and contributed to writing the paper. MA contributed to writing the paper. JA oversaw analyses and contributed to writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

We received IRB approval from Boston University Medical Center for this study which was deemed exempt.

Consent to Participate

NA.

Consent for Publication

NA.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Belanoff, C., Alade, M.O. & Almeida, J. Preterm Birth Among US and Foreign-Born Non-Hispanic Black Birthing Parents in Massachusetts: Variation by Nativity, Region, and Country of Origin. Matern Child Health J 26, 834–844 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03368-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03368-0