Abstract

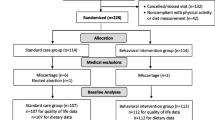

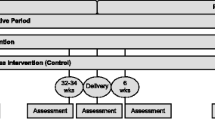

Objectives Beginning life in a healthy uterine environment is essential for future well-being, particularly as it relates to chronic disease risk. Baseline (early pregnancy) demographic, anthropometric (height and weight), psychosocial (depression and perceived stress), and behavioral (diet and exercise) characteristics of rural, Southern, pregnant women enrolled in a maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting program are described. Methods Participants included 82 women early in their second trimester of pregnancy and residing in three Lower Mississippi Delta counties in the United States. Baseline data were collected through direct measurement and surveys. Results Participants were primarily African American (96 %), young (mean age = 23 years), single (93 %), and received Medicaid (92 %). Mean gestational age was 18 weeks, 67 % of participants were overweight or obese before becoming pregnant, and 16 % tested positive for major depression. Participants were sedentary (mean minutes of moderate intensity physical activity/week = 30), had low diet quality (mean Healthy Eating Index-2010 total score = 43 points), with only 38, 4, and 7 % meeting recommendations for saturated fat, fiber, and sodium intakes, respectively. Conclusions for Practice In the Lower Mississippi Delta, there is a need for interventions that are designed to help women achieve optimal GWG by improving their diet quality and increasing the amount of physical activity performed during pregnancy. Researchers also should consider addressing barriers to changing health behaviors during pregnancy that may be unique to this region of the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abu-Saad, K., & Fraser, D. (2010). Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. Epidemiologic Reviews, 32, 5–25. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxq001.

Barker, D. J. P. (1998). Mothers, babies, and health in later life. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., et al. (2012). Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307(5), 491–497. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.39.

Modder J, Fitzsimon K(2010). CMACE/RCOG joint guideline: Managment of women with obesity in pregnancy. London: Centre for Maternity and Child Enquiries/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (CMAC/RCOG).

Wojcicki, J. M. (2011). Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Journal of Women’s Health., 20(3), 341–347. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2248.

Rasmussen, K. M., Dieterich, C. M., Zelek, S. T., et al. (2011). Interventions to increase the duration of breastfeeding in obese mothers: The Bassett Improving Breastfeeding Study. Breastfeeding Medicine., 6(2), 69–75. doi:10.1089/bfm.2010.0014.

Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. (2009). Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

DeVader, S. R., Neeley, H. L., Myles, T. D., et al. (2007). Evaluation of gestational weight gain guidelines for women with normal prepregnancy body mass index. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 110(4), 745–751. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000284451.37882.85.

Hedderson, M. M., Gunderson, E. P., & Ferrara, A. (2010). Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 115(3), 597–604. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cfce4f.

Thorsdottir, I., Torfadottir, J. E., Birgisdottir, B. E., et al. (2002). Weight gain in women of normal weight before pregnancy: Complications in pregnancy or delivery and birth outcome. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 99(5 Pt 1), 799–806.

Morken, N. H., Klungsoyr, K., Magnus, P., et al. (2013). Pre-pregnant body mass index, gestational weight gain and the risk of operative delivery. Acta Obstetrics and Gynecology Scandinavia., 92(7), 809–815. doi:10.1111/aogs.12115.

Viswanathan, M., Siega-Riz, A. M., Moos, M. K., et al. (2008). Outcomes of maternal weight gain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment., 168, 1–223.

Rooney, B. L., & Schauberger, C. W. (2002). Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: One decade later. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 100(2), 245–252.

Christian, L. M. (2012). Physiological reactivity to psychological stress in human pregnancy: Current knowledge and future directions. Progress in Neurobiology, 99(2), 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.07.003.

Field, T., Diego, M., Hernandez-Reif, M., et al. (2009). Depressed pregnant black women have a greater incidence of prematurity and low birthweight outcomes. Infant Behavior and Development., 32(1), 10–16. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.09.005.

Thomson, J. L., Tussing-Humphreys, L. M., & Goodman, M. H. (2014). Delta Healthy Sprouts: A randomized comparative effectiveness trial to promote maternal weight control and reduce childhood obesity in the Mississippi Delta. Contemporary Clinical Trials., 38(1), 82–91. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2014.03.004.

Feskanich, D., Sielaff, B. H., Chong, K., et al. (1989). Computerized collection and analysis of dietary intake information. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 30(1), 47–57.

Harnack, L., Stevens, M., Van Heel, N., et al. (2008). A computer-based approach for assessing dietary supplement use in conjunction with dietary recalls. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 21(Supplement 1), S78–S82. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2007.05.004.

Guenther, P. M., Casavale, K. O., Reedy, J., et al. (2013). Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics., 113(4), 569–580. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016.

Hacker, A. N., Fung, E. B., & King, J. C. (2012). Role of calcium during pregnancy: Maternal and fetal needs. Nutrition Reviews, 70(7), 397–409. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00491.x.

Institute of Medicine. (2013). Dietary reference intakes tables and applications. http://www.iom.edu/Home/Global/News%20Announcements/DRI. Accessed 20 Apr 2015.

Jiang, X., West, A. A., & Caudill, M. A. (2014). Maternal choline supplementation: A nutritional approach for improving offspring health? Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 25(5), 263–273. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2014.02.001.

Qiu, C., Coughlin, K. B., Frederick, I. O., et al. (2008). Dietary fiber intake in early pregnancy and risk of subsequent preeclampsia. American Journal of Hypertension, 21(8), 903–909. doi:10.1038/ajh.2008.209.

Reynolds, C. M., Vickers, M. H., Harrison, C. J., et al. (2014). High fat and/or high salt intake during pregnancy alters maternal meta-inflammation and offspring growth and metabolic profiles. Physiological Reports,. doi:10.14814/phy2.12110.

Chasan-Taber, L., Schmidt, M. D., Roberts, D. E., et al. (2004). Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 36(10), 1750–1760.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

IMG Health Publications. (2015, July). Pregnancy corner. http://www.pregnancycorner.com/pregnant/pregnancy-symptoms/weight-loss.html. Accessed 21 May 2015.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

The Lower Mississippi Delta Nutrition Intervention Research Consortium. (2004). Self-reported health of residents of the Mississippi Delta. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 15(4), 645–662.

United Health Foundation. (2014). America’s Health Rankings. http://www.americashealthrankings.org/states. Accessed 27 Apr 2015.

American College of Sports Medicine. (2006). Impact of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 38(5), 989–1006. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000218147.51025.8a.

Jackson, F. M., Rowley, D. L., & Curry Owens, T. (2012). Contextualized stress, global stress, and depression in well-educated, pregnant, African–American women. Women’s Health Issues, 22(3), e329–e336. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2012.01.003.

Keenan, K., Hipwell, A. E., Bortner, J., et al. (2014). Association between fatty acid supplementation and prenatal stress in African Americans: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 124(6), 1080–1087. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000559.

Acknowledgments

We thank Debra Johnson, Shakari Moore, and Donna Ransome for their research support, and all the participants for giving their time generously to this project. This research is supported by the United States (US) Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service Project 6001-53000-001-00D, and in kind support from the Delta Health Alliance. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomson, J.L., Tussing-Humphreys, L.M., Goodman, M.H. et al. Baseline Demographic, Anthropometric, Psychosocial, and Behavioral Characteristics of Rural, Southern Women in Early Pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 20, 1980–1988 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2016-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2016-y