This is a debate that linguists will never resolve, because it’s partly a matter of taste.

‘If Shakespeare Had Been Able to Google’

The New York Review of Books 55(20) James Gleick

Abstract

Subjective language has attracted substantial attention in the recent literature in formal semantics and philosophy of language (see overviews in MacFarlane in Assessment sensitivity: relative truth and its applications, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014; van Wijnbergen-Huitink, in Meier, and van Wijnbergen-Huitink (eds) Subjective meaning: alternatives to relativism, De Gruyter, Berlin, pp 1–19, 2016; Lasersohn in Subjectivity and perspective in truth-theoretic semantics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017; Vardomskaya in Sources of subjectivity, Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago, IL, 2018; Zakkou in Faultless disagreement: a defense of contextualism in the realm of personal taste, Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt a. M., 2019b). Most current theories argue that Subjective Predicates (SPs), which express matters of opinion, semantically differ from ordinary predicates, which express matters of fact. We will call this view “SP exceptionalism”. This paper addresses SP exceptionalism by scrutinizing the behavior of SPs in attitude reports, which, as we will argue, significantly constrains the space of analytical options and rules out some of the existing theories. As first noticed by Stephenson (Linguist Philos 30(4):487–525, 2007a; Towards a theory of subjective meaning, Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2007b), the most prominent reading of embedded SPs is one where they talk about the attitude holder’s subjective judgment. As is remarked sometimes (Sæbø in Linguist Philos 32(4):327–352, 2009; Pearson in J Semant 30(1):103–154, 2013a), this reading is not the only one: embedded SPs may also talk about someone else’s, non-local, judgment. We concentrate specifically on such cases and show that non-local judgment is possible if and only if SPs are used within a DP that is outside main predicate position and that entire DP is read de re. We demonstrate that the behavior of SPs in attitude reports does not differ from that of ordinary predicates: it follows from general constraints on intersective modification and intensional quantification (Farkas in Szabolcsi (ed) Ways of scope taking, Springer, Dordrecht, pp 183–215, 1997; Musan in On the temporal interpretation of noun phrases, Garland, New York, 1997; Percus in Nat Lang Semant 8(3):173–229, 2000; Keshet in Good intensions: paving two roads to a theory of the de re/de dicto distinction, Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2008). We argue that this unexceptional behavior of SPs in fact has unexpected consequences for SP exceptionalism. Precisely because SPs have been argued to be semantically different from ordinary predicates, not all theories correctly predict these less-studied data: some overgenerate (e.g. Stephenson 2007a, b; Stojanovic in Linguist Philos 30(6):691–706, 2007; Sæbø 2009) and some undergenerate (e.g. McCready in McNally, and Puig-Waldmüller (ed) Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, vol 11, pp 433–447, 2007; Pearson 2013a). Out of the currently available theories, only relativist accounts (Lasersohn in Linguist Philos 28(6):643–686, 2005; MacFarlane 2014; Bylinina in J Semant 34(2), 291–331, 2017; Coppock in Linguist Philos 41(2):125–164, 2018) predict the right interpretation, and only that interpretation. We thus present a novel empirical argument for relativism, and, more generally, formulate a constraint that has to be taken into consideration by any view that advocates SP exceptionalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

Subjective language, which expresses matters of opinion rather than fact, has attracted substantial attention in the recent literature in formal semantics and philosophy of language (see overviews in MacFarlane 2014; van Wijnbergen-Huitink 2016; Lasersohn 2017; Vardomskaya 2018; Zakkou 2019b). In particular, most existing theories argue that there is a semantic difference between (i) ordinary, objective predicates, such as acidic or decidiousFootnote 1 on the one hand, and (ii) Subjective Predicates (SPs), such as adorable or delicious on the other.Footnote 2 We will call this view “SP exceptionalism”.

Ordinary predicates are typically analyzed as semantically dependent on the world of evaluation. The cornerstone of SP exceptionalism is the idea that, in addition to a world, SPs are semantically relativized to a special entity responsible for subjective judgment, or the judge as it has been called since Lasersohn (2005) (we use the term theory-neutrally and discuss different ways of conceptualizing judges in Sect. 2.3). Much of the current discussion about subjective meaning centers on the nature of the judge and on choosing the best implementation of SP exceptionalism based on various special properties exhibited by SPs, in contrast to ordinary predicates, e.g.: disagreement (Lasersohn 2005; Stojanovic 2007; MacFarlane 2014; Zakkou 2019b), retraction (MacFarlane 2014; Zakkou 2019a), embedding under find (Stephenson 2007b; Sæbø 2009; Coppock 2018) or genericity (Anand 2009; Moltmann 2010b, 2012; Pearson 2013a). In this paper, we take a different route.

The empirical focus of the paper is the range of interpretations of SPs in attitude reports (attitudes for short). When embedded SPs occupy main predicate positions, they talk about the attitude holder’s subjective judgment (first noticed in Stephenson 2007a, b). When embedded SPs are within a DP that is outside main predicate position, they also may talk about someone else’s, non-local, judgment (noted in passim in Sæbø 2009; Pearson 2013a) but if and only if that entire DP is read de re. We demonstrate that the behavior of SPs in attitudes does not differ from that of ordinary predicates: it follows from general constraints on intersective modification and intensional quantification (Farkas 1997; Musan 1997; Percus 2000; Keshet 2008). Intersective attributive modifiers cannot be evaluated at a world different from their head noun, which constrains the range of possible interpretations in attitudes for both DPs with ordinary modifiers (a decidious tree) and DPs with subjective modifiers (a delicious tea), but which has not been incorporated into accounts of SP exceptionalism.

The theoretical focus of the paper is a new taxonomy of analytical options for SPs and a novel argument for relativism about subjective meaning. We argue that the unexceptional behavior of SPs in attitudes in fact has unexpected consequences for SP exceptionalism and show that not all theories correctly predict the less-studied data on embedded SPs outside main predicate position: some approaches overgenerate (e.g. Stephenson 2007a, b; Stojanovic 2007; Sæbø 2009) and some undergenerate (e.g. McCready 2007; Pearson 2013a). Out of the currently available theories, only relativist accounts (Lasersohn 2005; MacFarlane 2014; Bylinina 2017; Coppock 2018) predict the right interpretation, and only that interpretation.

Note that the paper is based on conditional reasoning. We do not argue for SP exceptionalism per se. Instead, we assume it with the rest of the literature on the topic and formulate a constraint that has to be taken into consideration by any view that advocates SP exceptionalism. With this caveat in mind, let us proceed to the core empirical observation.

1.2 The central observation

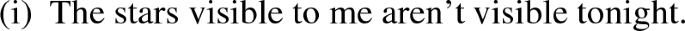

Consider two predicates, depressing and uplifting, both of which intuitively express an opinion rather than fact and thus can be classified as subjective (see Sect. 2.1 on diagnostics for subjectivity). It is well established (Stephenson 2007a; Pearson 2013a) that the judge of an SP embedded under an attitude predicate is most typically interpreted locally, relative to the closest attitude holder (1).

In (1), depressing in the complement clause talks about Mordecai’s subjective judgment, hence the Pascal-oriented uplifting in the follow-up is non-contradictory. However, the reading in (1) is not the only one available for embedded SPs, as they may also talk about someone else’s, non-local, judgment. This is possible when one of the SPs is within a DP that is outside main predicate position in the complement clause, as the uplifting documentary in (2). As the reader can see for themselves, switching the order of predicates would not affect the interpretation.

In (2), the two SPs within the complement clause, uplifting and depressing, are evaluated from different perspectives, that of Pascal and that of Mordecai. If Pascal were to follow (2) with something like and I think so, too, the film is depressing, it would yield a contradiction.

For shortness, we will use the label “outside main predicate position” for SPs such as uplifting in (2). Crucially, it would not be accurate to use the familiar term “attributive position” across the board. First, SPs can be used attributively as part of the main predicate, as in Mordecai believes that the film is an uplifting documentary. Such cases only allow local judgment. Second, SPs can also be used non-attributively in relative clauses within non-main-predicate-position DPs, as in Mordecai believes that the film that is uplifting is depressing. Even though we restrict ourselves to attributive SPs contained within non-main-predicate-position DPs for the rest of the paper, our core argument applies more generally. We predict non-local judgment to be possible for SPs in relative clauses as well, hence the choice of terminology.Footnote 3

The non-local reading in (2) sounds natural. At the same time, other combinations of SPs within one clause result in contradiction: when both are in main predicate position in the complement clause (3a), or when both are in attributive position in the complement clause (3b).

The only way to make (3a) and (3b) non-contradictory would be to evaluate depressing and uplifting from different perspectives, that of Pascal and that of Mordecai (in parallel to 2). However, this mixed reading is not available. The only available interpretation of (3a) is such that both depressing and uplifting are evaluated from Mordecai’s perspective, which results in contradiction. In (3b), the predicates have to be evaluated either each from Pascal’s perspective (3bi) or each from Mordecai’s perspective (3bii), both interpretations yielding a contradiction. Two contrary SPs in a root clause also result in infelicity (4a–4c).Footnote 4

While cases like (2) have not received deep scrutiny, they have been mentioned by Sæbø (2009: 337) and Pearson (2013a: 118, fn.15), both of whom suggest that such cases may involve de re interpretation of the DP containing the SP evaluated with respect to a non-local judge, namely, the uplifting documentary in (2). We will argue in Sect. 3 that such interpretation is possible if and only if the entire DP containing the SP is read de re, as our core case in (5) shows.

(5) can only describe the following situation, corresponding to (5b). Pascal and Mordecai watched a film that is a documentary in the non-local world, that Pascal knows to be a documentary, that he finds uplifting and that Mordecai finds depressing. In other words, (5) is non-contradictory only if the noun documentary is interpreted de re, i.e. with respect to a non-local world, and the SP uplifting is interpreted with respect to a non-local judge, Pascal. (5a) is contradictory for the same reasons as (4): it ascribes contradictory beliefs to one person. The SP is interpreted with respect to a local judge, Mordecai, and there is a contrary predicate in main predicate position (here, depressing), also interpreted with respect to the same judge. The noun here is interpreted de dicto, with respect to one of Mordecai’s belief worlds. This interpretation, with the SP uplifting anchored to a local judge, is allowed with a non-contradictory predicate in main predicate position (Mordecai believes that the uplifting\(_{M}\) documentary is recent).

There could, in principle, be a disagreement between Pascal and Mordecai not only about the emotional—uplifting versus depressing—effect of the film, but also about its nature. For example, it could be that Mordecai believes the movie to be a documentary, and a depressing one at that, while Pascal could think it to be a mockumentary (fictional work presented as a documentary), and an uplifting one. This is the intended meaning of (5d): Mordecai believes that the uplifting mockumentary, which he mistakes for a documentary, is depressing. However, as the infelicity of (5d) demonstrates, the sentence in (5) cannot describe such a situation. We will call interpretations as in (5d) mixed, with the noun interpreted with respect to a non-local world and the SP interpreted with respect to a local judge. (5c) a mirror image of (5d) (a local world for the noun, a non-local judge for the SP) and is likewise ruled out. Note that, unlike the situation with (5a), changing the main predicate from depressing to the non-contradictory recent would not improve the sentence, it would simply make the infelicity less apparent and more contextual support would be required to detect it (see detailed discussion in Sect. 3). As we will argue throughout the paper, the culprit with both (5c) and (5d) is the assignment of worlds and judges within the DP in question.Footnote 5

At first blush, the pattern with SPs is unremarkable as it parallels the behavior of ordinary predicates. Two contrary non-SP predicates can be used in one clause without a contradiction only if one of them occurs outside main predicate position in the complement clause and the DP containing it is read de re, as in (6b). Other combinations result in a contradiction, as in (6a, c, d) and (7a–7e).

(6b) is non-contradictory because the two contrary predicates, deciduous and evergreen, are evaluated with respect to different worlds. Embedded main predicate position items, such as evergreen in (6), must be evaluated with respect to the local world of evaluation introduced by the embedding intensional operator (Farkas 1997; Percus 2000). Items that are outside main predicate position, on the other hand, can be interpreted either de dicto (6a), or de re (6b). Intersective attributive modifiers, such as deciduous in (6), are always interpreted relative to the same world as their head noun (Keshet 2008), which excludes mixed interpretations in (6c, d). When the entire subject DP is read de re, it is interpreted relative to a non-local world, and hence no contradiction ensues. In all other cases, deciduous and evergreen are interpreted relative to the same world, thus leading to a contradiction (6a, 7a–7e).

If SPs like uplifting and depressing had the same semantics as ordinary predicates, then the felicity of (5b), and the infelicity of (5a, c, d) and (4) could have been explained along the same lines as the felicity of (6b) and the infelicity of (6a, c, d) and (7a–7e), respectively. However, as we briefly discussed in Sect. 1.1 and will examine in detail in Sects. 2.3 and 4, the literature overwhelmingly advocates SP exceptionalism: all accounts of SPs agree that a simple-minded objectivist analysis—one where SPs express matters of fact—does not hold water. In particular, it has been argued that SPs differ from ordinary predicates in that their semantics includes reference to a beholder, or a judge, in addition to reference to a world. The central question we address in this paper is how the observation about the unexceptional behavior of SPs in attitudes fits into theories of SP exceptionalism. We argue that any theory of SPs that postulates judges has to obey the judge-index correlation:

The judge-index correlation means that the judge of an SP is constrained by the world of evaluation of the SP, and vice versa. Thus, because main predicate position items have to be evaluated at the local world introduced by the attitude (Farkas 1997; Percus 2000), judges in main predicate position will be constrained similarly to the local world, as shown in (1).Footnote 6 Likewise, having multiple judges within an embedded clause as in (2) and (3) will correspondingly require the two SPs to be evaluated at distinct worlds, which is possible if and only if one SP is outside main predicate position and the DP containing it is read de re, as we will argue is the case in (2), whose logically possible interpretations are enumerated in (5).

The novel observation about the behavior of SPs in attitudes, entirely expected in light of the constraints on the distribution of worlds (Percus 2000) and times (Musan 1997), went previously unnoticed in the literature on SPs. Our goal is to show that not all of the available theories on the market can naturally account for the principle in (8). We categorize the existing accounts into three classes: (i) must associate (e.g. Lasersohn 2005, 2017; Egan 2010; MacFarlane 2005, 2014; Bylinina 2017), (ii) can dissociate (e.g. Stephenson 2007a; Stojanovic 2007; Sæbø 2009), and (iii) must dissociate (e.g. McCready 2007; Pearson 2013a). We argue that only accounts that belong to the first class easily predict the correlation we observe, precisely because they bundle together judges and worlds in indices of evaluation (accounts with no judges at all, such as Anand 2009; Kennedy and Willer 2016; Coppock 2018, also predict our data). The accounts belonging to the second class overgenerate: they allow non-attested mixed readings such that a de dicto noun combines with a non-local judge, as in (5d). Finally, must dissociate theories, such as the account in Pearson (2013a), as well as indexical contextualism more generally, undergenerate as is: they allow de re readings of embedded SPs in conjunction with a scopal view of de re (which is independently problematic), but not with other approaches to de re. As we will show, more elaborated views about the semantics of SPs themselves, such as presuppositions about the relation between an SP judge and the world of evaluation for the SP, do not solve the problematic cases either. Out of the currently available theories, only the relativist approaches to subjective meaning make correct empirical predictions (but not all relativist approaches, as the account in Stephenson 2007a, b doesn’t work). We thus take our data to be a new argument for relativism, which, we want to emphasize, relies on independently motivated constraints.

We proceed as follows. Section 2 provides a background on empirical diagnostics of subjectivity and an overview of analytical options that have been proposed for subjective meaning. In Sect. 3, we turn to the empirical justification for the judge-index correlation. Section 4 deals with implications of the correlation for existing theories and makes a case for the must associate version of relativism. Section 5 concludes.

2 Background

This paper is about theories of subjective meaning and how they can (or cannot) handle the behavior of SPs in attitudes. In this section we start by presenting the types of data that motivated theories of SP exceptionalism in the first place and the introduction of judges into semantics. We then briefly discuss a special type of subjective expressions, predicates of personal taste, and conclude with an operational classification of approaches to SPs with respect to the distribution of judges and worlds.

2.1 Diagnosing subjectivity

How should we distinguish between subjective predicates, which express matters of opinion, and objective predicates, which express matters of fact? We will rely on the following two diagnostics of subjectivity: faultless disagreement and embedding under find (see discussion and references in Kennedy 2013; Bylinina 2017; Coppock 2018).

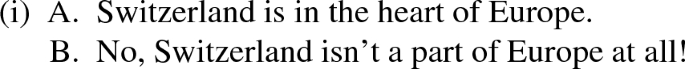

The first test is Faultless Disagreement (Kölbel 2004 and much later work; see recent discussions in MacFarlane 2014: 118–137; Zakkou 2019b). A conversational exchange in (9) is about matters of fact. Only one of the interlocutors can be right as the property of being evergreen reflects the objective state of affairs and a tree cannot be both evergreen and deciduous at the same time.

An exchange in (10), on the other hand, is different. It is about matters of opinion. Both interlocutors can be right insofar as each of them is giving a subjective judgment.

The term faultless disagreement refers precisely to situations like the one in (10) as none of the parties is at fault: an object can be considered elegant by one party while being considered not elegant by another at the same time. The contrast between (9) and (10) is due to the difference between evergreen and elegant: the former is an ordinary predicate while the latter is a subjective predicate. All other SPs we discuss in this paper pass this test as well.Footnote 7

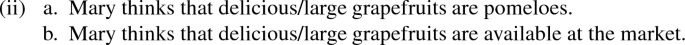

The second test is embedding under find. The so-called subjective attitudes, such as English find and its counterparts in other languages, only take subjective complements, in contrast to neutral doxastics such as think (Stephenson 2007b; Sæbø 2009; Bouchard 2012; Kennedy and Willer 2016; Coppock 2018).

As the contrast in (11) shows, find (11a), but not think (11b), is sensitive to the subjective/objective divide and only allows complements that are matters of opinion, such as elegant. One could speculate that the contrast in (11) is in some way syntactic, as English subjective find only takes small clauses (unlike its discovery counterpart that also takes full clauses; Vardomskaya 2018). However, the contrast is easily replicated in other languages where subjective attitudes allow full clauses but only those that talk about subjective matters, e.g. French trouver (Bouchard 2012), German finden (Reis 2013), Norwegian synes (Sæbø 2009) or Swedish tycka (Coppock 2018).

Complements of find-verbs across languages allow only those expressions that give rise to faultless disagreement,Footnote 8 and in those languages where such verbs take full clauses, they can embed a variety of subjective expressions, such as appearance claims with looks like (independently argued to express matters of opinion; Rudolph 2020) or normative claims with should (see discussion in Sæbø 2009; Reis 2013; Coppock 2018). The primary focus of this paper is English, and all predicates that we classify as subjective, e.g. depressing and uplifting from Sect. 1.2, pass this test.

To sum up, subjective predicates give rise to faultless disagreement and can be embedded under find. Such linguistic behavior differentiates subjective predicates from ordinary predicates and has motivated theories of SP exceptionalism most of which argue that there is a semantic procedure, for any given expression, to tell whether it is subjective or objective. In particular, it has been argued that the beholder of an opinion expressed by SPs has to be referenced in their semantics, an approach we will call judge-dependence. The central claim of this paper concerns a restriction on the interpretation of SPs in attitudes that has nothing to do with their subjectivity but, as we will argue, it has to be taken into account in all theories of SP exceptionalism to avoid incorrect predictions.

2.2 Matters of taste

Starting with Lasersohn (2005), much of the research on subjective language has been focusing on one class, the so-called predicates of personal taste (PPTs). Textbook PPTs, such as fun, tasty and delicious, pass both of our tests, as the possibility of faultless disagreement (12) and of embedding under find (13) illustrate for delicious.

Philosophical literature often distinguishes between judgment about personal taste and, for example, aesthetic judgment, the latter playing an important role in debates on the subjective vs. objective nature of beauty (see discussion and references in Young 2017; Zangwill 2019). From the linguistic standpoint, however, both delicious—a taste predicate—and elegant—an aesthetic predicate—exhibit hallmarks of subjectivity, as our examples (10)–(13) demonstrate (though see Liao et al. 2016; McNally and Stojanovic 2017 on peculiarities of the linguistic behavior of aesthetic adjectives). To this end, it has been argued that all predicates expressing different types of value judgment—culinary, aesthetic, moral, normative—can be classified as subjective in the same way as delicious (Kölbel 2004; Anand 2009; Coppock 2018; Franzén 2018).

Linguistic literature often makes a distinction between (a) genuine PPTs, and (b) predicates that we will label “non-PPT SPs” (sometimes called “evaluative” in the literature), such as, for example, authentic, lazy, mediocre, smart, unethical (Bierwisch 1989; Kennedy 2013; Bylinina 2017; Solt 2018). As discussed in the literature, both types of expressions satisfy our tests, illustrated for mediocre by the possibility of faultless disagreement (14) and of embedding under find (15).Footnote 10

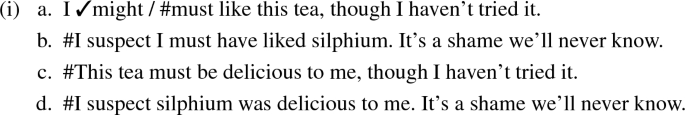

In general, ferreting out which expressions are linguistic PPTs is an involved affair due to the lack of consistent diagnostics of PPT-hood, as opposed to general diagnostics of subjective meaning discussed in the previous section. It is often claimed (Bylinina 2017; Kaiser and Lee 2017, 2018) that only genuine PPTs semantically make reference to an experience (cf. also purely experiential approaches to PPTs in Gunlogson and Carlson 2016; Charlow 2019; Muñoz 2019). Thus, textbook PPTs (16a), unlike many non-PPT subjective predicates (16b), can express the judge overtly with a prepositional phrase that has been analyzed as an experiencer argument of the PPT (see discussion in Sect. 3.3).

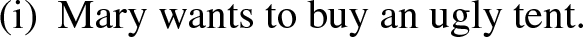

However, the characterization of PPTs, and only PPTs, as allowing overt judges is not uncontroversial (McNally and Stojanovic 2017). For example, ugly, often classified as a non-PPT SP (Bierwisch 1989 and later work), also takes judge PPs (17).Footnote 11

Crucially, delineating the natural class of PPTs and understanding finer-grained distinctions within the realm of subjective predicates aren’t tasks relevant for us here for the following reasons. First, subjectivity has been argued to be semantically hard-wired both for PPTs and non-PPT SPs (Kennedy 2013; Bylinina 2017; Solt 2018), which fits squarely with approaches that advocate a unified semantic analysis for all complements of find (Stephenson 2007b; Sæbø 2009; Bouchard 2012; Coppock 2018).

Second, this paper zooms in on an unexceptional aspect of SPs. We demonstrate that SPs behave in attitudes precisely like ordinary predicates and that this behavior is only problematic in light of the widely postulated SP exceptionalism. To this end, we predict that our central claim about (2) can be replicated with non-PPT SPs as well. As the data below show, the prediction is borne out.

Examples with various combinations of SPs in (18)–(20) mirror the pattern we observed with depressing and uplifting in (2) and ordinary predicates in (6, 7): a non-local perspective is available only to non-PPT SPs that occur outside main predicate position (18a–b, 19a–b, 20a).

As we will show in Sect. 3, a non-local judge for an SP is possible if and only if the entire DP containing it is read de re. We will argue in detail in Sect. 4 that the pattern follows from the judge-index correlation in (8), a general constraint that links the distribution of judges to the distribution of worlds. And if there were no judges in semantics, then there would be no need to postulate this constraint, as the relevant data would be predicted by constraints on worlds and intersective modification alone (Percus 2000; Keshet 2008). As such, the pattern is not affected by (a) the predicate itself being a PPT (2) or a non-PPT SP (18)–(20), or by (b) the predicate in question being contrasted to another SP (2, 18, 19) or to an ordinary predicate (20). In what follows, the distinction between PPTs and non-PPT SPs will not play a role and we will refer to both types of predicate as subjective (although we will talk about overt judges with predicates that allow them in Sect. 3.3, as there are theories that make incorrect predictions for such cases).

Before we move on to theories of SP exceptionalism, a brief comment on the data we consider in this paper is in order. In addition to SPs proper, English find can embed ordinary non-subjective gradable predicates in the comparative (Solt 2018) or with degree modifiers (Bylinina 2017). (21) below illustrates the contrast in the acceptability of pink under find in its positive form (21a) vs. modified by a degree operator (21b).

Find also takes epistemic modal adjectives (Korotkova and Anand forth.), illustrated in (22) for likely:

Both degree constructions (Bylinina 2017; Solt 2018) and epistemic modals (Egan et al. 2005; Stephenson 2007a, b; MacFarlane 2014) have been argued to be subjective and judge-dependent, so those data corroborate our use of tests for subjectivity. However, we will not consider such data in the main body of the paper for the sake of simplicity of representation.

Degree operators (Heim 2000) and modals are intensional: they shift the world of evaluation of their prejacent. What is a likely cause of migraines in a world may turn out not be a cause of migraines in the same world (such modifiers belong to the class of non-intersective non-subsective predicates; Morzycki 2016). At the same time, many theories of subjective meaning that we discuss in this paper are based exclusively on intersective non-intensional predicates like delicious and depressing: the meaning of delicious food is, roughly, an intersection of delicious things in a world and things that are food in the same world.Footnote 14

We suspect that our core generalization about the distribution of judges and worlds also applies to intensional predicates, but leave a thorough discussion of the semantic composition of such cases for future work. We thus concentrate only on non-intensional subjective predicates and will come back to a brief discussion of epistemic modals in Sect. 5.

2.3 Preview of the theoretical landscape

The central empirical observation of this paper is that SPs behave like ordinary predicates in attitudes: they allow non-local readings only when outside main predicate position and when the DP containing them is read de re. The central theoretical observation is that, in light of the widely accepted SP exceptionalism, additional constraints on the theory must be put in place in order to account for the empirical observation. In this section, we give an operational classification of current theories of subjective meaning with respect to our data. The discussion here will be rather informal, to give the reader a taste of different implementations of SP exceptionalism. We fully spell out our semantic assumptions and work out the details of different approaches, along with derivations of relevant examples, in Sect. 4.

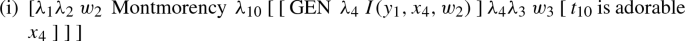

We will use an extensional system in which indices are present at the logical form. We will assume that all non-logical predicates require an argument of type I (the precise nature of this type will be elaborated on in Sect. 4). The interpretation function is relativized to two parameters, a context c and an assignment function g. The context parameter is a tuple that specifies the context of utterance, such as the author, the world etc. \(c = \langle \ speaker,\ world\ \ldots \rangle \). The index is a tuple that specifies the circumstances of evaluation, and minimally includes a world \(i= \langle \ w\ \rangle \) (we will ignore times in this paper for the sake of exposition). In unmodified matrix clauses, the world of the context and the world of the index are identical. The index is shifted by attitude verbs and other intensional operators. Let us illustrate (glossing over many compositional details, such as predicate modification and the interpretation of definite determiners).

Attitude verbs create a new intensional domain (23b) and any world-sensitive expression in their scope will be evaluated with respect to that domain. Thus, in (24) evergreen in the scope of believe gets interpreted with respect to belief worlds rather than the matrix world.

Let us now consider examples with contrary objective predicates within one clause, as in (25).

As discussed in Percus (2000), only non-main predicate position items, such as the decidious tree in (25) can have two interpretations under attitudes, de dicto (25a) and de re (25b). The de dicto reading is such that the predicate is interpreted with respect to its local intensional domain, and it is infelicitous for (25): it commits Mordecai to contradictory beliefs about the tree being both deciduous and evergreen. The de re reading insulates the predicate in question from the closest intensional operator, and allows it to be interpreted with respect to a non-local intensional domain (we discuss mechanisms of such readings in Sect. 4 and in the Appendix). Thus, it is the only reading attested for (25) as it makes it possible to use deciduous and evergreen in one clause without a contradiction. Mixed interpretations such that decidious and tree are interpreted at different worlds (6c, d) are ruled out because items within the same DP have to be interpreted with respect to the same index (Keshet 2008). The same constraint also excludes two contrary predicates within the same DP (#the deciduous and evergreen tree), regardless of its syntactic position.

Let us now turn to our core cases where two contrary SPs occur within one embedded clause without a contradiction. Consider (26).

As discussed in Sect. 1.2, the only felicitous reading of (26) is such that uplifting is evaluated with respect to Pascal’s perspective and depressing from Mordecai’s (26b), otherwise Mordecai is being attributed contradictory beliefs (26a). As we will argue in Sect. 3, this reading becomes available when the entire DP the uplifting documentary is read de re. This situation in (26) is parallel to the situation with ordinary predicates in (25). If depressing and uplifting were ordinary predicates with uncomplicated lexical entries along the lines of (27), the pattern would be amenable to the same explanation as we sketched above for (25).

But neither depressing nor uplifting are ordinary predicates. As we discussed in Sect. 2.1, the linguistic behavior of subjective predicates across the board differs from that of ordinary predicates, which in turn led to theories of SP exceptionalism and the postulating of judges in the semantics of SPs. As it turns out, SP exceptionalism isn’t always equipped to deal with unexceptional aspects of the behavior of SPs. In the remainder of this section, we group theories of SP exceptionalism into three families based on how they handle our core data. We will show that, even though the pattern we discuss is itself not surprising, it creates problems for several types of approach to subjective meaning.

The crucial property that differentiates SPs from ordinary predicates is that they express an opinion, and most theories of SP exceptionalism incorporate the individual whose opinion is being expressed in the semantics of SPs as a judge. To this end, there are proposals that treat judges as, for example, implicit arguments (Bhatt and Izvorksi 1998), evaluative coordinates (Lasersohn 2005, 2017; Stephenson 2007a, b; MacFarlane 2014; Bylinina 2017), or special anaphors (Stojanovic 2007; Sæbø 2009; Moltmann 2012; Pearson 2013a).

It is now common to divide the diverse landscape of contemporary PPT theories into two major camps based on how the judge is fixed, contextualism and relativism (see MacFarlane 2014; Coppock 2018 for a recent discussion). Simplifying matters, the judge is determined by the context of utterance in a contextualist framework (Stojanovic 2007; Glanzberg 2007; Anand 2009; Moltmann 2010b; Schaffer 2011; Pearson 2013a; Zakkou 2019b) and by the circumstances of evaluation in a relativist framework (Lasersohn 2005, 2017; Stephenson 2007a, b; Egan 2010; MacFarlane 2014; Bylinina 2017). We will show that only relativist accounts (but not all of them) derive our generalization and take this to be a novel argument for relativism.Footnote 15 Based on the behavior of SPs in attitudes, we formulate the judge-index correlation (28).

We argue that any theory of SP exceptionalism that postulates judges, whether those are part of the context of utterance or the circumstances of evaluation, has to obey this constraint. For our purposes, the accounts of SPs fall into three classes: (i) must associate theories, which bundle together judges and worlds in indices of evaluation, (ii) can dissociate theories, which do not have a strict link between the distribution of judges and that of worlds, and (iii) must dissociate theories, in which judges for an SP are fully independent of the world of evaluation of the SP. In Sect. 4, we will demonstrate that only theories in the first group in fact obey the judge-index correlation. Below, we provide a preview of how those different options work. In all of those theories, subjective predicates have a judge argument in their semantics and the differences stem from the compositional source of judges.

MUST ASSOCIATE theories include the judge of SPs into the index of evaluation  (Lasersohn 2005, 2017; MacFarlane 2014). A simplified lexical entry for the SP depressing is given below in (29).

(Lasersohn 2005, 2017; MacFarlane 2014). A simplified lexical entry for the SP depressing is given below in (29).

(30) schematically shows how the de re interpretation of our core example is derived in this type of framework.

Main predicate position items are always evaluated in the local intensional domain, so depressing is relativized to the index \(i'\) introduced by the attitude. Because judges are part of the index, depressing is also relativized to the local judge judge(\(i'\)), which is by default the attitude holder, Mordecai. The mechanism responsible for de re makes uplifting relativized to the non-local index i. Again, because the judge for uplifting will be part of the same index, uplifting will be anchored to the non-local judge judge(i). In matrix clauses, the judge is by default anchored to the speaker, so uplifting is Pascal-oriented in (30). The de dicto reading in (31) is derived in the same way, except that both depressing and uplifting will be relativized to the same judge of the same index, which results in contradiction.

Crucially, because the distribution of judges is intrinsically connected to the distribution of worlds, must associate theories derive all, and only, interpretations that are available for embedded SPs. We discuss this type of approach in Sect. 4.2.

CAN DISSOCIATE theories are similar to the must associate ones in that judges are part of the index of evaluation but the overall semantics of SPs is more flexible (Stephenson 2007a, b; Stojanovic 2007; Sæbø 2009). The opinion holder can be directly referential to the judge coordinate of the index (29) or it can be a free variable (32):

In this type of framework, the derivation for the de re reading of our core cases and the contradictory de dicto reading proceeds in the same way as in (30) and (31), respectively. However, can dissociate theories overgenerate and predict an unattested mixed interpretation for embedded SPs. Because SPs can be anchored to a free variable, it is predicted that the judge of an SP outside main predicate position can be anchored to a non-local judge even if the entire DP containing the SP is read de dicto (33).

As we discuss in detail in Sect. 4.3, the reading in (33) is a major problem for can dissociate theories, as it isn’t attested for SPs nor intersective modifiers more generally.

MUST DISSOCIATE theories instantiate various forms of indexical contextualism (McCready 2007; Schaffer 2011; Pearson 2013a; Bylinina et al. 2014; Zakkou 2019b). The crucial difference from theories we have introduced so far is that the judge in this type of framework is a dedicated coordinate of the context of utterance  , rather than the index, as (34) illustrates.

, rather than the index, as (34) illustrates.

A system like (34) makes no explicit connection between SP judges, provided by the context, and SP worlds, provided by the index. The interpretation of SPs is straightforward in root clauses because, as we discussed earlier, the world of the index and the world of the context are the same in such cases. However, this very move creates compositional problems for the interpretation of SPs in attitudes. Expressions that get their value entirely from context normally remain intact in the scope of intensional operators, as such operators only manipulate the index and not the context. Therefore, we end up with a situation such that an embedded SP is evaluated with respect to a non-local judge and a local world, which we argue to be impossible. There are mechanisms to shift the context as well, from c to \(c'\), and they unproblematically derive the contradictory de dicto reading of our core cases. However, even with those mechanisms in place deriving the de re interpretation of an SP is only possible under the Scope Theory of de re (Russell 1905), namely, when the entire DP is interpreted outside the scope of the attitude at LF (35).

Mechanisms responsible for de re did not matter for our discussion so far, but in fact scopal theories of de re have been proven to be independently problematic (see discussion in Charlow and Sharvit 2014; Keshet and Schwarz 2019). To this end, because must dissociate theories must be coupled with a scopal view on de re in order to capture our data, they ultimately do not derive our generalization in a satisfying way. In Sect. 4.4, we discuss in detail two approaches of this type, an indexical contextualist view along the lines of (34) and a more sophisticated version in Pearson (2013a). We show that each of them undergenerates, and surmise that any contextualist version of SP exceptionalism will have the same problem. In the Appendix, we further substantiate this claim by looking at the judge-index correlation in the concept generators framework (Percus and Sauerland 2003), which is one of the standard mechanisms for de re.

We thus conclude the overview of our argument. We have shown that SPs are linguistically different from ordinary predicates and have given an overview of analytical options with respect to the judge-index correlation. We have briefly demonstrated that only must associate theories (or, for that matter, theories that have no judges at all) unproblematically handle our data and obey the generalization. All other theories face problems, either by overgenerating, as is the case for can disssociate theories, or by undergenerating, as is the case for must dissociate theories. Before considering such issues in detail, however, we need to demonstrate that multi-judge sentences indeed allow multiple judges—but only if the embedded subject is read de re. In the next section, we turn to the empirical heart of the paper and provide extensive justification for the judge-index correlation across linguistic environments.

3 The empirical generalization

This section provides factual evidence for the central empirical claim of the paper, the judge-index correlation. Here is how our examples are structured.

First, we have been tacitly assuming that judges are atomic individuals. The literature suggests that they may be non-atomic entities (Lasersohn 2005), that they may be generic (Bhatt and Izvorksi 1998; Moltmann 2010a; Pearson 2013a), or that judges as individuals (or groups of individuals) should be altogether replaced with standards of taste (MacFarlane 2014; Coppock 2018). Here, we confine ourselves to scenarios with two distinct atomic individuals whose opinions are salient.

Second, it has been argued that SPs with different judges can be predicated of the same entity, provided that the SPs in question describe different dimensions of a given object and are thus relatively non-contrary (Anand 2009). In (36) below, delicious and well-packed reflect the cat’s and the speaker’s judgment, respectively:Footnote 16

In order to avoid this potential confound, in what follows we will only consider relatively contrary PPTs, such as uplifting and depressing in Sect. 1.Footnote 17

Third, we will also focus on simple sentences of the form schematized in (37) below, where the clause of interest contains a copular clause with a single nominal phrase subject. We will call that single nominal the subject and the main predicate of that clause mainPred. This template is meant to include attributive SPs within the subject as well as SPs inside relative clauses. However, as we stated in Sect. 1, we will only focus on attributive uses.

Finally, alongside our discussion surrounding the semantics for attitude predicates, we want to ensure initially that we are dealing with ‘reported autocentric’ cases, where the attitude holder serves as the local judge. We will thus construct contexts where the attitude holder’s perspective is relevant (to the attitude holder). We will revisit this simplifying assumption in Sect. 3.4.

3.1 The claim

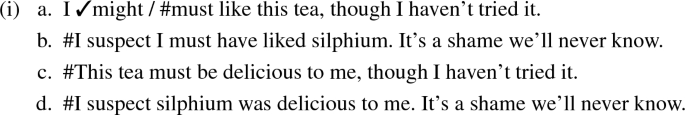

The central empirical question is what construals of the subject are allowed in multi-judge environments. We will show below that only de re construals are possible (de dicto is possible but contradictory). One suggestive piece of evidence for this claim emerges when we examine who is committed to the documentary being uplifting for Pascal in (38). Intuitively, for this sentence to be sensible, Pascal must himself be committing to finding the documentary uplifting: fixing the judge of the subject SP uplifting as the speaker (=Pascal) would also fix the world of evaluation for the SP to the actual world.

We can sharpen this intuition by constructing cases where the status of other predicates in the subject nominal may differ between the speaker and the attitude holder. Consider a case where two friends are together choosing stuffed animals from a catalog. Again, they may differ both on their evaluation of the aesthetics of a toy as well as in what kind of toy it is, e.g. a dog or a fox. As in the case of (38), the judge of the subject SP adorable correlates with the choice of nominal. Fixing the speaker as the judge of adorable is only possible in concert with dog, the correct nominal in the actual world (39a) and impossible with fox, the de dicto nominal (39b).Footnote 18

Turning now to cases where Mary forms a mistaken belief about Sue’s opinion on a toy, consider a scenario where Mary incorrectly takes Sue to think the toy is both a dog and adorable while Sue actually thinks that the toy is a dog and average. Mary herself thinks the toy is an ugly fox. In such a scenario, Sue can report that Mary thinks a fox (de dicto) (40a) is ugly or a dog (de re) is ugly (40b). However, adding the SP adorable in the subject with Sue as the judge renders the sentence infelicitous, regardless of the nominal being de dicto (40c) or de re (40d), because adorable isn’t how Sue characterizes the object in question. Adding the SP average to the de re nominal, on the other hand, is fine, as it reflects Sue’s actual opinion (40e).

Let us dwell on this for a moment. By scenario design, adorable with Sue as the judge forces a de dicto interpretation of the SP, because Sue herself does not consider the toy adorable. In principle, this could still be compatible with a relatively contrary SP in mainPred position, since that will likely be interpreted with the attitude holder as the judge. However, the sentence is infelicitous regardless of the nominal chosen (40c, d), even with the relatively uncontroversial toy in (41) below.

The pattern in (40) and (41) is in line with the behavior of intersective nominal modifiers in general (Keshet 2008). As we have already seen in Sect. 1.2 with ordinary predicates like evergreen (6, 7), an embedded clause with two contrary predicates is sensible only if those two predicates occupy different syntactic positions. Crucially, when one contrary predicate is in mainPred position, it forces the entire subject nominal to be evaluated relative to the matrix world of evaluation. Thus, the only sensible interpretation of (42) requires the speaker to commit to there being baby Martians:Footnote 19

Given these facts, it is thus unsurprising that in cases where the subject SP is evaluated in the matrix world we observed that the subject nominal predicate must be as well (39). What is important, however, is that using relatively contrary SPs in the subject and mainPred positions behaves like choosing contrary predicates (40c, d). The fact that SPs are judge-dependent does not provide a way out of contradiction: it is not possible to evaluate an SP at a world different from the world of its head noun, which, again, follows the pattern with intersective modifiers, which disallow mixed readings such that the modifier is evaluated at one world and the noun at another.

Let us recap what the data in (38)–(41) suggest. We asked whether we have evidence that the subject nominal must be read de re in sentences like (37) when the two SPs differ in their intended judges. To help fix things, we limited ourselves to cases where the two SPs were relatively contrary, which would force multiple judges. We considered two cases where the covert judge of the subject SP was linked to the speaker. In the first, where the world of evaluation for the SP was linked to the actual world, the rest of the subject descriptive content was forced to be read de re, i.e. it was forced to also be evaluated in the actual world (39a). When the world of evaluation for the SP was linked to the doxastic alternatives of the attitude holder, multiple judges were simply not possible (40c, d). This is, however, a reading that can dissociate theories predict to be possible, a fact that we mentioned in Sect. 2.3 and that we discuss in detail in Sect. 4.3.

In the next section we go over several environments that have been argued in the literature to empirically block de re construals. We show that, indeed, in such environments multi-judge instances of the schema in (37) are ungrammatical, and thus provide more evidence for our central claim without relying on complex scenarios presented in this section.

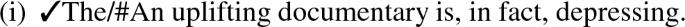

3.2 De re blocking environments

Research on constructions that require identity of intensional parameters identifies a number of empirical tests that diagnose de re readings. We are going to use them to further support the central empirical claim of the paper: for a judge to be non-local, the DP containing it must be interpreted de re. Specifically, we show below that multi-judge cases are impossible in environments independently known to be allergic to de re.

Free Indirect Discourse (FID) FID is a narrative technique that reports speech and thoughts of the main protagonist (Banfield 1982; see recent discussion in Eckardt 2014). Unlike ordinary quotation, FID preserves the narrator’s perspective when talking about tense and personal indexicals, which in the respective literature is typically taken as evidence of its hybrid status (though see Maier 2015 for a quotational analysis of FID). We concentrate on the property that direct discourse and FID share (noticed already in Banfield 1982, see discussion in Sharvit 2008): a block on de re interpretations. As (43) shows, a definite description in an FID environment can only be read de dicto. If John thinks that the dean is the president, then this person must be referenced by the definite in FID. The same is true with names and pronominal gender.

The behavior of FID is in contrast with bona fide indirect discourse, which allows both de dicto (a) and de re readings (b).

Thus, FID serves as a simple test for multi-judge sentences. If the subjects of such sentences are obligatorily interpreted de re, then they should be contradictory in FID environments, regardless of the scenario. This is precisely what we find. When we embed versions of (2) and (39) in FID, they are ungrammatical, as shown in (45a, 45c).

Existential there Building off observations by Musan (1997), Keshet (2008) identifies the existential there construction as an environment where nominals must be interpreted de dicto. In other words, both the pivot and coda must be evaluated against the world introduced by the modal operator. Thus, assuming that professor and in college are contrary, yoking the two together in the existential engenders a contradiction (46a), while making a copular claim does not (46b).

Testing the behavior of SPs in this environment is less straightforward than in the case of FID. As shown by Milsark (1979), there codas classically permit only stage-level predicates (ones that describe temporary properties) and ban individual-level predicates (ones that describe more permanent properties; terminology and distinction from Carlson 1980):

Unfortunately, we cannot construct existential there sentences containing relatively contrary SPs across the pivot and coda, as all of the subjective predicates we have tested are ungrammatical in the coda of a there existentials to begin with (38).

On the basis of similar distributional restrictions, Pearson (2013a) argues that textbook PPTs (of the type discussed in Sect. 2.2) are individual-level predicates. The ungrammaticality of examples like (38) suggests that all subjective predicates are,Footnote 20 though an anonymous reviewer reminds us that there codas exclude some stage-level predicates as well (Jäger 2001).

Regardless of the ultimate explanation, this means that we cannot consider cases with two relatively contrary SPs, but must consider again the appropriateness of a sentence in a specific scenario where the de dicto reading of the relevant nominal would be false. Consider the scenario below, where Mary speculates that Sue would like a stuffed dog Mary saw in a catalog (and Mary herself hated). In such a case, it is only felicitous to use ugly in an existential pivot, but not adorable (49).

Have Have constructions constitute yet another environment that blocks de re readings (Keshet 2008). In those constructions, both the nominal and the predicate following it should be interpreted with respect to the same world, which forces the nominal to be read de dicto under intensional operators and leads to a contradiction in case of two opposite predicates in one clause (50a). With a regular copular construction, the DP can be read de re and no contradiction ensues (50b).

Similarly to the existential there construction, testing SPs in this environment is tricky as the post-nominal clauses of have constructions only permit stage-level predicates (51a) and ban individual-level predicates (51b):

Given the restriction above, we can only use SPs in the nominal argument of have but not in the post-nominal clause. In (52) below (modeled in the same way as 49), the DP cannot contain the SP adorable if it is meant to be read de re and reflect Sue’s perspective.

Let us take stock again. We have considered three environments that have been argued in the literature to grammatically disallow de re readings for nominals: Free Indirect Discourse, existential there pivots, and the nominal complements of have constructions.Footnote 21 In FID, we find that multi-judge sentences with relatively contrary SPs are incoherent, as would be expected if felicitous uses of such cases force a de re interpretation of the nominal containing the SP. In the case of the existential pivots and have nominals, independent restrictions prevented us from pitting two relatively contrary SPs against each other. However, we found that when the attitude holder has a judgment contrary to that expressed by the SP, such sentences were infelicitous, even if the context provided support for the speaker having the SP judgment in the world introduced by the intensional operator. Thus, a de dicto interpretation of the nominal also forces a ‘local’ SP judge, namely, the attitude holder. If stage-level subjective predicates exist and are allowed in there codas, we predict that putting two such contrary predicates together inside a there construction, one as a coda and one as a pivot, would lead to a contradiction along the lines of (46a). The same prediction holds for have constructions.

To summarize these results, what we see is that the world of evaluation and the judge of the PPT correspond: a local world of evaluation requires a local PPT judge and a long-distance world requires a long-distance judge. In other words, we observe the judge-index correlation, which we stated in (8): the judge of an SP correlates with the index of evaluation for the SP.

3.3 Overt judges

There is one important caveat to our discussion above. Alongside what we might call bare uses, many SP adjectives in English permit overt judges, prepositional phrases like to/for that make the judge of the SP explicit, as in (53) below (like elsewhere in the paper, we use the term judge in a theory-neutral way and do not commit ourselves to any particular analysis of such PPs).

The ability of some SPs to have overt judges is widely discussed in the literature on implicit arguments (Partee 1984; Bhatt and Pancheva 2006). It is often taken to be one of the definitional characteristics of PPTs as opposed to other subjective predicates (Schaffer 2011; Pearson 2013a; Bylinina 2017; though see McNally and Stojanovic 2017) and can be treated as evidence that all uses of genuine PPTs have an experiencer argument in their semantics (cf. Glanzberg 2007; Bylinina 2017). As we stated in Sect. 2.2 when we first mentioned overt judges, potential distinctions within subjective predicates are not central in this paper and we remain agnostic about their argument structure. Of importance for us is the difference in behavior between covert vs. overt judges for those predicates that allow them (which itself is a matter of controversy, as there seems to be inter-speaker as well as cross-linguistic variation; Bylinina 2017).

As we show below, overt judges differ from covert judges with respect to our cases. Specifically, overt judges do not have to be anchored to the attitude holder even in main predicate position, as in (54).

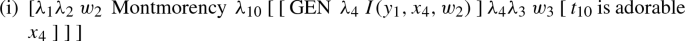

Examples like (54) show that the overt judge PP to Sue insulates the SP adorable from being interpreted with respect to the local judge, Mary. This, in turn, makes it possible for a bare use SP and an overt judge SP to share the same index, that introduced by the attitude, but end up interpreted with respect to different judges, hence the lack of contradiction in (54b). Note that in both cases Montmorency is judged as adorable for Sue only in Mary’s doxastic worlds. For all we know in the actual world, Sue could have never seen, and thus may have no opinion about, the dog.

We thus predict that overt judges are exempt from the judge-index correlation. Using our empirical diagnostics from Sect. 3.2, we show below that overt judge SPs do not require the de re reading of the DP containing them and are thus felicitous in de re blocking environments. In FID (55), the presence of an overt judge makes it possible to use contrary SPs without attributing contradictory beliefs to the attitude holder:Footnote 22

Likewise in the existential there and have constructions, an overt judge SP can be used to express a judgment that is contrary to that of the attitude holder, as in (56a) and (56b), respectively.

The data in (54)–(56) suggest that the distribution of overt judge SPs differs from bare uses, a fact also pointed out by Anand and Korotkova (2018) with respect to evidential requirements associated with certain SPs.Footnote 23 These data provide evidence against theories that treat covert and overt judges on a par (Stephenson 2007a, b; Stojanovic 2007; Pearson 2013a) and support theories with a special semantics for overt judges (Lasersohn 2005; MacFarlane 2014). That said, our goals in this paper are to concentrate on the way covert judges are fixed compositionally (including for SPs that do not take overt judge PPs, such as mediocre or smart) and to decide between theories of subjective meaning based on that. In the rest of the paper, we concentrate on bare uses of SPs.

3.4 Non-autocentric uses

Our discussion so far has been focusing on the so-called autocentric cases, ones where the covert judge of an SP is anchored to the speaker in matrix clauses. As shown in the previous section, many SPs allow overt judges and in those cases, the so-called exocentric perspective becomes possible. But an exocentric perspective is possible with covert judges as well, and Egan et al. (2005) and Stephenson (2007b) discuss examples where a non-human species under discussion facilitates this reading. (57) illustrates.

Likewise, we have assumed that the embedding attitude necessarily introduces a ‘reported autocentric’ perspective, and most of our examples are designed so that there are, in principle, two relevant perspectives, one of which is the attitude holder’s. However, as first noted in Lasersohn (2005: 678), embedded exocentric readings are also possible (58).

While it may be highly preferable to interpret a mainPred SP judge ‘autocentrically’ as co-referent with the attitude holder, the data in (58) demonstrate that this is not obligatory. As an anonymous reviewer notes, with this alteration, the term ‘local judge’ does not necessarily mean the attitude holder. It simply means the judge introduced by the local index, which is often the attitude holder, but may be some other salient perspective. However, reported exocentric readings become sharply degraded when a contrary SP is added, as in (59) below.

We suggest that introducing a contrary SP in (59) matters so much because it prevents exocentric readings like those in (58). As we discuss in Sect. 4.2, the data fall out naturally only in must associate theories, in which each index can only introduce one judge, either autocentric or exocentric. What is not allowed by the formalism, however, is having an autocentric and an exocentric judge simultaneously. Summing up, we see that even exocentric cases obey the judge-index correlation, even if the actual value of the judge is not the attitude holder of the embedding predicate. In the remainder of the paper, we will focus principally on reported autocentric readings in main predicate position, understanding that with a sufficiently rich context, another judge could be introduced by the attitude.

4 Consequences for theories of subjective meaning

The previous sections provide empirical evidence for the judge-index correlation. In this section, which comprises the theoretical heart of the paper, we use this correlation to adjudicate between existing theories of SP exceptionalism that postulate judges in the semantics of SPs. As we already discussed in Sect. 2.3, we categorize the existing theories into the following three classes depending on how judges and worlds are connected: (i) must associate theories, which obligatorily yoke judges and worlds together, (ii) can dissociate theories, which allow for a certain flexibility in how judge-world combinations are chosen, and (iii) must dissociate theories, which obligatorily disjoin judges and worlds.

We will argue that any theory in the first class will straightforwardly account for the data presented in the paper. The argument here is thus parallel to the one offered by Keshet (2008) for why worlds and times of evaluation need to be merged: they pattern together. We will show that while accounting for our data in theories from other classes is not impossible, it would require building in constraints that undermine the initial goal of unbundling the judge and the evaluation index. We want to emphasize again the following point. If there were no judges at all, SPs would be predicted to trivially follow Keshet’s constraints along with other ordinary predicates. However, as we discussed extensively in Sect. 2, most theories that deal with SPs postulate SP exceptionalism and among theories of SP exceptionalism most postulate judges in the semantics (with the exception of Anand 2009; Coppock 2018). Therefore, any theory with judges has to make sure that judges and worlds pattern together.

We start by presenting a basic extensional framework in Sect. 4.1, which we will further connect with an extensional theory of de re. Section 4.2 talks about must associate theories exemplified by an extensionalized version of Lasersohn (2005).Footnote 24 Section 4.3 talks about the overgeneration problem of can dissociate theories (Stephenson 2007a, b; Stojanovic 2007; Sæbø 2009). Section 4.4 discusses two must dissociate proposals, indexical contextualism along the lines of McCready (2007); Bylinina et al. (2014) (Sect. 4.4.2) and the logophoric binding approach in Pearson (2013a) (Sect. 4.4.3). We show that such theories crucially depend on a scopal view of de re—which in and of itself is problematic (Sect. 4.4.1)—to derive our cases as is, or require significant elaboration of the technology in question. Section 4.5 goes over a possible alternative implementation of the logophoric binding approach and shows that it does not solve the problem either.

4.1 Semantic assumptions

In Sect. 2.3, we introduced the basics of the extensional framework we are using in the paper. While an intensional systems treats indices as elements of evaluation sequence, we treat indices as present in the logical form and assume that all non-logical predicates require an argument of type I. Lexical entries for dog and brown in (60) illustrate.

The final I-type arguments of non-logical predicates will be filled by silent I-type bound variable pronominals present in logical form (indicated as \(i_n\) variables), and the the binders over these index variables are introduced by intensional operators such as attitude predicates as well as at the root node (Cresswell 1990; Percus 2000 and later work). The logical forms for the sentences Montmorency is brown and Mary thinks Montmorency is yellow are given below:

Expressions are evaluated relative to an assignment and a context, which we will assume for now is an element of the Cartesian type \(D_\kappa = D_e \times D_s\), corresponding to the author and world of the context. We assume the rules of Function Application, Predicate Modification, and Abstraction (Heim and Kratzer 1998):

With this set of assumptions, the semantics for (61a) is as follows:

Thus, the interpretation of a declarative sentence relative to a context and assignment is a proposition, and we define truth at a context (and assignment) as the evaluation of that proposition relative to the world of the context (64).

While we assume that the index argument of a non-logical predicate in main predicate position is supplied by a bound variable high in the clause, a nominal or adjectival predicate inside a DP requires some additional assumptions to fill its index argument. We will assume for explicitness here that determiners themselves compose with index variables, which they pass on to their complements (though nothing hinges on this implementational detail). (65) is the form for the indefinite determiner a:

We now consider the interpretation of the sentence A brown dog is a yellow fox, (66a). We assume the logical form in (66b) which involves movement of the subject DP a brown dog. (67) sketches the interpretative process, where \(g' = g[0/x]\).

The resulting truth conditions of the sentence in (66a) are, as desired, contradictory, a result of the fact that dog and fox are contraries (as, presumably, are brown and yellow). Importantly, when (66a) is embedded, as in (68), the sense of a contradiction vanishes:

Because think is an intensional operator, it introduces another intensional binder, per (69).

While this yields four potential logical forms combinatorically, we assume that the two expressed in (70a) and (70b) are ruled out by empirically motivated constraints that require clausal index variables to be bound by the closest binder (Farkas 1997; Percus 2000). Note that based on the rule for intersective modification applied in (67a), even in intensional environments we don’t have mixed interpretations such that brown and dog inside the DP a brown dog are interpreted with respect to different worlds.

This leaves only the last two forms, 70c and (70d). Assuming the interpretation of think is as in (69), the logical form in (70d) attributes to Mary a belief with the contradictory truth conditions in (67d).

In contrast, the form in (70c) yields a sensible interpretation, crucially because the witness for the existential is a brown dog not in \(i'\) but in the (bound) matrix world—that is, because it is interpreted de re:

4.2 must associate theories

The framework we introduced in the previous section sets the stage for a detailed discussion of SP exceptionalism in its various versions. As we have discussed in Sect. 2, the literature treats SPs as being semantically relativized to a perspective, or a judge. There are different ways to fix judges compositionally, and in this section, we take a closer look at must associate theories.

The basic tenet of such theories, first proposed in Lasersohn (2005) is the addition of a special judge coordinate, responsible for storing the evaluative perspective, to the index of evaluation (which we previously assumed consisted simply of a world of evaluation, hence of type \(D_s\)). Thus, indices are of Cartesian type \(D_I = D_e \times D_s\) where the entity coordinate of an index \(i=\langle j,w\rangle \) encodes \(\textsc {judge}(i)\), the judge of the index. (72) illustrates the semantic difference between ordinary vs. subjective predicates.

In this way, the truth conditions of some predicates are determined “relative to” an additional component of evaluation beyond worlds, and systems that involve something like a judge coordinate of the index are now known as relativist (see MacFarlane 2009, 2014 for discussion).

At the root level, the judge coordinate is conventionally set to a value supplied by the context, in parallel to the convention for worlds, as in (64). Thus, in this system contexts are of type \(D_\kappa = D_e \times D_s \times D_e\), corresponding to the author, world, and judge of the context. Lasersohn argues that in default cases SPs in a root declarative clause have what he calls an autocentric perspective: judge(c) is set to author(c), the speaker. As we already discussed in Sects. 3.3 and 3.4, in certain circumstances a third-party or a generic perspective is also possible. For now, we confine ourselves to autocentric and reported autocentric cases.

Following Stephenson (2007a), we will assume for now that attitudes quantify over indices such that the judge argument is co-referent with the attitude holder.Footnote 26 This means that what we observed for worlds of evaluation holds for judges as well. SPs that are interpreted de dicto in the scope of an attitude predicate are evaluated with respect to the attitude holder of that predicate, just as de dicto predicates in the scope of intensional operators are evaluated with respect to the worlds introduced by those operators (73).

In contrast, if the index argument for an SP is interpreted de re (i.e., bound by a non-local binder), then the world of evaluation will switch. Correspondingly, in multi-judge sentences like (74), this account predicts patterns of felicity to align with whether the nominal containing the attributive adjective is read de re. (74) illustrates. (While in our scenario there is a specific dog, note that de re indefinites don’t have to be specific, see Fn. 19 and Sect. 4.4.1. We assume that the difference is not a matter of scopal distinctions.)

In (74), an adorable dog is read de re and evaluated with respect to \(i_0\), therefore, adorable also is evaluated with respect to \(i_0\) and the matrix judge (by assumption, the speaker). If an adorable dog were read de dicto, the SPs adorable and ugly would be evaluated at the same index, the embedded \(i_1\). This would mean that they would be evaluated with respect to the same world and the same judge (by assumption, Mary), yielding a contradiction.

In order for (74) to be non-contradictory, adorable and ugly have to be evaluated with respect to either (i) different worlds: the same object can be adorable for the speaker in the actual world and ugly for the speaker in someone’s doxastic alternatives, or (ii) different judges: the same object can be adorable for the speaker and ugly for Mary in the same world. An important empirical prediction of Lasersohn’s theory is that judges and worlds pattern together, since they are both part of the index. One cannot evaluate adorable with the speaker as the judge in (74) without evaluating it in the matrix world, which prevents mixed non-attested readings which we have seen in (40) and to which we come back in the next section. This is the judge-index correlation, and it follows naturally from the architecture of Lasersohn’s system.

Note that this type of framework also easily handles exocentric uses discussed in Sect. 3.4. For example, in line with Lasersohn (2005), we may model this by adding an argument to the denotation of attitude predicates for the embedded judge (75).

For the lexical entry in (75) we assume the judge element is a free variable implicit argument of the attitude, and hence may (a) be bound by the subject, to derive a report of an autocentric judgment, or (b) be free, to produce exocentric readings without requiring a non-local world of evaluation. Crucially, each index introduces only one judge, and all SPs relative to an index will be relativized to the judge of that index. This ensures that even exocentric readings obey the judge-index correlation.

The above logic makes use of the mechanisms of de re interpretation, and hence could be dependent on the details of a particular account. Within the extensional theory we have been developing, de re interpretation is done by non-local binding of an index variable. Another (more traditional) approach pursued within intensional approaches is the Scope Theory (Russell 1905; Montague 1973; Cresswell and von Stechow 1982). In such an approach, de re interpretation involves a logical form in which the de re nominal has moved from its base position to one above the attitude predicate, as in (76) below:

As the nominal is outside the scope of the intensional operator, its index variable cannot be bound by the intensional operator, and hence must be bound by the matrix binder. The Scope Theory thus allows us to derive the non-local interpretive effects of de re without requiring non-local binding (it is for this reason that the Scope Theory is used by many intensional systems, since many cannot capture something like non-local binding otherwise). As we shall observe, some theories of judge-dependence disallow non-local judges (particularly, the approaches in Stojanovic 2007 and Pearson 2013a), and so such theories will require some version of the Scope Theory if non-local judges are available.

Relativist frameworks in Egan (2010), MacFarlane (2014) and Bylinina (2017) work very similarly to Lasersohn (2005) with respect to our data. In these approaches, evaluation indices reserve a coordinate for the judge, which various perspectival expressions are sensitive to. Because of this bundling, such theories will straightforwardly derive the correlation we have observed, parallel to how they would derive Keshet’s (2008) original time-world correlation.Footnote 27 In the next sections, we will argue that all extant contextualist approaches fail to do the same. Our data thus provide a novel argument for a relativist semantics for subjective meaning.

4.3 can dissociate theories

A spate of more recent theories have reacted to the original relativist position by dissociating judges and evaluation indices. Here, we will consider theories that fall under the umbrella of what we will call implicit variable approaches: the mixed contextualist/relativist framework of Stephenson (2007a) and the mixed contextualist/variable-free framework of Sæbø (2009), which builds off the contextualist theory of Stojanovic (2007).

Despite different conceptual underpinnings, those accounts share the following formal property. They provide two routes for the specification of an SP judge, treated as a pronominal element with a bound interpretation and or a free interpretation. In case of the former, the judge is linked to the evaluation index, much like in Lasersohn (2005). However, in the latter, “free”, case, the bare use judge can pick up any referent. We will show momentarily that the “free” route predicts the existence of de dicto non-local judge interpretations that are systematically absent for multi-judge cases. We will thus claim that the implicit variable theories of SPs are too weak in their current form and predict unattested readings. We start by discussing the account in Stephenson (2007a) and then show that the proposal in Sæbø (2009) is the same as far as our data are concerned.

Stephenson (2007a) assumes alongside Lasersohn (2005) that indices contain a judge coordinate, which attitude verbs shift as in (69) in Sect. 4.1. In addition to that, all SPs are treated as dyadic predicates:

Two kinds of implicit variables can fill the z judge role.Footnote 28 In autocentric cases, the judge argument is filled by the distinguished pronominal PRO\(_J\) that picks out the judge coordinate of the index of evaluation. The result in (78c) is identical to Lasersohn’s (2005), given in (63).Footnote 29

However, in addition to autocentric uses, SPs also allow non-autocentric readings, as we discussed in Sect. 3.4. How such cases are handled constitutes one of the crucial differences between the approach in Lasersohn (2005) and the one in Stephenson (2007a). For Lasersohn, non-autocentricity arises purely due to pragmatics. Because SPs are semantically judge-dependent in the same way across the board, the judge, autocentric or not, is always linked to the index of evaluation, which is all that matters for our cases. For Stephenson, however, there is a semantic difference between autocentric and non-autocentric uses. In this system, non-autocentric readings arise when the z role is filled by a free variable, \(pro_i\):

Importantly for our purposes, the account in (79) overgenerates in attitude reports.Footnote 30 Due to the lack of restrictions on the distribution of \(pro_i\), nothing prevents a speaker-oriented SP from combining with a de dicto nominal in the subject position in the complement clause. However, as shown in (80) (=39), such reading is not attested (cf. also 33 in Sect. 2.3). A derivation for the non-attested mixed reading (80b), which is not ruled out by Stephenson (2007a), is given in (81):