Abstract

Mainstream political liberals hold that state coercion is legitimate only if it is justified on the grounds of reasons that all may reasonably be expected to accept. Critics argue that this public justification principle (PJP) is self-defeating, because it depends on moral justifications that not all may reasonably be expected to accept. To rebut the self-defeat objection, I elaborate on the following disjunction: one either agrees or disagrees that it is wrong to impose one’s morality on others by the coercive power of the state. Those who disagree reject PJP, they understand politics as war. Those who agree accept PJP, they understand politics as competition. Political competitors abide by PJP to avoid politics as war, by enforcing PJP on political combatants they engage in a war that is unavoidable. In both cases their exercise of political power has a justification that is reasonably acceptable to all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mainstream political liberals hold that state coercion is legitimate only if it is justified on the grounds of reasons that all may reasonably be expected to accept.Footnote 1 Some of their critics argue that this consensus-oriented public justification principle (PJP) does not meet the reflexivity requirement (RR), meaning that the principle does not satisfy its own criterion of legitimacy.Footnote 2 Apparently, the public can be so profoundly divided that not all of its members may reasonably be expected to accept PJP. For instance, while atheists can hardly be reasonably expected to accept religious reasons, it is, perhaps, even less reasonable to expect that religious citizens restrain themselves from using such reasons in the public justification of their preferred legal provisions. In a word, PJP seems to be self-defeating. I will defend the consensus-oriented PJP from the self-defeat objection.

To begin with, I will distinguish between two specific ways of formulating this objection. The first is to argue that some citizens may reasonably reject political liberals’ justificatory reasons for PJP. The second is to argue that some citizens may not be reasonably expected to accept these reasons. As I will explain, only the second formulation poses a genuine challenge to PJP (Section II).

Then I will review the existing attempts to rebut the self-defeat objection. Some deny that RR is applicable to PJP,Footnote 3 or argue that, if formulated properly, RR poses a problem in theory but not in practice.Footnote 4 Others defend PJP by claiming that only improperly qualified (unreasonable) members of the public reject it.Footnote 5 I will argue that these attempts have only been partially successful (Section III).

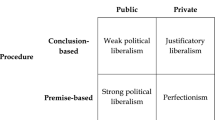

In my response to the self-defeat objection I will not try to expose its alleged inconsistencies. Instead, I will simply argue that PJP meets RR — there is a justificatory reason in favor of PJP that all may reasonably be expected to accept. This reason is grounded in a political choice that is crucial for a self-standing conception of political liberalism. The choice stems from two distinctions.

The first distinction is between morality and law. I will argue that there may be a ‘discontinuity’ between them: a moral rule and a legal provision may be inconsistent with one another, and at the same time both may be recognized as normatively valid by one and the same person. This makes it possible to defend PJP as a legal-political principle on nonmoral grounds (Section IV).

The second distinction is between two ways of understanding politics—either as competition or as war. The ‘party of competition’ recognizes the discontinuity between morality and law. Political competitors do not think that it is right to use the coercive power of the state in order to impose one’s moral vision on others through laws and judicial rulings. Accordingly, they accept PJP. The ‘party of war’ denies or seeks to eliminate the discontinuity between morality and law. Political combatants think that politics is about defending and promoting one’s moral vision by laws and judicial rulings backed by the coercive state power. Accordingly, they reject PJP (Section V).Footnote 6

As I will demonstrate, PJP meets its own criterion of legitimacy: those who abide by PJP exercise political power in a way that has a justification that all — even those who eventually reject PJP — may reasonably be expected to accept (Section VI). The argument is summarized in the Conclusion.

Formulating the self-defeat objection

The self-defeat objection against PJP has the following general form:

-

(1)

PJP: Legal provisions backed by the coercive power of the state are legitimate only if they are justified on the grounds of reasons that all may reasonably be expected to accept.

-

(2)

The fact of reasonable pluralism: Under the conditions of deep disagreement, PJP is not justified on the grounds of reasons that all may reasonably be expected to accept.

-

(3)

RR: PJP must be justified on the grounds of reasons that all may reasonably be expected to accept.

-

(C)

Conclusion: PJP is illegitimate.

The concrete content within this form varies mainly in how one explains why the premise (2) is true. Two explanations are usually offered.

Some may reasonably reject the rationale for PJP

According to Joseph Raz, the extent of pluralism in contemporary liberal societies makes it “safe to assume” that no argument in the process of public deliberation can be acceptable to all.Footnote 7 PJP does not seem to be an exception. It is disputed even among liberals themselves, not to speak of conservative or fundamentalist members of the public. One cannot reasonably expect all people to accept the reasons that, in political liberals’ view, justify PJP.

Political liberals counter this intuition by arguing that PJP is not meant to be justifiable to literally ‘all’ without any qualifications. On the standard interpretation of PJP, ‘all’ is a shortcut for ‘all reasonable citizens’,Footnote 8 i.e. those citizens who are willing to abide by fair terms of cooperation and recognize the burdens of judgment.Footnote 9 By appealing to reasonable expectations about the acceptance of reasons PJP predetermines a certain qualified group to which public justification is addressed. As David Estlund has argued,Footnote 10 the fact that PJP’s legitimacy depends on the acceptance by a qualified group, whose boundaries are predetermined by PJP, is a logical consequence of its self-application. Given this preselection, it is never safe to assume that those who might reject PJP are at the same time those who are qualified to do it. Only the acceptance by reasonable citizens is necessary for PJP to meet its own criterion of legitimacy.

Accordingly, some advocates of PJP argue that all reasonable people necessarily accept it, because reasonable people accept those liberal political values on which the principle is based. For Jonathan Quong, to be reasonable is to accept liberal values of freedom, equality, and fairness, which, in his view, entails the acceptance of PJP.Footnote 11 Andrew Lister associates reasonableness with the pursuit of civic friendship across deep disagreement, he considers this friendship impossible without accepting PJP.Footnote 12 Their opponents argue that it is not necessary for reasonable people to accept PJP. As Franz Mang puts it, “philosophical critics of public reason, such as Raz and Wall, generally endorse liberal values including liberal tolerance and mutual respect. They are not unreasonable people who deny liberal values; their understanding of these values is in many ways different from public reason philosophers’ and therefore, they reject public reason.”Footnote 13

Mang’s argument reveals the limitations of attempts to declare PJP’s self-defeat on the grounds that some liberal philosophers reject it. The fact that PJP is not the only plausible interpretation of liberal political values does not make it unreasonable to think that the supporting rationale for PJP is acceptable to all liberals. On the contrary, if liberal opponents of PJP, such as Mang, agree that this principle represents one possible way to realize liberal political values — the values that they themselves accept — it is not clear why they may not be reasonably expected to accept the rationale for PJP that political liberals provide.Footnote 14

Furthermore, Mang argues that “[liberal] philosophers who reject public reason generally do not claim that people should be allowed to freely impose their comprehensive doctrines on one another.”Footnote 15 If this is true, then there seems to be a very fine line of separation between political liberals and their liberal opponents. So, it becomes even less clear why the acceptance of the rationale for PJP by all liberals should be beyond reasonable expectation. I would say that in this case the defense of the premise (2) in the self-defeat objection is too vague to make it a strong argument against PJP.

Some may not be reasonably expected to accept the rationale for PJP

Another explanation of why the premise (2) in the self-defeat objection is true targets the key justification for PJP that is routinely invoked by mainstream political liberals. In their view, PJP is entailed by the duty of equal respect for all fellow citizens as partners in democratic deliberation.Footnote 16 It is overtly dogmatic and patronizing to expect that individuals will accept justificatory reasons derived directly from those religious and philosophical doctrines of the good that they deeply disagree with. Therefore, under the conditions of deep moral disagreement, respect for others as free and equal citizens requires that we do not support the exercise of the coercive power of the state that is justified solely on the grounds of some comprehensive moral doctrine. As James W. Boettcher has put it: “…To demand that other citizens adopt the standpoint of a comprehensive doctrine in order to avail themselves of the justifying reasons for answers to fundamental political questions is to disregard their status as free citizens. It is to disregard their moral power freely to endorse a rival doctrine and conception of the good.”Footnote 17

The problem with justifying PJP on the grounds of equal respect is that the latter is not a universally accepted moral value.Footnote 18 At least, not everyone gives it the same priority as it enjoys among liberals, and not everyone thinks that the requirement of equal respect entails the acceptance of PJP.Footnote 19 Religious people may think that the pious deserve more respect than the blasphemous. Communitarians and conservatives may think that respect for individuals should be balanced with respect for the traditional values and interests of communities. Finally, there can be conflicting interpretations of what respect for one’s opponents in public deliberation means. One can argue that precisely by restraining ourselves from addressing fellow citizens with reasons that do not fit into their comprehensive doctrines we show lack of respect for them as rational and reasonable persons capable of deep critical and self-critical engagement with the views of others. It is possible to invert Boettcher’s argument ironically and say that to avoid appealing to one’s comprehensive doctrine is to disregard others’ moral power freely to endorse a rival, not just their own current comprehensive doctrine.

To summarize, I think the strongest formulation of the self-defeat objection is the following. PJP excludes justifications derived directly from comprehensive moral doctrines. At the same time its own justification draws heavily on the requirement of respect for fellow citizens as free and equal persons, which is central to a particular interpretation of a particular — distinctively Kantian — comprehensive moral doctrine. Not everyone may reasonably be expected to accept this doctrine or its particular interpretation. Therefore, PJP does not meet RR, it is self-defeating. Holding on to PJP makes political liberals guilty of “moral authoritarianism.”Footnote 20

How to respond to the self-defeat objection?

In this section I will review several prominent responses to the self-defeat objection, explain where I think they succeed and fail, and outline the strategy for my own response.

Rejecting the reflexivity requirement

Some try to dismiss the self-defeat objection at the outset by denying that PJP applies to itself. One way of demonstrating that PJP does not have to meet RR is the following.Footnote 21 PJP defines a criterion of legitimacy for legal provisions. Whether or not it is a good definition depends on whether or not it meets the criteria of a good legal and political theory. Obviously, the criteria of a good legal and political theory may well be different from the criteria of legitimacy of legal provisions.Footnote 22 Therefore, PJP does not necessarily apply to itself. It would apply to itself only if it were a legal provision.

Drawing on a similar logic, Sameer Bajaj argues that PJP is a “fundamental principle of political morality,” which sets a certain moral standard for “political rules the state imposes,” but it is not itself a “political rule,” therefore, it does not apply to itself.Footnote 23 In other words, PJP determines which laws are legitimate, but, since it is not itself a law, it aspires only to be morally right and not legitimate in the same sense as a law might be.

I agree that Bajaj’s solution saves PJP from the self-defeat objection. But, I am afraid, it is a Pyrrhic victory won at the cost of depriving PJP of the lion’s share of its potential significance for politics. If, under the threat of immediate self-defeat, PJP cannot even aspire to become a law, then political liberals have to recognize that it must always remain legal to ignore it. Bajaj attempts to mitigate this concern by arguing that the adherents of PJP do not have to passively tolerate its violation. They “can respond by getting into the trenches of democratic politics to bring about a publicly justified political order.”Footnote 24 But, in my view, this response does not quite address the pragmatics of debates about the principles of legitimacy.

The whole point of grounding legislation in principles is to establish certain norms as basic legal foundations that cannot be easily altered at the turn of every election cycle. For example, the idea of religious non-establishment was elevated to the level of a legislative principle and inscribed into the constitutions of several democratic states precisely to ensure that citizens do not have to get into the trenches — both metaphorical and real — each time some part of the legislature experiences a fit of religious enthusiasm. Thus, strictly speaking, Bajaj’s solution saves PJP from self-defeat in theory, but it rather contributes to its self-defeat in practice, for the critics of public reason are only happy to hear that PJP must never become law.

Reformulating the reflexivity requirement

Kevin Vallier acknowledges that the consensus-oriented PJP applies to itself, but he contends that “the arguments for self-defeat rely on an implausibly strong version of RR.”Footnote 25 As he explains, PJP would really fail to perform its reconciling function only if its rejection by some reasonable citizens meant that we have to give up certain critically important laws, such as laws protecting basic rights. But if, instead, the rejection of PJP prevented us only from reconciling over some minor laws (e.g. a set of marketing regulations), “then we would do better to simply reject such laws than to give up public justification requirements.”Footnote 26 Hence the following reformulation of the self-defeat objection with a weakened RR:

-

“(1*)

State coercion is morally permissible only if it is publicly justified (public justification requirement).

-

(2*)

Some reasonable people reject a public justification requirement in cases when it is necessary for publicly justifying a critically important law L.

-

(3*)

A public justification requirement cannot be a genuine moral requirement if it is defeated by or publicly unjustified for some reasonable people when it is necessary for publicly justifying a critically important law L.

-

(C*)

The public justification requirement is not a genuine moral requirement [(2*), (3*)].”Footnote 27

Having reformulated the self-defeat objection this way, Vallier then argues that the premise (2*) is false. That is because it is highly unlikely that some critically important law could not be justified to reasonable people, unless they accepted PJP. On the contrary, “in many cases, our commitments to various policies are many,” and most people do not even know anything about PJP.Footnote 28

Thus, in Vallier’s view, the self-defeat objection fails, if we reformulate RR in a “more plausible” way. Having done this, we see that “cases of self-defeat will be rare, as members of justificatory public will seldom employ public justification requirements as reasons,”Footnote 29 and even when they do, the disagreement over such requirements does not undermine critically important liberal laws, for there are multiple other grounds on which these laws can be justified to reasonable people.

I think Vallier’s defense of the consensus-oriented PJP involves two big concessions that political liberals can hardly afford. Firstly, by agreeing to deal only with a significantly weakened version of RR Vallier concedes implicitly that, in principle, PJP is self-defeating. His contention that RR is “implausibly strong” may well be understood in the sense that intuitively PJP is unlikely to meet RR even in a public that consists of reasonable people. Secondly, by emphasizing that PJP hardly ever figures in the actual justifications of critically important liberal laws — which, nevertheless, happen to meet PJP — Vallier concedes that, in fact, invoking PJP is not necessary for justifying these laws to reasonable people. Even if reasonable people disagree about PJP, by accepting critically important liberal laws they still act like they do not disagree about it. It turns out that the possibility of disagreement about PJP should not concern us too much, because it is not even necessary to mention PJP in order to justify critically important liberal laws to reasonable people. Thus, Vallier concedes that PJP is self-defeating as a matter of principle, and PJP is not particularly important as a matter of practice.

In my view, a stronger defense of PJP is desirable. Also, I do not think that, if PJP does not figure in political debates outside the academic literature on political liberalism, it is not necessary or unimportant for justifying critically important liberal laws. PJP does not have to be understood simply as one justificatory reason for liberal laws among many other reasons, such as those that draw on the ideas of tolerance, equal liberty, reciprocity, fairness etc. Instead, PJP may well be understood as a general rule for realizing these ideas in the legislative and judicial practice of liberal democracies. On this interpretation, PJP is not just another requirement addressed to liberal democratic citizens alongside the requirements to be tolerant, respectful, and fair. But PJP is a summary and explication of what it means to be tolerant, respectful, and fair to one’s fellow citizens as citizens — namely, to support only those legal provisions that are justified on the grounds of reasons that all may reasonably be expected to accept.

Limiting the justificatory constituency

A yet another way of dealing with RR is to argue, following Estlund, that the reasons specified by PJP must be acceptable only to properly qualified members of the public, and only those who accept PJP are properly qualified.Footnote 30 Here the main task is to identify the qualified group in a way that would be neither vague, nor self-serving. So, on the one hand, as I have argued in section II.A, it would be too vague to define the properly qualified merely as ‘reasonable citizens’. But on the other hand it would also be a bad solution to say that PJP must be acceptable only to those whose favorite book is John Rawls’s Political Liberalism.

Apparently, Andrew Lister offers a version of the qualified acceptability argument that successfully avoids being vague and self-serving.Footnote 31 He limits the justificatory constituency to those members of the public who embrace the ideal of civic friendship. In Lister’s view, PJP is necessary for maintaining the relations of reciprocity, or civic friendship, under the conditions of deep moral disagreement among citizens when “pluralism makes richer forms of community unattainable.”Footnote 32 Those who reject PJP acknowledge thereby that they are not interested in civic friendship across deep disagreement. They do not see much importance in establishing the relationships of reciprocity with other members of the public, so they do not have the necessary motivation for considering the question of whether or not justificatory reasons are publicly acceptable. These unfriendly citizens are not properly qualified to pass the judgment about the justification of PJP. Therefore, in Lister’s view, once I accept PJP, no objection against it deserves my attention, because “I have no reason to care about the acceptability of a reason to people who do not care about qualified acceptability.”Footnote 33

I think Lister’s defense of PJP involves a non sequitur. Namely, if some citizens do not care about reciprocity, it does not follow that political liberals have no reasons to care about justifying PJP to them. Insofar as I accept PJP, I care about legal provisions and principles being justified to my fellow citizens. If I take reciprocity to be the best justification for PJP, I just need to make my opponents care about reciprocity, and then I may reasonably expect them to accept PJP. Furthermore, even if I fail to make my opponents care about reciprocity, it does not mean that I have lost all reasons to care about justifying PJP to them. I still accept PJP, which means that I still care about legal provisions and principles being justified to my fellow citizens. So, I might try to justify PJP on the grounds of some other values that we all may reasonably be expected to accept.

To generalize, if I accept PJP for whatever reason, I care about legal provisions and principles being justified to all citizens. This includes caring about PJP being justified to all citizens, which is an implication of PJP’s self-applicability that has nothing to do with the exact reasons why I accept PJP and others do not.

The upshot is that there is hardly a non-self-serving way to limit the justificatory constituency of PJP in order to defend it from the self-defeat objection. Justifying PJP to people is the way to make them care about legal provisions and principles being publicly justified. What other more important tasks do public reason liberals have, if it is not to make people care about public justification? So, even if there are people who really do not care about the acceptability of reasons for state coercion to all citizens, they are not to be excluded from the justificatory constituency of PJP. On the contrary, it is these people to whom the theory of public reason should be addressed in the first place, because those who already accept public reason — perhaps, on some intuitive grounds — are the last ones to ask for a well-developed theory of it.

Relying on public reason’s own strengths

In my defense of PJP I will not try to avoid RR, nor will I gerrymander the justificatory constituency of public reason. Instead, I will argue that PJP unequivocally meets RR, i.e. the premise (2) in the self-defeat objection is false. My argument will rely on the following two strengths of PJP.

First, PJP has a relatively narrow scope — it applies to the exercise of the coercive state power. It means that PJP is a modest legal-political principle, not an ambitious statement about the foundations of all morality. Therefore, within its proper limited domain PJP may be presented as a reasonable requirement even to those who tend to consider it flawed in a wider moral context.

Second, PJP is not a particularly demanding principle. It does not require that justificatory reasons be actually accepted by all, nor does it require that justificatory reasons be of the kind that all must accept. PJP requires only that justificatory reasons be such that all may reasonably be expected to accept them. So, the principle does not require that citizens support their preferred legal provisions by arguments that already have universal acceptance or by arguments that are fully normatively warranted to mandate it. PJP only requires that citizens’ expectations regarding the universal acceptance of their arguments be reasonable.

According to Rawls’s definition of reasonableness,Footnote 34 a reason-giver’s expectations about her arguments being accepted by all are reasonable if she recognizes the burdens of judgment and offers fair terms of cooperation to all, including those who tend to oppose her. The burdens of judgment clause means that the reason-giver must not claim to be arguing on behalf of the whole truth.Footnote 35 The fairness clause means that the reason-giver must demand from others neither more nor less than she would demand from herself, if she were in the place of those others.Footnote 36

Thus, attempting to present PJP as an inevitable conclusion from some moral truth or value that all must or would willingly embrace is not necessary, nor is it helpful under the conditions of deep moral disagreement. The conditions of deep moral disagreement are by definition the conditions under which there is no such ranking of moral values that all cannot but accept. Instead, in order to justify PJP within its sphere of applicability and according to its own justificatory standard, it would be sufficient to present it as a political option supported by reasons that do not affirm any controversial religious, philosophical, or moral doctrines, and explain why choosing this option is necessary for maintaining fair terms of cooperation.

The political choice that I think is crucial for justifying PJP is determined by two foundational distinctions: one is between morality and politics, and the other is between politics understood either as war or as competition. I draw these two distinctions in Sections IV and V respectively. In Section VI I demonstrate how PJP resolves the controversy around these distinctions in a way that allows it to meet RR.

Political not moral

The discontinuity between morality and law

Distinguishing between moral principles on the one hand and legal-political principles on the other is important insofar as there may be a discontinuity between morality and law. A moral rule and a legal provision may require that a person act in two different ways that are strictly opposite to one another, but at the same time the person in question may agree that both the moral rule and the legal provision are valid, or correct.

The paradigmatic case for such discontinuity is retaliation. Let us take the least eccentric example. Many ordinary, not particularly sociopathic people consider punching an impudent offender morally right, but at the same time they agree that brawling must be legally prohibited. So, a law that prohibits individuals from engaging into fights with one another mandates that they do not do what in some cases they consider morally right and requires that other individuals (police officers, judges, marshals etc.) punish them if they violate the prohibition. Applying the legal sanction in this case means punishing people for doing what is morally right, which makes this application morally wrong.

Another case for the discontinuity between morality and law is the fact that sometimes the moral gravity of certain acts does not parallel their gravity from the perspective of the law. For example, in contemporary Western societies robbery is a crime and cheating on one’s spouse is not. Meanwhile, our cultural and moral conscience allows for a figure of a ‘noble highwayman’ and not for that of a ‘noble cheater’. Thus, from our moral point of view, cheating is sometimes worse than robbery, despite the fact that only the latter and not the former is subject to criminal prosecution.

These examples show that the hierarchy of moral transgressions does not translate itself neatly into the hierarchy of legal offences. The inconsistency between morality and law may be so profound that one and the same act may be simultaneously morally praised and legally punished. I call this ‘discontinuity’, not ‘contradiction’, because ‘contradiction’ would suggest that any inconsistency between morality and law represents some kind of dysfunction, as if they were meant to serve the same purpose or a coherent set of purposes, which is not necessarily the case.

In the first example, impudent offenders are considered punchable because of the moral duty to protect oneself and others from deliberate humiliation. In the second example, ‘noble highwaymen’ are morally praised for actively, although, perhaps, too impatiently, seeking to remedy the injustices of the world around them. However, allowing everyone to punch and expropriate others whenever one feels morally entitled to do so is a recipe for chaos. In contrast, when it comes to cheating on one’s spouse, we struggle to find anything morally praiseworthy in such behavior. Yet, this behavior is not criminalized by law, because legal penalties would hardly help anyone keep a loving relationship with another person, which is the point of faithfulness in the first place.

It seems, the purposes of moral rules on the one hand and legal provisions on the other may be different and not necessarily coordinated. In other words, it is possible to draw a functional distinction between them. Let us say that moral rules determine the course of action that corresponds to whatever motive or purpose a particular moral doctrine claims to be fundamental, e.g. to be happy, live up to one’s dignity as an autonomous subject, fulfil one’s duties before God etc. Meanwhile, legal provisions determine which course of action is to be backed by the coercive power of the state in order to maintain peace among citizens. Here and in what follows I use ‘peace’ as a shortcut for what Bernard Williams described as the subject of “the first political question” — namely, “order, protection, safety, trust, and the conditions of cooperation.”Footnote 37

One way to question this distinction is to contend that legal provisions may be aimed at a variety of purposes, and for many of these provisions maintaining ‘peace’ — even in the wide sense of the word — is only a derivative goal. For example, tax laws may be said to deliver peace, but only because they deliver justice.

My response is that no matter how distant the purpose of maintaining peace may be from a particular area of legislation, this purpose defines the primary necessary condition for the legitimacy of any legal provision. Whatever laws are aimed at, they cannot pursue their aims at the cost of causing disruption. For example, people may have very radical views on which system of taxes and benefits is just, but the system cannot be organized in a way that makes one part of the citizenry feel as if it is being subject to extortion for the benefit of the other. Otherwise, taxpayers cannot be reasonably expected to cooperate with tax authorities, which means nothing else but failure to maintain legal order in the field of taxation.

Legislators may be more or less idealistic or pragmatic, revolutionary or conservative, but there are hardly any legislators that would not consider how their decisions are going to affect public order, safety, and stability. If certain activities and relations between individuals are not expected to become more well-ordered due to the control and sanctions on the part of the state, then there is no point in legislating on them. State laws may be directed at various immediate aims, but they cannot be not aimed at maintaining peace. In contrast, this is not necessarily the case with moral rules and principles, for there may well be such thing as a moral duty of retaliation demanding that one’s thoughts “be bloody, or be nothing worth.”Footnote 38

Another way to question the functional distinction between morality and law is to argue that the difference between the norms that can and cannot be rightfully enforced may itself be moral in nature.Footnote 39 In particular, the pursuit of peace may be understood as a moral obligation.Footnote 40 Therefore, the objection might go, it is not necessary to leave the realm of morality in order to distinguish between enforceable and non-enforceable norms, as well as between rules that are aimed at peace and rules that are aimed at other societal values, such as justice, liberty etc.

In reply, I am ready to concede that the tension between the pursuit of peace and the pursuit of other societal values can be described in terms of discontinuity within morality itself. But ultimately, whether we should speak of discontinuity between morality and law or discontinuity within morality is a verbal dispute. I prefer speaking of tensions between morality and law, or between the moral and the political. This is a more operable language, as it allows to avoid needless moral paradoxes, such as the paradox of a morally justified moral compromise.Footnote 41

Public justification in a nonmoral sense

The discontinuity between morality and law means that public justification of legal provisions is not necessarily the same as their moral justification. Public reason is not necessarily a moral reason. In many cases moral justifications for legal provisions are deemed sufficient by the general public, but it does not have to be so. If the discontinuity between morality and law exists, legal provisions may be justified on their own nonmoral grounds, and sometimes, as the examples of brawling and robbery suggest, such justification may be crucial. The same holds for legal-political principles — they do not have to be understood only as rules of ‘political morality’. Legal-political principles may be turned into actual laws, say, by making them part of a country’s constitution. Constitutional provisions may be justified on moral grounds, but sometimes, under the conditions of deep moral disagreement, these are not the best justifications and not the ones that meet PJP. If public justification of constitutional principles across deep moral disagreement is at all possible, it most likely involves nonmoral reasoning.

For example, the principle of religious non-establishment has a well-known moral justification on the grounds of equal respect for everyone’s conscience understood as “a precious internal faculty… for searching for life’s ethical basis.”Footnote 42 This justification may sound inspiring to liberals, but unfortunately it is far from being persuasive to devout believers. They would say that the God-given “precious internal faculty” to choose one’s own path in life is misused when a person turns away from the guiding light of the divine truth. For some religious people, to refrain from keeping one’s neighbors on the right path by all means possible, including the state support of the true church, is to put human liberty above God’s commandments. Bearing this in mind, the head of Russian Orthodox Church Patriarch Kirill did not mince his words when in 2016 he publicly condemned the idea to “put the rights of man above God’s word” as a “global heresy of manworshipping.”Footnote 43 If religious non-establishment has any chance to win the acceptance of such individuals as Patriarch Kirill, it is more likely to do so as a means of establishing social peace, a way to avoid alienating religious minorities from the state and the majority of citizens. Furthermore, it is this conciliatory justification of religious non-establishment that turns out to be really compatible with PJP, not the moralistic justification on the grounds of equal respect for conscience. As we have just seen, the latter may well be interpreted by religious citizens as an integral part of the doctrine of secular humanism, which they may not be reasonably expected to accept.

By analogy, PJP may be turned into a constitutional principle similar to the principle of religious non-establishment but extended to all comprehensive doctrines, secular and religious. It will block as unconstitutional any legal provision that is supported solely by reference to some religious, philosophical, or other ideological dogma, be it Catholicism or atheism, Kantianism or utilitarianism, socialism or libertarianism. Alongside the justifications that draw on the moral value of equal respect for conscience, PJP can be justified pragmatically as a necessary condition for social peace, trust, and cooperation under the conditions of deep moral and ideological disagreement among citizens. This conciliatory justification does not even remotely contest the religious view of non-believers as ‘damned’, nor does it question the merits of any other moral doctrine, secular or religious. It is the kind of justification that I would call political, not moral.

An important note is necessary before we move forward. The conception of discontinuity between morality and law obviously alludes to legal positivism.Footnote 44 But here I do not imply that legal positivism is true (nor am I going to claim that it is false). This is because I do not wish my justification of PJP to be dependent on accepting the truth of a widely contested philosophical doctrine of law, for in this case it will be easily dismissed as the one that not all may reasonably be expected to accept.

Similarly, my discussion of public justification in a nonmoral sense has a lot to do with the political realist statement that “political philosophy should not seek to regiment politics through morality,”Footnote 45 but I do not mean to defend or defeat it. I do not wish to ground the justification of PJP in accepting the truth of political realism for the same reason that I remain skeptical about legal positivism.

Finally, I do not even argue that the conception of discontinuity is the true representation of how morality and law are related, nor do I claim that it is the right way to think of what this relation should be. By claiming that there may be a discontinuity between morality and law I only point towards an apparent tension between the two and offer its possible interpretation. Whether one accepts or rejects this interpretation defines the two ways of understanding politics that I discuss in the next section.

Competition not combat

Politics as war

Some may remain unconvinced that being a means of social peace makes PJP acceptable as a political principle, let alone a constitutional essential. They may disagree that peace is the central aim of politics and claim that the realization of their particular view of the good is much more important. This conviction may go along with the idea that genuine social reconciliation is possible only on the basis of a concept of the good that is shared by all citizens. In other words, some may think that their preferred conception of the good must not be downplayed and compromised for the sake of peace. They reject the idea of discontinuity between morality and law and think that it is their moral duty to eliminate the inconsistency between the two wherever it emerges. As a consequence, such people reject PJP, they do not think that it is illegitimate to impose their moral values on others by the coercive power of the state.

‘We are going to impose our values on you by the coercive power of our state regardless of whether or not you may reasonably be expected to accept them’ sounds much like a declaration of war. Therefore, I think it would be correct to remind ourselves of the famous Michel Foucault’s definition and say that those who reject PJP understand politics as “the continuation of war by other means”Footnote 46 — in the case of modern democracies not by means of fighting in the battlefield but by arguing over legal provisions at parliament and in court. This is not to say that such political combatants, or the ‘party of war’, as we may call them, endorse war for its own sake and relish all sorts of battles. But still, in their view, war is the essence of politics. They understand politics as a struggle for domination between irreconcilable factions that seek to get hold of the state power in order to impose their preferred values on others through laws and judicial rulings.

When in the majority, political combatants impose their moral vision on the whole society through laws justified on the grounds of their preferred ideological dogmas. When in the minority, they still seek to do the same, although in this case they resort to demands for legal accommodation within the larger society through special group-differentiated rights and exemptions from generally applicable laws, regardless of whether or not the laws in question are publicly justified. The imposition of sectarian religious or cultural dogmas on others takes place in both cases. In the case of a publicly unjustified law the coercive power of the state is used to force citizens to engage in or refrain from a certain practice on the grounds of reasons that they may not be reasonably expected to accept. In the case of a publicly unjustified exemption the coercive power of the state is used to force citizens to tolerate a certain practice on the grounds of reasons that they may not be reasonably expected to accept. The position of those who advance nonpublic sectarian reasons in democratic deliberation is structurally bellicose, regardless of whether they argue in favor of a certain law or against it and regardless of their rhetoric.

Politics as competition

Those who accept PJP do not think that it is legitimate to impose their moral values on others by the coercive power of the state. Their concern is that under the conditions of deep moral disagreement social peace cannot be maintained on the presupposition that legitimacy is founded on moral truth, and morality is to be propagated by state coercion.Footnote 47

However, I would not hastily call the proponents of PJP the ‘party of peace’, because, obviously, political combatants also do not deny that peace is their ultimate goal. They just think that in order to enjoy peace they have to win the war first. Also, I would not rush to say that all and only those who accept PJP understand politics as a quest for civic friendship. Totalitarian political ideologies assume that the best way to maintain civic friendship is to get rid of all ‘enemies of the people’. So, ‘politics of friendship’ may be just the other side of politics as war. Another reason why I think the acceptance of PJP should not be identified with the pursuit of civic friendship is that I do not wish to support the view that politics aimed at consensus is bound to suppress any agonistic spirit within it.Footnote 48

PJP speaks not of actual acceptance of justificatory reasons by all, but of acceptance that may reasonably be expected. According to PJP, legitimacy is grounded in a possible consensus, not in a consensus that actually exists. Therefore, the principle does not exclude that legitimate legal provisions express a compromise or even a predominant public opinion that here and now has a significant number of dissenters. What PJP requires though, is that all actual legal provisions result from the pursuit of consensus.

The pursuit of consensus does not necessarily require that individuals downplay their own particular views in favor of some vague universal principles or for the sake of a pure fetish of friendship without any specific content to it. The mandatory pursuit of consensus does not mean that some perspectives are constantly suppressed in order for others to dominate in the name of solidarity and cohesion. It only means that no legal provision is enacted unless it has some non-sectarian justification. If citizens cannot inscribe their favorite dogmas directly into law and impose them on others by the coercive power of the state, it does not mean that they must relinquish all aspiration to advance their moral vision in the society. Public reason does not demand that we sacrifice the values that others reject, it only requires that we do not impose them on others. Obviously, it does not mean that we are not allowed to make our values and rules of conduct attractive to everyone.

PJP is only meant to ensure that one’s preferred rules are not turned into legal provisions unless one explicates their rationale in such a way that all may be able to see how everyone is going to benefit from them or how they will rectify some currently existing injustice. To this end, the requirement to pursue consensus does not allow to reduce the engagement in public dialog to mere reiteration of one’s favorite ideological dogma. As a result, members of the public are pushed to look for arguments that really have a chance of appealing to their opponents. Precisely in order to avoid the marginalization of diverse perspectives within the society, PJP requires that members of the public find the ways of expressing and defending their views that go beyond the canonized and ritualized argumentative practices of their communities. This is how different groups can reach across the ideological divides and actually engage with the perspectives of others, not just denounce or embrace them from the outset.

Citizens’ engagement in the public square does not have to be either a bitter quarrel or a celebration of civic bromance. It may also take the form of a competition in demonstrating the advantages of one’s preferred policies and legal provisions over those of the opponents. Depending on the depth of disagreement between the competitors, their contestation can become quite relentless. That is why they need a neutral state endowed with the coercive power to prevent the contestation from turning into a deadly war. If political competitors were to formulate “the first political question,” they would add one more item to Bernard Williams’s list.Footnote 49 They would say that the exercise of coercive political power must serve to maintain “order, protection, safety, trust, the conditions of cooperation” and competition. Competition is the form of peaceful engagement in the public square that PJP stimulates and secures, as it mandates the pursuit of consensus under the conditions of deep disagreement.

Finally, as PJP secures the conditions for peaceful political competition among citizens, its acceptance constitutes the first necessary step towards maintaining fair terms of cooperation across deep disagreement. By accepting PJP citizens put an end to politics as war. Accordingly, while citizens may still compete in trying to advance their values in the society, they no longer seek to dominate each other, which is obviously necessary for being able to cooperate on fair terms.

PJP meets the reflexivity requirement

Here we arrive at the crucial point in the justification of PJP. Those who reject PJP do not think that they must justify their preferred legal provisions to all members of the public. They act as political combatants who consider it morally inappropriate to refrain from legal enforcement of their moral vision throughout the society just because some of its members adhere to a different moral doctrine. Political competitors, on the contrary, abide by PJP and strike down as illegitimate all legislative offers and judicial decisions that fail to meet it. By doing so they exclude political combatants from the political competition. As a result, the ‘party of war’ finds itself at war with the ‘party of competition’. But it means only that political competitors treat political combatants in the way that the combatants may reasonably expect to be treated, given that the combatants treat their political opponents as enemies. It turns out that PJP treats both its adherents and opponents in accordance with their own understanding of how politics is to be done: political competitors are engaged in competition, political combatants are taken to war. Thus, even those who reject PJP on moral grounds have to recognize that it is fair.

The opponents of PJP would probably concede that this argument is valid for those political combatants who fully recognize everyone’s right to wage war against political opponents for whatever reasons one has. But, the objection might go, not all political combatants embrace such a radical conception of politics. Some of them believe that the exercise of political power is legitimate only if it is justified on the grounds of reasons that draw on true moral values. On this strictly moralistic view of politics, the enforcement of true moral values by the state is justified, while the opposition to such enforcement is not. As PJP blocks the enforcement of moral values by the state regardless of whether or not they are true, those political combatants who hold the strictly moralistic view of politics may not be reasonably expected to accept PJP.

This objection is rhetorically persuasive but misleading, because it attributes to my argument more than it actually tries to prove. I do not argue that the way politics is understood by political combatants requires them to accept PJP. I only argue that, having rejected PJP, political combatants may reasonably expect that political competitors will exclude them from the political competition. Also, I do not argue that the combatants must agree that this exclusion is morally right. On the contrary, given that political combatants understand all political disagreement as moral disagreement, it would be incoherent for them to recognize that the competitors’ opposition to the moralistic view of politics is morally right. Yet, the combatants must agree that it would be incoherent for the competitors to try to accommodate them in the legitimate political process, because the combatants actively negate what makes this process legitimate in the competitors’ view. Notably, political combatants do not even seek to be part of the consensus-oriented political competition, rather, they seek to put an end to it.

So, by excluding political combatants from the political competition, political competitors exercise politics in a way that everyone, even their opponents, may reasonably expect from them. On the contrary, it would be incoherent if political combatants started to complain about being excluded from the political competition — for they are not trying to compete at all. This would be like complaining about being punched and kicked out of a soccer match for punching and kicking other players. Soccer is just the kind of game where players are not allowed to punch and kick each other, and if you are acting otherwise, you are not trying to play soccer in the first place.

The soccer example helpfully illustrates that the coherence of PJP and incoherence of complaints from those who are excluded by it are not predicated on the commitment to the value of reciprocity, at least not necessarily so.Footnote 50 The counter-punches and exclusion from the soccer match do not have to be justified as some sort of reciprocal response to aggression or as a sanction for failing to show enough reciprocity in the game. Protecting the game from disruption and disincentivizing further aggression are by themselves good enough justifications for kicking the aggressive ‘players’ off the field.

Turning from the soccer analogy back to politics, I would argue that at the very basic level the value of reciprocity is not necessary for justifying PJP. Maintaining social stability, or peace, is already a serious enough purpose that cannot reasonably be dismissed. So, the most basic justification for the commitment to PJP may well be the pursuit of social peace, and my argument for PJP highlights that under the conditions of deep moral disagreement social peace is at stake when we decide whether to accept PJP or to reject it.

This is not to say, together with Hobbes, that “every man ought to endeavour peace.”Footnote 51 Nor would I say that under no circumstances can the pursuit of peace be morally overridden by the pursuit of some other values. But I would say that under any circumstances it is reasonable to use the coercive power of the state to contain the attempts to exercise politics as if it were, to use Rawls’s expression, “a relentless struggle to win the world for the whole truth.”Footnote 52

So, what does my ‘political choice argument’ actually say? The argument says that under the conditions of deep moral disagreement attempts to enforce morality by the coercive power of the state have inevitable consequences: your opponents will attempt to cease the political power from you in order to strike back. Some of them will do it because they reject your morality, others, like political liberals, will do it because they disagree with the enforcement. In short, if you are willing to impose your morality, prepare for politics as war. This argument presumes nothing that may not be reasonably expected from political actors, so there is nothing in it that they may not be reasonably expected to accept, regardless of whether they eventually choose to accept PJP or to reject it.

Thus, PJP is justified on the grounds of the distinction between politics as war and politics as competition that does not affirm any political and legal doctrines or moral values. It only offers an important political choice in a way that all may reasonably be expected to accept. Therefore, PJP meets its own criterion of legitimacy, it is self-applicable and not self-defeating.

Conclusion

I have defended the consensus-oriented public justification principle (PJP) from the self-defeat objection according to which the principle does not meet its own criterion of legitimacy because it is justified on the grounds of moral reasons that not all may reasonably be expected to accept.

I have argued, firstly, that there may be a discontinuity between morality and law, therefore, public justification of legal provisions and principles does not have to be a moral justification. Consequently, PJP may be justified as a legal-political principle even to those who oppose it on moral grounds.

Bearing this in mind, I argued, secondly, that the acceptance and rejection of PJP correspond to individuals’ basic views on the relation between politics and morality. Those who reject PJP think that it is right to impose their moral vision on the whole society through the use of the coercive state power by passing laws, carving out exemptions, and enforcing judicial rulings justified solely on the grounds of their comprehensive doctrines of the good, regardless of whether or not others may reasonably be expected to accept these doctrines. In a word, they understand politics as war. For those who accept PJP, using political power in order to impose one’s morality on others is wrong, so they declare illegitimate any legal provision that is supported solely by reasons that draw on some controversial moral, religious, or philosophical dogma. They understand politics as competition.

Given these distinctions, the maxim behind PJP is the following:

If you want politics to be a peaceful competition, do not impose your morality. Otherwise, prepare for politics as war.

The maxim describes the basic political choice and explicates the consequences of choosing between the two options. It does not tell what is the right choice, but, as I explained, choosing politics as competition entails PJP, which results in everyone being treated according to their own basic political choice: political competitors are engaged in competition, political combatants are excluded from competition and taken to war. That is why, regardless of its moral attractiveness, the consensus-oriented PJP is coherent and fair.

In a nutshell, if I accept PJP, I do it to avoid exercising politics as war. If I enforce PJP on those who exercise politics as war, I engage in a war that is unavoidable. Trying to avoid wars and engaging in wars that are unavoidable is reasonable even in the most ordinary sense of the word, in both cases I do what everyone may reasonably expect me to do. Thus, I have a justification for PJP that all may reasonably be expected to accept. PJP meets its own criterion of legitimacy, it is not self-defeating.

Notes

Charles Larmore, “Political Liberalism,” Political Theory 18 (3) (1990): pp. 339–360; John Rawls, Political Liberalism. Expanded Edition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), pp. 137, 217, 226, 243, 393.

Joseph Raz, “Disagreement in Politics,” American Journal of Jurisprudence 43 (1) (1998): pp. 25–52; Steven Wall, “Is Public Justification Self-Defeating?” American Philosophical Quarterly 39 (4) (2002): pp. 385–394; David Enoch, “The Disorder of Public Reason,” Ethics 124 (1) (2013): pp. 141–176, at pp. 170–173; Franz Mang, “Public Reason Can Be Reasonably Rejected,” Social Theory and Practice 43 (2) (2017): pp. 343–367; Fabian Wendt, “Rescuing Public Justification from Public Reason Liberalism,” in D. Sobel, P. Vallentyne, and S. Wall (eds.), Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy 5 (2019), pp. 39–64, Section 5.

Gerald Gaus, The Order of Public Reason: A Theory of Freedom and Morality in a Diverse and Bounded World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 226–228; Sameer Bajaj, “Self-Defeat and the Foundations of Public Reason,” Philosophical Studies 174 (12) (2017): pp. 3133–3151.

Kevin Vallier, “Public Reason Is Not Self-Defeating,” American Philosophical Quarterly 53 (4) (2016): pp. 349–363.

David M. Estlund, Democratic Authority: A Philosophical Framework (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), pp. 53–64; Jonathan Quong, Liberalism without Perfection (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 291; Andrew Lister, Public Reason and Political Community (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 127; idem, “The Coherence of Public Reason,” Journal of Moral Philosophy 15 (2018): pp. 64–84, at pp. 74–83.

What I address here intersects with Kevin Vallier’s recent work on how public reason might help to prevent politics from turning into ‘war by other means’ (Kevin Vallier, Must Politics Be War? Restoring Our Trust in the Open Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)). However, his discussion is different from mine in at least two important aspects. First, he defends the convergence model of public justification, while this paper defends the consensus model. Second, he seeks to “derive a political constitution from the justification of a society’s moral constitution” (Ibid., p. 11), while this paper remains skeptical about the desirability of such an endeavor.

Raz, “Disagreement in Politics,” p. 30.

Rawls, Political Liberalism, pp. 217, 393.

Ibid., pp. 49, 375.

Estlund, Democratic Authority, pp. 53–55.

Quong, Liberalism without Perfection, p. 291.

Lister, Public Reason and Political Community, p. 127; also see R. J. Leland, “Civic Friendship, Public Reason,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 47 (1) (2019): pp. 72–103.

Mang, “Public Reason Can Be Reasonably Rejected,” p. 356.

One way to show that the justificatory reasons for PJP are reasonably acceptable to its liberal opponents is to point out that there are at least two possible interpretations of the acceptability requirement that are compatible with the consensus-oriented view of public reason. On this view, ‘reasonably acceptable’ reasons may be understood either as ‘shareable’ reasons or as ‘accessible’ reasons. (See Kevin Vallier, “Public Justification,” in ed. Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed 28 April 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/

justification-public/.) Shareable reasons are those that all members of the public are epistemically entitled to hold according to a common evaluative standard. Accessible reasons are those that the reason-givers, but not necessarily all members of the public, are epistemically entitled to hold according to a common evaluative standard. Unless it is explicitly denied that PJP is compatible with liberal political values, justificatory reasons for PJP that draw on these values may well be accessible to its liberal opponents, if not shareable by them. So, apparently, at least one particular interpretation of the consensus-oriented PJP unequivocally meets its own standard of justification vis-à-vis liberal perfectionist opposition.

Mang, “Public Reason Can Be Reasonably Rejected,” p. 362.

Larmore, “Political Liberalism”; Rawls, Political Liberalism, pp. 36, 144; Quong, Liberalism without Perfection, pp. 37, 139–140, 233; James W. Boettcher, “Respect, Recognition, and Public Reason,” Social Theory and Practice 33 (2) (2007): p. 223–249; idem, “The Moral Status of Public Reason,” Journal of Political Philosophy 20 (2012): pp. 156–177.

Boettcher, “Respect, Recognition, and Public Reason,” p. 232.

Han van Wietmarschen, “Political Liberalism and Respect,” Journal of Political Philosophy, forthcoming, Section V.

Wall, “Is Public Justification Self-Defeating?” p. 390.

Steven Wall, “Public Reason and Moral Authoritarianism,” Philosophical Quarterly 63 (250) (2013): pp. 160–169.

Here I discuss a possible way of showing that RR does not apply to the consensus-oriented PJP. There is an alternative, convergence model of public justification. In this model a coercive law is publicly justified if all members of the public consider it an improvement judging by their own evaluative standards that do not have to be shareable by all (Gerald Gaus and Kevin Vallier, “The Roles of Religious Conviction in a Publicly Justified Polity: The Implications of Convergence, Asymmetry and Political Institutions,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 35 (1-2) (2009): pp. 51–76, at pp. 56–58, 70; Gaus, The Order of Public Reason, pp. 497–506). The convergence-oriented public justification principle is applied, as Lister puts it, “at the level of laws and not at the level of reasons,” which makes it inapplicable to itself (Lister, Public Reason and Political Community, p. 125; idem, “The Coherence of Public Reason,” pp. 71–73). Meanwhile, the consensus-oriented PJP is applied at the level of justificatory reasons, and the principle itself may be used as a justificatory reason for rejecting a law. Thus, if there is a way to show that the consensus-oriented PJP does not necessarily apply to itself, it is not the same as the one that works for the convergence model.

See a similar argument in Gaus, The Order of Public Reason, pp. 226–8.

Bajaj, “Self-Defeat and the Foundations of Public Reason.”

Ibid., p. 3145.

Vallier, “Public Reason Is Not Self-Defeating,” p. 360.

Ibid., p. 335.

Ibid., p. 356.

Ibid., p. 356.

Ibid., “Public Reason Is Not Self-Defeating,” p. 351.

Estlund, Democratic Authority, pp. 53–64.

Lister, Public Reason and Political Community, p. 127; idem, “The Coherence of Public Reason,” pp. 74–83.

Lister, Public Reason and Political Community, p. 116.

Ibid., p. 127.

Rawls, Political Liberalism, pp. 49, 375.

Ibid., pp. 56–58, 247.

John Rawls, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2001), p. 87.

Bernard Williams, In the Beginning Was the Deed: Realism and Moralism in Political Argument (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), p. 3.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, IV, 4.

Jonathan Leader Maynard, and Alex Worsnip, “Is There a Distinctively Political Normativity?” Ethics 128 (4) (2018): pp. 756–787.

Fabian Wendt, “Peace beyond Compromise,” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 16 (4) (2013): pp. 573–593, at p. 578.

Cf. Fabian Wendt, Compromise, Peace, and Public Justification: Political Morality beyond Justice (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), pp. 23–30.

Martha C. Nussbaum, “Liberty of Conscience: The Attack on Equal Respect,” Journal of Human Development 8 (3) (2007): pp. 337–357, at p. 342.

“Slovo Svyatejshego Patriarcha…” Patriarchia.ru, March 21, 2016. Accessed September 14, 2020. http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/4410951.html.

For example, see how legal positivism’s main thesis is formulated in H. L. A. Hart, Essays in Jurisprudence and Philosophy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983), p. 55.

Enzo Rossi, and Matt Sleat, “Realism in Normative Political Theory,” Philosophy Compass 9 (10) (2014): pp. 689–701, at p. 689.

Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975–1976. Translated by D. Macey. (New York: Picador, 2003), p. 15.

Here I paraphrase John Locke, “A Letter Concerning Toleration,” in Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), p. 226: “No peace and security, no, not so much as common friendship, can ever be established or preserved amongst men, so long as this opinion prevails, ‘that dominion is founded in grace, and that religion is to be propagated by force of arms’.” I thank the anonymous Reviewer for drawing my attention to this particular passage in Locke.

Cf. Chantal Mouffe, The Democratic Paradox (London: Verso, 2000), pp. 6–9, 22–34.

Williams, In the Beginning Was the Deed, p. 3.

I thank the anonymous Reviewer for pressing me to clarify how my defense of PJP against the self-defeat objection differs from Lister’s reciprocity-based defense.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 87; on the conceptual links between Hobbes’s “general rule of reason” and Rawls’s idea of public reason see S. A. Lloyd, “Learning from the History of Political Philosophy,” in J. Mandle and D. A. Reidy (eds.), A Companion to Rawls (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2014), pp. 526–545, at pp. 538–540; cf. Gerald Gaus, “Hobbes’s Challenge to Public Reason Liberalism: Public Reason and Religious Convictions in Leviathan,” in S. A. Lloyd (ed.), Hobbes Today: Insights for the 21st Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 155–177. I thank another anonymous Reviewer for suggesting that I comment on the apparent affinity between my defense of PJP and Hobbes’s “general rule of reason.” I do not state categorically that people ought to pursue peace. I only argue that if people do not pursue peace, they are not in a good position to complain that they do not get it.

Rawls, Political Liberalism, p. 442.

Acknowledgements

I thank Sameer Bajaj, Richard Bellamy, Ferran Requejo, Giorgi Tskhadaia, and two anonymous Reviewers for their comments and criticism, from which this article has greatly benefited.

Funding

The author is a WIRL-COFUND Fellow in the Institute of Advanced Study at the University of Warwick. These fellowships were supported by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under the Marie Skłodowska Curie Actions COFUND programme (Grant Agreement No. 713548).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bespalov, A. Against Public Reason’s Alleged Self-Defeat. Law and Philos 40, 617–644 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10982-021-09418-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10982-021-09418-6