Abstract

Context

Community composition, environmental variation, and spatial structuring can influence ecosystem functioning, and ecosystem service delivery. While the role of space in regulating ecosystem functioning is well recognised in theory, it is rarely considered explicitly in empirical studies.

Objectives

We evaluated the role of spatial structuring within and between regions in explaining the functioning of 36 reference and human-impacted streams.

Methods

We gathered information on regional and local environmental variables, communities (taxonomy and traits), and used variance partitioning analysis to explain seven indicators of ecosystem functioning.

Results

Variation in functional indicators was explained not only by environmental variables and community composition, but also by geographic position, with sometimes high joint variation among the explanatory factors. This suggests spatial structuring in ecosystem functioning beyond that attributable to species sorting along environmental gradients. Spatial structuring at the within-region scale potentially arose from movements of species and materials among habitat patches. Spatial structuring at the between-region scale was more pervasive, occurring both in analyses of individual ecosystem processes and of the full functional matrix, and is likely to partly reflect phenotypic variation in the traits of functionally important species. Characterising communities by their traits rather than taxonomy did not increase the total variation explained, but did allow for a better discrimination of the role of space.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the value of accounting for the role of spatial structuring to increase explanatory power in studies of ecosystem processes, and underpin more robust management of the ecosystem services supported by those processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological processes that regulate the retention and flux of energy and nutrients are central to the functioning of ecosystems, and the services ecosystems provide society (Truchy et al. 2015). Ecosystem functioning can be defined as “the joint effects of all processes [fluxes of energy and matter] that sustain an ecosystem” (Naeem and Wright 2003) over time and space through biological activities. Concern that environmental degradation is compromising important ecosystem processes and the services they support has stimulated research into the factors regulating ecosystem functioning along both natural and anthropogenic gradients (Von Schiller et al. 2008; Frainer et al. 2017). Usually, functioning is quantified as one or more ecosystem-level process rates, such as primary production or litter decomposition (Gessner and Chauvet 2002; Srivastava and Vellend 2005), with variation in these processes often explained by abiotic (e.g. temperature, moisture, soil chemistry) and biotic (e.g. community composition, biodiversity) variables, all quantified at local scales. In contrast, although well recognised in theory, the role of spatial structure, arising from the spatial distribution of key species or habitats (Schmitz 2010), the movements of organisms among habitat patches (Loreau et al. 2005), or larger scale variation in species phenotypes (Ashton et al. 2000), as a regulator of ecosystem functioning at local scales is rarely considered explicitly in empirical studies (Pringle et al. 2010). This is a key shortcoming, given the extent to which human activities are currently altering the distribution of species and linkages between habitats and ecosystems at multiple spatial scales (Heffernan et al. 2014).

Multiple forms of structuring in the spatial distribution of species and habitats, species characteristics, and behaviours have the potential to influence ecosystem functioning at local scales. Firstly, species and the processes they regulate are often sorted at local scales along gradients in key environmental factors, which both influence the suitability of habitat patches for different species and regulate organism activity rates (Leibold et al. 2004; Venail et al. 2010). For example, the key ecosystem process of litter decomposition often varies along gradients in pH, since low pH not only reduces diversity of decomposer organisms, but also suppresses the activity of key fungi that drive the enzymatic hydrolysis of leaf litter (McKie et al. 2006). Secondly, as posited by meta-ecosystem theory, the movements of species, nutrients, and materials among habitat patches might also impose spatial structure on ecosystem functioning (Loreau et al. 2005). For instance, source-sink dynamics underpinning “mass-effects” in organism movements might contribute to maintenance of ecosystem functioning in a local “sink” habitat patch through ongoing immigration of essential species for particular ecosystem processes. Similarly, transfers of nutrients and energy across habitat boundaries or within ecological networks can result in spatial subsidization of ecosystem processes in recipient ecosystem, as seen in the patchy subsidization of terrestrial food webs by the emerging adult stages of aquatic insects (Burdon and Harding 2008; Carlson et al. 2016). Thirdly, the model of “self-organized systems” posits that organization in the spatial distribution of keystone or foundational species arising from interspecific interactions can also drive predictable spatial structuring in ecosystem functioning (Schmitz 2010; Dong and Fisher 2019). This is seen in African savannah habitats, where the evenly spaced distribution of termite mounds creates a spatial matrix in soil humidity, aeration, and nutrient content, which are all enhanced in the vicinity of termite mounds, and which in turn promote predictable structuring in biodiversity and productivity of both plants and invertebrates (Pringle et al. 2010). Finally, variation in species phenotypes might drive substantial spatiotemporal variability in the importance of particular species and communities for ecosystem functioning (Lecerf and Chauvet 2008; Des Roches et al. 2018). Latitudinal variation in intraspecific body size (Ashton et al. 2000; McKie and Cranston 2005) is particularly likely to alter the importance of particular species for functioning over large scales, given the importance of biomass as a key driver of ecosystem processes (Brown et al. 2004; Hildrew et al. 2007; Perkins et al. 2010).

In practice, most studies investigating spatial variation in ecosystem functioning evaluate the joint variation of ecosystem processes and biodiversity along easily quantified environmental gradients in, for example, nutrients, temperature and habitat structures (Young and Collier 2009; Frainer et al. 2017). Accordingly, the environmental sorting model is, by default, the dominant paradigm through which spatial structuring in ecosystem functioning is understood. In contrast, isolating how spatial patterns in functioning are shaped by biotic interactions, meta-ecosystem processes, and phenotypical variation in species behaviour is a major practical challenge. Such efforts are most likely to occur in studies focused on small scale impacts of key species and interactions, movements of organisms and materials, and intraspecific variability in traits (Pringle et al. 2010; Logue et al. 2011). However, even where more detailed investigations into the particular mechanisms underlying spatial structuring of ecosystem functioning are not logistically feasible, as is often the case in routine biomonitoring, quantification of the portion of variation attributable to spatial structuring might still yield insights relevant for management. For example, management that targets the impacts of an anthropogenic stressor on local-scale ecosystem functioning might only be partially effective if a significant portion of variation in functioning is attributable to the interactions and movements of organisms and materials among habitat patches, and/or phenotypic variation in species phenotypes. In such cases, further research into the mechanisms underpinning spatial structuring, and the interplay between spatial structuring and environmental and biotic variation at local scales, is needed to underpin the development of more efficient management.

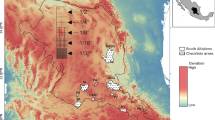

Here we ask how much of the variability in ecosystem functioning among 36 boreal streams distributed across three regions in Sweden can be attributed to their spatial location (i.e. geographic position) relative to environmental characteristics and community composition. The three regions spanned a distance of 770 km between the southernmost (boreonemoural ecoregion, mean annual temperature 6.6 °C) and the northernmost (in the middle boreal ecoregion, mean annual temperature 1.5 °C) sites. We further evaluate whether spatial structuring occurs predominantly within or between regions. Our study systems ranged from forested reference sites to streams strongly impacted by human activities, allowing an assessment of the importance of spatial structuring when environmental parameters vary under anthropogenic influence. We used variance partitioning analysis to assess how much variation in a matrix of seven functional metrics was explained by the unique and joint effects of (i) environmental variables and (ii) the community composition of four organism groups (invertebrates, diatoms, macrophytes, and fish), as well as geographic position of the streams, which were used to evaluate the role of spatial structuring separated into (iii) within- and (iv) between-region spatial components. We conducted additional analyses where key organism groups were scored according to their functional traits rather than taxonomic identities. Such traits represent the phenotypic attributes of an organism that regulate its responses to environmental factors (e.g. thermal tolerances, life history strategies) and its influences on ecosystem processes (e.g. feeding rates, feeding mode) (Naeem and Wright 2003; Violle et al. 2007; Truchy et al. 2015). According to Grime’s mass-ratio hypothesis (Grimes et al. 1998), ecosystem functioning is likely to vary according to the dominant traits in an assemblage, and as such characterisation of species according to their traits is posited to increase explanatory power in studies relating communities and ecosystem functioning (Enquist et al. 2015; Gagic et al. 2015). We assessed the following general hypotheses.

-

(1)

The unique and shared effects of environmental and community composition variables together explain more variation in ecosystem functioning than geographic position, reflecting the sorting of species according to environmental characteristics, and the role of environment and community characteristics in regulating ecosystem processes.

-

(2)

Additionally, some variation in ecosystem functioning is also attributable to geographic position, reflecting the potential for spatial structuring to arise from mechanisms other than species sorting along environmental gradients.

-

(3)

We expect strong spatial structuring at the between region scale, due to the likelihood that differences in species phenotypes across regions alter the impacts of communities on functioning. We further expect that spatial structuring of ecosystem functioning occurs within-regions, due to the potential for both meta-ecosystem and self-organisation mechanisms to influence functioning at this scale.

-

(4)

The use of species traits will increase explanatory power, compared to the characterisation of communities by their taxonomic identities alone, in line with Grime’s hypothesis that the effects of biota on functioning are driven by the dominant traits in the community.

Methods

Study sites

We quantified biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and environmental variables in 36 streams across three distinct regions in Sweden (Appendix 1, Fig. S1.1) using identical protocols across all regions and stream reaches. Within each region, we sampled 2nd–3rd order stream reaches that drain forested ‘reference’ catchments, as well as streams that are more heavily impacted by human activities. This design insured inclusion of strong environmental gradients within and among regions (Appendix S1, Fig. S1.1). The major anthropogenic pressure in each region varied, with agriculture, hydropower, and forestry activities dominating in the southern, central, and northern regions, respectively.

Conceptual figure summarizing the types of explanatory variables (boxes) that were included in our analyses to explain variation in ecosystem functioning (the response depicted as a circle). Ecosystem functioning of 36 streams was assessed by measuring seven different ecosystem processes. Environmental variables consisted of properties quantified at each sampled stream reach (e.g. water chemistry) together with information on catchment land use, which strongly impacts local environmental conditions. Community composition encompassed data on benthic diatoms, macrophytes, macroinvertebrates and fish, represented either as species abundances or functional traits in our different analyses. Environmental and community variables were collapsed to fewer dimensions (principal component (PC)) through principal component analysis (PCA). Space was accounted for using the geographical coordinates of the sampling sites and the regions to which the site belong to (3 distinct regions were included in the study). Spatial scales were represented as Moran’s eigenvector maps (MEM). Significant PC and MEM were selected with a forward selection procedure before being used in the variance partitioning analysis

Ecosystem functioning

We quantified a set of seven indicators of ecosystem functioning using well-defined and recognised methods (Lamberti and Resh 1983; Benfield 1996; Gessner 2005; Dietrich et al. 2013) (see Appendix S2 for detailed descriptions). Five were direct measures of basal ecosystem processes in freshwater food webs: (1) the biomass accrual of primary producers in algal biofilms, (2) the decomposition of terrestrial detritus by the full decomposer assemblage and (3) by microbial decomposers only, and (4) the biomass accrual of aquatic fungi on litter in the presence and (5) absence of invertebrate detritivores (i.e. coarse vs. fine meshed litterbags). We quantified two further variables to capture the functioning of additional food web compartments: (6) the biomass accrual of an aquatic bryophyte (Fontinalis dalecarlica), as a macrophyte “phytometer”, and a measure of (7) fine particulate organic matter (FPOM) deposition (Appendix S2). Each indicator captures distinct aspects of stream food webs that can be differently affected by local and regional scale community and environmental variation. For instance, decomposition of terrestrial detritus and algal productivity are regulated not only by community composition and stream flow characteristics at local scale, but also potentially by subsidies of nutrients and other materials (including leaf litter) from surrounding catchments (McKie et al. 2008; Von Schiller et al. 2008). These processes may be additionally influenced by the presence of barriers (e.g. dams) which might hinder the free movement of key organisms contributing directly to the process itself (e.g. detritivores or algal species) or impacting those organisms (e.g. predators).

Biotic sampling and environmental predictors

Primary producers (benthic diatoms and macrophytes) and consumers (benthic invertebrates and fish) were sampled once in each stream reach following European/Swedish standard methods (Naturvårdsverket 2003, 2010) (see Appendix S3 for a detailed description of the sampling methods). We also compiled a comprehensive dataset on potential environmental drivers of community composition and stream ecosystem functioning, including catchment land use (a strong driver of local habitat conditions), and stream physical and chemical variables quantified during our field study at each stream reach (Fig. 1; see Appendix S1, Table S1.1 for a detailed list of the parameters included in the study).

Species traits

Trait information was retrieved for two taxonomic groups: fish traits were extracted from the “Freshwaterecology.info” database (Schmidt-Kloiber and Hering 2015), while invertebrate traits came from Tachet et al. (2010). For both groups, we focused on traits that are closest in their definition to true functional effect traits (Truchy et al. 2015) (Appendix S2, Table S2.1), i.e. most likely to be correlated with the effects of organisms on ecosystem processes (Hooper et al. 2002; Lavorel and Garnier 2002; Naeem and Wright 2003). We compiled a set of traits that represents not only the likely direct influences of organisms on our functional measures (e.g. feeding preferences, body size), but also habitat-use and phenological traits regulating where and when different species are likely to be most active in their influences on function (Frainer et al. 2014) (Appendix S2, Table S2.1). Additionally, we quantified the body lengths of litter-consuming invertebrates (a functional guild known as “shredders”) found colonising our litter bags to the nearest mm, and converted these length measures into biomass estimates, based on formulae from Meyer (1989).

Data analyses

All analyses were performed in the R environment (R Core Team 2018).

We used Moran’s Eigenvector Maps (MEM) to model spatial structuring of our ecosystem functioning data (Borcard and Legendre 2002; Legendre and Legendre 2012). Our spatial model consisted of two components (Fig. 1): (i) a B-component, representing region identity using a dummy variable, and (ii) a W-component, consisting of MEM describing the spatial structuring among streams within a region, based on Euclidean distances (i.e. geographical distances). Euclidean distances were the most appropriate to represent our study design, which comprised streams situated in three distinct regions that were not strongly connected hydrologically (i.e. no sampling station was situated downstream of another). MEM analyses produce a set of orthogonal spatial variables derived from the geographical coordinates of the study sites (Dray et al. 2006). The approach used here was a sophisticated version of the MEM analysis using the function “create.MEM.model” developed by Declerck et al. (2011), for which we specified the site coordinates and the region. The within-region spatial structures in the dataset were taken into account using this approach, as the sites in the other two regions get zero values when the spatial structure within a given region is considered (Declerck et al. 2011). This analysis results in a staggered matrix of MEM eigenvectors. We then selected the significant MEM with a forward selection procedure (Blanchet et al. 2008) (function “forward.sel” in the R package packfor (Dray et al. 2013).

To account for environmental variation and community effects on ecosystem functioning, environmental and community variables (i.e. abundances or traits) were first collapsed to fewer dimensions using principal component analysis (PCA) in which the variables were centred and standardised, using the R package ade4 (Dray and Dufour 2007) (Fig. 1). The species abundance matrices were Hellinger-transformed prior to running the PCA (Legendre and Gallagher 2001) while the trait matrices for fish and invertebrates were represented by community weighted means (CWM) calculated as: \( \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {relative\,abundance_{i} \times trait_{i} } \) (for a species i, Lavorel et al. (2008)). Therefore, final matrices of environmental and community variables consisted of site scores along principal components (PC) that were also selected using a forward selection procedure (Fig. 1). This procedure ensured that all explanatory variables were given equal weights in our variance paritioning analyses (see below).

We used variance partitioning (VP) analyses to separate variation in ecosystem functioning explained by spatial structuring at the between- and within-region scales (B- and W-components), from that explained by our environment (E) and community composition (C; as abundances or traits) matrices. The VP method allows partitioning the variation attributable purely to single sets of variables from the shared variation of two or more sets of variables (Borcard and Legendre 2002). We used the function “varpart” from the R package vegan (Oksanen et al. 2015).

We conducted four types of variance partitioning analysis, denoted hereafter as VP sets 1–4. In sets 1–2, we systematically assessed variation in the entire functional matrix when accounting for all organism groups together (VP1), followed by analyses for each functional indicator separately (VP2), since different indicators may vary in the degree to which they are regulated by environmental, biotic and spatial factors:

-

VP1: a single analysis that partitioned spatial variation associated with the between- (B), within-region (W) scales from that associated with the abiotic environment (E) and community composition (Cc), on the complete ecosystem functioning matrix (i.e. including all seven functional indicators), and conducted using community data for all four biological groups combined. The variables in the ecosystem functioning matrix were standardized to mean = 0 and SD = 1 prior to analysis.

-

VP2: comprised seven analyses that were identical to the VP1 analyses, except they were conducted for each functional indicator separately rather than the complete functional matrix. As only one response variable was analysed at a time, no standardization was applied in these analyses.

In sets 3–4, we analysed variation in the entire functional matrix, but with each organism group fitted separately, since particular organism groups might differ in their importance for combined functioning (VP3). We further evaluated the explanatory power of species traits as a substitute for taxonomic identities in the community matrices for two organism groups (VP4). In all these analyses, variables in the ecosystem functioning matrix were standardized to mean = 0 and SD = 1.

-

VP3: comprised four analyses identical to that of VP1, except that they were conducted for each biological group (i.e. diatoms, macrophytes, macroinvertebrates and fish) separately.

-

VP4: comprised two analyses that were identical to VP3 analyses, except that community composition was quantified on the basis of species traits (Ct) rather than species abundances, separately for the two biological indicators for which adequate trait information was available, viz. fish and invertebrate traits.

We tested for the significance of our global models that include the explanatory variables selected with the forward selection procedure; and then tested for the significance of the unique fractions B, W, C and E using the function “rda” from the package vegan (Oksanen et al. 2015). It is not possible to test the significance of shared variation.

Results

VP1: importance of spatial scales for stream ecosystem functioning

In our partitioning of the entire functional matrix and including information on all organism groups, spatial structuring at two spatial scales (B- and W-components), communities and environment together explained 52% of the total variation (P < 0.001). The within-region spatial component, community composition, as well as environment explained significant unique fractions of variation (Fig. 2), while 18% of the variation in ecosystem functioning was explained jointly between community composition and environment.

Venn diagram showing variation in ecosystem functioning in 36 streams explained by four sets of explanatory variables: between- (B; in magenta) and within- (W; in blue) region spatial components, community composition (Cc; in yellow) and environment (E; in green) and their joint effects (the overlapping parts of the circles represented as ∩). The four community groups are fitted together. Sets of explanatory variables that do not significantly explain any important fraction of variation in ecosystem functioning (P > 0.05 or adjusted R2 ≤ 0.05) are coloured in grey tones. For each testable fraction, an adjusted R2 is given and P ≤ 0.05 are indicated in regular font while P < 0.1 are in italics. The residual variation that was not explained by the variance partitioning analysis is reported in the right hand corner. The size of the circles is proportional to the effects of the set of explanatory variables, the bigger the circle the greater the importance of this set of explanatory variables in explaining variation in ecosystem functioning. (Color figure online)

VP2: partitioning the individual functional indicators

When analysing each functional indicator separately, no significant variation was explained for either bryophyte biomass accrual or FPOM dynamics. For the remaining five functional indicators, the total amount of variation explained was high, ranging from 47% (fungal biomass accrual in coarse mesh bags) to 83% (algae biomass accrual) (Table S4.1).

Unique fractions of variation were explained by the between-region spatial component for algal biomass accrual and litter decomposition, and by community composition for all processes (Table S4.1). Unique fractions of variation explained by the environment were only significant for litter decomposition (Table S4.1). Variation explained jointly by community composition and environment ranged from 25% (fungal biomass accrual in fine mesh bags) to 48% (litter decomposition in fine mesh bags). Variation explained jointly by the within-region component and community composition was as high as 17% for fungal biomass accrual in coarse mesh bags (Table S4.1). Finally, the shared fraction explained by the between-region spatial component, community composition and environment was high for algal biomass accrual (38%).

VP3: importance of different organism groups for stream ecosystem functioning

When fitting the four community groups separately, the total variation in ecosystem functioning explained by the predictor matrices ranged from 44% (diatoms) to 54% (fish) (Table S4.2; Fig. 3a, c; all P < 0.001). The unique fractions explained by the predictors were all significant when fitting diatom and fish abundances as community matrices (Table S4.2; Fig. 3c). The between-region spatial component was not significant when fitting macrophyte and invertebrate communities (Table S4.2; Fig. 3a). The within-region spatial component was significant or nearly so in all analyses. The between- and within-region spatial components have shared effects with community composition in the diatom analysis only (Table S4.2). The joint variations associated with the spatial scales (B or W) were always small (ranging from 0.9% to 5%, Table S4.2; Fig. 3a, c), regardless of which taxonomic group was fitted as the community matrix. However, the joint variation explained by the community matrices and the environment was always higher (ranging from 8% when fitting macrophytes to 18% when fitting invertebrates, Table S4.2; Fig. 3a, c), regardless of which taxonomic group was fitted as the community matrix.

Venn diagrams showing variation in ecosystem functioning in 36 streams explained by four sets of explanatory variables: between- (B; in magenta) and within- (W; in blue) region spatial components, environment (E; in green), and community composition (in yellow) of either invertebrates (I; a, b) or fish (F; c, d), and their joint effects (the overlapping parts of the circles represented as ∩). Community composition was fitted as either species abundances (Ic or Ft; a, c) or species traits (It or Ft; b, d). Sets of explanatory variables that do not significantly explain any important fraction of variation in ecosystem functioning (P > 0.05 or adjusted R2 ≤ 0.05) are coloured in grey tones. For each testable fraction, an adjusted R2 is given and P ≤ 0.05 are indicated in regular font while P < 0.1 are in italics. The residual variation that was not explained by the variance partitioning analysis is reported in the right hand corner. The size of the circles is proportional to the effects of the set of explanatory variables, the bigger the circle the greater the importance of this set of explanatory variables in explaining variation in ecosystem functioning. (Color figure online)

VP4: incorporating species traits

Traits of invertebrates and fish combined with spatial scales and environment explained 38% to 41%, respectively, of variation in ecosystem functioning (Fig. 3b, d). Unique fractions were associated not only with spatial scales and environment, but also with the composition of species traits for fish only (Fig. 3d). Variation explained jointly by the species traits and environment matrices was 15% when fitted with invertebrate traits (Fig. 3b). The other joint fractions explained were either marginal (ranging from 0.1 to 4%) or not testable (negative R2).

Discussion

In line with our hypotheses, variation in our matrix of multiple functional indicators was explained not only by environmental variables and community composition, but also by the geographic position of our study reaches. This indicates significant spatial structuring in ecosystem functioning, beyond that attributable to the sorting of species and the processes they regulate along environmental gradients. Spatial structuring of ecosystem functioning was found at the between-region scale, suggesting local ecosystem functioning was structured by larger scale spatial variation likely to reflect differences in the phenotypes of functionally important species. Additionally, significant spatial structuring was often apparent within regions, potentially arising from the connectivity of species and materials among habitat patches and/or associated with self-organisation of particular key species. Overall, the proportion of variation in ecosystem functioning explained by our environmental and community matrices did not exceed that explained purely by spatial structuring, and the joint variation among these factors was sometimes high (up to 48%). Finally, contrary to our expectations, the use of traits rather than taxonomic identities did not improve the amount of variation explained. Nevertheless, the use of traits did allow better discrimination of the role of space.

Environment and community composition explain greater amounts of variation in ecosystem functioning

Our variance partitioning based on matrices of environment, community composition, and spatial scales (both between- and within-regions) was able to explain a relatively high proportion (52%) of total variation in ecosystem functioning, compared with most studies partitioning the influence of space and environment on community composition (Grönroos et al. 2013; Heino et al. 2015). Moreover, unique environmental effects were often significant, supporting the idea that stream ecosystems and their communities are generally under strong abiotic control (Reice 1994; Johnson et al. 2004), as found in variance partitioning analyses of community composition (e.g. Pinel-Alloul et al. 1995; Göthe et al. 2013; Grönroos et al. 2013). However, the shared variation between the environmental and community matrices were sometimes as high as 48% in our study. This suggests that environmental effects on functioning are often mediated through effects on community composition (Jonsson 2006; O’Connor and Donohue 2013; Törnroos et al. 2015), such that not only species and communities but also the processes they regulate frequently sort along environmental gradients. This indicates that intermediary impacts of environmental variation on ecosystem processes via biotic interactions, behaviour, and trait expression are at least as important as those reflecting direct abiotic control (McKie et al. 2009; Brose and Hillebrand 2016).

Spatial structuring of ecosystem functioning occur between- and within-regions

Our analyses were able to partition variation associated with spatial structuring at two scales, but we are not able to definitively isolate the underlying causal processes. Spatial structuring at the between-region scale occurred in analyses focussing on specific organism groups (e.g. diatoms, fish), and was the only unique fraction of spatial structuring detected in analyses of each individual functional indicator (VP2). This structuring is most likely to arise from variation in characteristics of the local stream environments and species phenotypes that were (i) not well-represented in our sampling scheme and/or (ii) strongly confounded with the larger between-region scale, and thus was captured by our spatial components rather than environmental or community matrices (e.g. different vegetation zones in a single region (Ahti et al. 1968)). The degree of variability in environmental variables is subject to large scale gradients (e.g. latitudinal gradients in diel light and temperature regimes, or in timing of inputs of resources such as leaf litter), and can differ strongly among regions as a result of shifting precipitation, vegetation, land cover and/or geology (Ahti et al. 1968; Hillebrand 2004; Sponseller et al. 2014). Our environmental data comprised a comprehensive set of variables routinely measured in studies of stream ecosystem functioning, but mostly quantified as mean values derived from a limited number of sampling events, and it is thus likely that we missed much of this variability. Large scale environmental variation also drives divergence in species phenotypes (McKie and Cranston 2005; Boyero et al. 2017). For example, our northern sites experience 2 h less of complete night time darkness in early September than the southernmost sites (Raab and Vedin 1995), a difference which might have implications for the phenotypes and activity patterns of primary producers, consumers, and the processes they mediate. Notably, many of the traits that have been identified as most useful for characterising linkages between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in ecological networks—such as growth rates, body size and resource use rates (Brose and Hillebrand 2016)—are also highly plastic, and particularly subject to regional variation in thermal regimes and composition of the resource base. Fortunately, many of these relationships are also highly predictable (Ashton et al. 2000; McKie and Cranston 2005; Boyero et al. 2017), highlighting the potential of developing more finely tuned and spatially explicit trait classification schemes that embed relationships between important spatial and environmental attributes (e.g. latitude, degree days, nutrient concentrations) and values for traits such as body size and growth rates.

The unique fraction of spatial structuring within-regions was only significant in analyses that partitioned variation in all functional indicators, such as the analysis including all organism groups (VP1), and those focussing on diatom communities (VP3) and fish and invertebrate species traits (VP4). These tests are imperfect assessments of the true importance of spatial structuring at a given scale, since they do not account for shared fractions of variation. Nevertheless, these results do indicate that spatial structuring is most likely to emerge at smaller, within-region scales when multiple ecosystem processes, potentially regulated by multiple flows of organisms, nutrients and energy within and across habitat boundaries, are considered simultaneously. This potentially reflects the role of meta-ecosystem processes, including mass-effects governing flows of organisms and materials (nutrients, carbon, etc.), which are more likely to have influenced spatial structuring within- than between-regions, owing to greater spatial proximity and potential connectedness of sites at this scale (Leibold et al. 2004; Cottenie 2005; Logue et al. 2011). It is less likely that spatial structure arising from self-organisation of keystone or foundational species underpins within-region spatial variation in our study, since our studied processes are not clearly dependent on such species, and environmental heterogeneity among our study reaches was likely too great to have favoured self-organisation arising from intraspecific interactions (e.g., Cornacchia et al. 2018; Widenfalk et al. 2018). It is also possible that spatial structuring within regions might arise from variation in species phenotypes occurring over smaller spatial scales (Des Roches et al. 2018). Notably, within-region spatial structuring was never significant in analyses focusing on each functional indicator separately (VP2), which were instead generally characterised by a very large joint variation between community and environment. This suggests that species-sorting along environmental gradients is a more important driver of individual ecosystem processes (e.g. litter decomposition, biomass accrual of individual organism groups), dependent on a narrower range of organisms and specific nutrients.

All ecosystem processes are not structured by space, environment and community in the same way

Interestingly, in our analyses that partitioned variation in each of our functional indicators separately, we were only able to explain variation in leaf decomposition (58–63% of total variation explained), and the biomass accrual of algae and fungi (up to 83% of variation explained). These represent true ecosystem-level processes regulated by several organisms groups that largely operate at the same local scales over which we quantified community composition and most of our environmental variables. Despite the differences in our capacity to explain variation in all of our indicators separately, inclusion of all functional indicators in the combined ecosystem functioning matrix increased the total variation explained, and was necessary for detecting spatial structuring in functioning at the within-region scale, suggesting that all indicators together better characterised the ecosystem functioning and spatial connectivity of the whole ecosystem.

Influence of taxonomic groups and species traits on global ecosystem functioning

We observed differences in the importance of different components of the biota in our analyses fitting each of the taxonomic groups separately. Macrophyte community composition had the largest unique effect (12%) on overall ecosystem functioning, which might reflect knock-on effects of the multiple influences of macrophyte beds on local environments (e.g. reductions in flow and light, changed nutrient status, and increased habitat surface area (van Donk et al. 1993; Jeppesen et al. 1998)), on other co-occurring taxonomic groups (Johnson and Hering 2010) and ultimately on ecosystem functioning. Diatoms, invertebrates and fish (7%) also had significant unique effects on functioning, which might reflect direct bottom-up (e.g. algae as resource subsidy for leaf-consuming detritivores) or top-down (e.g. trait-mediated effects of fish on consumer behaviour) control on processes within the food web (Raffaelli et al. 2002; Gessner et al. 2010; Kéfi et al. 2012).

Against our expectations, the total variation explained in our analyses did not increase when species were characterised by their traits rather than taxonomic identities for both invertebrates and fish, contradicting the idea that species traits rather than taxonomic identities better capture the key attributes of biota regulating ecosystem functioning (Lavorel and Garnier 2002; Enquist et al. 2015). However, most species trait databases, including those used here, suffer from two main shortcomings when used to predict ecosystem functioning. Firstly, trait allocations based on these databases may have limited capacity to capture the breadth of spatial–temporal variability in species phenotypes (i.e. intraspecific variation). For example, although our organism groups were all sampled at the same time of year, species were not necessarily at an identical developmental stage in all regions, as suggested by differences in biomass of some of our detritivore taxa (Appendix S2, Table S2.2). Such systematic differences in the body size of key consumers among regions are likely to be further associated with differences in their feeding behaviours (Layer et al. 2013; Frainer and McKie 2015). Secondly, information on true functional effect traits (e.g. resource acquisition rates) is often limited in large-scale databases (Truchy et al. 2015), which are instead biased towards traits regulating species responses to environmental variation (e.g., environmental tolerances) that are likely to predict functioning only indirectly. Nevertheless, the use of traits did have value in our analyses by reducing complexity in the data set, whereby information on many species is reduced to information on a lower number of traits, which might explain why the role of spatial structuring was more discriminated in our analyses of all ecosystem processes combined.

Conclusion

Field studies are often able to explain a substantial portion of variation in ecosystem functioning based on information on abiotic and biotic parameters, quantified at local scales, alone (Dangles et al. 2004; Young and Collier 2009; Frainer et al. 2014; Frainer and McKie 2015). However the proportion of unexplained variation is often very high, especially at larger (e.g. whole catchment, regional or continental) scales (McKie and Malmqvist 2009; Woodward et al. 2012; Dirzo et al. 2014). Significantly, these are the scales where many vital ecosystem services arise (e.g. water purification and nutrient cycling services), derived from multiple ecosystem processes and organism groups that link across habitat boundaries within larger scale spatial networks (Truchy et al. 2015; Brose and Hillebrand 2016). Overall, our results reveal the extent to which this variation might be attributed to spatial structuring, and highlight the need for more research on the mechanisms underpinning such structuring to support improved management of ecosystem functioning and services. Indeed, the approaches needed to improve delivery of a set of ecosystem functions and services are likely to differ substantially according to how they are structured spatially. This might range from a focus on improving local-scale environmental conditions when species sorting is the dominant mechanism regulating variation in functioning, to a focus on improving conditions for the particular key stone or foundational species that drive significant organisation in ecosystem functioning (Pringle et al. 2010). However, in many cases it is likely that key linkages in flows of organisms and materials among habitat patches and between ecosystem types will be needed to achieve the greatest improvements in ecosystem functioning and service delivery.

References

Ahti T, Hämet-Ahti L, Jalas J (1968) Vegetation zones and their sections in northwestern Europe. Ann Bot Fenn 5(3):169–211

Ashton KG, Tracy MC, de Queiroz A (2000) Is Bergmann’s rule valid for mammals? Am Nat 156(4):390–415

Benfield EF (1996) Leaf breakdown in stream ecosystems. In: Hauer FR, Lamberti GA (eds) Methods in stream ecology. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 579–589

Blanchet FG, Legendre P, Borcard D (2008) Forward selection of explanatory variables. Ecology 89(9):2623–2632

Borcard D, Legendre P (2002) All-scale spatial analysis of ecological data by means of principal coordinates of neighbour matrices. Ecol Model 153(1):51–68

Boyero L, Graca MAS, Tonin AM et al (2017) Riparian plant litter quality increases with latitude. Sci Rep 7(1):10562

Brose U, Hillebrand H (2016) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in dynamic landscapes. Philos Trans R Soc B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0267

Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Allen AP, Savage VM, West GB (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85(7):1771–1789

Burdon FJ, Harding JS (2008) The linkage between riparian predators and aquatic insects across a stream-resource spectrum. Freshw Biol 53(2):330–346

Carlson PE, McKie BG, Sandin L, Johnson RK (2016) Strong land-use effects on the dispersal patterns of adult stream insects: implications for transfers of aquatic subsidies to terrestrial consumers. Freshw Biol 61(6):848–861

Cornacchia L, van de Koppel J, van der Wal D, Wharton G, Puijalon S, Bouma TJ (2018) Landscapes of facilitation: how self-organized patchiness of aquatic macrophytes promotes diversity in streams. Ecology 99(4):832–847

Cottenie K (2005) Integrating environmental and spatial processes in ecological community dynamics. Ecol Lett 8(11):1175–1182

Dangles O, Gessner MO, Guerold F, Chauvet E (2004) Impacts of stream acidification on litter breakdown: implications for assessing ecosystem functioning. J Appl Ecol 41:365–378

Declerck SAJ, Coronel JS, Legendre P, Brendonck L (2011) Scale dependency of processes structuring metacommunities of cladocerans in temporary pools of High-Andes wetlands. Ecography 34(2):296–305

Des Roches S, Post DM, Turley NE et al (2018) The ecological importance of intraspecific variation. Nat Ecol Evol 2(1):57–64

Dietrich AL, Nilsson C, Jansson R (2013) Phytometers are underutilised for evaluating ecological restoration. Basic Appl Ecol 14(5):369–377

Dirzo R, Young HS, Galetti M, Ceballos G, Isaac NJ, Collen B (2014) Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345(6195):401–406

Dong X, Fisher SG (2019) Ecosystem spatial self-organization: free order for nothing? Ecol Complex 38:24–30

Dray S, Dufour AB (2007) The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw 22(4):1–20

Dray S, Legendre P, Blanchet FG (2013) packfor: forward Selection with permutation (Canoco p.46). R package version 0.0-8/r109

Dray S, Legendre P, Peres-Neto PR (2006) Spatial modelling: a comprehensive framework for principal coordinate analysis of neighbour matrices (PCNM). Ecol Model 196(3–4):483–493

Enquist BJ, Norberg J, Bonser SP et al (2015) Scaling from traits to ecosystems: developing a general trait driver theory via integrating trait-based and metabolic scaling theories. In: Pawar S, Woodward G, Dell AI (eds) Trait-based ecology—from structure to function. Advances in ecological research. Academic Press, London, pp 249–318

Frainer A, McKie BG (2015) Shifts in the diversity and composition of consumer traits constrain the effects of land use on stream ecosystem functioning. In: Pawar S, Woodward G, Dell AI (eds) Trait-based ecology—from structure to function. Advances in ecological research. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 169–200

Frainer A, McKie BG, Malmqvist B, Woodward G (2014) When does diversity matter? Species functional diversity and ecosystem functioning across habitats and seasons in a field experiment. J Anim Ecol 83(2):460–469

Frainer A, Polvi LE, Jansson R, McKie BG (2017) Enhanced ecosystem functioning following stream restoration: the roles of habitat heterogeneity and invertebrate species traits. J Appl Ecol 55:377–385

Gagic V, Bartomeus I, Jonsson T et al (2015) Functional identity and diversity of animals predict ecosystem functioning better than species-based indices. Proc Biol Sci 282(1801):20142620

Gessner MO (2005) Ergosterol as a measure of fungal biomass. In: Graça MAS, Bärlocher F, Gessner MO (eds) Methods to study litter decomposition: a practical guide. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 189–195

Gessner MO, Chauvet E (2002) A case for using litter breakdown to assess functional stream integrity. Ecol Appl 12(2):498–510

Gessner MO, Swan CM, Dang CK et al (2010) Diversity meets decomposition. Trends Ecol Evol 25(6):372–380

Göthe E, Angeler DG, Gottschalk S, Löfgren S, Sandin L (2013) The influence of environmental, biotic and spatial factors on diatom metacommunity: structure in Swedish headwater streams. PLoS ONE 8(8):e72237

Grime JP (1998) Benefits of plant diversity to ecosystems: immediate, filter and founder effects. J Ecol 86 (6):902-910

Grönroos M, Heino J, Siqueira T, Landeiro VL, Kotanen J, Bini LM (2013) Metacommunity structuring in stream networks: roles of dispersal mode, distance type, and regional environmental context. Ecol Evol 3(13):4473–4487

Heffernan JB, Soranno PA, Angilletta MJ et al (2014) Macrosystems ecology: understanding ecological patterns and processes at continental scales. Front Ecol Environ 12(1):5–14

Heino J, Melo AS, Bini LM et al (2015) A comparative analysis reveals weak relationships between ecological factors and beta diversity of stream insect metacommunities at two spatial levels. Ecol Evol 5(6):1235–1248

Hildrew AG, Raffaelli DG, Edmonds-Brown R (2007) Body size: the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hillebrand H (2004) On the generality of the latitudinal diversity gradient. Am Nat 163(2):192–211

Hooper DU, Solan M, Symstad AJ et al (2002) Species diversity, functional diversity, and ecosystem functioning. In: Al Loreau M (ed) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, synthesis and perspectives. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 195–281

Jeppesen E, Sondergaard M, Sondergaard M, Christoffersen K (1998) The structuring role of submerged macrophytes in lakes. Springer, New York

Johnson RK, Goedkoop W, Sandin L (2004) Spatial scale and ecological relationships between the macroinvertebrate communities of stony habitats of streams and lakes. Freshw Biol 49(9):1179–1194

Johnson RK, Hering D (2010) Spatial congruency of benthic diatom, invertebrate, macrophyte, and fish assemblages in European streams. Ecol Appl 20(4):978–992

Jonsson M (2006) Species richness effects on ecosystem functioning increase with time in an ephemeral resource system. Acta Oecol 29(1):72–77

Kéfi S, Berlow EL, Wieters EA et al (2012) More than a meal… integrating non-feeding interactions into food webs. Ecol Lett 15(4):291–300

Lamberti GA, Resh VH (1983) Stream periphyton and insect herbivores: an experimental study of grazing by a caddisfly population. Ecology 64(5):1124–1135

Lavorel S, Garnier E (2002) Predicting changes in community composition and ecosystem functioning from plant traits: revisiting the Holy Grail. Funct Ecol 16:545–556

Lavorel S, Grigulis K, McIntyre S et al (2008) Assessing functional diversity in the field—methodology matters! Funct Ecol 22(1):134–147

Layer K, Hildrew AG, Woodward G (2013) Grazing and detritivory in 20 stream food webs across a broad pH gradient. Oecologia 171(2):459–471

Lecerf A, Chauvet E (2008) Intraspecific variability in leaf traits strongly affects alder leaf decomposition in a stream. Basic Appl Ecol 9(5):598–605

Legendre P, Gallagher ED (2001) Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129(2):271–280

Legendre P, Legendre L (2012) Multiscale analysis: spatial eigenfunctions. In: Legendre P, Legendre L (eds) Developments in environmental modelling. Elsevier, Oxford, pp 859–906

Leibold MA, Holyoak M, Mouquet N et al (2004) The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol Lett 7(7):601–613

Logue JB, Mouquet N, Peter H, Hillebrand H (2011) Empirical approaches to metacommunities: a review and comparison with theory. Trends Ecol Evol 26(9):482–491

Loreau M, Mouquet N, Holt RD (2005) From metacommunities to metaecosystems. In: Driscoll DA (ed) Metacommunities: spatial dynamics and ecological communities. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 418–438

McKie BG, Cranston PS (2005) Size matters: systematic and ecological implications of allometry in the responses of chironomid midge morphological ratios to experimental temperature manipulations. Can J Zool 83(4):553–568

McKie BG, Malmqvist B (2009) Assessing ecosystem functioning in streams affected by forest management: increased leaf decomposition occurs without changes to the composition of benthic assemblages. Freshw Biol 54(10):2086–2100

McKie BG, Petrin Z, Malmqvist B (2006) Mitigation or disturbance? Effects of liming on macroinvertebrate assemblage structure and leaf-litter decomposition in the humic streams of northern Sweden. J Appl Ecol 43(4):780–791

McKie BG, Schindler M, Gessner MO, Malmqvist B (2009) Placing biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in context: environmental perturbations and the effects of species richness in a stream field experiment. Oecologia 160(4):757–770

McKie BG, Woodward G, Hladyz S et al (2008) Ecosystem functioning in stream assemblages from different regions: contrasting responses to variation in detritivore richness, evenness and density. J Anim Ecol 77(3):495–504

Meyer E (1989) The relationship between body length parameters and dry mass in running water invertebrates. Arch Hydrobiol 117(2):191–203

Naeem S, Wright JP (2003) Disentangling biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning: deriving solutions to a seemingly insurmountable problem. Ecol Lett 6:567–579

Naturvårdsverket (2003) Handledning för miljöövervakning - Undersökningstyp: Makrofyter i vattendrag. Version 1:2, 2003-12-04

Naturvårdsverket (2010) Handledning för miljöövervakning - Undersökningstyp: Bottenfauna i sjöars litoral och vattendrag - tidsserier. Version 1:1, 2010-03-01

O’Connor NE, Donohue I (2013) Environmental context determines multi-trophic effects of consumer species loss. Glob Change Biol 19(2):431–440

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Roeland Kindt R et al (2015) vegan: community ecology package. Package version 2.3-1

Perkins DM, Mckie BG, Malmqvist B, Gilmour SG, Reiss J, Woodward G (2010) Environmental warming and biodiversity-ecosystem functioning in freshwater microcosms: partitioning the effects of species identity, richness and metabolism. Adv Ecol Res 43:177–209

Pinel-Alloul B, Niyonsenga T, Legendre P (1995) Spatial and environmental components of freshwater zooplankton structure. Écoscience 2(1):1–19

Pringle RM, Doak DF, Brody AK, Jocqué R, Palmer TM (2010) Spatial pattern enhances ecosystem functioning in an African savanna. PLoS Biol 8(5):e1000377

Raab B, Vedin H (1995) Sveriges Nationalatlas: klimat, sjöar och vattendrag. Bra böcker, Höganäs

Raffaelli D, van der Putten WH, Persson L et al (2002) Multi-trophic dynamics and ecosystem processes. In: Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P (eds) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, synthesis and perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 147–154

R Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Reice SR (1994) Nonequilibrium determinants of biological community structure. Am Sci 82(5):424–435

Schmidt-Kloiber A, Hering D (2015) www.freshwaterecology.info—an online tool that unifies, standardises and codifies more than 20,000 European freshwater organisms and their ecological preferences. Ecol Indic 53:271–282

Schmitz OJ (2010) Spatial dynamics and ecosystem functioning. PLoS Biol 8(5):e1000378

Sponseller RA, Temnerud J, Bishop K, Laudon H (2014) Patterns and drivers of riverine nitrogen (N) across alpine, subarctic, and boreal Sweden. Biogeochemistry 120(1):105–120

Srivastava DS, Vellend M (2005) Biodiversity-ecosystem function research: is it relevant to conservation? Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36:267–294

Tachet H, Bournaud M, Richoux P, Usseglio-Polatera P (2010) Invertébrés d’eau douce - systématique, biologie, écologie. CNRS Editions, Paris

Törnroos A, Nordström MC, Aarnio K, Bonsdorff E (2015) Environmental context and trophic trait plasticity in a key species, the tellinid clam Macoma balthica L. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 472:32–40

Truchy A, Angeler DG, Sponseller RA, Johnson RK, McKie BG (2015) Chapter two—linking biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and services, and ecological resilience: towards an integrative framework for improved management. In: Guy W, David AB (eds) Advances in ecological research. Academic Press, London, pp 55–96

van Donk E, Gulati RD, Iedema A, Meulemans JT (1993) Macrophyte-related shifts in the nitrogen and phosphorus contents of the different trophic levels in a biomanipulated shallow lake. Hydrobiologia 251(1):19–26

Venail PA, Maclean RC, Meynard CN, Mouquet N (2010) Dispersal scales up the biodiversity–productivity relationship in an experimental source-sink metacommunity. Proc R Soc Lond B 277(1692):2339–2345

Violle C, Navas M-L, Vile D et al (2007) Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos 116(5):882–892

Von Schiller D, MartÍ E, Riera JL, Ribot M, Marks JC, Sabater F (2008) Influence of land use on stream ecosystem function in a Mediterranean catchment. Freshw Biol 53(12):2600–2612

Widenfalk LA, Leinaas HP, Bengtsson J, Birkemoe T (2018) Age and level of self-organization affect the small-scale distribution of springtails (Collembola). Ecosphere 9(1):e02058

Woodward G, Gessner MO, Giller PS et al (2012) Continental-scale effects of nutrient pollution on stream ecosystem functioning. Science 336(6087):1438–1440

Young RG, Collier KJ (2009) Contrasting responses to catchment modification among a range of functional and structural indicators of river ecosystem health. Freshw Biol 54(10):2155–2170

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. This work was supported by the project WATERS (to R.K.J. and B.G.M.), funded by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Dnr 10/179) and the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management. We thank the following collaborators for field and lab work: Jenni Tuokko, Tobias Nilsson, Elodie Chapurlat, Didier Baho, Elin Lavonen, Mikael Östlund, Magda-Lena Wiklund McKie and Maisam Ali. Comments by referees were very much appreciated and improved the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Truchy, A., Göthe, E., Angeler, D.G. et al. Partitioning spatial, environmental, and community drivers of ecosystem functioning. Landscape Ecol 34, 2371–2384 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00894-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00894-9