Abstract

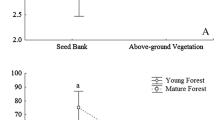

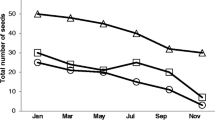

Past land use is an important factor determining vegetation in temperate deciduous forests. Little is known about the long-term persistence of these impacts on vegetation but especially on the seed bank. This study assessed whether soil characteristics remain altered 1,600 years after human occupation and if this yielded persistent differences in forest plant communities and their seed bank in particular. Compiègne forest is located in northern-France and has a history of continuous forest cover since the end of Roman times. Twenty-four Gallo-Roman and 24 unoccupied sites were sampled and data were analysed using paired sample tests to investigate whether soil, vegetation and seed bank still differed significantly. The soil was persistently altered on the Gallo-Roman sites resulting in elevated phosphorus levels and pH (dependent on initial soil conditions) which translated into increased vegetation and seed bank species richness. Though spatially isolated, Gallo-Roman sites supported both a homogenized vegetation and seed bank. Vegetation differences were not the only driver behind seed bank differences. Similarity between vegetation and seed bank was low and the possibility existed that agricultural ruderals were introduced via the former land use. Ancient human occupation leaves a persistent trace on forest soil, vegetation and seed bank and appears to do so at least 1,600 years after the former occupation. The geochemical alterations created an entirely different habitat causing not only vegetation but also the seed bank to have altered and homogenized composition and characteristics. Seed bank differences likely persisted by the traditional forest management and altered forest environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anne P (1945) Sur le dosage rapide du carbone organique de sols. Annales Agronomiques 15:161–172 (in French)

Aubert G (1978) Méthodes d’ analyse des sols. Edition C.R.D.P., Marseille (in French)

Bellemare J, Motzkin G, Foster DR (2002) Legacies of the agricultural past in the forested present: an assessment of historical land use effects on rich mesic forests. J Biogeogr 29:1401–1420

Bigwood DW, Inouye DW (1988) Spatial pattern analysis of seed banks: an improved method and optimized sampling. Ecology 69:497–507

Bossuyt B, Hermy M (2000) Restoration of the understorey layer of recent forest bordering ancient forest. Appl Veg Sci 3:43–50

Bossuyt B, Hermy M (2001) Influence of land use history on seed banks in European temperate forest ecosystems: a review. Ecography 24:225–238

Bossuyt B, Hermy M, Deckers J (1999) Migration of herbaceous plant species across ancient-recent forest ecotones in central Belgium. J Ecol 87:628–638

Bossuyt B, Heyn M, Hermy M (2002) Seed bank and vegetation composition of forest stands of varying age in central Belgium: consequences for regeneration of ancient forest vegetation. Plant Ecol 162:33–48

Bray RH, Kurtz LT (1945) Determination of total, organic and available forms of phosphorus in soils. Soil Sci 59:39–45

Briggs JM, Spielmann KA, Schaafsma H et al (2006) Why ecology needs archaeologists and archaeology needs ecologists. Front Ecol Environ 4(4):180–188

Bürgi M, Gimmi U (2007) Three objectives of historical ecology: the case of litter collecting in Central Europena forests. Landsc Ecol 22:77–87

Cain ML, Damman H, Muir A (1998) Seed dispersal and the Holocene migration of woodland herbs. Ecol Monogr 68:325–347

Compton JE, Boone RD (2000) Long-term impacts of agriculture on soil carbon and nitrogen in New England forests. Ecology 81:2314–2330

Dambrine E, Dupouey J-L, Laüt L et al (2007) Present forest biodiversity patterns in France related to former Roman agriculture. Ecology 88:1430–1439

Decocq G, Vieille V, Racinet P (2002) Influence des facteurs historiques sur la végétation actuelle: le cas des mottes castrales en milieu forestier (Picardie, France). Acta Bot Gall 149:197–215 (in French)

Doyen B, Thuillier P, Decocq G (2004) Archéologie des milieux boisés en Picardie. Revue Archéologique de Picardie 1/2:149–164 (in French)

Dupouey J-L, Dambrine E, Lafitte JD et al (2002) Irreversible impact of past land use on forest soils and biodiversity. Ecology 83:2978–2984

Ellenberg H (1996) Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen in ökologischer, dynamischer und historischer Sicht. Ulmer, Stuttgart (in German)

Ellenberg H, Weber HE, Ruprcht D et al (1992) Zeigerwerte von pflanzen in Mitteleuropa. Scr Geobot 18:1–258 (in German)

Flinn KM, Vellend M (2005) Recovery of forest plant communities in post-agricultural landscapes. Front Ecol Environ 3:243–250

Flinn KM, Vellend M, Marks PL (2005) Environmental causes and consequences of forest clearance and agricultural abandonment in central New York, USA. J Biogeogr 32:439–452

Fraterrigo JM, Turner MG, Pearson SM (2006) Interactions between past land use, life-history traits and understory spatial heterogeneity. Landsc Ecol 21:777–790

Graae BJ, Sunde PB, Fritzborger B (2003) Vegetation and soil differences in ancient opposed to new forests. For Ecol Manage 117:179–190

Harrelson SM, Matlack GR (2006) Influence of stand age and physical environment on the herb composition of second-growth forest, Strouds Run, Ohio, USA. J Biogeogr 33:1139–1149

Hermy M, Honnay O, Firbank L et al (1999) An ecological comparison between ancient and other forest plant species of Europe, and the implications for forest conservation. Biol Conserv 91:9–22

Honnay O, Hermy M, Coppin P (1999) Impact of habitat quality on forest plant species colonization. For Ecol Manage 115:157–170

Hunt R, Hogdson JH, Thompson K et al (2004) A new practical tool for deriving a functional signature for herbaceous vegetation. Appl Veg Sci 7:163–170

Kent M, Coker P (1992) Vegetation description and analysis. A practical approach. Wiley, Chichester

Koerner W, Dupouey J-L, Dambrine E et al (1997) Influence of past land-use on the vegetation and soils of present day forest in the Vosges mountains, France. J Ecol 85:351–358

Lambinon J, De Langhe J-E, Delvosalle L et al (1998) Flora van België, het Groothertogdom Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk en de aangrenzende gebieden (Pteridofyten en Spermatofyten). Nationale plantentuin van België, Meise (in Dutch)

Lanier L, Badré M, Delabraze P et al (1986) Précis de sylviculture. ENGREF, Nancy (in French)

Leonardi G, Miglavacca M, Nardi S (1999) Soil phosphorus analysis as an integrative tool for recognizing buried ancient ploughsoils. J Archaeol Sci 26:343–352

Loeppert RH, Suarez DL (1996) Carbonate and gypsum. In: Bigham JM, Bartels JM (eds) Methods of soil analysis, third part, chemical methods. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, pp 437–474

McLauchlan K (2006) The nature and longevity of agricultural impacts on soil carbon and nutrients: a review. Ecosystems 9:1364–1382

Maussion A (2003) Occupation ancienne du sol et milieux forestiers actuels, en France métropolitaine. Synthèse bibliographique. INRA-Nancy, Champenoux (in French)

O.N.F. (1995) Foret domaniale de Compiegne – Révision d’ amenagement 1996–2010. Office National des Forets – Direction Nationale de Picardie – Division de Compiegne, Compiègne (in French)

Pansu M, Gautheyrou J (2003) L’analyse du Sol Minéralogique, Organique et Minérale. Springer-Verlag, Paris (in French)

Peterken GF (1996) Natural woodland: ecology and conservation in Northern temperate regions. Cambridge University Press Inc., United Kingdom

Peterken GF, Game M (1984) Historical factors affecting the number and distribution of vascular plant species in the woodlands of central Lincolnshire. J Ecol 72:155–182

Pounds NJG (1973) An historical geography of Europe 450 B.C.–A.D. 1330. Cambridge University press Inc., United Kingdom

Rameau JC, Mansion D, Dumé G et al (1989) Flore Forestière Française, Guide Ecologique Illustré. 1. Plaines et Collines. Institut pour le développement forestier, Paris (in French)

Raup DM, Crick RE (1979) Measurement of faunal diversity in paleontology. J Paleontol 53:1213–1227

Runkle JR (1985) The disturbance regime in temperate forests. In: Pickett STA, White PS (eds) The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics. Academic Press, London, pp 17–33

Richards PW, Clapham AR (1941) Juncus effusus L J Ecol 29:375–380

Sandor JA, Gersper PL, Hawley JW (1990) Prehistoric agricultural Terraces and soils in the Mimbres area, New Mexico. World Arch 22(1):70–86

Sandor JA, Eash NS (1995) Ancient agricultural soils in the Andes of Southern Peru. Soil Sci Soc Am J 59:170–179

Schulte LA, Mladenoff DJ, Crow TR et al (2007) Homogenization of Northern U.S. Great lakes forest due to human land use. Landsc Ecol 22:1089–1103

Siegel S, Castellan NJJ (1988) Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill book company, Singapore

SPSS (2003) SPSS Inc., Chicago

Ter Heerdt GNJ, Verweij GL, Bekker RM et al (1996) An improved method for seed-bank analysis: seedling emergence after removing the soil by sieving. Funct Ecol 10:144–151

Thompson K, Grime JP (1979) Seasonal variation in the seed banks of herbaceous species in ten contrasting habitats. J Ecol 67:893–921

Thompson K, Bakker JP, Bekker RM et al (1998) Ecological correlates of seed persistence in soil in the North-West European flora. J Ecol 86:163–169

Thuillier P (2004) La prospection en milieu boisé. In: Schwerdroffer J, Racinet P (eds) Méthodes et initiations d’histoire et d’archéologie. Editions du Temps, Nantes, pp 26–37 (in French)

Tombal P (1972) Etude phytocoenologique et esquisse macrobiocoenotique du proclimax forestier (Ilici-Fagetum) des Beaux-Monts de Compiègne (Oise-France). Bulletin de la société botanique du nord de la France 25:19–52 (in French)

Van der Maarel E (1979) Transformation of cover-abundance values in phytosociology and its effects on community similarity. Vegetatio 39:97–114

Vanwalleghem T, Verheyen K, Hermy M et al (2004) Legacies of Roman land-use in the present-day vegetation in Meerdaal Forest (Belgium)? Belg J Bot 137:181–187

Vellend M, Verheyen K, Flinn KM et al (2007) Homogenization of forest plant communities and weakening of species-environment relationships via agricultural land use. J Ecol 95:565–573

Verheyen K, Hermy M (2001) The relative importance of dispersal limitation of vascular plants in secondary forest succession in Muizen forest, Belgium. J Ecol 89:829–840

Verheyen K, Bossuyt B, Hermy M et al (1999) The land use history (1278–1990) of a mixed hardwood forest in western Belgium and its relationship with chemical soil characteristics. J Biogeogr 26:1115–1128

Watkinson AR, Riding AE, Cowie NR (2001) A community and population perspective of the possible role of grazing in determining the ground flora of ancient woodlands. Forestry 74:231–239

Willis KJ, Birks HJB (2006) What is natural? The need for a long-term perspective in biodiversity conservation. Science 314:1261–1265

Wood T, Bormann FH, Voigt GK (1984) Phosphorus cycling in a Northern Hardwood Forest: biological and chemical control. Science 223:391–393

Acknowledgements

J.P. would like to thank Eric van Beek for the help provided with the seed bank experiment. The authors thank Stéphanie Renaux for her contribution to field work and preliminary data analysis and the French ‘Office National des Forêts’ for having facilitated our field work and provided useful information about abiotic conditions and management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

Vegetation

Agrostis canina L.: 1, 0; Agrostis stolonifera L.: 0, 1; Allium ursinum L.: 1, 0; Calamagrostis epigejos (L.) Roth: 3, 1; Campanula trachelium L.: 2, 0; Carex elata All.: 1, 0; Cardamine flexuosa With: 1, 0: Cardamine pratensis L.: 1, 1; Carex depauperata Curt. Ex With.: 1, 0; Carex flacca Schreb.: 1, 1; Carex strigosa Huds.: 0, 2; Cephalantera damasonium (Mill.) Druce: 3, 0; Chaerophyllum temulum L.: 1, 0; Chelidonium majus L.: 2, 0; Chrysosplenium oppostifolium L.: 1, 0; Cornus mas L.: 0, 1; Crataegus laevigata (Poiret) DC.: 0, 2; Dactylis glomerata L.: 1, 0; Deschampsia flexuosa (L.) Trin.: 0, 3; Dryopteris dilatata (Hoffman) A. Gray: 1, 1; Elymus caninus (L.) L.: 1, 1; Epilobium montanum L.: 2, 0; Epilobium hirsutum L.: 2, 1; Epilobium roseum Schreb.: 1, 0; Equisetum sp.: 1, 0; Festuca sp.: 0, 1; Fragaria vesca L.: 2, 1; Heracleum sphondylium L.: 1, 0; Holcus lanatus L.: 0, 1; Hypericum tetrapterum Fries: 1, 0; Ilex aquifolium L.: 0, 4; Impatiens noli-tangere L.: 1, 0; Iris pseudacorus L.: 1, 0; Luzula forsteri Smith DC.: 0, 2; Maianthemum bifolium (L.) F.W. Schmidt: 1, 0; Melampyrum pratense L.: 1, 2; Molinea caerula (L.) Moench: 0, 2; Polystichum setiferum (Frossk.) Woynar: 1, 1; Primula elatior (L.) Hill: 4, 0; Prunus spinosa L.: 1, 0; Ranunculus auricomus L.: 2, 2; Ranunculus repens L.: 1, 0; Ribes uva-crispa L.: 2, 1; Ribes rubrum L.: 1, 0; Rubus idaeus L.: 1, 1; Rumex sanguineus L.: 1, 0; Rumex obtusifolius L.: 4, 0; Ruscus aculeatus L.: 1, 2; Teucrium scorodonia L.: 1, 2; Torilis japonica (Houtt.) DC.: 1, 0; Veronica sp.: 1, 0; Veronica chamaedrys L.: 1, 0; Viburnum opulus L.; 3, 0; Vincetoxicum hirundaria Med.: 2, 0; Viola odorata L.: 1, 0; Viola riviniana Reichenb.: 1, 2

Seed bank

Agrostis capillaris L.: 0, 1; Agrostis stolonifera L.: 0, 1; Ajuga reptans L.: 0, 1; Atropa bella-donna L.: 4, 0; Brachypodium sylvaticum (Huds.) Beauv.: 1, 0; Cardamine impatiens L.: 3, 0; Cardamine sp.: 4, 0; Carex pendula Huds.: 1, 0; Carex pilulifera L.: 1, 2; Carex remota Jusl. Ex L.: 1, 1; Chaerophyllum temulum L.: 2, 0; Chenopodium album L.: 1, 0; Chenopodium polyspermum L.: 2, 0; Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronq.: 3,1; Cytisus scoparius (L.) Link.: 1, 3; Deschampsia cespitosa (L.) Beauv.: 0, 1; Epilobium ciliatum Rafin.: 3, 0; Epilobium lanceolatum Seb. Et Mauri: 3, 1; Euphorbia amygdaloides L. 1, 0; Festuca gigantea (L.) Vill.: 1, 0; Geum urbanum L.: 1, 0; Hypericum dubium Leers: 0, 1; Hypericum humifusum L.: 1, 1; Hypericum pulchrum L.: 0, 1; Hypericum tetrapterum Fries: 0, 1; Juncus articulatus L.: 1, 2; Juncus bulbosus L.: 1, 0; Lapsana communis L.: 1, 0; Milium effusum L.: 2, 0; Plantago major L.: 1, 0; Poa nemoralis L.: 0, 1; Poa pratensis L.: 1, 1; Poa trivialis L.: 4, 0; Polygonum persicaria L.: 1, 0; Potentilla reptans L.: 0, 1; Potentilla sterilis (L.) Garcke: 1, 2; Ranunculus repens L.: 1, 0; Rumex obtusifolius L.: 1, 0; Sagina procumbens L.: 1, 1; Senecio jacobea L.: 1, 0; Solanum nigrum L.: 1, 1; Sonchus arvensis L.: 1, 0; Sonchus asper (L.) Hill: 0, 1; Stachys sylvatica L.: 1, 1; Teucrium scorodonia L.: 1, 0; Veronica montana L.: 1, 0

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plue, J., Hermy, M., Verheyen, K. et al. Persistent changes in forest vegetation and seed bank 1,600 years after human occupation. Landscape Ecol 23, 673–688 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-008-9229-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-008-9229-4