Abstract

While patterns of adolescent personality development are country-specific, previous studies that have examined them have been limited to the Netherlands and Finland. This study aimed to identify the patterns of personality development and examine the relationship between these patterns and psychosocial functioning among Japanese adolescents. Overall, 618 Japanese adolescents (49.5% girls; 16 years) participated in the annual longitudinal survey from 2013 to 2016. Using latent class growth analysis, the following four patterns of personality development were identified: resilient, over-controlled, vulnerable, and moderate. Although the mean-level changes in the Big Five domains were generally insignificant among the four patterns, the vulnerable pattern showed a progressive increase in conscientiousness, and the moderate pattern showed a decrease in neuroticism and an increase in conscientiousness. Furthermore, multivariate analysis of variance tests indicated that the resilient pattern showed higher subjective well-being and lower psychosocial problems than the other personality patterns; the over-controlled pattern showed higher internalizing problems than the resilient pattern; the vulnerable pattern showed lower subjective well-being and higher internalizing problems than the other patterns; and the moderate pattern scored between the resilient, over-controlled, and vulnerable patterns in both subjective well-being and psychosocial problems. These findings suggest that the vulnerable and moderate patterns, which are immature patterns compared to the resilient and over-controlled ones, showed positive changes to the direction of maturity from middle to late adolescence in Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of psychosocial challenges characterized by physical changes, the development of abstract reasoning, and renegotiation of the parent-child relationship (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). During this period, adolescents experience various psychosocial functions, such as life satisfaction, happiness, depressive mood, and anxiety (Schwartz & Petrova, 2018). Personality traits, which are well described by the Big Five model (Goldberg, 1993), have been strongly associated with these psychosocial functions. The Big Five model measures personality using five broad domains: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Research has shown that higher neuroticism is strongly associated with psychosocial maladjustment, while higher extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness are strongly associated with higher subjective well-being (Bleidorn et al., 2020). Although human personality factors can be determined with these specific differentiated traits that are uniquely associated with psychosocial functioning, personality can also be understood with a combination of these traits. This person-centered approach has identified several personality types based on a composition of personality traits (Asendorpf et al., 2001). Longitudinal studies have provided insights into whether personality types are maintained during adolescence or whether they change as adolescents move toward adulthood (Hill & Edmonds, 2017). Therefore, focusing on the patterns in personality development using longitudinal surveys can help in predicting the patterns that are psychosocially healthy or unhealthy for adolescents (Van den Akker et al., 2013). While personality type and patterns tend to be country-specific, longitudinal studies have been limited to the Netherlands (Branje et al., 2010) and Finland (de Haan et al., 2013). To clarify personality development in adolescence, further evidence from different countries is needed. To fill this research gap, the present study aimed to identify the patterns of personality development among Japanese adolescents and examine their longitudinal relations to psychosocial functioning.

Typological Approach to Personality Traits in Adolescence

As a classical approach, personality types were identified using the Q-sorting procedure (Block, 1971). This method focuses on an individuals’ ability to control the environment (i.e., ego-control) and respond flexibly to its demands (i.e., ego-resilience), and proposes the following three personality types: resilients, or individuals who control their ego and adapt flexibly to their environment (high ego-control, high ego-resiliency); under-controllers, or individuals with weak ego control and an inability to adapt to the demands of the environment (low ego-control, high ego-resiliency); and over-controllers, or individuals whose ego-control is too strong and who overreact to the demands of the environment (high ego-control, low ego-resiliency) (Block & Block, 1980). These three personality types have also been noted in research using the Big Five model (Asendorpf et al., 2001). To obtain the three robust personality types, previous studies conducted a two-step clustering procedure, in which Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis is followed by nonhierarchical k-means cluster analysis (Alessandri et al., 2014) or latent class (profile) analysis (Ferguson & Hull, 2018). According to a series of previous studies, the resilient type is characterized by low neuroticism, high extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness; the under-controlled type exhibits high extroversion and openness; and the over-controlled type exhibits high agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Although the resilient, under-controlled, and over-controlled types have been repeatedly observed cross-culturally in many previous studies (Alessandri et al., 2014), other personality types with different characteristics have also been found. For example, studies using latent class analysis have identified four personality types in Finnish (Leikas & Salmela-Aro, 2014), Italian (Favini et al., 2018), and Chinese adolescent samples (Xie et al., 2016). Three profiles among the four personality types are consistent throughout previous studies: resilient (low in neuroticism and high in extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), moderate (average in all Big Five traits), and vulnerable (high in neuroticism and low in extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness). Regarding the remaining personality types, the under-controlled type (high in extroversion and openness) was observed in Italian (Favini et al., 2018) and Chinese adolescents (Xie et al., 2016), and the over-controlled type (high in agreeableness and conscientiousness) was observed in Finnish adolescents (Leikas & Salmela-Aro, 2014).

Patterns of Personality Development in Adolescence

While cross-sectional studies of personality types have been conducted, longitudinal studies of adolescent personality types remain limited. Three longitudinal studies in the Netherlands and Finland revealed adolescents’ patterns of personality development over five years. The studies conducted in both countries used latent class growth analysis, which is a special pattern of the growth mixture modeling (Jung & Wickrama, 2008), and identified three patterns of personality development in adolescence: resilient, under-controlled, and over-controlled (Branje et al., 2010; de Haan et al., 2013; Klimstra et al., 2010). The resilient pattern adolescents maintained a low level of neuroticism and high levels of the other four traits over time. The under-controlled pattern adolescents maintained high levels of extraversion compared to the other traits, and the over-controlled pattern adolescents continued to exhibit high levels of agreeableness compared to the other traits over time. The findings suggest that these three patterns of personality development are robustly observed among Dutch and Finnish adolescents.

The resilient, under-controlled, and over-controlled patterns are clearly distinguishable from one another in adolescence, and display distinct patterns of normative development (Klimstra et al., 2010). From ages 9 to 17, Finnish adolescents tend to show a decrease in each of the traits across all patterns (de Haan et al., 2013). In the Netherlands, each trait in the personality patterns tends to decline from approximately 12–16 years of age, and then increases through age 20 (Branje et al., 2010). Specifically, resilient adolescents tend to show an increase in openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness from ages 16–20. Under-controlled adolescents tend to increase in agreeableness and over-controlled adolescents tend to show a decrease in extraversion and an increase in conscientiousness from ages 16–20. Increased conscientiousness and decreased neuroticism are considered characteristics of the direction of personality maturation (Roberts et al., 2006). Therefore, these findings suggest that while the overall patterns in personality development do not change prominently throughout adolescence, the traits may change in the direction of maturity from middle to late adolescence onward (Soto et al., 2011).

Personality Development and Psychosocial Functioning

Psychosocial functioning includes life satisfaction, subjective happiness, and psychosocial problems (Diener et al., 1985). Furthermore, there are two types of psychosocial problems: internalizing and externalizing problems (Achenbach et al., 2016). Internalizing problems, such as depression and anxiety, are related to an individual’s internal environment; and externalizing problems, such as aggression and conduct problems, are related to an individual’s external environment. Previous studies on personality types in adolescents have revealed the personality types associated with different psychosocial functioning. The resilient type have higher levels of life satisfaction (Leikas & Salmela-Aro, 2014) and lower levels of depression and externalizing problems than other personality types (Xie et al., 2016), suggesting that the resilient type are adaptive in psychosocial functioning. The under-controlled type exhibit more externalizing problems than other personality types (Xie et al., 2016), suggesting that the under-controlled type may have externalizing problems from overreacting to the environment, while internalizing problems may not be as pronounced. The over-controlled pattern presents with more internalizing problems than other personality patterns (Klimstra et al., 2010). Contrary to the under-controlled type, the over-controlled type has strong ego-control, suggesting that individuals of this type may have internalizing problems, while externalizing problems may not be as pronounced. Regarding other personality types, the vulnerable type has the lowest life satisfaction (Xie et al., 2016) and the highest levels of depression, aggression, and alcohol consumption (Leikas & Salmela-Aro, 2014). This suggests that the vulnerable type may be the most at risk for poor psychosocial functioning. The psychosocial functioning of moderates falls between resilient and vulnerable overall and is generally poorer than that of the over-controlled type in terms of internalizing problems (Leikas & Salmela-Aro, 2014).

Japanese Contexts from Middle to Late Adolescence

Most studies identifying personality types have been conducted in Western countries; the only study conducted in the East was a cross-sectional study in China (Xie et al., 2016). Furthermore, the only studies that identified patterns in personality development and examined their relationship with psychosocial functioning were conducted in the Netherlands and Finland. To gather knowledge about changes in patterns of personality development during adolescence, it is necessary to clarify personality patterns that are common across countries as well as those that are country-specific. Japan, where the current study was conducted, is an Eastern country with a mix of individualism and collectivism (Sugimura, 2020). Furthermore, similar to China, Japan is also part of the East; however, even in the East, cultures and practices of individualism and collectivism tend to differ (Oyserman et al., 2002). Therefore, by focusing on the Japanese population, it is possible to identify patterns of personality development of adolescents that are culturally different from those of the Chinese population.

In Japan, education is compulsory up to middle school, with a high school enrollment rate of 98% and a retention rate of 2% (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2021a). Furthermore, among high school students, 54.9%, 24.0%, and 4.0% subsequently enroll in university (or junior college), vocational school, and specialized training college, respectively, and 17.1% enter the labor market or choose other careers (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2021b). Japanese adolescents attend junior high school from ages 12–15 and high school from ages 16−18. Then, at the age of 18, they make a career choice: pursue higher education or work. The period between the ages of 16 and 19 is a time when adolescents adjust to the high school setting, choose and decide on their next career path, and adjust to higher education institutions or work environments. Therefore, the most appropriate time to capture the pattern of personality development is during this period of environmental adjustment and transition to the next career path. In the school settings, Japanese adolescents are expected to cooperate with their surroundings rather than actively display their individuality (Hatano et al., 2022). Hence, in this context, it is possible to find more of the over-controlled pattern that suppresses their own needs and overreacts to the demands of their environment than other patterns.

Current Study

Personality types in adolescence are country-specific. Furthermore, even if the patterns of personality development are generally the same, there is a change in personality traits in each pattern. However, the findings in existing literature are limited to those studies conducted in the Netherlands and Finland. To fill this research gap, the present study aimed to identify patterns of personality development in Japanese adolescents and examine the relationship between personality patterns and psychosocial functioning. To achieve this, two objectives were set. The first was to identify patterns of personality development. As this is the first study to examine patterns of personality development among Japanese adolescents, an exploratory hypothesis was established and it was expected that all possible personality patterns would be identified (resilient, under-controlled, over-controlled, vulnerable, and moderate) (Hypothesis 1-a). Furthermore, owing to Japanese cultural characteristics, it was hypothesized that the proportion of the over-controlled pattern would be higher than other patterns (Hypothesis 1-b). The second objective was to examine the relationship between the pattern of personality development and psychosocial functioning. Based on Italian (Favini et al., 2018) and Chinese adolescent studies (Xie et al., 2016), it was expected that the resilient pattern would be associated with higher subjective well-being and lower internalizing and externalizing problems (Hypothesis 2-a). Additionally, it was expected that the under-controlled pattern would have higher externalizing problems than the other patterns (Hypothesis 2-b) and the over-controlled pattern would have higher internalizing problems than the other patterns (Hypothesis 2-c). As for the vulnerable pattern, it was expected that this pattern would have lower scores on subjective well-being and higher scores on internalizing and externalizing problems than the other patterns (Hypothesis 2-d). Furthermore, it was expected that both subjective well-being and psychological problems in the moderate pattern would fall between those of the resilient and vulnerable patterns (Hypothesis 2-e).

Methods

Participants

Participants in the first wave (T1) included 618 Japanese adolescents (49.5% girls) aged 16 years. In the second wave (T2), 438 adolescents participated (53.7% girls; 29.1% were missing). A total of 357 adolescents participated in the third wave (T3) (52.9% girls; 42.2% were missing), and 212 adolescents participated in the fourth wave (T4) (50.5% girls; 65.7% were missing). While 183 adolescents completed all four waves, the remaining 435 adolescents did not participate in at least one of the four waves, resulting in a data loss rate of 70.4% between T1 and T4.

Of these, 71.5% lived in the more urban parts of Japan (Kanto, Kansai, and Chubu districts), whereas the remaining 28.5% lived in the less urban parts of Japan (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu districts). Regarding family income, 14.9% came from a low-income background (less than 2 million yen), 50% came from a middle-income background (2–8 million yen), 23.9% came from a high-income background (over 8 million yen), and 4.1% reported unknown family income backgrounds. The percentage of the population by region in 2013 was 68.3% in relatively urban areas and 31.7% in less urban areas (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2014). The percentage of the family income in 2015 was as follows: 19.6% came from a low-income background (less than 2 million yen), 60.0% came from a middle-income background (2–8 million yen), and 20.2% came from a high-income background (over 8 million yen) (Annual Report on Health, Labour and Welfare, 2020). Therefore, these estimates closely represent the regional and family income statistics in Japan.

To examine the missing data pattern, Little’s (1988) Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test was conducted. The result [χ2(95) = 93.303, p = 0.530] showed that the missing data pattern was most likely completely random. Furthermore, chi-square tests were conducted to examine whether there was a difference in the percentages of sex, residential area, and income between those who responded to all the surveys and those who did not. The distribution did not differ significantly according to sex [χ2(1, N = 616) = 0.265, p = 0.607, Cramer’s V = 0.021, p = 0.607] and income [χ2(1, N = 560) = 0.993, p = 0.609, Cramer’s V = 0.042, p = 0.609], but it differed significantly according to residential areas [χ2(4, N = 618) = 8.813, p = 0.012, Cramer’s V = 0.119, p = 0.012]. However, the effect size was small (Cohen, 1988); hence, sex, region of residence, and income were not included in the analysis. All participants were included in the analyses, and the maximum likely robust estimation method was employed for the missing values.

Procedure

Data were obtained from the Japanese Longitudinal Identity Research Project (JLIRP) (Hatano et al., 2020), which consisted of four waves conducted between March 2013 and March 2016 with one-year assessment intervals. Personality traits and subjective well-being scales were administered in all surveys, and the psychosocial problems scale was administered in March 2014 (T2), March 2015 (T3), and March 2016 (T4). In Japan, the fiscal year begins in April and ends in March. Therefore, March was considered an appropriate time to experience life according to each fiscal year (e.g., high school freshman). Furthermore, the period from 2014 to 2016 was before the behavioral restrictions associated with the spread of the COVID-19 infection were enforced (i.e., March 2020).

For the JLIRP, the online research company MACROMILL (http://www.macromill.com/) was used to collect data. A large number of people are registered with this research company and are remunerated for participating in surveys. MACROMILL is the survey company with the largest number of registered respondents in Japan. The company periodically recruits monitors to participate in surveys, and monitors must provide information on their age, sex, family member status, household income status, socioeconomic status, and residential area. MACROMILL collects data according to the client’s requirements. The specifications for the JLIRP project were as follows: (1) participants should be Japanese; (2) adolescents aged 16; and (3) data for 600 people must be collected. Since 16-year-old adolescents are minors and could not be registered with the company, the target group consisted of adults with children aged 16. First, MACROMILL contacted the registrants (i.e., adults) with an outline of the survey and asked for their informed consent. Registrants and their children who agreed to participate in the survey received an email with a URL to the survey form (to be completed by the children). Those who participated in the survey were paid 50 JPY (approximately 0.50 USD in 2013) as compensation.

Measures

Personality traits

The Big Five personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) were assessed using the Japanese version of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Yoshimura et al., 1998). It consists of 60 items that assess the five personality traits (12 items for each subscale rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = completely untrue to 5 = completely true). The Cronbach’s alpha value ranges across the four waves were as follows: 0.82 to 0.84 for neuroticism; 0.78 to 0.84 for extraversion; 0.37 to 0.50 for openness; 0.59 to 0.68 for agreeableness; and 0.72 to 0.80 for conscientiousness.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985), which consists of five items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely untrue to 5 = completely true; e.g., “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”). Cronbach’s alpha values across the four waves ranged from 0.84 to 0.90

Subjective happiness

Subjective happiness was assessed using the Japanese version of the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999; Shimai et al., 2004). This scale consists of four items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely untrue to 5 = completely true; e.g., “Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself happier”). Cronbach’s alpha values across the four waves ranged from 0.68 to 0.90.

Psychosocial problems

Internalizing and externalizing problems were assessed using the self-report version of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997). This measure includes 25 items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). To achieve the research objectives, 20 items from four subscales were used: 10 items for emotional symptoms (e.g., “I worry a lot”) and peer problems (e.g., “Other children or young people pick on me or bully me”) that assessed internalizing problems, and 10 items for conduct problems (e.g., “I am constantly fidgeting or squirming”) and hyperactivity (e.g., “I find it difficult to concentrate”) that assessed externalizing problems. Cronbach’s alpha values across the three waves ranged from 0.83 to 0.86 for internalizing problems and 0.80 to 0.84 for externalizing problems.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of structural equation models were conducted using Mplus 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2021). As a preliminary analysis, a measurement invariance test of personality traits was conducted over time. For structural equation modeling using longitudinal data, the factor structure of the used scales should be identical (Little, 2013). Therefore, three models were tested in the measurement invariance test: a configural invariance model (in which the number of factors and pattern of fixation were the same across all time points and the factor loadings were freely estimated), a metric invariance model (in which the number of factors, pattern of fixation, and factor loadings were the same across all time points), and a scalar invariance model (constraining the indicator factor loading and item intercepts to be equal across all time points). When the full metric or scalar invariant models were not supported, additional analyses to test partial measurement invariance (when some but not all factor loadings or item intercepts are equal overtime) were performed. Partial or full scalar invariance should be established to estimate the trajectories of the study variables (Little, 2013). Furthermore, the item parceling approach was used for confirmatory factor analysis. Parceling is recommended in situations in which the scale has more than five items for each construct and the sample size is large (Bagozzi & Heatherton, 1994). Using a large number of indicators in confirmatory factor analysis often results in numerous correlated residuals, which decreases both the fit of the model and the utility of the latent variable in capturing the construct of interest (Marsh et al., 1998). Thus, parcels of items were constructed in a random fashion and used as indicators of the latent variables. Specifically, three parcels (i.e., combining four items) were loaded on each personality factor.

For optimal model fit, comparative fit index (CFI) values higher than 0.90 were considered acceptable; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values less than 0.08 indicated a reasonable fit (Kline, 2015).To test whether the fit of the model was equivalent across time, differences in the Satorra-Bentler χ2 difference test (S-Bχ2; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), CFI (ΔCFI), and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) between models were used. If the differences in model fit indices exceeded the following criteria, the null hypothesis of invariance was rejected: significant changes in S-Bχ2 at p < 0.05, ΔCFI ≥ 0.010 and ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015 (Kline, 2015).

To accomplish the first study objective, latent class growth analysis (LCGA; Nagin, 2005) was used. LCGA summarizes longitudinal data by modeling individual-level variability in developmental trajectories through a small number of classes set by inter-individual differences (intercepts) and intra-individual differences (slopes (Nagin, 2005)). LCGA is a special type of growth mixture modeling in which several latent subclasses are estimated in the population based on the intercepts and slopes estimated in the latent growth model. LCGA assumes that the variances and covariances of the intercept and slope factors within each of its subclasses equal to zero. With this assumption, the growth trajectories of all individuals within each subclass are assumed to be uniform (Jung & Wickrama, 2008). The following statistical indicators were used to determine the number of latent classes: sample size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SSABIC), bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (Nylund et al., 2007), and entropy. A lower SSABIC value indicates a better fit of the model, and a significant bootstrapped ratio test score indicates that a model with k classes fits better than a model with k-1 classes. Entropy ranges from 0.00 to 1.00, with values greater than or equal to 0.75 indicating accurate classification (Reinecke, 2006). In addition to these criteria, the number of classes was determined based on interpretability (Young & Wickrama, 2008), with at least 5% of the sample being in one class. According to these criteria, the class solutions 1 to 5 were compared and the most parsimonious class solution was selected.

Regarding the second study objective, the association between the identified personality type trajectories and psychosocial functioning was examined. To take advantage of the characteristics of the longitudinal data, the intercepts and slope latent scores of psychosocial functioning were calculated by a series of latent growth model (LGM; McArdle & Epstein, 1987). Then, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with personality types’ trajectories as independent variables and the factor scores of the intercepts and slope in each psychosocial functioning indicator as dependent variables. M-plus was used for the LCGA and LGM, and SPSS (version 25.0) was used for other all analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics, Rank-Order Stability, and Measurement Invariance Tests

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and rank-order stability for each variable. For all variables, rank order stability was moderate to high (rs = 0.40–0.73; p < 0.001). Furthermore, measurement invariance tests across time points were conducted for each personality trait (Table S1). Although full scalar invariance was established for extraversion and agreeableness, it was not established for neuroticism, openness, and conscientiousness. Partial scalar invariance was then examined by removing the restriction of one parcel intercepts for each of the following: neuroticism, openness, and conscientiousness. The results showed that the modification indices met the criteria for all three traits (Table S1). Consequently, full or partial scalar invariance across all time points was established for all personality traits.

Correlations Between Personality Traits and Psychosocial Functioning

Table 2 presents values representing correlations between personality traits and psychosocial functioning during T1, T2, T3, and T4. In general, neuroticism was negatively related to subjective well-being and positively related to psychosocial problems. Extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness were positively related to subjective well-being and negatively related to psychosocial problems. Openness was positively related to subjective well-being and negatively related to externalizing problems.

Patterns of Personality Development

To identify patterns of personality development, LCGA was performed for all personality traits. From the criteria stated in the Statistical Analysis sections, under Methods, the 2-5 solutions fit the data (Table 3). From the SSABIC and entropy, a 5-class solution was acceptable. For the 5-class solution, one class included less than 5% of the number of participants (i.e., 1.5%) (Table 4). In addition, a pattern was identified in the 4-class solution that was not found in the 3-class solution (Table S2). Consequently, the 4-class solution was selected.

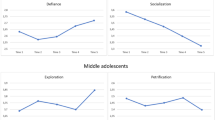

Table 5 and Fig. 1 present the means of intercepts and slopes for all classes. Class 1 (N = 65; 10.5% of participants) consisted of individuals who achieved a relatively high score on extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness; a moderate score on openness; and a low score on neuroticism. This was interpreted as the resilient pattern. Class 2 (N = 79; 12.8% of participants) consisted of individuals who achieved a high score on agreeableness; a moderately high score on extraversion, openness, conscientiousness; and a moderate score on neuroticism. This was interpreted as the over-controlled pattern. Class 3 (N = 59; 9.6% of participants) consisted of individuals who achieved a relatively high score on neuroticism, a moderate score on agreeableness and openness, and a low score on extraversion and conscientiousness. This was interpreted as the vulnerable pattern. Class 4 (N = 415; 67.2% of participants) consisted of individuals who scored moderately on all personality traits. This was interpreted as the moderate pattern.

Regarding the change in personality traits in each pattern, resilient and over-controlled adolescents did not change in all traits. Vulnerable adolescents increased in conscientiousness, and moderate adolescents decreased in neuroticism and increased in conscientiousness.

Associations Between Patterns of Personality Development and Psychosocial Functioning

To examine the associations between personality types and psychosocial functioning, first, the factor scores of the intercepts were determined by using LGM (Table S3). For externalizing problems, the solution did not converge; hence, the mean score of the T2–T4 externalizing problems was calculated. Second, MANOVAs were conducted with pattern of personality development as independent variables and the factor scores of the intercepts in psychosocial functioning as dependent variables [for subjective well-being: F(4,611) = 22.316, λ = 0.667, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.126; for psychosocial problems: F(3,179) = 25.60, λ = 0.356, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.291] (Tables 6 and 7).

For the factor scores of intercepts in life satisfaction and subjective happiness, the resilient and over-controlled patterns had the highest scores, followed by the moderate pattern; the vulnerable pattern scored the lowest. For the factor scores of the slope in life satisfaction, the vulnerable pattern was higher than the resilient and moderate patterns. For the factor scores of the slope in subjective happiness, the vulnerable and moderate patterns were higher than the resilient pattern. For the score of intercepts in internalizing problems, the vulnerable pattern was the highest, followed by the moderate, over-controlled, and resilient patterns. For the mean score in externalizing problems, the vulnerable and moderate patterns had the highest scores, followed by the over-controlled pattern; the resilient pattern scored the lowest.

Discussion

Personality types are strongly associated with psychosocial functioning. Specifically, longitudinal studies have revealed the relations between patterns of personality development and psychosocial functioning over time, thereby enabling the prediction of adaptation or maladaptation of psychosocial functioning in adolescents. To date, studies examining the association between patterns of personality development and psychosocial functioning have been limited to the Netherlands and Finland. To provide further evidence on personality development in Japanese adolescents, the present study identified four patterns in personality development: resilient, over-controlled, vulnerable, and moderate. Furthermore, psychosocial functioning differed from the patterns of personality development.

Patterns of Personality Development in Japanese Adolescents

Four of the five predicted personality patterns were identified, partially supporting Hypothesis 1-a. The resilient pattern was identified, and 10.5% of the adolescents in the study sample were classified as this pattern. This type was characterized by low neuroticism, moderate openness, and high levels of other traits throughout the four years. Adolescents of the resilient pattern are more mature than other patterns because of their low neuroticism and relatively high levels of other traits. Over-controlled was another pattern that was observed and was characterized by high levels of agreeableness and moderate neuroticism; 12.8% of adolescents in this study were classified as this pattern. Compared to the resilient pattern, over-controlled adolescents had moderately high levels of agreeableness throughout the four years. In other words, this pattern of adolescents could be overly sensitive and overemphasize their surroundings. In this study, 8.5% of the adolescents were classified as vulnerable. The vulnerable pattern scored high on neuroticism and lower on the other four traits throughout the four years. It may be a risky personality pattern regarding psychosocial functioning because of its high levels of maladaptive (i.e., neuroticism) and low levels of adaptive personality traits (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness). The moderate pattern was characterized by average scores on all the personality traits throughout the four years. This pattern of adolescents represent a moderate degree of self-consciousness about all personality traits.

Interestingly, 67.2% of the adolescents in the current study were classified as moderate; hypothesis 1-b was not supported. More than half of the adolescents in the samples in previous studies in which this type was observed were classified as moderate: 55% in Italy (Favini et al., 2018), 64% in China (Xie et al., 2016), and 51% in Finland (Leikas & Salmela-Aro, 2014). The present findings are consistent with these studies, suggesting that moderate may be a representative pattern of personality development among Japanese adolescents. In a Chinese study, the authors attributed the high rate of the moderate type to the fact that education in China emphasizes social norms, which makes all characteristics “moderate” (Xie et al., 2016). This is similar to Japan; Japanese adolescents tend to act in accordance with their surroundings, rather than asserting their individual opinions in a school setting (Hatano et al., 2022). Furthermore, in a school setting where they are not actively assertive, their perception of self may be moderate and it may be difficult for them to view themselves generally as positive (i.e., resilient) or negative (i.e., vulnerable). This environment and self-perception may be the reason why the resilient pattern was less frequent than in other studies (approximately 36.5% in the Netherlands; Branje et al., 2010) and why the under-controlled pattern was not identified.

Regarding the change in traits for each pattern, while resilient and over-controlled adolescents showed no change in traits, vulnerable adolescents showed an increase in conscientiousness, and moderate adolescents showed a decrease in neuroticism and an increase in conscientiousness. These results suggest that the adolescents with non-mature patterns of personality development might be changing toward a more mature direction than adolescents with other patterns. In Japan, high school students are required to be diligent in school settings (such as with studying and club activities) to enter higher education or secure employment (Hatano & Sugimura, 2017). In this school setting, there is no room for growth for diligent adolescents, whereas there is still room for those who are not so to become diligent. These findings generally support the theory that personality traits move toward maturity, which begins in middle adolescence (Soto et al., 2011).

Associations among Patterns of Personality Development and Psychosocial Functioning

Resilient adolescents had higher intercept scores on life satisfaction and subjective happiness and lower scores on psychosocial problems than the other types. These findings supported Hypothesis 2-a. Furthermore, these results are consistent with previous studies, suggesting that the resilient pattern is psychosocially healthy and that this trend may persist over four years.

Over-controlled adolescents in the current study’s sample had the same level of scores for intercepts on life satisfaction and happiness as resilient adolescents, while their psychosocial problems tended to be higher. These findings supported Hypothesis 2-c. Over-controlled individuals have excessive ego-control and more pronounced internalizing problems than the other patterns (Klimstra et al., 2010). This finding is consistent with previous studies, suggesting that over-controlled adolescents may have more internalizing problems than resilient adolescents in Japan.

As expected, the vulnerable pattern had the lowest intercept scores on subjective well-being and the highest psychosocial problems compared to the other patterns. This result supported Hypothesis 2-d and suggested that the vulnerable pattern is the most at-risk type for problems with psychosocial functioning, which could persist. Although the vulnerable pattern was previously found in cross-sectional studies, the present study identified this in longitudinal data and showed that the vulnerable pattern did not change over the four years of adolescence in Japan.

Psychosocial functioning for the moderate pattern fell between that of the resilient, over-controlled, and vulnerable types. This finding supported Hypothesis 2-e and suggested that moderate adolescents may feel life satisfaction and happiness, but also experience moderate levels of psychosocial problems. Meanwhile, their scores on externalizing problems were as high as those of the vulnerable pattern. Given that the highest number of adolescents were classified as moderate, the results of this study suggest that adolescence in Japan may be a period of increased risk for externalizing problems. Adolescents may have difficulties coping with their environment and externalizing problems as individuals become psychologically independent from their parents (Beyers et al., 2003). These findings suggest the importance of identifying maladaptive characteristics of Japanese adolescents in the external environment to improve psychosocial functioning.

Developmental Implications

The present findings provide valuable implications for personality development in adolescence. First, this study identified patterns of personality development in Japanese adolescents, noting four patterns: resilient, over-controlled, vulnerable and moderate. Of these, the vulnerable and moderate patterns had not previously been identified, and are immature patterns compared to the resilient and over-controlled patterns. Furthermore, the present findings revealed that Japanese adolescents with vulnerable and moderate patterns tend to move toward maturity. These findings suggest that adolescents with non-mature personality patterns may move toward maturity as they adjust to the high school environment and make career choices. The present study provides evidence of patterns of personality development in Japanese adolescents similar to previous studies in the Netherlands and Finland.

Second, this study (in comparison with a previous one) showed that the patterns of personality development differed between China and Japan, thus indicating differences even within countries in the same Eastern region. This study identified four patterns of personality development, three of which were the same as those found in a Chinese study (Xie et al., 2016). Furthermore, this study identified an over-controlled pattern, which was not identified in China. Conversely, an under-controlled type, which was identified in China, was not identified. These differences suggest that patterns of personality development may differ between China and Japan. The findings of this study contribute to the evidence that diverse patterns of personality development across cultures and societies are not dichotomized between Eastern and Western countries (Oyserman et al., 2002).

Third, the present findings revealed which pattern of personality development were psychosocially healthy or unhealthy in Japanese adolescents. Resilient adolescents are psychosocially healthy, over-controlled adolescents have internalizing problems, vulnerable adolescents are psychosocially unhealthy, and moderate adolescents have externalizing problems. Furthermore, these personality patterns did not change from middle to late adolescence. Vulnerable adolescents may be particularly psychosocially unhealthy for four years. These findings provide longitudinal evidence for the relationship between persistent personality development and psychosocial problems in Japan.

Limitations and Future Directions

The limitations of this study are as follows: first, all measures in this study were self-reported. While self-report is a powerful way to measure personality traits and psychosocial functioning, research using other forms of reporting is also required to provide more robust evidence. In the future, the degree of agreement between self-assessment and peer assessment should be examined. Second, the Cronbach’s alpha values for openness and agreeableness were low, and internal consistency was problematic. In the future, it is necessary to examine whether the findings of this study can be replicated using another Big Five personality scale, such as the Big Five Inventory (Soto & John, 2017). Third, the attrition rate of the participants was high. This may be because of the minimal compensation provided for participation, although this amount is typical in the context of research norms in Japan. In the future, it is important to devise a way to increase the amount of reward so that the survey collaborators continuously participate in the survey. Fourth, the replicability of the results of this study must be examined. In the future, it will be necessary to examine whether the personality types identified in this study can be identified in other samples and whether they show similar results in relation to psychosocial functioning. Fifth, the present study used data collected prior to the impact of behavioral restrictions due to the spread of COVID-19. Japan imposed major economic and daily activity restrictions in March 2020. While these restrictions were eased to some extent in 2022, restrictions such as wearing masks at school and not talking loudly are still imposed. Therefore, the personality traits of adolescents experiencing such behavioral restrictions may be more neurotic, more extraverted, and less open, differing from the trends observed in this study. Such differences may lead to an increase in the vulnerable pattern and the identification of other different patterns. Future studies are needed to identify patterns of personality development and their relationship to psychological functioning based on data from March 2020 onward.

Conclusions

While patterns of personality development may vary across countries, previous research has been limited to studies in the Netherlands and Finland. To address this research gap, this study examined patterns of personality development and their association with psychosocial functioning from middle to late adolescence in Japan. The LCGA results of this study identified four patterns of personality development: resilient, over-controlled, vulnerable, and moderate. Specifically, the moderate pattern was the most common, indicating that this pattern may be representative of Japanese adolescents. Although the overall patterns of personality development did not change markedly across the four years, adolescents with non-mature vulnerable and moderate patterns tend toward maturity. Furthermore, the relationship between these patterns and psychosocial functioning indicated that resilient adolescents were closely associated with healthy psychosocial functioning, vulnerable adolescents were most at risk for problems with psychosocial functioning, over-controlled adolescents were at risk of internalizing problems, and moderate adolescents were most likely to have externalizing problems. These findings show the unique characteristics of patterns of personality development in Japan. Moreover, these outcomes contribute to adolescent personality research.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Rescorla, L. A., Turner, L. V., & Althoff, R. R. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(8), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012.

Alessandri, G., Vecchione, M., Donnellan, B. M., Eisenberg, N., Caprara, G. V., & Cieciuch, J. (2014). On the cross-cultural replicability of the resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled personality types. Journal of Personality, 82(4), 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12065.

Annual Report on Health, Labour and Welfare (2020). Population and households, Retrieved from https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2013np/

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15(3), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.408.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Structural equation modeling: A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self‐esteem. Structural Equation Modeling, 1, 35–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519409539961.

Beyers, J. M., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & Dodge, K. A. (2003). Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1–2), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023018502759.

Bleidorn, W., et al. (2020). Longitudinal experience–wide association studies—A framework for studying personality change. European Journal of Personality, 34(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2247.

Block, J. (1971). Lives through time. Berkeley, CA: Bancroft.

Block, J. H., & Block, J. (1980). The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), Development of cognition, affect, and social relations: The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 13) (pp. 39–103). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Branje, S. J. T., Hale, III, W. W. H., Frijns, T., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Longitudinal associations between perceived parent–child relationship quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9401-6.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Costa, P. T. Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory and five factor inventory professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

de Haan, A. D., Deković, M., van den Akker, A. L., Stoltz, S. E. M. J., & Prinzie, P. (2013). Developmental personality types from childhood to adolescence: Associations with parenting and adjustment. Child Development, 84(6), 2015–2030. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12092.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Favini, A., Gerbino, M., Eisenberg, N., Lunetti, C., & Thartori, E. (2018). Personality profiles and adolescents’ maladjustment: A longitudinal study. Personality and Individual Differences, 129, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.016.

Ferguson, S. L., & Hull, D. M. (2018). Personality profiles: Using latent profile analysis to model personality typologies. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.029.

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48(1), 26–34.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x.

Hatano, K., Hihara, S., Sugimura, K., & Crocetti, E. (2022). Direction of associations between personality traits and educational identity processes: Between- and within-person associations. Journal of Adolescence, 94(5), 763–775. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12062.

Hatano, K., & Sugimura, K. (2017). Is Adolescence a period of identity formation for all youth? Insights from a four-wave longitudinal study of identity dynamics in Japan. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2113–2126. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000354.

Hatano, K., Sugimura, K., Crocetti, E., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2020). Diverse-and-dynamic pathways in educational and interpersonal identity formation during adolescence: Longitudinal links with psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 91(4), 1203–1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13301.

Hill, P. L., & Edmonds, G. W. (2017). Personality development in adolescence. In J. Specht (Ed.), Personality development across the lifespan (pp. 25–38). London, UK: Academic Press.

Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x.

Klimstra, T. A., Akse, J., Hale, W. W., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Longitudinal associations between personality traits and problem behavior symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(2), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.02.004.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Leikas, S., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Personality types during transition to young adulthood: How are they related to life situation and well-being? Journal of Adolescence, 37(5), 753–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.01.003.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., Balla, J. R., & Grayson, D. (1998). Is more ever too much? The number of indicators per factor in confirmatory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 33(2), 181–220. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3302_1.

McArdle, J. J., & Epstein, D. (1987). Latent growth curves within developmental structural equation models. Child Development, 58(1), 110–133. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130295.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2021). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles (7th ed.). CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3.

Reinecke, J. (2006). Longitudinal analysis of adolescents’ deviant and delinquent behavior. Methodology, 2(3), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241.2.3.100.

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality trait across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1.

Schwartz, S. J., & Petrova, M. (2018). Fostering healthy identity development in adolescence. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(2), 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0283-2.

Shimai, S., Otake, K., Utsuki, N., Ikemi, A., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2004). Development of a Japanese version of the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), and examination of its validity and reliability. [Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi] Japanese Journal of Public Health, 51(10), 845–853. https://doi.org/10.11236/jph.51.10_845.

Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2017). The next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000096.

Soto, C. J., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2011). Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 330–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021717.

Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2014). Statistical handbook of Japan, Retrieved from https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/pdf/2014all.pdf

Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2021a). School basic survey, Retrieved from https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/kaikaku/20210315-mxt_kouhou02-1.pdf

Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2021b). School basic survey, Retrieved from https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20211222-mxt_chousa01-000019664-1.pdf

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83.

Sugimura, K. (2020). Adolescent identity development in Japan. Child Development Perspectives, 14(2), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12359.

Van den Akker, A. L., Deković, M., Asscher, J. J., Shiner, R. L., & Prinzie, P. (2013). Personality types in childhood: Relations to latent trajectory classes of problem behavior and overreactive parenting across the transition into adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 750–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031184.

Xie, X., Chen, W., Lei, L., Xing, C., & Zhang, Y. (2016). The relationship between personality types and prosocial behavior and aggression in Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.002.

Yoshimura, K., Nakamura, K., Ono, Y., Sakurai, A., Saito, N., Mitani, M., & Asai, M. (1998). Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the NEO five factor inventory (NEO‐FFI): A population based survey in Aomori prefecture. The Japanese Journal of Stress Sciences, 13, 45–53.

Authors’ contributions

K.H. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript; S.H. conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript; K.S. conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript; T.K. conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing and declaration

This manuscript’s data will not be deposited. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hatano, K., Hihara, S., Sugimura, K. et al. Patterns of Personality Development and Psychosocial Functioning in Japanese Adolescents: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study. J Youth Adolescence 52, 1074–1087 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01720-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01720-3