Abstract

Although community violence and the deleterious behavioral and psychological consequences that are associated with exposure to community violence persist as serious public health concerns, identifying malleable factors that increase or decrease adolescents’ risk of exposure to community violence remains a significant gap in our knowledge base. This longitudinal study addresses this research gap by investigating adolescents’ endorsement of familismo values and participation in three types of after-school activities, specifically home-, school-, and community-based activities, as potential precursors to adolescents’ risk for experiencing community violence. The sample consists of 416 Latino high school students (53% female) with a mean age of 15.5 years (SD = 1.0) and with 85% qualifying for free and reduced school lunch. Cross-sectional results demonstrated that adolescents’ endorsement of the Latino cultural value of familismo was associated with lower rates of personal victimization. The frequency of non-structured community-based activities and part-time work were concurrently associated with higher rates of witnessing community violence and being personally victimized by violence. Only the frequency of non-structured community-based activities was related to witnessing more community violence and greater victimization one year later while controlling for prior exposure to violence. These findings underscore the importance of providing structured, well supervised after-school activities for low-income youth in high-risk neighborhoods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many adolescents living in urban areas are exposed to alarmingly high rates of community violence, such that exposure to community violence presents a pressing public health crisis in the United States. The negative psychological and behavioral consequences experienced by adolescents exposed to urban violence and the higher rates of victimization among 12- to 15-year-old youth, compared to other age groups, makes adolescence a particularly important developmental period to study in relation to community violence (Cooley-Strickland et al., 2009; Fowler et al., 2009). While researchers have investigated factors that buffer youth from the aftermath of experiencing community violence (Hardaway et al., 2012), identifying malleable factors that increase or decrease adolescents’ risk of exposure to community violence remains a significant gap in our knowledge base. Indeed, researchers have identified demographic characteristics that are associated with adolescents’ exposure to community violence; for instance, African American youth and adolescents from poor families are more likely to experience community violence (Gibson et al., 2009; Goldner et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2003). However, there is a need to move beyond demographic characteristics. In this vein, the present study examines more malleable factors that can be targeted in interventions and investigates whether participation in different types of after-school activities is differentially related to exposure to community violence among urban, Latino adolescents. More specifically, this study examines the linkages between adolescents’ participation in home-based, school-based, and community-based activities as well as adolescents’ endorsement of familismo, a widely-held Latino cultural value, and risk of exposure to community violence.

Although Latino youth are disproportionately represented among youth living in poverty and are also likely to reside in urban, high-crime neighborhoods (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2007), far less is known about exposure to community violence among Latino youth compared to their African American counterparts. Moreover, not all youth who live in poor, urban neighborhoods are exposed to high levels of violence, and surprisingly little is known about the factors that place youth at risk for community violence in the first place. Since most exposure to violence and victimization among youth occurs in the afternoon and evening hours, beginning after school at 3 pm (Newman et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2015), this study examines Latino adolescents’ after-school activity participation as a precursor to exposure to community violence with a longitudinal research design.

The present study is guided by developmental-ecological theories (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993) which highlight ongoing, reciprocal relations between individual adolescents and the settings where as well as the people with whom they spend their time. In Cicchetti and Lynch’s (1993) ecological-transactional model of community violence, risk and protective factors may be present at any level of a child’s ecology (e.g., microsystem, macrosystem, exosystem). While characteristics of the proximal environment are likely to have the strongest effects on developmental outcomes and events, the model posits that factors in more distal levels of an adolescent’s ecology may similarly influence developmental outcomes as well as increase or decrease the likelihood of community violence. Risk and protective factors may influence violent events such that after-school activity characteristics in the exosystem (e.g., frequency of participation in activities) and cultural values or beliefs in the macrosystem (e.g., endorsement of familismo) may increase or decrease adolescent’s exposure to community violence as well as adolescents’ adaptation in response to violence.

A preponderance of evidence indicates that adolescents’ participation in structured after-school activities is associated with an array of positive developmental outcomes, including fewer academic difficulties, depressive symptoms, externalizing problem behaviors, and substance use (Bohnert et al., 2009; Farb & Matjasko, 2012; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Haghighat & Knifsend, 2019; Neely & Vaquera, 2017). Much of this research has been conducted with youth in suburban, middle- to upper-income, European American families (Pedersen & Seidman, 2005). Yet, evidence demonstrates that African American and Latino youth and youth from low-income families participate in far fewer structured, organized activities compared to their European American and higher-income counterparts (Bohnert et al., 2008; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012; Meier et al., 2018). Thus, it is imperative that researchers comprehensively assess the different types of activities in which racial/ethnic minority youth engage during the after-school hours. This study addresses this need by comprehensively assessing Latino adolescents’ participation in both structured and non-structured after-school activities, within multiple settings, including home, school, and community contexts. Further, this study examines the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between adolescent’s participation in different types of activities and exposure to community violence.

Familismo, Home-Based Activities, and Exposure to Community Violence

Given that racial/ethnic minority adolescents and youth from low-income homes participate in organized, structured activities at lower rates than their counterparts (Pedersen & Seidman, 2005), researchers must examine the non-structured activities in which many adolescents spend their time, including activities that occur in home settings. Among adolescents who, for various reasons, may be less engaged in school- and community-based extracurriculars, it is important to understand what activities occupy their time at home and how such activities may be associated with greater or lesser risk of exposure to community violence. Familismo, defined as incorporating an emphasis on family unity, cohesion, and loyalty above individual needs, is a widely endorsed cultural value among Latino families (Calzada et al., 2010; Halgunseth et al., 2006). Moreover, Latino adolescents’ endorsement of familismo has been linked to lower levels of exposure to community violence in prior studies (Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013). Since familismo encourages youth to spend more time with their families in home contexts (Leavell et al., 2012), it may be that familismo values reflect adolescents’ inclination to spend time at home engaged in familial obligations and responsibilities (Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013). This study directly tests this proposition and examines both endorsement of familismo values and home-based activities as precursors to Latino adolescents’ exposure to community violence. When accounting for both familismo and home-based activities, it is expected that home-based activities, rather than familismo values, will be associated with lower risk of exposure to community violence.

Some evidence for the hypothesis that home-based activities will be associated with lower rates of exposure to community violence is provided by studies with urban, African American youth. Richards and colleagues (2004), for example, reported that time spent with family was associated with less exposure to community violence among African American adolescents. Adolescents in their study reported on their activities in actual time via experience sampling methods. Relatedly, among African American adolescents, Hammack and colleagues (2004) found that time spent with family buffered adolescents from the negative psychological impact of community violence. Hence, in this sample of Latino adolescents, it is expected that greater participation in home-based activities will be cross-sectionally and longitudinally associated with lower rates of exposure to community violence.

School-Based Activities and Exposure to Community Violence

Although research in this area is quite sparse, some evidence indicates that participation in structured, school-based activities may reduce levels of exposure to community violence among adolescents who are at risk of exposure. Among urban, African American adolescents, Richards and colleagues (2004) found that participation in structured activities was associated with less exposure to community violence and fewer associated symptoms of distress. Relying upon experience sampling methods, the authors defined structured free time activities as including time spent on homework, extracurriculars, and creative activities. Some of these activities, like time spent doing homework and certain extracurriculars, were most certainly school-based activities. By engaging youth in activities that are supervised by adults and/or that require frequent concerted effort over sustained amounts of time (e.g., daily after-school sports practices and games; homework assignments), participation in structured, school-based activities may protect youth from spending time in risky neighborhood settings where violence is more likely to occur. School-based activities may also increase adolescents’ sense of school belonging and academic engagement, perhaps promoting more time spent on homework and other school projects that are conducted at home. Moreover, many high schools require that students maintain a grade point average above a certain cut-off in order to participate on school sports teams. Thus, it is expected that more time spent on school-based activities will be related to lower rates of exposure to community violence both concurrently and over time.

Community-based Activities and Exposure to Community Violence

In some neighborhoods, the mere presence of community centers may reflect a sense of shared collective efficacy and commitment to supporting the common good among community residents and families. Indeed, one study found that the presence of recreation centers, for example, was linked to lower rates of violent crime in economically poor neighborhoods (Peterson et al., 2000). Consequently, in poor neighborhoods, community-based activities may serve as a protective, informal monitoring mechanism for youth. Alternatively, community centers that provide little supervision or structure may negatively influence youth and permit more exposure to violence in the community, reflecting a lack of collective efficacy among neighborhood residents. Bohnert and colleagues (2009) define structured activities as those that are organized and facilitated by a club, program or organization that provides general guidelines for participation; conversely, non-structured activities have no formal guidelines or leadership and are not facilitated by an organization. A strength of the current study is the consideration of adolescents’ participation in both structured as well as non-structured community-based activities.

Some prior evidence indicates that participation in structured community-based activities is associated with greater risk of exposure to community violence. In a cross-sectional study of Latino adolescents, participation in organized non-school clubs and non-school sports were associated with greater victimization and witnessing community violence; however, adolescents’ participation in volunteer organizations and religious groups were not related to exposure to community violence (Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013). In accord with these findings, Camacho-Thompson and Vargas (2018) found that Latino (primarily Mexican American) adolescents’ participation in structured community activities was associated with witnessing more community violence, and these relations were similar for both boys and girls. Even when community activities are organized, well structured, and supervised by adults, it may be that spending more time in high-risk neighborhoods, traveling to and from activities, increases adolescents’ opportunities to witness or be victimized by violence. Further, non-school clubs and sports activities in the community may heighten opportunities for unstructured socializing with peers and may occur in particularly risky, high-crime neighborhood areas. It is also possible that adolescents who experience high rates of exposure to community violence consequently seek out community activities as “safe havens” to mitigate their exposure to violence. However, the cross-sectional design of prior studies precluded examination of the direction of effects. Therefore, the current study expands on prior findings by using longitudinal data to determine whether community activity participation does, in fact, precede increases in adolescents’ exposure to community violence.

While it is developmentally appropriate for adolescents to seek greater autonomy from parents and adult authority figures, studies indicate that, in dangerous neighborhood settings, adolescents’ participation in non-structured activities, such as hanging out with friends, is related to negative developmental outcomes (Bohnert et al., 2009; Mahoney & Stattin, 2000). In a similar vein, participation in non-structured, community-based activities may place youth at greater risk for exposure to violence. Among a large sample of Latino, African American, and European American youth residing in Chicago neighborhoods, unstructured socializing with peers (without adult supervision) was associated with greater risk of exposure to community violence (Antunes and Ahlin 2018). Likewise, spending unstructured leisure time with friends and holding a part-time job were concurrently associated with greater exposure to community violence, as both witnesses and victims of violence among a sample of Latino youth (Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013). Unstructured socializing with peers is likely to occur outside in neighborhood settings and also likely to coincide with little adult supervision, allowing for greater exposure to violence and contact with “deviant” peers. Adolescents who hold part-time jobs may be more likely to spend time going to and from employment sites during evening hours when violence is more likely to occur. Similar results for non-structured activities have been reported with African American adolescents. Utilizing experience sampling methods, Richards and colleagues (2004) found that time spent in unsupervised and unstructured contexts with peers was linked to greater risk for both victimization and witnessing violence.

A strength of the current study is the inclusion of both structured and non-structured community-based activities in examining the association between community-based activities and adolescents’ risk for exposure to community violence. Importantly, community-based activities are not all categorized as the same and notable differences in the characteristics associated with these activities are considered. It is expected that positive associations will be found between more frequent participation in non-structured community-based activities as well as part-time employment and greater levels of exposure to community violence. Specifically, this study tests the hypothesis that adolescents’ participation in non-structured, rather than structured, community-based activities, and part-time employment will be related to greater rates of exposure to community violence both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, one year later.

Current Study

Identifying malleable factors that may increase or decrease adolescents’ risk of exposure to community violence is a pressing research question with far-reaching public health implications. The present longitudinal study addresses this important gap in our knowledge base by investigating adolescents’ endorsement of familismo values and participation in different types of after-school activities as potential precursors to adolescents’ risk for experiencing community violence. The overarching aims of the present study are twofold. The first aim is to test whether endorsement of the Latino cultural value of familismo is directly associated with exposure to community violence, as seen in prior cross-sectional studies, when also accounting for adolescents’ home-based activities. More specifically, the first hypothesis proposes that greater endorsement of familismo will be associated with lower rates of exposure to community violence (Hypothesis 1). The second hypothesis posits that participation in home-based, after-school activities will be associated with lower rates of exposure to community violence when also accounting for adolescents’ endorsement of familismo both cross-sectionally and over time (Hypothesis 2). The second overall aim of the current study is to determine whether home-, school-, and community-based, after-school activities place adolescents at differential risk for exposure to community violence. The third, specific hypothesis predicts that more frequent participation in school-based activities will be linked to less exposure to community violence concurrently and longitudinally (Hypothesis 3). The final hypothesis proposes that participation in non-structured, community-based activities (as opposed to structured, community-based activities) as well as part-time employment, will be related to higher levels of exposure to community violence cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Hypothesis 4).

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were 416 high school students who were 53% female and had a mean age of 15.5 years (SD = 1.0) at the time of the first survey administration. All of the adolescents included in this sample self-identified as Latino, with 88% identifying as Mexican American and 11% identifying as Puerto Rican. Additionally, in this sample, 85% qualified for free and reduced school lunch, and 84% of the students reported being born in the U.S. The students attended two high schools located in Chicago, IL (54%) and Detroit, MI (46%). Both schools were charter schools serving primarily low-income families and were highly accessible, requiring only a short admission form or entrance in a state-wide lottery system in order to enroll a student. Consequently, the Chicago high school enrolled students from all sections of the city of Chicago. Adolescents from the two schools did not statistically differ from one another on demographic characteristics. According to recent Census data, Latinos have surpassed African Americans as the largest racial/ethnic minority group in Chicago (Serrato 2017). Further, in 2016, the violent crime rate was 1105 per 100,000 residents in Chicago and 2046 per 100,000 residents in Detroit, compared to the national crime rate of 386 per 100,000 people (U.S. Department of Justice 2016).

Procedures

The research team met with students in ninth, tenth, and eleventh grades to explain the purpose of the study, distribute materials, and answer questions. A total of 659 and 437 students in the Chicago and Detroit schools, respectively, attended these recruitment meetings and received recruitment materials to take home and discuss with their parents. Copies of all recruitment materials were provided in both English and Spanish. The recruitment techniques yielded acceptable response rates among low-income, urban populations of high school students (Hammack et al., 2004). Specifically, response rates were 51% in the Chicago high school and 47% in the Detroit high school. Students who returned written parental consent forms were invited to complete a series of measures in an online survey that was administered at school in a group setting. Research team members were present and available to answer questions during every survey administration and all survey administrations were completed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Students received a $25 gift card when they completed the first online survey and a $30 gift card upon completion of the second survey one year later. Administrators at both high schools and the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved all recruitment, data collection procedures, and the survey measures used.

Measures

Adolescents’ age and sex

Four demographic variables were covaried in the analyses: adolescents’ age, adolescents’ sex, maternal education, and adolescents’ gang association. Analyses controlled for adolescents’ age and sex, as both of these demographic characteristics have been associated with exposure to community violence in numerous prior studies. Years in age was utilized for age, and sex was coded as (0) for “males” and (1) for “females”.

Mothers’ education

Mother’s education was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status because students are more likely to be accurate reporters of parental education as opposed to other indicators of social class, like household income. For maternal education, students were asked to report the highest grade in school their mothers had completed and were given a set of responses that included grammar school (grades 1 – 8), some high school, a high school degree or GED, some college, a college degree, or a graduate/professional degree (e.g., law, medicine).

Gang-associated peers

A variable to control for students’ associations with gang members or participation in neighborhood gang activity was also included as a control variable. One question asked students whether they “hang out” with teenagers who are in gangs and was dichotomously coded as (0) for “no” and (1) for “yes”.

Familismo

Familismo, a Latino cultural value prioritizing a sense of family unity, loyalty, support, and commitment, was measured at Time 1 using the Multiphasic Assessment of Cultural Constructs (Gaines et al., 1997). This measure consisted of 10 questions with responses ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. A total score for familismo reflected the mean of these items, with higher scores indicating a stronger endorsement of familismo values. This measure included items such as, “I cherish the time that I spend with my relatives” and “In my opinion, the family is the most important social institution of all”. This measure has demonstrated acceptable internal validity and internal consistency in other studies with Latino samples (Gaines et al., 1997; Guzmán et al., 2005). In the present sample, this scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

After-school activities

Acknowledging that there is no consensus about how best to measure youth’s activity involvement, Bohnert et al. (2010) review highlights four dimensions relevant to measurement: (a) breadth (e.g., number of different activities), (b) intensity (e.g., number of hours spent per week in activities), (c) duration (e.g., total number of years spent in activity), and (d) engagement (e.g., cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement). For the purposes of this study, it is proposed that frequency of involvement in activities will be more related to community violence than other dimensions of activity involvement, like breadth of extracurriculars which are more likely to tap different skills and depth of experiential learning. Frequency of participation, on the other hand, reflects amount of time spent in activities that may keep adolescents away from settings and peers where community violence is likely to happen. Thus, this study extended prior measures of extracurricular activity involvement (Brown & Evans, 2002; Faircloth & Hamm, 2005) and measured frequency of adolescents’ participation in a total of 25 different activities, asking students to report how many times they engaged in each activity on a scale that ranged from (0) “never” to (5) “more than 5 times per week”. The activities were then categorized into 3 different activity types based on their contextual setting: home-based, school-based, or community-based activities.

Frequency of home-based activities consisted of 8 items that included activities like hanging out with family at home, doing chores at home, taking care of younger siblings or older family members at home, hanging out with friends at home, and playing video games at home. A final score consisted of a mean of these items, with higher scores reflecting greater frequency of participation in home-based activities.

Frequency of participation in school-based activities asked students about participating in 7 types of activities related to school, such as organized sports (e.g., school football team), school-based music, art, or theater activities (e.g., school drama club), school clubs or organizations (e.g., student government, robotics club), and getting academic support from a tutor at school. A mean of these items was used to reflect a total score, representing greater participation in school-based activities with higher scores.

Participation in community-based activities asked students to report on the frequency of their participation in 10 different types of activities. These activities were divided into two subscales representing structured and non-structured community-based activities. Structured community-based activities included organized sports (e.g., community basketball team), music or art lessons (e.g., community center art classes), community clubs or organizations (e.g., Boy Scouts), and religious groups or activities (e.g., Bible study group). Non-structured, community-based activities included playing sports with friends outside (e.g., pick-up basketball games), “hanging out” with friends in the neighborhood, attending social events with friends, and driving around in a car with friends. A total mean score for each subscale was created with higher scores reflecting greater frequency of participation in structured and non-structured community-based activities respectively.

Two questions asked students about the frequency with which they engaged in part-time paid work, whether it was a job associated with their school or whether it was not related to their school. These two items were averaged with higher scores reflecting more days per week engaged in part-time employment.

Exposure to community violence

To assess exposure to community violence, the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence, a widely used measure that assess children and adolescent levels of exposure to community violence, was used (Richters & Martinez, 1993). Participants indicated how often they had witnessed and personally experienced violent incidents in the past year, using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from (0) never to (7) 7 or more times. In keeping with the literature in this field, two community violence subscales were constructed: witnessing violence and personal victimization. The witnessing violence subscale consisted of thirteen items that asked students how often they have seen various acts of community violence. An example question was, “How many times have you seen someone else attacked or stabbed with a knife?” The personal victimization subscale consisted of nine items that asked students how often they had been directly and personally victimized by various types of community violence. An example question for this subscale was, “How many times have you yourself been beaten up or mugged?” Responses for each subscale were summed, creating a total score for each subscale with higher scores indicating more frequent witnessing of community violence or victimization by community violence in the year prior to the survey. Since measures of exposure to community violence are indexes that report the frequency of events occurring, as opposed to scales that tap underlying constructs, it is not appropriate to report Cronbach’s alphas as indicators of reliability for the subscales of witnessing violence and personal victimization (Streiner, 2003).

Results

Analytic Strategy

Multiple regression analysis was used to examine cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of exposure to community violence, specifically rates of witnessing violence and personal victimization. All models controlled for adolescents’ age, sex, maternal education, and adolescents’ gang association. Then, adolescents’ familismo endorsement, frequency of home-based after-school activities, frequency of school-based after-school activities, frequency of structured community-based activities, frequency of non-structured community-based activities, and frequency of part-time work were entered as predictors. Longitudinal regression models (based on n = 335) included the same predictors with T1 measures of exposure to violence added to the models. Because the absolute rate of missing data across analyses was relatively small, we used listwise deletion of missing data.

Preliminary Findings

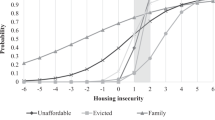

Attrition analyses were conducted to examine whether there were any differences between the adolescents who completed the second survey one year later and the 81 students who did not. No statistically significant differences were found in terms of age, sex, maternal education, gang association, familismo, frequency of home-, school-, structured community-, and non-structured community activities or exposure to violence as either a witness or a victim. Figure 1 depicts adolescents’ frequency of participation in each type of activity included in the home-, school-, and community-based after-school activity groups. Adolescents reported spending the most time in the following activities after school: using social media at home, doing homework or school assignments at home, hanging out with family at home, and doing chores for your family at home. Interestingly, the activities in which adolescents reported spending the most time after school all occurred in their homes. The most frequently endorsed school-based activity was organized sports participation and the most frequently endorsed community-based activities were non-structured activities: hanging out with friends outside your home and playing sports by yourself or with your friends.

As expected, the adolescents in this study experienced high levels of both witnessing community violence and personal victimization. Frequencies for experiencing each type of witnessing violence and personal victimization at least once in the past year are displayed in Table 1. As shown in Table 1 for witnessing violence, more than half (53%) of the adolescents reported seeing someone holding a gun or a knife and 23% of the adolescents had witnessed a shooting. Regarding incidents of personal victimization, almost 25% of the adolescents reported being chased by gangs or individuals who could hurt them and 20% reported being at home when someone had broken into or tried to force their way into their home. Witnessing violence (M = 5.3) was statistically significantly more common than personal victimization (M = 1.7), paired t (400) = 26.3, p < 0.05.

Main Findings

Correlations among all control, independent, and dependent variables included in the models are displayed in Table 2. As predicted in the first hypothesis, correlational findings showed that greater endorsement of familismo values was associated with lower rates of witnessing violence at T1 and T2 and lower rates of personal victimization at T1.

The cross-sectional, multivariate results predicting adolescents’ witnessing of community violence and personal victimization by violence are shown in Table 3. Frequency of home-based, school-based, and structured community-based activities were not statistically significantly associated with witnessing community violence or victimization by violence concurrently. Thus, the second hypothesis that home-based activities would be associated with lower rates of exposure to community violence when accounting for familismo values and the third hypotheses that greater school-based activity participation would also be associated with less exposure to community violence were not supported by these findings. Also as displayed in Table 3, frequency of non-structured community-based activities (b = 0.21, p = 0.00002; b = 0.09, p = 0.001) and frequency of part-time work (b = 0.39, p = 0.04; b = 0.38, p = 0.001) were cross-sectionally associated with statistically significantly higher rates of both witnessing violence and personal victimization, respectively. These results support the fourth hypothesis that non-structured community-based activities and part-time employment would be associated with greater exposure to community violence cross-sectionally. Additionally, associating with adolescents who are in gangs (b = 2.9, p < 0.0001; b = 1.4, p < 0.0001) was statistically significantly associated with greater reports of witnessing community violence and being personally victimized by violence concurrently. Adolescents who reported associating with peers who are in gangs reported witnessing about 3 more violent events in the past year compared to those who did not. Finally, familismo (b = −0.38, p = 0.004) and female sex (b = −0.64, p = 0.002) were associated with statistically significantly lower rates of personal victimization, but not with witnessing violence, when other covariates were statistically controlled.

The longitudinal results displayed in Table 4 reveal that exposure to community violence at T1 was strongly associated with exposure to community violence one year later at T2. When controlling for T1 exposure to community violence, frequency of non-structured community-based activities predicted statistically significant increases in witnessing community violence (b = 0.11, p = 0.04) and personal victimization (b = 0.08, p = 0.04) over time. These findings also support the fourth hypothesis, predicting that participation in non-structured community-based activities would be longitudinally related to higher levels of adolescents’ exposure to community violence. In addition, female sex was associated with statistically significant decreases in rates of personal victimization over time (b = −0.52, p = 0.04) when other covariates were statistically controlled. Familismo and frequency of home-based, school-based, structured community-based, and part-time employment at T1 were not significantly associated with T2 witnessing violence or victimization by violence.

Discussion

Exposure to community violence and the sequalae of deleterious behavioral and psychological consequences experienced by children and adolescents presents a serious, on-going public health crisis. While certain demographic characteristics, such as being a racial/ethnic minority youth or a member of a low-income family, have been associated with increased rates of exposure to community violence, the present study examines how more malleable environmental and cultural factors may increase or decrease adolescents’ exposure to community violence. Specifically, this study examines whether participation in different types of after-school activities and endorsement of familismo, a widely held Latino cultural value, are associated with Latino adolescents’ exposure to community violence concurrently and over time. Since Latino adolescents and youth from low-income families participate in less structured, organized activities, compared to European American adolescents and youth from higher income families, this study comprehensively assesses adolescents’ after-school activities by incorporating home-based and school-based activities as well as distinguishing between structured and non-structured community-based activities. Moreover, this study directly examines the proposition that past studies have found a link between familismo and lower rates of adolescents’ exposure to community violence because familismo reflects adolescents’ decisions to spend more time in home-based settings, away from neighborhood dangers.

Among the current sample of Latino youth residing in Chicago and Detroit neighborhoods, adolescents reported remarkably high rates of exposure to community violence, as both witnesses and victims of violence. Consistent with prior research (Menard & Huizinga, 2001; Selner-O’Hagan et al., 1998), Latino adolescent boys reported higher rates of personal victimization compared to Latina adolescent girls. The current findings highlight the importance of continued efforts to diminish exposure to community violence among urban youth. By identifying after-school activities that increase or reduce adolescents’ risk for exposure to community violence, the results from this study can help inform after-school programming for racial/ethnic minority youth living in poor, urban neighborhoods.

In general, extracurricular activity participation is associated with a host of positive developmental outcomes (Farb & Matjasko, 2012; Haghighat & Knifsend, 2019; Mahoney et al., 2006); however, as previously mentioned, low-income, urban youth spend significantly less time in extracurricular activities compared to their higher socioeconomic and suburban counterparts (Pedersen & Seidman, 2005). On a practical level, under-resourced schools and impoverished communities may simply not have a large selection of after-school activity options. Indeed, the present sample of Latino adolescents most frequently reported spending their after-school hours at home, engaged in activities like using social media, doing chores, and taking care of other family members. Difficulties with costs, transportation, and scheduling may also restrict adolescents’ extracurricular participation. Certain community-based activities may be the most viable option for some adolescents. Nevertheless, community-based activities vary greatly by the type of structure and supervision provided, and many adolescents may, instead, be obliged to or voluntarily decide to engage in activities and responsibilities at home.

In keeping with the first hypothesis, correlational findings indicated that greater endorsement of familismo, reflecting family obligations and responsibilities, was associated with lower rates of witnessing and being personally victimized by community violence concurrently. Additionally, endorsement of familismo had a bivariate association with lower rates of witnessing violence one year later. However, the results did not support the second hypothesis that when accounting for both familismo values and home-based activities, it would be home-based activities, rather than familismo, that would be associated with less exposure to community violence. In a prior study, greater endorsement of familismo was associated with lower rates of witnessing violence and victimization (Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013). Although familismo and participation in home-based activities were positively related to each other, only familismo, not home-based activities, was associated with exposure to community violence in the current study. Greater endorsement of familismo was related to less personal victimization cross-sectionally, but not one year later when also accounting for prior exposure to community violence. These results suggest that familismo may have a unique protective role in reducing exposure to community violence among adolescents that is not solely attributed to a higher frequency of participating in after-school activities within safer home-based settings.

In the context of high-crime, urban neighborhoods, the expectation that familismo will not be significantly associated with exposure to community violence when home-based activities are accounted for was not supported. One must then ask, “What may explain the protective effect of familismo after accounting for adolescents’ involvement in home-based activities?” Endorsement of familismo values may reduce exposure to community violence by influencing the manner in which youth engage in after-school activities. In other words, familismo may represent greater parental monitoring and supervision of adolescent activities in general. A hallmark of adolescence in the U.S. is the desire for greater autonomy and engagement with peers. It may be that for Latino youth in poor neighborhoods, familismo reflects a culturally appropriate way in which adolescents and their families balance adolescent needs for autonomy and activities with peers while still allowing for protective monitoring and supervision by adults. Further, familismo may reflect strong, positive relational dynamics, such as open communication, closeness, and trust, between adolescents and parents, allowing adolescents to comfortably heed parental advice about neighborhood safety and cautions. Certainly, more research is needed to investigate and understand the protective effects of both familismo values and behavior among Latino youth and families.

Addressing the third hypothesis, frequency of adolescents’ participation in school-based activities and structured, community-based activities were not associated with exposure to community violence, highlighting the importance of assessing the specific characteristics associated with different kinds of activities when evaluating their impact. In another study of Latino youth, participation in school sports and school clubs was similarly not associated with exposure to community violence (Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013). School-based activities and structured community-based activities may share certain qualities, namely the presence of adult supervision, a well-organized structure for participation, and the lack of time for unstructured socializing with peers. For youth in dangerous neighborhoods, these activity characteristics may accentuate the positive influences of after-school activity involvement while not increasing youth’s exposure to community violence.

The final hypothesis was supported with findings of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between frequency of participation in non-structured community-based activities and higher rates of both witnessing violence and being victimized by violence. Non-structured activities and socializing with peers may increase adolescents’ exposure to community violence in several ways. For instance, these activities may occur in risky neighborhood settings and activities like, “hanging out” with peers, are also likely to occur with little adult supervision. In this way, it may be the location or the characteristics of these activities, specifically their lack of structure and supervision, that link non-structured, community-based activities with greater exposure to community violence among adolescents. These findings are in accord with prior results found among both Latino and African American youth (Antunes & Ahlin, 2018; Kennedy & Ceballo, 2013; Richards et al., 2004). Furthermore, these longitudinal results suggest it is unlikely that these findings are driven by highly violence-exposed adolescents seeking out community-based activities as safe havens, since greater activity involvement preceded increases in exposure to community violence. The frequency of part-time employment was associated with greater rates of witnessing violence and being victimized by violence cross-sectionally, but not longitudinally. Adolescents who hold part-time jobs likely spend more time traveling to and from employment sites in the evening hours when violence is more likely to happen. Additionally, earning money may make employed adolescents the targets of neighborhood crime.

The findings demonstrate that specific types of community-based activities do matter, and they matter over time. Non-structured community-based activities, for example “hanging out” with friends or playing pick-up sports games, were associated with higher rates of witnessing violence and personal victimization both concurrently and one year later. Prior exposure to violence and frequency of participation in non-structured, community-based activities were the only predictors associated with both witnessing violence and experiencing victimization by violence one year later. Still, some youth may avoid participation in community-based activities altogether because of the risk of exposure to community violence. In qualitative interviews with Latino adolescents, Camacho-Thompson and Vargas (2018) found that girls’ fear of sexual harassment and boys’ concerns about gang intimidation were deterrents to participating in structured community-based activities. In order to become involved in certain community activities, these adolescents reported that they would have to travel on streets known for the threats posed by male harassers and gang members. Adolescents knew that, at their worst, these risks could be quite severe and could include rape for adolescent girls or serious physical assault by gang members for adolescent boys. In addition to specific activity characteristics then, neighborhood safety may impact the types of activities that adolescents are willing to seek out and feel that they can safely engage in (Bohnert et al., 2009).

While participation in extracurricular activities is associated with numerous positive developmental outcomes, some types of after-school activities place adolescents at greater risk for exposure to community violence. This study helps identify characteristics of after-school activities associated with more or less risk of exposure to community violence for Latino youth and supports the development of structured, well-supervised activities in poor, high-crime neighborhoods. Although financial budget constraints often lead to cutting extracurricular opportunities for youth, the present results add to the growing base of evidence against such measures. The trend towards privatized, pay-to-play activities for only a small number of select youth is short-sighted, as it obstructs the developmental growth and potential of all youth. Structured school- or community-based extracurricular activities should be equitably available for all students in U.S. schools so that adolescents are discouraged from engaging in non-structured community activities (Meier et al., 2018). Indeed, some evidence suggests that participation in structured extracurricular activities is more strongly linked to positive developmental outcomes for youth from low-income families (Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Meier et al., 2018; Morris 2015).

It is important to note that adolescents’ after-school activity participation is a dynamic phenomenon, changing by years, seasons, weeks and even days of the week. Survey methods capture only a snapshot of activity participation for adolescents reporting on the past academic year. Indeed, few studies are able to tap the truly dynamic changes in adolescents’ activity participation over long durations of time. Another limitation in the current study is the possible role of self-selection effects in adolescents’ after-school activity participation. Unmeasured factors may influence the activities in which adolescents choose to spend their after-school hours. Additionally, the current findings are based on a sample of primarily Mexican American and Puerto Rican adolescents residing in mid-western cities and may not generalize to other Latino adolescents in the U.S. Finally, the measures used in this study were all based on youth self-report without access to multiple informants.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to knowledge about the relations between how adolescents spend their after-school time and exposure to violence in their communities. The results highlight the link between non-structured after-school activities and exposure to community violence both concurrently and longitudinally. Most importantly, adolescent activity participation is highly flexible and amenable to change; thus, discouraging participation in non-structured community-based activities and providing adolescents with options for structured, well-supervised after-school activities will help lessen exposure to community violence and the negative psychological symptoms associated with community violence. Of note, familismo was concurrently associated with less exposure to community violence, and thus closer examination of the mechanisms by which endorsement of familismo values lessens youth’s exposure to community violence is warranted in future studies.

Conclusion

Adolescents’ exposure to high and chronic rates of community violence presents a pressing public health crisis. Identifying malleable factors that increase or decrease adolescents’ risk for exposure to community violence remains a significant gap in our knowledge base. In addressing this gap, the current study investigated endorsement of the Latino cultural value of familismo and participation in three types of after-school activities as precursors of exposure to community violence among a sample of urban, Latino adolescents. Whereas endorsement of familismo was associated with lower rates of personal victimization cross-sectionally, frequency of non-structured community-based activities and part-time work were associated with higher rates of witnessing community violence and being personally victimized by violence concurrently. While controlling for prior exposure to community violence, frequency of non-structured community-based activities was related to witnessing more community violence and greater victimization one year later. The present findings underscore the importance of providing structured, well supervised after-school activities for low-income adolescents in high-risk neighborhoods.

References

Antunes, M. J. L., & Ahlin, E. M. (2018). Minority and immigrant youth exposure to community violence: The differential effects of family management and peers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, X, 1–30.

Bohnert, A. M., Fredricks, J., & Randall, E. (2010). Capturing unique dimensions of youth organized activity involvement: theoretical and methodological considerations. Review of Educational Research, 80(4), 576–610.

Bohnert, A. M., Richards, M., Kohl, K., & Randall, E. (2009). Relationships between discretionary time activities, emotional experiences, delinquency and depressive symptoms among urban African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 587–601.

Bohnert, A. M., Richards, M. H., Kolmodin, K. E., & Lakin, B. L. (2008). Young urban African American adolescents’ experience of discretionary time activities. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18(3), 517–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00569.x.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742.

Brown, R., & Evans, W. P. (2002). Extracurricular activity and ethnicity creating greater school connection among diverse student populations. Urban Education, 37(1), 41–58.

Calzada, E. J., Fernandez, Y., & Cortes, D. E. (2010). Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 77–86.

Camacho-Thompson, D. E., & Vargas, R. (2018). Organized community activity participation and the dynamic roles of neighborhood violence and gender among Latino adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62, 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12267.

Cicchetti, D., & Lynch, M. (1993). Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry, 56, 96–118.

Cooley-Strickland, M., Quille, T. J., Griffin, R. S., Stuart, E. A., Bradshaw, C. P., & Furr-Holden, D. (2009). Community violence and youth: affect, behavior, substance use, and academics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(2), 127–156.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. (2007). Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2006 (U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-233). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Faircloth, B. S., & Hamm, J. V. (2005). Sense of belonging among high school students representing 4 ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(4), 293–309.

Farb, A. F., & Matjasko, J. L. (2012). Recent advances in research on school-based extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Developmental Review, 32(1), 1–48.

Fowler, P. J., Tompsett, C. J., Braciszewski, J. M., Jacques-Tiura, A. J., & Baltes, B. B. (2009). Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 227–259.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relationships. Developmental Psychology, 42, 698–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.698.

Fredricks, J. A. & Simpkins, S. D.(2012).Promoting positive youth development through organized after-school activities: taking a closer look at participation of ethnic minority youth.Child Development Perspectives, 6, 280–287.

Gaines, S. O., Marelich, W. D., Bledsoe, K. L., Steers, W. N., Henderson, M. C., & Granrose, C. S., et al. (1997). Links between race/ethnicity and cultural values as mediated by racial/ethnic identity and moderated by gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1460–1476.

Gibson, C. L., Morris, S. Z., & Beaver, K. M. (2009). Secondary exposure to violence during childhood and adolescence: does neighborhood context matter? Justice Quarterly, 26, 30–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820802119968.

Goldner, J., Peters, T. L., Richards, M. H., & Pearce, S. (2011). Exposure to community violence and protective and risky contexts among low income urban African American adolescents: a prospective study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 174–186.

Guzmán, M. R., Santiago-Rivera, A. L., & Hasse, R. F. (2005). Understanding academic attitudes and achievement in Mexican-origin youths: ethnic identity, other-group orientation, and fatalism. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.3.

Haghighat, M. D., & Knifsend, C. A. (2019). The longitudinal influence of 10th grade extracurricular activity involvement: implications for 12th grade academic practice and future educational attainment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 609–619.

Halgunseth, L. C., Ispa, J. M., & Rudy, D. (2006). Parental control in Latino families: an integrated review of the literature. Child Development, 77, 1282–1297.

Hammack, P. L., Richards, M. H., Luo, Z., Edlynn, E. S., & Roy, K. (2004). Social support factors as moderators of community violence exposure among inner-city African American young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(3), 450–462.

Hardaway, C. R., McLoyd, V. C., & Wood, D. (2012). Exposure to violence and socioemotional adjustment in low-income youth: an examination of protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 112–126.

Kennedy, T. M., & Ceballo, R. (2013). Latino adolescents’ community violence exposure: after-school activities and familismo as risk and protective factors. Social Development, 22(4), 663–682.

Leavell, A. S., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Ruble, D. N., Zosuls, K. M., & Cabrera, N. J. (2012). African American, White and Latino fathers’ activities with their sons and daughters in early childhood. Sex Roles, 66, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0080-8.

Mahoney, J. L., Harris, A. L., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Organized activity participation, positive youth development, and the over-scheduling hypothesis. Social Policy Report, 20, 3–31.

Mahoney, J. L., & Stattin, H. (2000). Leisure activities and adolescent antisocial behavior: the role of structure and social context. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0302.

Meier, A., Hartmann, B. S., & Larson, R. (2018). A quarter century of participation in school-based extracurricular activities: Inequalities by race, class, gender, and age? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1299–1316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0838-1.

Menard, S., & Huizinga, D. (2001). Repeat victimization in a high-risk neighborhood sample of adolescents. Youth & Society, 32, 447–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X01032004003.

Morris, D. S. (2015). Actively closing the gap? Social class, organized activities, and academic achievement in high school. Youth & Society, 47(2), 267–290.

Neely, S. R., & Vaquera, E. (2017). Making it count: breadth and intensity of extracurricular engagement and high school dropout. Sociological Perspectives, 60(6), 1039–1062.

Newman, S. A., Fox, J. A., Flynn, E. A. & Chriteson, W. (2003). America’s afterschool choice: juvenile crime or safe learning time. Washington, DC: Fight Crime Invest in Kids. http://www.fightcrime.org./sites/default/files/reports/asTwoPager%2010:27:03.pdf.

Pedersen, S., & Seidman, E. (2005). Contexts and correlates of out-of-school activity participation among low-income urban adolescents. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson & J. S. Eccles (eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs (pp. 85–109). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Peterson, R. D., Krivo, L. J., & Harris, M. A. (2000). Disadvantage and neighborhood violent crime: do local institutions matter? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 37(1), 31–63.

Richards, M. H., Romero, E., Zakaryan, A., Carey, D., Deane, K., Quimby, D., Patel, N., & Burns, M. (2015). Assessing urban African American youths’ exposure to community violence through a daily sampling method. Psychology of Violence, 5(3), 275–284.

Richards, M. H., Larson, R., Miller, B. V., Luo, Z., Sims, B., Parrella, D. P., & McCauley, C. (2004). Risky and protective contexts and exposure to violence in urban African American young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_13.

Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P. (1993). The NIMH community violence project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry, 56, 7–21.

Selner-O’Hagan, M. B., Kindlon, D. J., Buka, S. L., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. J. (1998). Assessing exposure to violence in urban youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002196309700187X.

Serrato, J. (2017). Mexicans and ‘Hispanics,’ now the largest Minority in Chicago. Chicago Tribune, http://www.chicagotribune.com/hoy/ct-mexicans-and-hispanics-largest-minority-in-chicago-20171013-story.html.

Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S., Rhodes, H. J., & Vestal, K. D. (2003). Prevalence of child and adolescent exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(4), 247–264.

Streiner, D. L. (2003). Being inconsistent about consistency: when coefficient alpha does and doesn’t matter. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80, 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8003_01.

U.S. Department of Justice (2016). Uniform Crime Report: Crime in the United States, 2016. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/topic-pages/tables/table.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all of the students who made time to participate in this study and the school administrators who made the students’ participation possible. In addition, we thank all members of the Resilience in Context lab at the University of Michigan for their work and support.

Authors’ Contributions

R.C. conceived of and coordinated the study as well as drafted the manuscript; J.A.C. participated in the design of the study, conducted the statistical analysis, and helped draft the manuscript; F.A. participated in the design and coordination of the study; R.M.J. participated in the design and coordination of the study; T.M.K. helped conceive the study and participated in the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation (grant no. 1348957) awarded to the first and second authors.

Data Sharing and Declaration

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Michigan and performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All participating students under 18 years of age provided signed parental consent forms and completed adolescent assent forms. Students who were 18 years old or older completed consent forms. School administrators at each school approved of all recruitment materials, survey measures, and data collection procedures.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ceballo, R., Cranford, J.A., Alers-Rojas, F. et al. What Happens After School? Linking Latino Adolescents’ Activities and Exposure to Community Violence. J Youth Adolescence 50, 2007–2020 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01480-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01480-6