Abstract

This paper aims to describe how healthcare providers perceived spirituality and spiritual care while caring for dying patients and their families in a hospice setting in Karachi, Pakistan. Using a qualitative interpretive description design, individual in-depth interviews were conducted among healthcare providers. Thematic analysis approach was used for data analysis. Spirituality and spiritual care were perceived as shared human connections, relating to each other, acts of compassion, showing mutual respect while maintaining dignity in care and empowering patients and families. Developing spiritual competency, self-awareness, training and education, and self-care strategies for healthcare providers are essential components promoting spiritual care in a hospice setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

End-of-life (EOL) care often brings various spiritual and existential issues and concerns for dying patients and their caregivers. During these difficult times, patients and families look for compassionate care and support from healthcare providers (HCPs) (Dedeli et al., 2015; Ross & Austin, 2015; Skalla et al., 2013). Spiritual care involves caring for the whole person, physically, emotionally, socially, and spiritually (Puchalski, 2013). The diagnosis of chronic or a life-threatening illness may trigger spiritual struggles for patients and families, whether or not they are religious and result in experiencing spiritual distress or spiritual suffering—an inability to connect with what gives them meanings in their lives (Jacobs, 2019). Evidence suggests that spirituality eases the suffering and provides meaning to patients and families in their dying experiences (Koper et al., 2019). Spirituality has been found to be a source of comfort, peace, strength, and coping for both patients and families at the EOL. Healthcare professionals can ease the spiritual sufferings by attending to spiritual needs and provision of spiritual care at EOL. Spirituality helps patients and families transcend their sufferings during end of life (Bernard et al., 2014; Lalani et al., 2019; Paiva et al., 2015), promotes healing, endures pain, and improves quality of life of both patients and families in the hospice setting (O’Brien, et al., 2019).

Spirituality and spiritual care are at the core of hospice and palliative care philosophy (El Nawawi et al., 2012). Current hospice care guidelines also encourage HCPs to integrate spirituality and spiritual care for their patients and families at EOL. While spiritual care is a core element of hospice and palliative care, it remains unclear how this care is perceived and delivered by HCPs at the EOL (McSherry & Jamieson, 2013). Patients and families at EOL often identify that their spiritual needs are not adequately met and that spirituality is not discussed with them as openly as they wish (Richardson, 2014). Several studies have identified that healthcare providers often remain uncomfortable identifying the spiritual needs of patients and families during end of life. Organizational factors such as heavy workload, low staffing, time constraints, lack of training, and resources often impede the ability of healthcare providers to look after their patients and family caregivers’ spiritual needs and preferences (Lalani & Chen, 2021; Koper et al., 2019). Additionally, personal factors such as lack of priority from spirituality and spiritual concerns or perceiving a patient’s spirituality as a personal matter and cultural factors such as religious discordance impede provision of spiritual care (Koper et al., 2019). Evidence supports that HCPs own understanding of spirituality influences how they perceive spiritual needs and provide spiritual care to their patients while providing EOL care (Attard et al., 2019; McSherry & Jamieson, 2013). HCPs should have at least basic language to assess and address the spiritual needs of a patient, especially at the EOL when spiritual needs are the greatest (Richardson, 2014). However, seemingly there are very few studies that determine what nurses and other HCPs perceive spirituality to be and how spiritual care should be provided during EOL care in a hospice setting. A limited understanding and knowledge gap also exist around how spiritual care needs and preferences are perceived across different cultures. This paper aims to describe how HCPs perceived spirituality and spiritual care while providing EOL care to dying patients and their families in a hospice setting.

Study Context

The study was conducted in a single 45-bed charitable cancer hospice setting in Karachi, Pakistan. Pakistan is a developing, low-resourced country with a population of 216 million (worldbank.org, 2019). Majority of the people in Pakistan are Muslims. 24.3% people live below poverty line, and the death rate is 7.1/1000 population (worldbank.org, 2019). The leading causes of death include non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer. The concept of hospice care is not well established in Pakistan, and most of the end-of-life care is provided in acute care hospitals or at home. At the time of data collection, there was only one hospice in Karachi, Pakistan, a city with a population of 16 million (World population review, 2020). The hospice is a charitable non-profit and aims to provide services to patients and families who are poor and in need of welfare to support the healthcare cost of their dying loved ones. Patients who are suffering from terminal stages of cancer and are expected to die within six months of their advanced illness are admitted in the hospice. The hospice viewed as a last resort of care and comfort for impoverished families, they receive food and medications for the patient and their family members during the stay in the hospice. Some do not reside in the city where the hospice is located and had to travel long distances to reach the hospice. In some cases, family caregivers had quit their jobs and were staying at their relative’s homes to take care of their dying patients in the hospice. The nurse-to-patient ratio in the hospice is 1:20. Most physical and hygiene care in the hospice setting is provided by family caregivers. As per hospice visitor policy, females were not allowed to stay in the hospice with their dying spouse during the night hours due to cultural reasons and thus suffered additional struggles with giving care. A small prayer room in the hospice was a source of peace and comfort for the families in the hospice setting.

Methodology

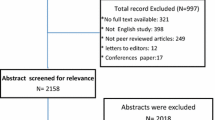

A larger study was conducted to describe the experiences of spirituality and spiritual care and how spirituality shapes caregiving practices of family caregivers who are caring for their terminally ill family member in a hospice setting in Pakistan. To explore the complex phenomena of spirituality among caregivers, an interpretive descriptive (ID) design, a qualitative research approach was used. ID design allows contextual and experiential knowledge of the complex phenomena in this case about spirituality and spiritual care and assists in finding applicable realistic solutions to improve EOL care practices in hospice settings (Thorne, 2016). The qualitative study included 34 individual interviews with family caregivers (n = 18) and HCPs (n = 6) in a single hospice setting located in Karachi, Pakistan (Lalani et al., 2019). HCPs were included in the study to supplement the data gathered from the primary study participants who were the family caregivers. ID design encourages the use of triangulation and supplementation of data with different sources as it brings richness and clarity in the data and thus allows a deeper understanding of the concepts under study. Additionally, triangulation minimizes bias and enhances the validity and reliability of the study findings (Thorne, 2016). This paper reports the qualitative findings from the HCPs in the larger study. Data obtained from the family caregivers are published earlier in Lalani, et al., 2019. This study received ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board and operational approval from the hospice where the actual study was conducted.

Sample and Data Collection

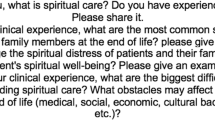

Findings in this paper include data obtained from HCPs in the larger study. A purposive sample of HCPs including doctors and nurses who had worked in the hospice setting for at least one year could read, write, and speak English or Urdu and were willing to share their experiences with the researcher. For recruitment purposes, an information letter was sent to each hospice staff to determine who wished to participate in the study and flyers about the study were posted in the hospice setting. Those interested in participating in the study contacted the researcher. Data included six individual in-depth interviews. An interview guide (see Table 1) was developed by the researchers. Each interview was 50 min to one hour in length. During the interviews, participants were asked about how they perceive spirituality and spiritual care while caring for the dying patients and their families in the hospice setting followed by other questions in the interview guide. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant before the interviews, and verbal consent was again sought at the time of each interview. Interviews were held in a separate conference room located in the hospice and at a time mutually convenient and agreed between the researcher and the participant. As the primary language of the participants was Urdu, all the interviews were obtained in Urdu. All the interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed in Urdu language, and then translated into English. A permission letter was obtained from the hospice setting in Karachi, whereas ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics review board at the University of Alberta, Canada.

Data Analysis

Interpretive description offered an inductive approach toward understanding the phenomena of spirituality and spiritual care. The data analysis process involved inductive reasoning, constant engagement, testing, challenging preliminary interpretations, and, finally, conceptualizing to understand the phenomenon (Thorne, 2016). A thematic analytic approach was used for data analysis (Thorne, 2016). Soon after the second interview, data transcription and translation began. A parallel translation approach was used for the data (Santos et al., 2015). Upon completion of transcription and translation, repeated immersions in the data occurred in order to analyze for emerging categories, linkages, and patterns in the data. A quotable quotes file was developed based on different categories, linkages, and patterns in the data, reflective notes were added in the data, and further literature was sought to see any new emerging patterns and themes in the data. A final thematic list was developed and was then shared and discussed with the research team to build consensus over the findings. Trustworthiness and credibility were maintained in the study through constant engagement with the data, and by maintaining an audit trail of all the methodological and analytic decisions made during the study. A separate log of all activities was kept including memos and process notes, a reflexive journal, and regular consultation and meetings with the research team.

Findings

Findings include participants’ demographic information as shown in Table 2. Several themes found under the study include spirituality as a sense of humanity, sense of attachment and belongingness, providing compassionate care, showing dignity and treating the individual as a “person,” respecting cultural and religious beliefs, and spiritual care strategies.

Spirituality as a Sense of Humanity (for the Sake of Humanity)

Nearly all participants referred to spirituality as a complex and broader concept than religion saying, “spirituality is a complex phenomenon not simple,” “religion is simply my faith,” “spirituality is bigger than religion,” “it is a way of life,” “an important aspect of humanity,” “a universal human experience that connects us all and provides us sense of strength, internal peace, happiness, and satisfaction.” Participants used different words and phrases while describing the term spirituality such as “the love, affection, and care we demonstrate to our patients,” “to serve humankind,” “caring for others,” “expression of my own inner self,” and “something for the sake of humanity (insaniat ke naate).” Spirituality was perceived as serving humanity or doing something for the sake of humanity combined with a collective sense of social connectedness or togetherness. Spirituality was perceived as an essence of humanity that requires us to keep welfare of the whole of mankind above our own personal needs. As one of the participants said:

Spirituality is something related to human and humankind. Religion is separate. Like when we care for patients, we don’t think about their religion. We treat every patient equally whatever religion they belong to. People with different religion comes here. Our religion ‘Islam’ teaches us to treat/care every human uniquely, fairly and equally without any discrimination of any religion. (Participant 2)

They have become so close and attached to me. If I don’t go for two days, they will still wait and don’t allow anyone else to do his wound care and dressing. It gives me a lot of eternal happiness. I feel like at least I could do something for this patient, something for the sake of humanity (insaniat ke naate). (Participant 1)

To me what is spirituality, it’s a difficult question. Something, which is closer to our heart, mind, it’s like doing good for others. Whatever you do, whatever field you are in, I should not hurt others, this gives me internal peace. This is something I call spirituality.

HCPs viewed spirituality as about bringing passion, bringing ones’ heart, soul, and spirit to their caregiving practices. For HCPs, the caregiving practices provided a deep sense of meaning and served a higher purpose. Findings also indicate that all the participants were Muslims. As per religious teachings of Islam, caring for the dying individual is a blessed task. Enduring faith and religious beliefs were valued, and such values served as guiding principles in their caring practices. Furthermore, it is interesting to note in the findings that although participants did not have any formal education in terms of spiritual care and spirituality, some clarity did exist among them around the concepts of religion, spirituality, and spiritual care. It can be assumed that such knowledge and values of caring may have emanated from their own personal and professional experiences, or from their own religious values and beliefs.

Sense of Attachment and Belongingness

For most participants, spirituality and spiritual care meant developing a sense of belongingness, connectedness, and attachment with the patients and families they were caring for. One of the participants said: “It was a natural feeling. I just felt a closeness/attachment, a kind of connectedness with him (patient).” Another participant added:

Yeah, there was a patient, he had come with cancer or the colon. The couple was newly married. Soon he just became like family to us in the hospice setting. I don’t remember his name. Whenever he would speak to us, we felt like he is someone related to us. Whenever he will come and greet us, it feels like he is a brother to me. They stayed here for a year and he died here. (Participant 3)

Participants truly believed that their simple acts of caring such as holding hands, a touch, or a gentle massage can generate a feeling of connectedness while caring for patients and families. A strong sense of attachment and connectedness represents our spiritual needs, humanistic values and our shared spirituality in our day to day lives. As one participant added:

To be sweet with mankind, behave properly and communicate nicely. If nothing much, at least we can give a smile to them or talk to them in a nice and kind manner. This is really encouraging…. (Participant 5)

Initially I used to think that it would be very difficult for me to work here but with time I developed a high sense of attachment with this place. Now even on my holidays, I keep thinking about this place, the patients and their families… somehow this place has become a part of me and feels like a family. (Participant 6)

Along with the sense of attachment, participants also valued providing compassionate care during EOL and formed another theme under the study.

Providing Compassionate Care

For participants, being compassionate meant helping the patients and families cope with their loss, grief, and suffering. HCPs felt that they needed to demonstrate extra supportive care acts, show presence, and offer a listening ear to ease the suffering of the patients and their families in the hospice setting. As one participant said:

You know that the patients and families who come here are already under stress and are worried… We must treat them as humans and respect them. If the doctor is gentle in his behavior and listening, it can cure half of the illness. We must try to be gentle with our patients. It will provide them peace and comfort…We try to provide good care so that they can cope better and experience minimum pain and suffering (takleef kam se kam ho jaaye). (Participant 4)

The dying experience is often associated with fear, denial, and anxiety for patients and families in a hospice setting. HCPs strongly felt the need to understand patient and family concerns, needs, and preferences during EOL care. Participants expressed that near-death experiences often change the care needs of the dying person and add to the complexities around caregiving. The impoverished and disadvantaged patients and families need extra support and compassionate care at the EOL. In times of suffering, spiritual issues often become the central concern and therefore should be the focus of care. Compassionate care might help the individuals to transcend their difficulties and sufferings and may aid in personal growth and self-transformation.

…Whatever time they (patients) are left with, we must make sure that they get good quality of life. We try to keep them content and blissful. We behave well with them, sit with them, and talk. Since we cannot increase their quantity of life, we can at least improve their quality of life… (Participant 3)

Participants strongly supported the idea that a compassionate and loving environment can facilitate a sense of wholeness, acceptance, and hope and enhance spiritual life of patients and families at the EOL. Along with compassion, dignity was found as another theme under the study.

Showing Dignity and Treating the Individual as a “Person”

All the participants talked about the importance of maintaining dignity of patients and their families at the EOL care and considered it as an essential aspect of one’s spiritual well-being. HCPs promoted dignity by creating mutual trust, respect, and honor, by maintaining privacy and autonomy, and by empowering patients and their families in making healthcare choices and treatment decisions at the EOL care. For example, one of the participants said:

Our patients are poor and less educated… they do not have a lot of guidance. So, no matter how many times they ask me a question, I try to respond to their questions every time in a polite manner. (Participant 1)

Another participant added:

We should not discriminate against our patients based on their cultural or religious ideas, beliefs and values. We need to respect their values and beliefs. This is very important. whatever their religion, race, creed or language, we need to respect them. As a result, we will also get respect in return. Also, we should not ridicule our patients on a financial basis. Whether they are giving money or not, they know or the hospice administration knows, but whatever …we get paid and it is our responsibility to provide good care without any discrimination. (Participant 3)

Participants strongly believed that dignity involved a feeling of self-worth, and demands respectful, indiscriminate, and empathic communication toward patients and families. Dignity was a value and a culturally laden concept and was often influenced by religious and cultural norms and values that one identifies with EOL care. The ethics of care followed cultural and religious norms and beliefs, and respecting these values and beliefs was another theme in the study.

Respecting Cultural and Religious Values

Most participants affirmed that EOL care was influenced by various cultural and religious values and beliefs and that such values must be respected during care. Such care promoted a sense of self-worth, dignity among patients as described earlier, and empowers them as individuals to make their own choices and decisions in care. Participants expressed the fear that failure to do so may result in mistrust, despair, and diminished quality of life at EOL care. HCPs shared various religious rituals and practices that patients and families prefer during EOL care such as performing special prayers, Quran recitation, and use of religious amulets. These practices were believed to relieve suffering during illness and dying and provide additional strength, peace, and comfort to patients and their families in the hospice setting.

We must not stop family caregivers if they want to perform any special prayers or any religious rituals for their dying family member… we need to respect their values. We allow if they wish to bring a religious scholar into the hospice. We should allow them to offer their prayers. We should facilitate families in their beliefs and practices… The Quran Sharif [holy book], Sura Yasin, Punj sura [Holy Scriptures], jaye-namaz [a special cloth that Muslims use while praying], rosaries, all these things are available here in the hospice. (Participant 2)

Sometimes patients don’t feel comfortable reciting their prayers (Namaz) when they are receiving chemotherapy. we can explain to them that they can recite their prayers with chemotherapy, it’s not a limitation. They can recite their prayers on the bed too. Our religion provides us this flexibility. So, they feel calm and then they listen to us. And they feel satisfied.

Similarly, HCPs also iterated that there were certain rituals/practices which can be harmful to the patient. For example, one of the HCPs stated that some patients wanted to keep a long beard as part of religious tradition and some wanted to wear a religious amulet around their neck along with the tracheostomy; such practices were considered as harmful because they may lead to infections. Participants recommended that in such situations, staff must act wisely and demonstrate respect for the patient/family values and beliefs.

You know there are some patients on tracheostomy and families put things around their neck (like a necklace) which are religious to them and won’t allow us to remove them. Then we need to explain to them clearly that it can cause infections. Some families listen and understand, some don’t. (Participant 4)

There was one patient. He had this long beard which was a kind of religious to him (you know keeping long beard is Sunnat in Islam). He had a wound around his cheek and neck. The hair from the beard was coming in the wound and was a source of infection. We explained to him that he can shorten his beard, but he was reluctant and the family was also unable to convince the patient. So, at last I told the family that they can consult a religious scholar and explained to him the pros and cons of keeping the beard with the wound. The strategy worked, and he agreed to shave his beard. Now he and his family both are happy and satisfied. Yesterday when I did his dressing, he was so happy and continues giving me lots of prayers. I also felt internally happy, peaceful, and satisfied. (Participant 6)

Prayers and counseling with a religious scholar were commonly practiced among the patients and families in the setting as it provided them comfort, peace, and increased strength in coping during loss. While discussing religious and cultural practices during EOL life care, staff also talked about several spiritual care strategies provided to patients and families in the hospice setting and these became another theme in the study.

Spiritual Care Strategies/ Use of Humor

Participants expressed multiple spiritual care strategies that they used while providing EOL care to their patients and families. Participants encouraged supporting spiritual experiences as they are profoundly healing and may enable the person to let go and die at peace. Death and dying experiences were described as complex and involved feelings of loss, spiritual pain, anxiety, loneliness, and depression. Spiritual care strategies included: a) supportive and empathetic communication; b) providing adequate information; c) providing a caring, friendly, and a healing environment; c) use of humor; d) involvement of religious rituals such as singing hymns, religious songs, watching programs on television; and e) creating a comfortable environment. For example, one of the participants said:

Many of them who are young and married, and when they are recently diagnosed, and they find out about their illness, many of their husbands leave them. Many of them are here with their mothers so they are already in depression. So, they get support if we talk to them light-heartedly or crack jokes. Many of the patients who come here say that they feel refreshed … after talking to us. We have kept a very friendly environment in the ward where we work. This is what we tell them too that whatever happens it is only for good. We don’t know how much we live but however much we live we should live it happily. (Participant 3)

Creating a friendly environment, therapeutic communication and use of humor were highly recommended to help patients and families cope at the EOL. Participants strongly recommended that spiritual care strategies can make the dying experience blissful, serene, and peaceful for patients and families. One participant said:

Sometimes we do use humor while talking to them, so they feel light (less stressed) and relax. But at the same time, we need to be careful that we should not talk about anything that is morally incorrect and may be disrespectful. Sometimes, we play television for them, they can watch different programs while they are staying here and looking after their family members. We ourselves also feel good, we spend our time well. The whole environment remains and feels good. Patients and families are already worried so these strategies give them comfort and they feel good. We also try to keep them busy and comfortable. (Participant 1)

Another participant asserted that:

When our patients are hydrated and pain free or when they start mobilizing, we feel good, it comforts us, provides a sense of internal satisfaction. I feel nothing special otherwise. If the patients remain unhappy with us, then there is no point in us working for them. (Participant 4)

Spiritual care strategies were found to be helpful and healing for everyone involved in the provision of care for the patient.

Discussion

Our findings present several social, cultural, and contextual realities of hospice and end-of-life care in a Pakistani Muslim caregiving context. The study delineates the lived experiences and perceptions of HCPs, about spirituality and spiritual care in a hospice setting. Participants showed a profound sense of attachment and belongingness in their caregiving attitudes and values toward dying patients and their families. Spirituality and spiritual care were perceived as shared human connections, relating to each other, acts of compassion, showing mutual respect while maintaining dignity in care and empowering patients and their families.

Participants described spirituality as a sense of humanity, a collective sense of togetherness, and spirit of service for the human mankind. Papadaniel et al. (2015) in their three-year anthropological study about how EOL experiences affected patients, families, and HCPs found that the illness experience was shared among the patients, family caregiver, and HCPs. This shared experience of illness and grief resulted in the development of a strong sense of attachment and shared human connections among individuals. In their study, both family caregivers and HCPs found that the shared humanity of each person was implied in the practice of “being there.” Participants in our study also stressed that spiritual care is not about identifying and treating problems, instead about being there, understanding the sufferings of the patients and families, connecting, and serving them with love and affection. In another study of patients, families and HCPs in palliative care setting, feelings of secure relationships and social connectedness enhanced spirituality, meaningfulness of life, and improve quality of life (Dobrikova et al., 2016). Thus, the perception of spirituality as a sense of humanity by HCP may improve the quality of life of those they care for.

Participants described the importance of listening to and witnessing the patient’s suffering. It was painful and exhausting but at the same time it regarded provision of compassionate care. Sinclair et al. (2006) in their study with palliative care professionals also found that rituals such as listening and providing care with love and affection are ways to open spiritual conversations and developing meaningful connections, all of which are important components of spiritual care. Nurses, psychologists, and spiritual caregivers exemplified spiritual care as connecting, listening, and witnessing to patients’ suffering (Llewellyn et al., 2015). Our findings also suggested that participants found the opportunity to reflect on their own spiritual journeys and instituted higher meaning and purpose while providing EOL care to their patients and families, especially in the context of caring for patients and families who were not only suffering with illness but with other adversities in life such as limited resources and other socioeconomic constraints. The spiritual self-reflections and shared meanings in care led them to internalize that spirituality is not only personal, rather a sense of collectiveness and shared togetherness with the humanity.

Participants described using humor as a spiritual care strategy. There is an ongoing debate in the literature about the use of humor as a healing or coping strategy in death and dying experiences. Studies have found that the use of humor is therapeutic and has been associated with increased psychological well-being, increased sociability, positive healing, and increased coping ability with adversity and hardship (Ridley et al., 2014; Rose et al., 2013); however, it needs to be used wisely by HCPs in different situations and settings (Olver & Eliott, 2014; Pinna et al., 2018). Respecting cultural and religious values of patients was an important part of providing spiritual care among the participants. The literature strongly supports that EOL care brings multiple spiritual and existential concerns which are influenced and guided by cultural values, thoughts, and actions (Abudari et al., 2016). Such values maintain integrity and wholeness while providing spiritual care.

Maintaining dignity was considered important to the participants as it allowed them to look at a person as a whole rather than just focusing on the disease, pain, or symptoms. There has been a lot of discussion in the literature around the concept of dignity and how it should be applied in the practice setting. Chochinov et al. (2015) encouraged the use of the Patient Dignity Question (PDQ) “What do I need to know about you as a person to take the best care of you that I can?”. Knowing, valuing, and respecting the person as a whole prevents a sense of depersonalization in the current era of modern medicine and promotes the use of a more patient-/family-centered approach in care. With the expression of dignity so important in EOL care, there also exists a long debate as to whether promoting dignity among patients can be taught to HCPs or whether it comes with experience (Kennedy, 2016). As our participants did not address this issue, it may be a focus for future research.

It was interesting to note in the findings that although study participants did not have any formal training or education in palliative care or spirituality, the concepts of spirituality and spiritual care were perceived as central to their inherent and learned compassionate caring values and practices. Such caring values stemmed from their own personal caring values and beliefs, personal, and professional work experience in the hospice setting. Similarly, Sinclair et al. (2006) in their study among multidisciplinary palliative care team members perception of spirituality found that spirituality was embedded in routine acts of caring and have been demonstrated in their small daily acts of kindness and love. In another recent study by Sinclair et al (2018), while conceptualizing compassion from HCPs perspective, healthcare providers suggested that personal human qualities such as love, kindness, genuineness, care, and peace were developed through family upbringing, role modeling, self-reflection, and life experience. This suggests that role modeling, self-reflection, and life experience did influence the perceptions of spirituality by our participants. Further research should determine whether these ways of learning should be part of educational programs on spirituality.

Most participants found that the provision of spiritual care was both rewarding and demanding at the same time. Participants reported feelings of emotional exhaustion, sadness, and grief while providing care to the dying patients and their families. Staying present, witnessing, and consoling the grieving as the dying patients’ suffering unfolds can be emotionally challenging for nurses and may expose them to their own vulnerabilities and finitude (Hotchkiss, 2018; Tornøe et al., 2015). Self-awareness and use of regular self-care strategies need to be in place to support HCPs health and well-being working in the hospice and home care settings as they deal with mortality, death, and dying processes (Hotchkiss, 2018; Mills et al., 2018). Having good self-care will affect the quality of empathic connection to our clients, establish a sense of mutual respect and recognition of shared humanity, and prevent burnout, frustrations, and compassion fatigue among HCPs (Mills et al., 2018). Organizational leadership should take responsibility to develop formal self-care programs for staff to promote effective spiritual care in the palliative and hospice care settings (Hotchkiss, 2018).

Study Limitations

The study was conducted in a single hospice setting and included the findings from a small sample size who self-identified as Muslim. However, findings add to the existing knowledge of importance of spirituality and spiritual care at the EOL from the perspectives of HCPs. Translating the interviews from the original language Urdu to English language may have resulted in losing some of the meaning and the essence of actual words in the data. To overcome this limitation, we kept some words in the original language in the translation.

Implications for Nursing and Health

Understanding spiritual needs and concerns of the dying patient and families is central to provide effective spiritual care in a hospice setting. Spiritual care in hospice settings includes paying attention to spirituality, showing presence, empathy, and compassion, and empowering and bringing comfort and peace to patients and families. Developing spiritual competency, education, and self-reflection of HCPs are important factors promoting spiritual care in a hospice setting. Multiple studies have identified that having self-awareness and acknowledging self-spirituality is an important element of spiritual competency and therefore all training programs should include self-reflections, i.e., having knowledge about one’s own spirituality should be obligatory (Sabry & Vohra, 2013; Sinclair et al., 2006). Additionally, the study also implied that HCPs should respect and be aware of various religious and ritual practices of their patients and families in order to attend to various spiritual care needs of their patients and families and provide compassionate and empathetic care in the hospice setting. Effective dialog with the patients and families about maintaining dignity is essential in order to achieve the goal of whole person-centered care. Kennedy (2016) discusses spiritual care strategies such as effective communication, empathetic listening, providing adequate information, attending to different rituals and other religious needs of the patients, use of humor, allowing self-reflections, using art and mature, and other activities should be encouraged to prevent spiritual distress and promote spiritual well-being of the dying individual and their families. Furthermore, hospice settings need to attend to self-care of the HCPs and self-care strategies/interventions need to be established to support HCPs in the hospice setting.

Conclusion

The study signifies the importance of spirituality and hospice care in a Pakistani Muslim context. Despite all adversities, plus the lack of death and dying care and facilities, spirituality and spiritual care were major resources of coping both among family caregivers and healthcare providers. Healthcare providers perceived spiritual care as an important dimension of palliative and EOL care. Spirituality was referred to as a sense of humanity, serving and caring for each other in order to ease suffering and promote spiritual growth and well-being of those they cared for. HCPs internalized that although listening and witnessing suffering may be painful, understanding the relationship between suffering and rituals such as listening and showing compassionate care can help them to plan effective spiritual care interventions for the patients and families. Along with the significance of spiritual care and using different spiritual care strategies for patients and families during EOL, the study also underscores the need for training HCPs for spiritual care provision and the importance of self-care needs among HCPs in the hospice setting. Further training and support can potentially enhance spiritual competency among providers. Providing spiritual care to patients and families at EOL care can be rewarding and challenging. Self-care strategies should be in place for the providers in hospice setting to maintain their health and spiritual well-being.

References

Attard, J., Ross, L., & Weeks, K. W. (2019). Developing a spiritual care competency framework for pre-registration nurses and midwives. Nurse Education in Practice, 40, 102604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2019.07.010

Abudari, G., Hazeim, H., & Ginete, G. (2016). Caring for terminally ill Muslim patients: Lived experiences of non-Muslim nurses. Palliative and Supportive Care, 14(6), 599–611.

Bernard, W. T., Maddalena, V., Njiwaji, M., & Darrell, D. M. (2014). The role of spirituality at end of life in Nova Scotia’s black community. Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work, 33(3), 353–376.

Chochinov, H. M., McClement, S., Hack, T., Thompson, G., Dufault, B., & Harlos, M. (2015). Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: Effects on patients, families, and health care providers. Journal of Pain Symptom Management, 49(6), 974–980.

Dedeli, O., Yildiz, E., & Yuksel, S. (2015). Assessing the spiritual needs and practices of oncology patients in Turkey. Holistic Nursing Practice, 29(2), 103–113.

Dobríková, P., Macková, J., Pavelek, L., AlTurabi, L., Miller, A., & West, D. (2016). The effect of social and existential aspects during end of life care. Nursing and Palliative Care, 1(3), 47–51.

El Nawawi, N. M., Balboni, M. J., & Balboni, T. A. (2012). Palliative care and spiritual care: The crucial role of spiritual care in the care of patients with advanced illness. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 6(2), 269–274.

Hotchkiss, J. T. (2018). Mindful self-care and secondary traumatic stress mediate a relationship between compassion satisfaction and burnout risk among hospice care professionals. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 35(8), 1099–1108.

Jacobs, (2019). Spiritual support at the end of life: Medical and hospice professionals are learning to meet patients’ spiritual needs. Retrieved from https://www.silvercentury.org/2019/02/spiritual-support-at-the-end-of-life/

Kennedy, G. (2016). The importance of patient dignity in care at the end of life. Ulster Medical Journal, 85(1), 45–48.

Koper, I., Pasman, H. R. W., Schweitzer, B. P., Kuin, A., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2019). Spiritual care at the end of life in the primary care setting: Experiences from spiritual caregivers-a mixed methods study. BMC Palliative Care, 18(1), 1–10.

Lalani, N., & Chen, A. (July-August, 2021). Spirituality in nursing and health: A historical context, challenges, and way forward. Holistic Nursing Practice, 35(4) (in press)

Lalani, N., Duggleby, W., & Olson, J. (2019). Rise above: Experiences of spirituality among family caregivers caring for their dying family member in a hospice setting in Pakistan. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 21(5), 422–429.

Llewellyn, H., Jones, L., Kelly, P., Barnes, J., O’Gorman, B., Craig, F., & Bluebond-Langner, M. (2015). Experiences of healthcare professionals in the community dealing with the spiritual needs of children and young people with life-threatening and life-limiting conditions and their families: Report of a workshop. BMJ Supportive Palliative Care, 5, 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000437

McSherry, W., & Jamieson, S. (2013). The qualitative findings from an online survey investigating nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(21–22), 3170–3182.

Mills, J., Wand, T., & Fraser, J. A. (2018). Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 63–73.

O’Brien, M. R., Kinloch, K., Groves, K. E., & Jack, B. A. (2019). Meeting patients’ spiritual needs during end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nurses’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of spiritual care training. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(1–2), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14648

Olver, I. N., & Eliott, J. A. (2014). The use of humor and laughter in research about end-of-life discussions. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 4(10), 80–87.

Paiva, B., Carvalho, A., Lucchetti, G., Barroso, E., & Paiva, C. (2015). “Oh, yeah, I’m getting closer to God”: Spirituality and religiousness of family caregivers of cancer patients undergoing palliative care. Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(8), 2383–2389.

Papadaniel, Y., Brzak, N., Berthod, M. (2015). Individuals and humanity: Sharing the experience of serious illness. Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie, 140(1), 131–147. Retrieved January 22, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24888295

Pinna, M. Á. C., Mahtani-Chugani, V., Sánchez Correas, M. Á., & Sanz Rubiales, A. (2018). The use of humor in palliative care: A systematic literature review. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 35(10), 1342–1354.

Puchalski, C. M. (2013). Integrating spirituality into patient care: An essential element of person-centered care. Polish Archives of Internal Medicine, 123(9), 491–497.

Richardson, P. (2014). Spirituality, religion and palliative care. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 3(3), 150–159.

Ridley, J., Dance, D., & Pare, D. (2014). The acceptability of humor between palliative care patients and health care providers. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(4), 472–474.

Rose, S. L., Spencer, R. J., & Rausch, M. M. (2013). The use of humor in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer, 23(4), 775–779.

Ross, L., & Austin, J. (2015). Spiritual needs and spiritual support preferences of people with end-stage heart failure and their carers: Implications for nurse managers. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(1), 87–95.

Sabry, W. M., & Vohra, A. (2013). Role of Islam in the management of psychiatric disorders. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(Suppl 2), S205.

Santos, H. P. O., Black, A. M., & Sandelowski, M. (2015). Timing of translation in cross-language qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 25(1), 134–144.

Sinclair, S., Raffin, S., Pereira, J., & Guebert, N. (2006). Collective soul: The spirituality of an interdisciplinary palliative care team. Palliative and Supportive Care, 4(1), 13–24.

Sinclair, S., Hack, T. F., Raffin-Bouchal, S., McClement, S., Stajduhar, K., Singh, P., Hagen, N. A., Sinnarajah, A., & Chochinov, H. M. (2018). What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: A grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. British Medical Journal Open, 8(3), e019701.

Skalla, K. A., Smith, E. M. L., Li, Z. Z., & Gates, C. (2013). Multidimensional needs of caregivers for patients with cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17(5), 500–506.

Thorne, S. E. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed.). . Routledge.

Tornøe, K. A., Danbolt, L. J., Kvigne, K., & Sørlie, V. (2015). The challenge of consolation: Nurses’ experiences with spiritual and existential care for the dying-A phenomenological hermeneutical study. BMC Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-015-0114-6

World Population Review. (2020). Karachi Population (2020). Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/karachi-population

The World Bank (2019). Population Pakistan. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=PK

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest in the study. No funding was received for the study.

Human and Animal Rights

The study involved human subjects. Ethical approval for human subjects was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Board of University of Alberta. Permission letter was obtained from the hospice in Pakistan where the data were collected.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants before the interview.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lalani, N.S., Duggleby, W. & Olson, J. “I Need Presence and a Listening Ear”: Perspectives of Spirituality and Spiritual Care Among Healthcare Providers in a Hospice Setting in Pakistan. J Relig Health 60, 2862–2877 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01292-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01292-9