Abstract

Ellis (Ellis, A. (1996), Psychotherapy, 22(1), 149–151) has been a longstanding critic of the concept of self-esteem and has offered the notion of unconditional self-acceptance as an alternative. Other researchers have suggested that cultivating mindfulness––attention directed towards one’s immediate experiences with an attitude of non-judgment––also offers a healthier alternative to self-esteem (Ryan, R. M., & Brown, K. W. (2003) Psychological Inquiry, 14(1), 71–76). This study examined the relationship between mindfulness, self-esteem, and unconditional self-acceptance. A sample of 167 university students completed two measures of everyday mindfulness, and measures of self-esteem and unconditional self-acceptance. Positive correlations were found between mindfulness, self-esteem, and unconditional self-acceptance. Mindfulness skills may offer a means to cultivate unconditional self-acceptance and to shift from an emphasis on self-esteem as a measure of worth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1991, at the third Mind and Life conference, a dialogue between the Dalai Lama and a group of leading Western scholars, the Dalai Lama was asked about low self-esteem (Goleman, 1997). After a lengthy discussion with his translator and a subsequent exchange with the other participants, the Dalai Lama admitted that he was unfamiliar with the concept, and that there was no corresponding word in his native Tibet. “I thought I had a very good acquaintance with the mind,” he confessed, “but now I feel quite ignorant” (p. 192).

Within the rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) framework, Ellis (1996) has been particularly vocal in his condemnation of the concept of self-esteem, both high and low. He has called it “perhaps the greatest emotional sickness known to humans” (p. 150), noting that self-esteem requires a global rating that fails to take into account that people are a process. He has noted the overlap in the goals of REBT and Buddhism in the dissolution of the ego, a fixed sense of self (Ellis, 1976). Within Buddhist thought, suffering is understood to be created as an individual tries to maintain a static sense of self against the backdrop of his or her constantly changing experience (Trungpa, 1973). As Ellis (1976) wrote, “You exist as an ongoing process––an individual who has a past, present, and future. Any rating of your you-ness, therefore, would apply only to ‘you’ at a single point in time and hardly to your ongoingness” (p. 347). As an alternative to self-esteem, Ellis (1996) has proposed emphasizing unconditional self-acceptance (USA), that individuals should “fully accept themselves as valuable and enjoyable human beings whether or not they are self-efficacious and whether or not others approve of or love them” (p. 150).

More recently, Ryan and Brown (2003) suggested the concept of mindfulness as a healthier alternative to self-esteem. Mindfulness involves adopting an attitude of non-judgment towards the moment-to-moment unfolding of one’s experience (Bishop et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Martin, 1997). Maintaining one’s attention in the present moment with an attitude of non-judgment allows one to become less reactive to and more accepting of one’s immediate experience (Shapiro, Carlson, Astin, & Freedman, 2006).

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between mindfulness, self-esteem, and USA. It was postulated that through mindfulness, people learn to accept their thoughts, feelings, and situations, rather than struggling against what they cannot change and measuring their worth by other’s standards. In addition, as Chamberlain and Haaga (2001a) found a relatively high degree of overlap between measures of self-esteem and USA, we expected to find a similar relationship between self-esteem and USA. We predicted that there would be a significant relationship between mindfulness, self-esteem, and USA, but between mindfulness and USA in particular.

Method

Participants & Procedure

The data for this study was taken from a larger data set of additional measures, but the entire sample was used in this study. The sample consisted of 167 Introductory Psychology students, who received experimental credit in their courses for participating. There were 118 females and 49 males. Ages ranged from 18–52, with 19 being the modal age. Participants completed measures in groups of up to 15 at a time.

Materials

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003)

The 15-item MAAS measures daily mindfulness; items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). The total mean rating is computed. Higher scores reflect greater mindfulness. The authors consciously excluded items that reflect attitudinal components (e.g., acceptance), possible benefits of mindfulness (e.g., well being and calmness), and refined levels of consciousness. Internal consistency with a student population is high (α = .82). The MAAS has exhibited acceptable convergent and discriminant validity with other measures of mindfulness, emotional clarity, and openness to experience.

Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale—Revised (CAMS-R; Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, & Greeson, 2003)

The 12-item scale CAMS-R measures everyday mindfulness and focuses on the degree to which examinees experience their thoughts and feelings. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (rarely/not at all) to 4 (almost always). Scores on the scale are summed. Higher scores reflect greater mindfulness. Internal consistency across the 12 items is acceptable for two student samples (α = .74–.80). The CAMS-R has exhibited acceptable convergent and discriminant validity with other measures of mindfulness, emotional clarity, avoidance, and over-engagement.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965)

The 10 items making up the RSE are rated on a 4-point Guttman scale from 3 (strongly agree) to 0 (strongly disagree). Scores on the scale are summed. It has high internal consistency (α = .92) and is the most widely used assessment of self-esteem in research, although there has been concern that it loads on two different factors of self-esteem, positive and negative (Heatherton & Wyland, 2003). The RSE has been found to be positively correlated with the MAAS (Brown & Ryan, 2003).

Unconditional Self-Acceptance Questionnaire (USAQ; Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001a)

Based on the notion derived from rational-emotive behavior therapy that the construct of self-esteem reflects attitudes that are unhealthy, the 20-item USAQ measures the extent to which individuals accept themselves in a way that is not contingent upon self-evaluation. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (almost always untrue) to 7 (almost always true). Scores on the scale are summed. A revised version with different wording of three questions that had exhibited negative item-remainder correlations was used in this study (Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001b). For example, Chamberlain & Haaga changed, “I set goals for myself with the hope that they will make me happy (or happier)” to, “When I am deciding on goals for myself, trying to gain happiness is more important than trying to prove myself.” Internal consistency is high (α = .86). The USAQ has been shown to correlate with the RSE, r (103) = .56, p < .001, suggesting some overlap in constructs; however, although high self-esteem correlates with narcissism, high self-acceptance does not (Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001a). Convergent and discriminant validity appear to be acceptable.

Results

Internal Consistency of Measures

In order to establish the reliability of the measures, a reliability analysis was conducted on all participants’ completed responses. In all measures, Cronbach’s alpha was above .70: MAAS (α = .84), CAMS-R (α = .79), RSE (α = .87), and USAQ (α = .79).

Mindfulness, Self-Esteem, and Self-Acceptance

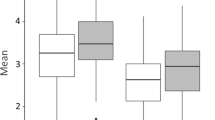

Mindfulness was measured using the MAAS and the CAMS-R, self-esteem was measured using the RSE, and unconditional self-acceptance was measured using the USAQ. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were computed between the MAAS, CAMS-R, RSE, and USAQ. Significant relationships were found between the RSE and the MAAS [r = .39, p = .001], and between the RSE and the CAMS-R, [r = .50, p = .001]. There was a significant relationship between the USAQ and the MAAS [r = .31, p = .001], between the USAQ and the CAMS-R [r = .45, p = .001]. There was, also, a significant relationship between the RSE and USAQ [r = .51, p = .001] and between the MAAS and CAMS-R [r = .60, p = .001]. (See Table 1.)

We hypothesized that the USAQ would have a stronger correlation with mindfulness than the RSE. As the RSE correlations were, if anything, higher than those of the USAQ, we did not run analyses comparing the correlations, as it was already clear that results did not support this aspect of our hypothesis.

Discussion

The results of the current study support the idea that everyday mindfulness is related to unconditional self-acceptance and self-esteem. This suggests that individuals who are more mindful have greater unconditional self-acceptance and self-esteem. The correlation between the MAAS and the RSE was similar to the findings of Brown and Ryan (2003), and the correlation between the RSE and USAQ was similar to that found by Chamberlain and Haaga (2001a, b). As Chamberlain and Haaga have suggested, the relatively high correlation between the RSE and USAQ may reflect a weakness in the measures; or there may be a great deal of overlap between self-esteem and self-acceptance, and that perhaps the self-appraisal component may be what distinguishes between the two. It is also possible that the distinction between self-esteem and unconditional self-acceptance is too subtle for the average person to distinguish. There may have been something of a halo effect, where participants were more likely to give all positive or all negative answers about themselves. Regardless, it may be important to explore concepts or descriptors that are unique to unconditional self-acceptance and which distinguish it from self-esteem. Results do not suggest that mindfulness is more strongly related to unconditional self-acceptance than to self-esteem.

One possible reason that unconditional self-acceptance showed no stronger relationship to mindfulness than self-esteem may be related to the aspects of mindfulness that the MAAS and CAMS-R emphasize. Both are measures of everyday mindfulness, and only the CAMS-R specifically includes an acceptance component (Feldman et al., 2003). Since this study was conducted, new measures of mindfulness have emerged that attempt to capture different facets of mindfulness. For example, the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS) has four facets: observe, describe, act with awareness, and accept without judgment (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004). More recently, a factor analysis of items from five different mindfulness measures-including the KIMS, MAAS, and CAMS-R-yielded five facets that were combined into the Five-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Kreitemeyer, & Toney, 2006). The FFMQ subscales are: nonreactivity to inner experience; observing/noticing/attending to sensations/perceptions/thoughts/feelings; acting with awareness/automatic pilot/concentration/nondistraction; describing/labeling with words; and non-judging of experience. As they both involve a withholding of judgment, it is possible that the accept without judgment subscale of the KIMS and the non-judging of experience subscale of the FFMQ may be more related to unconditional self-acceptance than the MAAS and the CAMS-R, which are uni-dimensional measures of everyday mindfulness. Subsequent studies may explore this possible relationship.

Overall, although the results of this study do not suggest that mindfulness is related more to the construct of unconditional self-acceptance than that of self-esteem, it does take a step in bringing mindfulness research into the REBT theoretical model. Ellis (1984) recognized the value of meditation more than two decades ago and acknowledged that it may be utilized as a useful component in REBT; however, there appears to be little overlap in the research literature between REBT and mindfulness.

Conceptually, as mindfulness appears to help foster a less ego-centered approach to one’s experience and promote greater acceptance of the present moment, the cultivation of mindfulness may increase unconditional self-acceptance. Unfortunately, the overlap between the measures of self-esteem and unconditional self-acceptance in this study make it impossible to distinguish whether there is a unique relationship between mindfulness and unconditional self-acceptance. An additional limitation of the study is that the mindfulness measures appear to capture only a few aspects of mindfulness-mainly mindfulness in everyday life. More comprehensive measures of mindfulness such as the KIMS and the FFMQ may offer additional information about the relationship between mindfulness and unconditional self-acceptance, and if there is anything unique in this relationship from that of mindfulness and self-esteem.

References

Baer R. A., Smith G. T., & Allen K. B. (2004) Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11(3):191–206

Baer R. A., Smith G. T., Hopkins J., Krietemeyer J., & Toney L. (2006) Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1):27–45

Bishop S. R., Lau M., Shapiro S., Carlson L., Anderson N. D., Carmody J., et al. (2004) Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 11(3):230–241

Brown K. W., & Ryan R. M. (2003) The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4):822–848

Chamberlain J. M., & Haaga D. A. F. (2001a) Unconditional self-acceptance and psychological health. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 19(3):163–176

Chamberlain J. M., & Haaga D. A. F. (2001b) Unconditional self-acceptance and responses to negative feedback. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 19(3):177–189

Ellis A. (1976) RET abolishes most of the human ego. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 13(4):343–248

Ellis A. (1984) The place of meditation in cognitive-behavior therapy and rational emotive therapy. In D. H. Shapiro, R. N. Walsh (Eds.) Meditation: Classic and contemporary perspectives pp. 671–673 New York: Aldine,

Ellis A. (1996) How I learned to help clients feel better and get better. Psychotherapy, 22(1):149–151

Feldman, G. C., Hayes, A. M., Kumar, S. M., & Greeson, J. M. (2003) Clarifying the construct of mindfulness: Relations with emotional avoidance, over-engagement, and change with mindfulness training. Paper presented at the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Boston, MA

Goleman, D. (Ed.). (1997) Healing emotions: Conversation with the Dalai Lama on mindfulness, emotions, and health. Boston & London: Shambhala

Heatherton, T. F., & Wyland, C. L. (2003) Assessing self-esteem. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.) Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 219–233). Washington, DC: APA

Kabat-Zinn J. (2003) Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 10(2):144–156

Martin J. R. (1997) Mindfulness: A proposed common factor. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 7,291–312

Rosenberg M. (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Ryan R. M., & Brown K. W. (2003) Why we don’t need self-esteem: On fundamental needs, contingent love, and mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 14(1):71–76

Shapiro S. L., Carlson L. E., Astin J. A., & Freedman B. (2006) Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3):373–386

Trungpa C. (1973) Cutting through the spiritual materialism. Boston & London: Shambhala

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was based on data collected for the first author's Master's project.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, B.L., Waltz, J.A. Mindfulness, Self-Esteem, and Unconditional Self-Acceptance. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 26, 119–126 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0059-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0059-0