Abstract

Analysis of siliceous microfossils of a 79 cm long peat sediment core from Highlands Hammock State Park, Florida, revealed distinct changes in the local hydrology during the past 2,500 years. The coring site is a seasonally inundated forest where water availability is directly influenced by precipitation. Diatoms, chrysophyte statospores, sponge remains and phytoliths were counted in 25 samples throughout the core. Based on the relative abundance of diatom species, the record was subdivided into four diatom assemblage zones, which mainly reflect the hydrological state of the study site. An age-depth relationship based on radiocarbon measurements of eight samples reveals a basal age of the core of approximately 2,500 cal. yrs. BP. Two significant changes of diatom assemblage composition were found that could be linked to both, natural and anthropogenic influences. At 700 cal. yrs. BP, the diatom record documents a shift from tychoplanktonic Aulacoseira species to epiphytic Eunotia species, indicating a shortening of the hydroperiod, i.e. the time period during which a wetland is covered by water. This transition was interpreted as being triggered by natural climate change. In the middle of the twentieth century a second major turnover took place, at that time however, as a result of human impact on the park hydrology through the construction of dams and canals close to the study site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The unique position of Florida between the temperate North American mainland and the tropical Caribbean Islands is reflected in the diverse and specific environments on the peninsula. Water availability is a dominant controlling factor in the mosaic of landscapes (Myers and Ewel 1990). Understanding the response of these environments to hydrological fluctuations forced by climate change as well as human disturbance is crucial for the conservation and restoration plans of the natural areas, as well as regulating the natural resources as groundwater, which is essential for sustaining households and agriculture (Ehrenfeld 2000; Reese 2002).

Long-term records of environmental change in the peninsula’s terrestrial realm are available from pollen analysis of lake deposits from the numerous lakes on the Lake Wales Ridge (Watts 1969, 1975, 1980; Watts et al. 1992; Grimm et al. 1993; Watts and Hansen 1994). The observed major vegetation shifts from dry, oak-dominated landscapes to wetter, pine-dominated landscapes over the past 60,000 years are related to Dansgaard-Oeschger interstadials (Grimm et al. 1993, 2006; Donders et al. 2009). Moreover, hydrological changes occurring in the coastal region are increasingly covered by palynological and geochemical studies on estuarine deposits, reflecting the environmental response to the Holocene sea level rise super-imposed on climatic changes since the last glacial maximum (Willard et al. 2007; Cremer et al. 2007; Van Soelen et al. 2010). While millennial-scale hydrological dynamics are well documented, the minor changes occurring on multi-decadal to multi-centennial time scales are more difficult to deduce from these archives, as the more subtle responses of the environment to these changes are likely smoothed in the regional signal covered in lake and estuarine deposits.

Peat deposits accumulating in the many wetlands of the Florida peninsula are a potentially suitable archive for the reconstruction of short-lived hydrological dynamics of multi-annual to multi-decadal climate variability, of which the El Niño—Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) are known to strongly affect Florida precipitation patterns (Donders et al. 2005a; Curtis 2008). As the sand-covered limestone subsurface of this region is highly permeable, vegetation and fauna are largely dependent on precipitation for their water supply (Kushlan 1990). Consequently, minor changes in local hydrology, expressed as changes of the water depth or hydroperiod (the time period per year during which a site is flooded) are found to result in distinct environmental changes (Gaiser et al. 1998; Willard et al. 2001; Willard et al. 2004; Donders et al. 2005b).

The analysis of siliceous microfossils has proven to be a highly useful method for reconstructing past changes in aquatic environments. As siliceous algae, like diatoms, chrysophytes, and freshwater sponges have specific habitat preferences, variation in the species assemblage or fossil abundance provides information on changes within the aquatic environment like water depth, hydroperiod and pH (Smol and Stoermer 2010; Wujek 2000; Zeeb and Smol 2001; Frost 2001). Shifts in phytolith assemblages can furthermore be linked to changes in plant groups from which they originate, in response to changes in the local environment (Piperno 2001; Prebble and Shulmeister 2002; Lu et al. 2006).

Diatoms in particular have proven to be a successful tool in reconstructing local hydrological changes. They are characterized by high species diversity and short reproductive rates leading to fast floral alterations under environmental change (Smol and Stoermer 2010). Intensive efforts to deduce water quality changes in Florida surface waters have demonstrated the sensitivity of diatom communities and the applicability of diatom-based transfer functions to determine nutrient status and hydrological conditions in coastal wetlands (Gaiser et al. 2005; Cremer et al. 2007; Wachnicka et al. 2010). Although diatoms have been also successfully applied to deduce past hydrological conditions in freshwater wetlands in the Atlantic coastal plain (Gaiser et al. 2004), diatom-based hydrological reconstructions for central Florida wetlands are so far underrepresented.

Here we present diatom and other siliceous microfossils analyses on a ~2,500 year old peat core from a swamp forest in Highlands Hammock State Park, Florida. The combined analysis of siliceous microfossils allows for detailed and more robust interpretation of the changes in this wetland. Based on these observed changes we aim to reconstruct past environmental dynamics induced by subtle hydrological changes, and thus develop better insight in climate and anthropogenic driven variability in the central Florida hydrology.

Study area

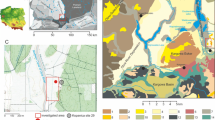

Highlands Hammock State Park is situated in Hardee and Highlands Counties about 6 km west of Sebring, Florida (Fig. 1). The state park comprises 36 km2 and is located on the western edge of the Lake Wales Ridge, a relict shoreline formed at sea-level highstands during the Yarmouth and Sangamon interglacials of the Pleistocene. At the edge of the ridge in the east of the park lies the highest elevation (46 m a.s.l.) from where the land slopes gradually down. Along the western edge of the park the surface is more elevated again, due to the presence of another beach ridge. The lower parts of the park at around 24 m a.s.l., between the ridges, hold the drainage basin of Little Charlie Bowlegs Creek, flowing from south to north along the park’s western boundary. Two smaller creeks emerge in the east and flow westward through the park, finally merging with Little Charlie Bowlegs Creek. Tiger Branch in the north springs from a permanent seepage from the beach ridge, whereas Haw Branch in the south is a seasonal creek, springing from the Seven Lake district (Fig. 1) and only flowing during periods of sufficient water supply. When entering the basin section of the park, both streams dissipate into a westward sheetflow. At times of establishment of the park in the 1930s the local hydrology was altered by the construction of canals, roads and bridges. The primary purpose of these modifications was to ensure an adequate water supply to the central hammock vegetation, in order to protect it from wildfires, a naturally occurring phenomenon in this environment which at the time was regarded as a serious threat to the park’s main attraction, the hydric hammock (FDEP 2007).

The occurrence of natural plant communities in the park strongly reflects the local topography and hydrology. The drier areas at higher elevations are characterized by mesic flatwoods (mainly Florida slash pine, Pinus elliottii, with an undergrowth of predominantly saw palmetto, Serenoa repens), whereas the wetter surroundings of Little Charlie Bowlegs Creek hold mostly basin swamp and marsh vegetation (Baldcypress (Taxodium distichum), swamp laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia), sweetgum (Liquidambar) and red maple (Acer rubrum)). Along the minor waterways, around the hydric hammock, in the central area of the park, so called baygall vegetation is found, consisting mostly of sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana), loblolly bay (Gordonia lasianthus) and swamp bay (Persea palustris) with a diverse undergrowth, e.g. dahoon holly (Ilex cassine), waxmyrtle (Myrica cerifera) and royal ferns (Osmunda spp.). The central feature of the park is the hydric hammock, dominated by a variety of hardwood species like live oak (Quercus virginiana), sweet gum (Liquidambar styraciflua), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), together with cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto) and a dense understory of various shrubs, ferns and epiphytes. Within the hammock a number of ‘domes’ are present due to karstic solution features, where pop ash (Fraxinus caroliniana) and swamp tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) are common.

Materials and methods

Coring and dating

Sediment core HHA3 (N 27°27′47.45″, W 81°32′21.48″) was collected on April 1st, 2008, just south of the road bordering South Canal in Highlands Hammock State Park (Fig. 1). The coring site is located in a baygall forest dominated by red maple (Acer rubrum) and sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana) trees and fern (Osmunda spp.) undergrowth. The 79 cm long core was retrieved by subsequently hammering down and digging out a PVC pipe (diameter: 12 cm), and then cut lengthwise and subsampled in 1 cm intervals for geochemical and microfossil analysis. Radiocarbon dating using Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) was performed on plant remains and bulk material from seven samples at Poznań Radiocarbon Laboratory, Poland and one sample at Beta Analytic, Florida, USA (Table 1). The age-depth relationship (Fig. 2) was established using the open-source R code package “clam” (Blaauw 2010). The amount of organic material in the sediments was determined with the loss on ignition (LOI) method following Heiri et al. (2001).

Sample processing and diatom analysis

Siliceous microfossil samples were freeze-dried and approximately 1 gram of each sample was used for the extraction of diatom valves. Samples were treated subsequently with hydrogen peroxide (1.5 h at 100°C), hydrochloric acid and nitric acid (2 h at 120°C) for the removal of organic matter and carbonate. Excess acid was removed by seven sedimentation procedures in demineralized water. Microscopic slides were prepared using evaporation trays (Battarbee 1973; Cremer et al. 2001). A known fraction of the cleaned samples in solution was allowed to settle on a cover slip and, after evaporation of the excess water, mounted on slides using the high refraction mountant Naphrax®. On each slide at least 400 diatom valves were counted with a Leica DM2500 microscope equipped with a 63× oil immersion lens and differential interference contrast at a magnification of 945×. Digital images were taken with a Leica DFC320 digital camera. Diatom taxonomy for the most identified species followed Camburn and Charles (2000), Patrick and Reimer (1966), Siver et al. (2005), Gaiser and Johansen (2000), Metzeltin and Lange-Bertalot (2007) and Pearce et al. (2010). A principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to our dataset to create a zonation of the core based on the diatom assemblages (Birks 2010). The PCA was run on the diatom species relative abundance (no data transformation) using the C2 software package (Juggins 2007).

Microfossil abundance determination

The absolute abundance of siliceous microfossils per gram dry sediment was determined by using the methods described in Battarbee (1973). The amount of microfossils per gram dry sediment was calculated considering the mass of dry sediment per sample, the amount of the sample solution that was used to prepare the slide, and the number of siliceous microfossils per surface unit on the cover slip,. Sponge megascleres were broken in most cases; therefore, one count was defined as the occurrence of two spicule endings.

Results

Core lithology and chronology

Core HHA3 entirely consists of dark brown, mostly homogeneous peat (Fig. 2). LOI percentages ranged from 15 to 84%, with a sharp transition at 50 cm depth from relatively lower values in the bottom part of the core to relatively higher organic content in the upper part (Fig. 2). Plant remains become more abundant and less degraded towards the upper part of the core. A well-constrained age model based on eight AMS radiocarbon dates indicates a basal age of the core of approximately 2,500 cal. year BP (Table 1, Fig. 2). For the 79 cm core, this means one centimeter represents on average 32 yrs of sediment accumulation. In the lower parts of the core this goes up to 50 yrs/cm, due to compaction and further degradation of the organic matter.

Siliceous microfossils

Diatom valves, chrysophyte statospores, phytoliths and sponge spicules were well-preserved and abundant throughout the core. A total of 33 diatom taxa representing 13 genera were found in the 25 studied samples. The core was subdivided into four diatom assemblage zones, supported by a principle components analysis (PCA) of the entire diatom taxa assemblage (Fig. 3). The downcore pattern in absolute concentrations of all groups of siliceous microfossils was similar, except for the sponge spicules, which were present only in the lower half of the core (Fig. 4). The total diatom concentration varied between 6 and 373 × 106 valves per gram dry weight, while concentrations for the other siliceous fossil were lower by an order of magnitude. Absolute concentrations of all four groups peaked around 70 cm depth (2000 cal. yrs. BP) and gradually declined up core until 15 cm depth (AD 1910). The relative abundance of all identified diatom taxa occurring with a minimum of 3% in at least one sample (Table 2) are shown in Fig. 4, while light and scanning electron microscope images of these taxa are presented in Fig. 5. The most abundant genera throughout the record were Aulacoseira and Eunotia.

Abundance of siliceous microfossils in core HHA3 including diatom zonation. Left: relative abundance of most frequently occurring diatom (abundance of minimum 3% in at least one sample). Right: absolute abundance of four groups of siliceous microfossils, units are in 106 microfossils per gram dry sediment

Diatom species from sediment core HHA3. a–c: Aulacoseira coroniformis. a: LM image of two spine-linked valves belonging to two frustules in girdle view. b: LM image of valve in face view. c: SEM image. d: Eunotia incisa: LM image in face view. e, f: Eunotia carolina: SEM (e) and LM (f) images, both in face view. g: Eunotia pocosinensis: LM image in face view. h, i: Eunotia zygodon var. elongata: LM (h) and SEM (i) images, both in face view. j, k: Eunotia zygodon var. zygodon: LM (k) and SEM (j) images, both in face view. l, m: Eunotia tautoniensis: LM image (l) in face view, SEM image (m) in girdle view. n: Eunotia naegelii: LM image in face view. o, p: Pinnularia viridis: LM (p) and SEM (o) images, both in face view. q–s: Fragilaria javanica: LM image (q) in face view, SEM images of valve detail in girdle view (r) and face view (s). t, u: Diadesmis confervacea: LM (t) and SEM (u) images, both in face view. v: Pinnularia parvulissima: LM image of valve in face view. w: Pinnularia microstauron: LM image of valve in face view. x: Frustulia crassinervia: LM image of valve in face view. y, z: Frustulia saxonica: LM (z) and SEM (y) images, both in face view. Black scale bar is 20 μm for all LM images. Scale bars in SEM images: 5 μm (c, r, s, u), 10 μm (j), 20 μm (i, m, y) and 50 μm (o)

Diatom zone 1 (35–79 cm), representing the age range from 2,511 to 700 cal. yrs. BP, was dominated by the tychoplanktonic diatom species Aulacoseira coroniformis Pearce et Cremer (>80%) and was characterized by the presence of sponge spicules. The transition between zone 1 and zone 2, ranging from 35–24 cm (700–276 cal. yrs. BP), was gradual. Aulacoseira coroniformis was gradually replaced by Eunotia zygodon Ehrenberg and Pinnularia viridis Ehrenberg. At the boundary between zone 2 and zone 3, from 24 to 12 cm (276 cal. yrs. BP—AD 1957), the species composition changed within the genus Eunotia. The abundance of Eunotia zygodon and Eunotia zygodon var. elongata Hustedt decreased while Eunotia carolina Patrick and Eunotia tautoniensis Hustedt increased in abundance. The uppermost 11 cm representing the last 50 years (zone 4) were characterized by an increase of the absolute concentrations of both diatoms and phytoliths (Fig. 4). This zone also included Fragilaria javanica Hustedt and Frustulia saxonica Rabenhorst, which were not recorded in older sediment samples of this core.

Discussion

Each of the four defined diatom zones were palaeoecologically interpreted based on the autecological requirements of the single diatom species as found in the literature, if available (Table 2). Previous studies have shown that the presence of multiple groups of siliceous microfossils can be useful in interpreting the hydrological history of shallow basins (Gaiser et al. 2004). However, our analysis of different microfossil groups revealed minor or no variability in phytoliths and chrysophyte statospores in the core, therefore our interpretation of past hydrologic conditions was based on diatom and sponge spicule data only.

-

Diatom zone 1 (2,511–700 cal. year BP)

-

Environment: permanently flooded acidic wetland.

The dominance of Aulacoseira coroniformis, usually found in shallow, acidic (pH optimum around 5) wetlands (Pearce et al. 2010), in combination with the high number of sponge spicules suggested a wetland habitat with permanently flooded freshwater conditions (Frost 2001; Quillen 2009). Tychoplanktonic species of the genus Aulacoseira are known to be comparably thickly silicified and, as a consequence, to sink faster compared to weaker silicified diatoms species. Therefore, such tychoplanktonic life forms require a certain degree of water turbulence in order to maintain their position in the productive zone of the water column (Wolin and Stone 2010; Vélez et al. 2003; Bradbury 2000). Aulacoseira coroniformis indicated a considerable hydrological flow and thus, a continuous influx of silica at the coring site. This suggested that the present day seasonal inflow from Haw Branch to the coring site would have been the permanent state during the accumulation of diatom zone 1 sediments. Haw Branch’s water budget is nowadays fed by a small lake in the south-eastern area of the park (Fig. 1), the water level of which is directly influenced by precipitation.

-

Diatom zones 2 and 3 (700 cal. year BP to AD 1957)

-

Environment: seasonally inundated acidic wetland.

The shift in diatom assemblage composition from the tychoplanktonic A. coroniformis to epiphytic species of mainly the genera Eunotia and Pinnularia at the transition from zone 1 to zone 2 suggested lower water levels and a considerable shortening of the local hydroperiod (Gaiser et al. 1998) at that time. This interpretation implied that the landscape and habitat structure significantly changed in the thirteenth century. Work by Willard et al. (2006) on pollen assemblages in the Florida Everglades shows that the timing of tree island initiation and maturation corresponded to periods of multidecadal droughts in the region of which one period from AD 1,200–1,400 corresponds to the observed drying at the transition from diatom zone 1 to 2 in our core HHA3. Diatom analysis of lake sediments from the nearby Lake Annie (Quillen 2009), however, showed no major changes in the assemblages at this time and describe the interval from 4,000 to 100 cal. yrs. BP as the ‘stable lake phase’ without pronounced fluctuations in lake levels or lake chemistry. The precipitation induced changes in the hydrology might have been too subtle to be recorded in the large water body of Lake Annie, while the shallow basin environment of the Highlands Hammock wetland responded more sensitive to even slight changes in water availability. Lower water levels combined with reduced upland input significantly affected the habitats of both sponges and tychoplanktonic diatoms as A. coroniformis. The most abundant diatom species in zones 2 and 3 were Eunotia zygodon, Eunotia carolina, Pinnularia viridis and Eunotia tautoniensis, all of which are known to be acidophilous species with pH optima around 5 (Siver et al. 2005; Gaiser and Johansen 2000). This indicated that acidity likely did not significantly change at the transition between zones 1 and 2. The boundary between zones 2 and 3 showed a shift from Eunotia zygodon and Pinnularia viridis towards Eunotia carolina and Eunotia tautoniensis. Since the pH requirements of these species are in a comparable range, the palaeoecological background of this shift was difficult to interpret. The transition from zones 2 to 3 was probably due to small-scale, lake-inherent changes including for example change of habitat availability, interspecific competition, and chemical composition of lake water.

-

Diatom zone 4 (AD 1957–Present)

-

Environment: wetland pond affected by human impact

The data of the youngest diatom zone reflected a distinctly modified composition of the diatom assemblage and a clear species diversification. A number of previously unobserved species were identified including Fragilaria javanica and species of the genus Frustulia (Fig. 4). The genus Eunotia, which comprised up to 90% of the diatom assemblage in zones 2 and 3, was still present in large numbers, but less dominant. The diatom assemblages of zone 4 consisted of considerable numbers of Fragilaria javanica (up to 40%) and Frustulia saxonica (max. 21%). The latter two species are known to be acidophilous (Hustedt 1938; Gaiser and Johansen 2000), which could mean that there was no major pH change at the transition from zone 3 to zone 4. Water depth optima for Frustulia saxonica and Frustulia crassinervia Lange-Bertalot et Krammer compared to those for the dominant taxa in zone 3 pointed to a slight increase of water depth at the site (Gaiser and Johansen 2000; Siver et al. 2005). Historical records from the twentieth century showed that in the 1930s and 1940s a number of canals were dug throughout the park, altering the sheet flow coming from Haw Branch. These activities certainly had a great effect on the local water system and water availability as well as quality at the coring site (FDEP 2007). Although the main goal of the channel building was to redirect the incoming water in order to permanently flood the hydric hammock in the central area of the park, the construction of an elevated road just north of our coring site most likely has led to increased water availability there. Although it was not possible to link the observed changes of the diatom assemblages at the transition between zone 3 and zone 4 to a single environmental parameter, it is obvious that the various infrastructural measures in the park affected the availability of diatom habitats and species composition of diatom communities.

Conclusions

The studied peat sequence from Highlands Hammock State Park beared well-preserved siliceous microfossil assemblages, including a diverse and abundant diatom flora. Detailed diatom analysis of the peat core revealed changes in the local hydrological state during the past 2,500 years. From 2,500 cal. year BP to 700 cal. year BP, the diatom assemblage were dominated by a tychoplanktonic species of the genus Aulacoseira, indicating a permanently flooded wetland environment. After 700 cal. year BP, the diatom record suggested a shortening of the local hydroperiod. The dominance of acidophilous, epiphytic Eunotia species from 700 cal. year BP onwards was the result of this decreased water level. Since water levels and the hydroperiod at the coring location are directly tied to a precipitation-fed seasonal creek, the observed drying was likely caused by climatic changes, i.e. decreased precipitation. The last turnover in the diatom assemblage occurred in the twentieth century and coincided with intensive human activities in the Highlands Hammock State Park. Through the construction of canals, elevated roads and dams, the hydrography was altered in such a way that the local water availability at our coring location was increased.

The study of diatoms from wetland peat sediments is well suited for the reconstruction of hydrological parameters such as water depth and hydroperiod. A shallow basin that is seasonally inundated is very sensitive to both natural and anthropogenic driven variations in the local hydrology, and the diatom community shows a clear response to these changes. The presence or absence of sponge spicules provides valuable additional palaeoecological information whereas no significant variation in the abundance of chrysophyte cysts and phytoliths was found.

Environmental reconstructions based on sediments from only one coring location are limited to a mainly local signal which makes it difficult to link observed changes to larger scale environmental and climatic phenomena. In order to reconstruct climate variability on a more regional scale, a number of sediment cores from different locations representing a larger area would have to be incorporated. Finally, a problem in the paleoecological interpretation of fossil diatom assemblages is the limited reliable knowledge of the autecological requirements of most of the species present in the studied sediment core. This can only be resolved by extensive taxonomic survey of diatoms and water monitoring in this region combined with the development of modern training sets.

References

Battarbee RW (1973) A new method for the estimation of absolute microfossil numbers, with reference especially to diatoms. Limnol Oceanogr 18:647–653

Birks HJB (2010) Numerical methods for the analysis of diatom assemblage data. In: Smol JP, Stoermer EF (eds) The diatoms: applications for environmental and earth sciences. Cambridge University press, Cambridge, pp 23–54

Blaauw M (2010) Methods and code for ‘classical’ age-modelling of radiocarbon sequences. Quat Geochronol 5:512–518

Bradbury JP (2000) Limnologic history of Lago de Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, Mexico for the past 48, 000 years: impacts of climate and man. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 163:69–95

Camburn KE, Charles DF (2000) Diatoms of low-alkalinity lakes in the Northeastern United States. Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Philadelphia

Cremer H, Wagner B, Melles M, Hubberten HW (2001) The postglacial environmental development of Raffles Sø, East Greenland: inferences from a 10, 000 year diatom record. J Paleolimnol 26:67–87

Cremer H, Sangiorgi F, Wagner-Cremer F, McGee V, Lotter AF, Visscher H (2007) Diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) and Dinoflagellate Cysts (Dinophyceae) from Rookery Bay, Florida, USA. Caribb J Sci 43:23–58

Curtis S (2008) The Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and extreme daily precipitation over the US and Mexico during the hurricane season. Clim Dyn 30:343–351

Donders TH, Wagner F, Dilcher DL, Visscher H (2005a) Mid-to late-Holocene El Niño-Southern Oscillation dynamics reflected in the subtropical terrestrial realm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:10904–10908

Donders TH, Wagner F, Visscher H (2005b) Quantification strategies for human-induced and natural hydrological changes in wetland vegetation, southern Florida, USA. Quat Res 64:333–342

Donders TH, de Boer HJ, Finsinger W, Grimm EC, Dekker SC, Reichart GJ, Wagner-Cremer F (2009) Impact of the Atlantic Warm Pool on precipitation and temperature in Florida during North Atlantic cold spells. Climate Dynamics 1–10. doi:10.1007/s00382-009-0702-9

Ehrenfeld JG (2000) Defining the limits of restoration: the need for realistic goals. Rest Ecol 8:2–9

FDEP (2007) Highlands Hammock State Park Unit Management Plan. State of Florida, Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Recreation and Parks

Frost TM (2001) Freshwater sponges. In: Smol JP, Birks HJB, Last WM (eds) Tracking environmental change using lake sediments. Vol 3. Terrestrial, algal, and siliceous indicators. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 253–263

Gaiser EE, Johansen J (2000) Freshwater diatoms from Carolina Bays and other isolated wetlands on the Atlantic coastal plain of South Carolina, USA, with descriptions of seven taxa new to science. Diatom Res 15:75–130

Gaiser EE, Philippi TE, Taylor BE (1998) Distribution of diatoms among intermittent ponds on the atlantic coastal plain: development of a model to predict drought periodicity from surface-sediment assemblages. J Paleolimnol 20:71–90

Gaiser EE, Brooks MJ, Kenney WF, Schelske CL, Taylor BE (2004) Interpreting the hydrological history of a temporary pond from chemical and microscopic characterization of siliceous microfossils. J Paleolimnol 31:63–76

Gaiser EE, Wachnicka A, Ruiz P, Tobias F, Ross M (2005) Diatom indicators of ecosystem change in subtropical coastal wetlands. In: Bortone SA (ed) Estuarine indicators. CRC Press Boca Raton, Florida., pp 127–144

Grimm EC, Jacobsen GL, Watts WA, Hansen BCS, Maasch KA (1993) A 50,000-year record of climate oscillations from florida and its temporal correlation with the heinrich events. Science 261:198–200

Grimm EC, Watts WA, Jacobsen GL, Hansen BCS, Almquist HM, Dieffenbacher-Krall AC (2006) Evidence for warm wet Heinrich events in Florida. Quat Sci Rev 25:2197–2211

Heiri O, Lotter AF, Lemcke G (2001) Loss on ignition as a method for estimating organic and carbonate content in sediments: reproducibility and comparability of results. J Paleolimnol 25:101–110

Hustedt F (1938) Systematische und ökologische Untersuchungen über die Diatomeen-Flora von Java, Bali und Sumatra nach dem Material der Deutschen Limnologischen Sundaexpedition. E. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart

Juggins S (2007) C2 version 1.5 user guide. Software for ecological and palaeoecological data analysis and visualisation. Newcastle University, Newcastle

Krammer K (2000) The genus Pinnularia. In: Lange-Bertalot H (ed) Diatoms of Europe: diatoms of the European inland waters and comparable habitats. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.G, Ruggell, pp 1–703

Kushlan JA (1990) Freshwater marshes. In: Myers RL, Ewel JJ (eds) The ecosystems of Florida. University of Central Florida Press, Orlando, Florida, pp 324–363

Levin I, Kromer B (2004) The tropospheric 14CO2 level in mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (1959–2003). Radiocarbon 46:1261–1272

Lu HY, Wu NQ, Yang XD, Jiang H, Liu KB, Liu TS (2006) Phytoliths as quantitative indicators for the reconstruction of past environmental conditions in China I: phytolith-based transfer functions. Quat Sci Rev 25:945–959

Metzeltin D, Lange-Bertalot H (2007) Tropical diatoms of South America II. Special remarks on biogeography disjunction. In: Lange-Bertalot H (ed) Iconogr diatomol. Annotated diatom micrographs. vol 18. Diversity-taxonomy-biogeography. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.G, Ruggell, pp 1–877

Myers RL, Ewel JJ (1990) Ecosystems of Florida. University of Central Florida Press, Orlando, Florida

Patrick R, Reimer CW (1966) The diatoms of the United States, exclusive of Alaska and Hawaii. vol 1. fragilariaceae, eunotiaceae, achnanthaceae, naviculaceae. Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Philadelphia

Pearce C, Cremer H, Wagner-Cremer F (2010) Aulacoseira coroniformis sp. nov., a new diatom (Bacillariophyta) species from Highlands Hammock State Park, Florida. Phytotaxa 13:40–48

Piperno DR (2001) Phytoliths. In: Smol JP, Birks HJB, Last WM (eds) Tracking environmental change using lake sediments. Vol 3: Terrestrial, algal, and siliceous indicators. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 235–251

Prebble M, Shulmeister J (2002) An analysis of phytolith assemblages for the quantitative reconstruction of late Quaternary environments of the Lower Taieri Plain, Otago, South Island, New Zealand II. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction. J Paleolim 27:415–427

Quillen AK (2009) Diatom-based paleolimnological reconstruction of quaternary environments in a Florida Sinkhole Lake, PhD-dissertation. Florida International University, Miami

Reese RS (2002) Inventory and review of aquifer storage and recovery in southern Florida. U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 02:4036, pp 1–56

Reimer PJ, Baillie MGL, Bard E, Bayliss A, Beck JW, Blackwell PG, Ramsey CB, Buck CE, Burr GS, Edwards RL, Friedrich M, Grootes PM, Guilderson TP, Hajdas I, Heaton TJ, Hogg AG, Hughen KA, Kaiser KF, Kromer B, McCormac FG, Manning SW, Reimer RW, Richards DA, Southon JR, Talamo S, Turney CSM, van der Plicht J, Weyhenmeyer CE (2009) IntCal09 and Marine09 radiocarbon age calibration curves, 0–50, 000 years CAL BP. Radiocarbon 51:1111–1150

Scherer RP (1988) Freshwater diatom assemblages and ecology/palaeoecology of the Okefenokee swamp/marsh complex, Southern Georgia. U.S.A. Diatom Res 3:129–157

Siver PA, Hamilton PB, Stachura-Suchoples K, Kociolek JP (2005) Diatoms of North America: the freshwater flora of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, U.S.A. In: Lange-Bertalot H (ed) Iconographia Diatomologica. vol. 14. Diatoms of North America. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.G, Ruggell, pp 1–463

Smol JP, Stoermer EF (2010) The diatoms: applications for environmental and earth sciences, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Van Soelen EE, Lammertsma EI, Cremer H, Donders TH, Sangiorgi F, Brooks GR, Larson RA, Sinninghe-Damsté Wagner-CremerF, Reichart G-J (2010) Late Holocene sea-level rise in Tampa Bay: Integrated reconstruction using biomarkers, pollen, organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts, and diatoms. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 86:216–224

Vélez MI, Hooghiemstra H, Metcalfe S, Martínez I, Mommersteeg H (2003) Pollen—and diatom based environmental history since the Last Glacial Maximum from the Andean core Fúquene-7, Colombia. J Quat Sci 18:17–30

Wachnicka A, Gaiser EE, Boyer J (2010) Ecology and distribution of diatoms in Biscayne Bay, Florida (USA): implications for bioassessment and paleoenvironmental studies. Ecol Ind 11:622–632

Watts WA (1969) A pollen diagram from Mud Lake, Marion County, north-central Florida. Geol Soc Am Bull 80:631–642

Watts WA (1975) A late quaternary record of vegetation from Lake Annie, southcentral Florida. Geology 3:344–346

Watts WA (1980) The late quaternary vegetation history of the southeastern United States. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 11:387–409

Watts WA, Hansen BCS (1994) Pre-Holocene and Holocene pollen records of vegetation history from the Florida peninsula and their climatic implications. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 109:163–176

Watts WA, Hansen BCS, Grimm EC (1992) Camel lake: A 40 000-yr record of vegetational and forest history from northwest Florida. Ecology 73:1056–1066

Willard DA, Weimer LM, Riegel WL (2001) Pollen assemblages as paleoenvironmental proxies in the Florida Everglades. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 113:213–235

Willard DA, Bernhardt CE, Weimer L, Cooper SR, Gamez D, Jensen J (2004) Atlas of pollen and spores of the Florida Everglades. Palynology 28:175

Willard DA, Bernhardt CE, Holmes CW, Landacre B, Marot M (2006) Response of Everglades tree islands to environmental change. Ecol Monogr 76:565–583

Willard DA, Bernhardt CE, Brooks GR, Cronin TM, Edgar T, Larson R (2007) Deglacial climate variability in central Florida, USA. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 251:366–382

Wolin JA, Stone JR (2010) Diatoms as indicators of water level change in freshwater lakes. In: Smol JP, Stoermer EF (eds) The diatoms: applications for environmental and earth sciences. Cambridge University press, Cambridge, pp 174–185

Wujek DE (2000) Identification, ecology, and distribution of silica-scale bearing chrysophytes from the Carolinas. I. Piedmont region. J Elisha Mitchell Sci Soc 116:307–323

Zeeb BA, Smol JP (2001) Chrysophyte scales and cysts. In: Smol JP, Birks HJB, Last WM (eds) Tracking environmental change using lake sediments. Vol. 3: Terrestrial, algal, and Siliceous Indicators. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 203–223

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the cooperation of State Park District 4 staff and the support of Ken Alvarez (FDEP) during fieldwork. Jan van Tongeren (Utrecht University) is acknowledged for assisting with sample and slide preparation in the lab. Evelyn Gaiser (Florida State University) contributed many fruitful discussions and constructive comments on the manuscript. This study is part of the Hurricanes and Global Change Program funded by Utrecht University and is the Netherlands Research School of Sedimentary Geology publication no 2011.10.02. The paper is part of a special issue on South Florida supported by the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological Research Program (National Science Foundation Grant No. DEB-9910514).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pearce, C., Cremer, H., Lammertsma, E. et al. A 2,500-year record of environmental change in Highlands Hammock State Park (Central Florida, U.S.A.) inferred from siliceous microfossils. J Paleolimnol 49, 31–43 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-011-9557-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-011-9557-2