Abstract

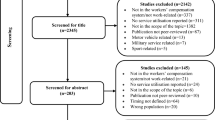

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to assist ill and injured workers to stay-at-work or to return-to-work. Purpose The purpose of this scoping review is to identify primary care physicians’ learning needs in returning ill or injured workers to work and to identify gaps to guide future research. Methods We used established methodologies developed by Arksey and O’Malley, Cochrane and adapted by the Systematic Review Program at the Institute for Work & Health. We used Distiller SR©, an online systematic review software to screen for relevance and perform data extraction. We followed the PRISMA for Scoping Reviews checklist for reporting. Results We screened 2106 titles and abstracts, 375 full-text papers for relevance and included 44 studies for qualitative synthesis. The first learning need was related to administrative tasks. These included (1) appropriate record-keeping, (2) time management to review occupational information, (3) communication skills to provide clear, sufficient and relevant factual information, (4) coordination of services between different stakeholders, and (5) collaboration within teams and between different professions. The second learning need was related to attitudes and beliefs and included intrinsic biases, self-confidence, role clarity and culture of blaming the patient. The third learning need was related to specific knowledge and included work capacity assessments and needs for sick leave, environmental exposures, disclosure of information, prognosis of certain conditions and care to certain groups such as adolescents and pregnant workers. The fourth learning need was related to awareness of services and tools. Conclusions There are many opportunities to improve medical education for physicians in training or in continuing medical education to improve care for workers with an illness or injury that affect their work.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Carey TS, Hadler NM. The role of the primary physician in disability determination for social security insurance and workers’ compensation. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104(5):706–710.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Ferrier S, et al. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):582–590.

Wanberg CR. The individual experience of unemployment. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:369–396.

Hildebrandt J, Pfingsten M, Saur P, et al. Prediction of success from a multidisciplinary treatment program for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1997;22(9):990–1001.

Scheel IB, Hagen KB, Oxman AD. Active sick leave for patients with back pain: all the players onside, but still no action. Spine. 2002;27(6):654–659.

Canadian Medical Association. The treating phyisicians role in helping patients return to work after an illness or injury 2013. https://policybase.cma.ca/documents/policypdf/PD13-05.pdf Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. 2019 Healthcare professionals’ Consensus Statement for Action Statement for Health and Work 2019. https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Health-Work_Consensus_Statement_090419.pdf Accessed 1 Oct 2020.

Talmage JB, Mehorn J, Hyman M (2011) Why staying at work or returning to work is in the patient’s best interest. In: Talmage JB, Mehorn J, Hyman M, editors. AMA guides to the evaluation of work ability and return to work. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL

Papagoras H, Pizzari T, Coburn P, et al. Supporting return to work through appropriate certification: a systematic approach for Australian primary care. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):164–167.

Alvino EC, Ahmad TM. How to determine whether our patients can function in the workplace: a missed opportunity in medical training programs. Permanente Journal. 2019;23:18–259.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, MacEachen E, et al. What are physicians told about their role in return to work and workers’ compensation systems? An analysis of Canadian resources. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety. 2019;17(1):78–89.

The Association of Worker’s Compensation Boards of Canada. National work injury, disease and fatality statistics Mississauga, ON, Canada: The Association of Worker’s Compensation Boards of Canada; 2015. https://awcbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2012-2014-NWISP-Publication-for-2015.pdf Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

International Labour Organization. The prevention of occupational diseases Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_208226.pdf Accessed 1 Oct 2020.

Nelson DI, Nelson RY, Concha-Barrientos M, et al. The global burden of occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):446–458.

Punnett L, Prüss-Ütün A, Nelson DI, et al. Estimating the global burden of low back pain attributable to combined occupational exposures. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):459–469.

Trupin L, Earnest G, San Pedro M, et al. The occupational burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462–469.

Morabia A, Markowitz S, Garibaldi K, et al. Lung cancer and occupation: results of a multicentre case-control study. Br J Ind Med. 1992;49(10):721–727.

Blanc PD, Toren K. How much adult asthma can be attributed to occupational factors? Am J Med. 1999;107(6):580–587.

Beach J, Cherry N. Course participation and the recognition and reporting of occupational ill-health. Occup Med. 2019;69(7):487–493.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Cochrane Training. Scoping reviews: what they are and how you can do them: Cochrane; 2017. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/scoping-reviews-what-they-are-and-how-you-can-do-them Accessed 1 Oct 2020.

Irvin E, Van Eerd D, Amick BC 3rd, et al. Introduction to special section: systematic reviews for prevention and management of musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(2):123–126.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Tonima S, et al. (2016) The role of health-care providers in the workers' compensation system and return-to-work process: final report. Toronto: Institute for Work & Health

Atkins S, Reho T, Talola N, et al. Improved recording of work relatedness during patient consultations in occupational primary health care: a cluster randomized controlled trial using routine data. Trials. 2020;21(1):256.

Simmons JM, Liebman AK, Sokas RK. Occupational health in community health centers: practitioner challenges and recommendations. New Solut. 2018;28(1):110–130.

Aarseth G, Natvig B, Engebretsen E, et al. “Working is out of the question”: a qualitative text analysis of medical certificates of disability. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):55.

Gray SE, Brijnath B, Mazza D, et al. Australian general practitioners’ and compensable patients: factors affecting claim management and return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):672–678.

Balasooriya-Smeekens C, Bateman A, Mant J, et al. How primary care can help survivors of transient ischaemic attack and stroke return to work: focus groups with stakeholders from a UK community. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(693):e294–e302.

Christie N, Beckett K, Earthy S, et al. Seeking support after hospitalisation for injury: a nested qualitative study of the role of primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(642):e24–e31.

Sylvain C, Durand MJ, Maillette P, et al. How do general practitioners contribute to preventing long-term work disability of their patients suffering from depressive disorders? A qualitative study BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:71.

Vanmeerbeek M, Govers P, Schippers N, et al. Searching for consensus among physicians involved in the management of sick-listed workers in the Belgian health care sector: a qualitative study among practitioners and stakeholders. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):164.

Yagil D, Eshed-Lavi N, Carel R, et al. Return to work of cancer survivors: predicting healthcare professionals’ assumed role responsibility. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(2):443–450.

Anastas TM, Miller MM, Hollingshead NA, et al. The unique and interactive effects of patient race, patient socioeconomic status, and provider attitudes on chronic pain care decisions. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(10):771–782.

Dorrington S, Carr E, Stevelink SAM, et al. Demographic variation in fit note receipt and long-term conditions in south London. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(6):418–426.

Riiser S, Haukenes I, Baste V, et al. Variation in general practitioners’ depression care following certification of sickness absence: a registry-based cohort study. Fam Pract. 2021;38(3):238–245.

Brijnath B, Mazza D, Kosny A, et al. Is clinician refusal to treat an emerging problem in injury compensation systems? BMJ Open. 2016;6(1): e009423.

Mandal R, Dyrstad K. Explaining variations in general practitioners’ experiences of doing medically based assessments of work ability in disability benefit claims a survey-based analysis. Cogent Medicine. 2017;4(1):1368614.

Hinkka K, Niemela M, Autti-Ramo I, et al. Physicians’ experiences with sickness absence certification in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2019;47(8):859–866.

Yanar B, Kosny A, Lifshen M. Perceived role and expectations of health care providers in return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(1):212–221.

Lippel K, Eakin JM, Holness DL, et al. The structure and process of workers’ compensation systems and the role of doctors: a comparison of Ontario and Quebec. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59(12):1070–1086.

Moßhammer D, Michaelis M, Mehne J, et al. General practitioners’ and occupational health physicians’ views on their cooperation: a cross-sectional postal survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89(3):449–459.

Stratil J, Rieger MA, Voelter-Mahlknecht S. Optimizing cooperation between general practitioners, occupational health and rehabilitation physicians in Germany: a qualitative study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2017;90(8):809–821.

Sanders T, Wynne-Jones G, Nio Ong B, et al. Acceptability of a vocational advice service for patients consulting in primary care with musculoskeletal pain: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of general practitioners, vocational advisers and patients. Scandinavian J Public Health. 2019;47(1):78–85.

Lundberg T, Melander S. Key push and pull factors affecting return to work identified by patients with long-term pain and general practitioners in sweden. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(11):1581–1594.

Bertilsson M, Maeland S, Love J, et al. The capacity to work puzzle: a qualitative study of physicians’ assessments for patients with common mental disorders. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1–4.

de Kock CA, Lucassen PLBJ, Spinnewijn L, et al. How do Dutch GPs address work-related problems? A focus group study. European Journal of General Practice. 2016;22(3):169–175.

de Kock CA, Lucassen P, Bor H, et al. Training GPs to improve their management of work-related problems: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. European Journal of General Practice. 2018;24(1):258–265.

King R, Murphy R, Wyse A, et al. Irish GP attitudes towards sickness certification and the “fit note.” Occup Med. 2016;66(2):150–155.

Godycki-Cwirko M, Nocun M, Butler CC, et al. Family practitioners’ advice about taking time off work for lower respiratory tract infections: a prospective study in twelve European primary care networks. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10): e0164779.

Nordhagen HP, Harvey SB, Rosvold EO, et al. Case-specific colleague guidance for general practitioners’ management of sickness absence. Occup Med. 2017;67(8):644–647.

Ruseckaite R, Collie A, Scheepers M, et al. Factors associated with sickness certification of injured workers by General Practitioners in Victoria. Australia BMC Public Health. 2016;16:298.

Sekoni KI, Jamil H. Completing disability forms efficiently and accurately: curriculum for residents. Primer. 2018;2:9.

Marell L, Lindgren M, Nyhlin KT, et al. “Struggle to obtain redress”: women’s experiences of living with symptoms attributed to dental restorative materials and/or electromagnetic fields. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2016;11:32820.

Scharf J, Angerer P, Muting G, et al. Return to work after common mental disorders: a qualitative study exploring the expectations of the involved stakeholders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6635.

Coole C, Nouri F, Narayanasamy M, et al. Total hip and knee replacement and return to work: clinicians’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(9):1247–1254.

Peters SE, Coppieters MW, Ross M, et al. Health-care providers’ perspectives on factors influencing return-to-work after surgery for nontraumatic conditions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2020;33(1):87–87.

Dwyer CP, MacNeela P, Durand H, et al. Judgment analysis of case severity and future risk of disability regarding chronic low back pain by general practitioners in Ireland. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3): e0194387.

Dwyer CP, MacNeela P, Durand H, et al. Effects of biopsychosocial education on the clinical judgments of medical students and GP trainees regarding future risk of disability in chronic lower back pain: a randomized control trial. Pain Med. 2020;21(5):939–950.

Mann A, Tator CH, Carson JD. Concussion diagnosis and management: knowledge and attitudes of family medicine residents. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(6):460–466.

Schouten B, Bergs J, Vankrunkelsven P, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on the prevalence, barriers and management of psychosocial issues in cancer care: a mixed methods study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(1): e12936.

Stergiou-Kita M, Pritlove C, Kirsh B. The, “Big C”: stigma, cancer, and workplace discrimination. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):1035–1050.

Graves JM, Klein TA. Nurse practitioners’ comfort in treating work-related injuries in adolescents. Workplace Health Saf. 2016;64(9):404–413.

Heitmann K, Svendsen HC, Sporsheim IH, et al. Nausea in pregnancy: attitudes among pregnant women and general practitioners on treatment and pregnancy care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(1):13–20.

Bohatko-Naismith J, Guest M, James C, et al. Australian general practitioners’ perspective on the role of the workplace Return-to-Work Coordinator. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(6):502–509.

Elbers NA, Chase R, Craig A, et al. Health care professionals’ attitudes towards evidence-based medicine in the workers’ compensation setting: a cohort study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:1–12.

King J, Cleary C, Harris MG, et al. Employment-related information for clients receiving mental health services and clinicians. Work. 2011;39(3):291–303.

Unger D, Kregel J. Employers’ knowledge and utilization of accommodations. Work. 2003;21(1):5–15.

McDowell C, Fossey E. Workplace accommodations for people with mental illness: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):197–206.

Corbière M, Mazaniello-Chézol M, Bastien MF, et al. Stakeholders’ role and actions in the return-to-work process of workers on sick-leave due to common mental disorders: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30(3):381–419.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joanna Liu for library support and to acknowledge the following people for helping to determine relevance of non-English language studies: Morgane Le Pouesard, Heather Johnston, Paolo Maselli, Joanna Liu, Hitomi Suzuki, Rina Shoki, Sylvia Snoeck-Krygsman, Mariska de Wit, and Tania Bruno.

Funding

This project was funded by a Research Grant from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Furlan, A.D., Harbin, S., Vieira, F.F. et al. Primary Care Physicians’ Learning Needs in Returning Ill or Injured Workers to Work. A Scoping Review. J Occup Rehabil 32, 591–619 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10043-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10043-w