Abstract

Purpose

A shift from providing long-term disability benefits to promoting work reintegration of people with remaining work capacity in many countries requires new instruments for work capacity assessments. Recently, a practice-based instrument addressing biopsychosocial aspects of functioning, the Social Medical Work Capacity instrument (SMWC), was developed. Our aim was to examine the content validity of the SMWC using ICF core sets.

Methods

First, we conducted a systematic search to identify relevant ICF core sets for the working age population. Second the content of these core sets were mapped to assess the relevance and comprehensiveness of the SMWC. Next, we compared the content of the SMWC with the ICF-core sets.

Results

Two work-related core sets and 31 disease-specific core sets were identified. The SMWC and the two work-related core sets overlap on 47 categories. Compared to the work-related core sets, the Body Functions and Activities and Participation are well represented in the new instrument, while the component Environmental factors is under-represented. Compared to the disease-specific core sets, items related to the social and domestic environmental factors are under-represented, while the SMWC included work-related factors complementary to the ICF.

Conclusion

The SMWC content seems relevant, but could be more comprehensive for the purpose of individual work capacity assessments. To improve assessing relevant biopsychosocial aspects, it is recommended to extend the instrument by adding personal and environmental (work- and social-related) factors as well as a more tailored use of the SMWC for assessing work capacity of persons with specific diseases or underlying illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increasing rates of long-term sickness absence and work disability in an ageing population have obliged several countries to shift their focus from providing long-term disability benefits and social protection programmes to promoting the work reintegration of people with partial or residual work capacity [1,2,3]. By introducing policy reforms, many countries have shifted their focus away from assessing disability on predominantly medical grounds to the assessment of the remaining work capacity of disability benefit claimants [4].

Several countries have developed new assessment instruments over the last ten years to assess individuals’ abilities to participate in the labour market actively, to assess barriers which may restrict work participation, and to indicate directions interventions may take to overcome barriers for work participation [4, 5]. These new assessment instruments have shifted from predominantly focusing on loss of physical and/or mental functioning, towards assessment of work capacity from a holistic perspective, i.e. the ability to participate actively in the labour market from physical, mental, social, and societal perspectives. Instead of the traditional disability assessment instruments, new instruments should not only assess limitations in activities [6], but also incorporate personal and environmental factors [1] which could mitigate limitations in activities when appropriate adjustments are applied. Although a biopsychosocial approach [3, 4, 6] has been integrated into many of these instruments, the literature about the validity of these instruments is limited.

Recognizing the interaction of activity limitations with the particular requirements of the individual’s work context led to the development of a novel approach for work capacity assessments by the Dutch Social Security Institute, the Institute for employee benefits schemes (UWV). The Social Medical Work Capacity instrument, SMWC, was developed by a panel of experts of the UWV (e.g. staff members, labour experts, and insurance physicians) and based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [7]. It has been developed to help the UWV professionals asssessing a clients’ ability to participate in work and to provide indications and/or advice for reintegration support to optimize the use of available potential and finding a good jobmatch [6, 8, 9]. The instrument was pilot tested in practice and showed that professionals using the instrument were positive as it provides a structure for describing the clients work capacity and their possibilities to participate in work [10, 11]. However, the professionals also critizised the large amount of items making the instrument timely in its use. Providing a better evidence base for the content of the instrument could improve utility of this new instrument in practice. Therefore, insight is needed whether all included items are relevant.

To examine the relevance of items needed to assess claimants’ remaining work capacity, it is important to evaluate the content validity of the SMWC, i.e. the degree to which the content of the instrument is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured [12, 13], and to evaluate whether all items are relevant and comprehensive for the construct to be measured [14]. To validate the content of the SMWC, ICF core sets can be of potential benefit to determining these factors. They provide a minimum standard for the assessment and reporting of functioning and health [15]. Each ICF core set includes a selection of essential categories from the full ICF classification considered most relevant for describing the functioning and environmental factors of a person with a specific health condition or in a specific healthcare context. ICF core sets are frequently used in daily practice by clinicians and other professionals for the assessment and reporting of functioning and health [15].

The overall aim of the present study was to examine the content validity of SMWC by comparing the content of the instrument with ICF core sets.

Method

The Social Medical Work Capacity instrument (SMWC)

The Social Medical Work Capacity instrument, SMWC, was developed by a group of experts working as professionals at the Dutch Social Security Institute, the Institute for employee benefits schemes (UWV). The instrument is designed to guide social security professionals in taking a biopsychosocial approach when creating an overview of a person’s work capacity and what is needed to find a good jobmatch [8, 9]. The 129 items of SMWC related to 95 2nd level ICF categories, of which 54 from the Body Functions, 35 from Activities and Participation, and six from Environmental factors. With the exception of Chapter 6 (domestic life) and Chapter 9 of Activities and Participation (Community, social and civic life), all Chapters of the Classification of Body Functions and the Classification of Activities and Participation are represented in the SMWC. The SMWC does not include categories from the Classification of Body Structures. The ICF categories of the Classification of Environmental factors are mostly related to the work environment, such as climate, light, sound, vibration, and air quality (Chapter 1 and 2). Some ICF categories were further specified in the SMWC to provide more detail of work capacity items which is needed to exploit this capacity in actual work. Supplementary Table S2 presents a full overview of included ICF categories in the SMWC.

Procedure

First, we conducted a systematic search to identify relevant articles on relevant core sets for the working age population. Second the content of these core sets were mapped to the content of the SMWC. Next, we compared the content of the SMWC with the ICF-core sets.

ICF Core Sets

Medline, PsycINFO (both using Ebsco), and Web of Science were searched using the terms ‘disability evaluation’, ‘work capacity’, and ‘work ability’ combined with search terms identifying assessment instruments (including questionnaires) and ICF core sets [15]. The full search strategy can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The databases were searched for articles published between January 2000 and July 2018. Although the ICF was published in 2001, the year 2000 was also included as there was already a draft version of the ICF available.

Selection of Articles

Articles were included if they described the development of an ICF core set and presented final results. Letters to the editor, guidelines, editorials, book Chapters, dissertations, conference proceedings, design papers or case reports were excluded. Core sets were included if they were designed for the assessment of the functioning of working age (18–65) people with a specific disease or for their assessment in a work-related setting. A core set was excluded if the context precluded work, e.g. in acute or post-acute settings and geriatric settings. Additionally, core sets were excluded if they were developed in a too specific setting (e.g. applicable in a specific country). The ICF Research Branch website was checked for completeness [16]. A first selection based on title and abstract was conducted by two independent reviewers. When the reviewers could not reach consensus, a third reviewer was consulted. When the title and abstract did not provide enough information to decide if the inclusion criteria were met, the article was included for full-text screening. Disease-specific core sets are grouped into disease groups in line with the ICD-10 [17] and in accordance with the most prevalent diseases of people claiming disability benefits.

Data Extraction

First, data regarding core set, study aim, number of ICF categories included, and methods used were extracted from the included full-text articles by two reviewers. The methodological quality of the core set development was described taking ‘the guide on how to develop an ICF core set’ by Selb et al. [15] as the gold standard. When this gold standard was not applied in the development, the method used was described. Second, all ICF categories included in the core sets were registered. Data extraction was limited to the second level order of ICF categories. Figure 1 shows the hierarchical structure of the ICF classification. To allow for comparison with ICF core sets, the SMWC was compared on 2nd level ICF categories, collapsing items of 3rd and 4th level under the related 2nd level category.

To structure the results, the included 31 disease-specific core sets were grouped into disease groups in line with the ICD-10 [17] and in accordance with the most prevalent diseases of people claiming disability benefits [18, 19]. Two work-related core sets completed the total inclusion of 33 core sets.

Content Comparison of SMWC with ICF Categories

First, to evaluate whether the SMWC contains all relevant items for the purpose of holistic work capacity assessments, a comparison was made with the two work-related core sets as these core sets are related to the construct of the SMWC.

Second, to evaluate whether the SMWC is comprehensive and thus covers all relevant aspects of the construct to be measured and whether all included items of the SMWC are relevant for the construct, we compared the content of the SMWC to the content of all retrieved ICF core sets, going beyond a specific work-related focus. This allowed for comparing the SMWC with core sets developed for reporting on functioning and health, and may lead to identification of common indicators across disease specific core sets which are possibly relevant to include in the new instrument. We used a relevance ranking by calculating the relative frequency of each ICF category within the disease groups. Scores of 0% indicated that an ICF category was not included in any core set, and scores of 100% indicated that an ICF category was included in all core sets of that particular disease group. Presentation of this relevance ranking was restricted to scores higher than 70%, a rather arbitrary cut-off. Subsequently, these common indicators were compared to the content of the work capacity instrument.

Results

Search

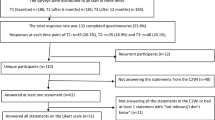

The combined searches yielded 3376 hits (1950 in Medline/PubMed, 637 in PsycINFO, 789 in Web of Science). After removal of duplicates, a total of 2267 abstracts were identified and 277 full-text articles on core sets were read. Forty-five articles described the development of a core set and presented the final results. Of these, 33 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included. A reference check of the included articles and a check of the ICF Research Branch website did not identify additional articles or core sets. However, our search retrieved three core sets that were not included on the website. Figure 2 depicts how the core sets were selected, and Table 1 provides a description of the characteristics of the included articles and two work-related and 31 disease specific core sets.

Content Comparison of SMWC with ICF Categories

Work-Related Core Sets

The two work-related core sets are the Vocational Rehabilitation core set and the Disability Evaluation core set (see Text Box 1 for a further description). The SMWC, existing of 129 categories, and the two work-related core sets overlap on 47 categories (36% of the SMWC), mainly in Chapters Mental functions (b1), Learning and applying knowledge (d1), General tasks and demands (d2), Mobility (d4), Interpersonal interactions (d7), and Natural environment and human made changes to environment (e2) (see Table 2; Supplemental Figure S1). As well as the SMWC, both work-related core sets do not include categories from the Classification of Body Structures. The SMWC overlaps on 17 categories with the Disability Evaluation core set (13.2% of the SMWC) and 46 with the Vocational Rehabilitation core set (35.7% of the SMWC). A total of 54 ICF categories are included in the SMWC but not in any work-related core set (41.9% of the SMWC), of which N = 37 are from the Body functions, reflecting mainly physical and mental functions. In turn, the work related core sets contain 44 ICF categories not included in the SMWC, with the majority from the component of Environmental factors (N = 28). For instance, the Vocational Rehabilitation core set includes Environmental factors within the four ICF Chapters Products and technology (e1), Support and relationships (e3), Attitudes (e4), and Services, systems and policies (e5), which are all not included in SMWC (see Table 2). The Disability Evaluation core set does not include any Environmental factors because no consensus could be reached during its development on which factor to include [11]. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for an overview of overlap between the SMWC and the two work-related core sets on the ICF components (Table 3).

Disease-Specific Core Sets

The 33 disease-specific core sets were grouped into musculoskeletal conditions, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, neurological conditions, mental conditions, and cancers, see Text Box 2 for a further description and grouping. First, when looking at the distribution of included ICF categories across the disease groups, the ICF categories are more or less equally divided over the Body Functions, Activities and Participation and Environmental factors, while 7.4% are from the Body structures.

The distribution of ICF categories across the ICF components in the SMWC differs from the distribution across disease-specific core sets, with 52.5% from Body Functions, 41.4% from Activities and Participation, and 6.1% from Environmental factors. No categories from the Body Structures are included, see Fig. 3. ICF categories with relative frequencies above 70% are in the Body Functions (N = 6), Activities and Participation (N = 14), and Environmental factors (N = 11), see Text Box 1. When comparing the content of the SMWC with the disease specific core sets on Chapter level, we see overlap in 10 ICF categories with high relative frequencies (> 70%) that are included in most disease specific core sets and the SMWC. Of these, four categories are from the Body functions and six from the Activities and Participation component, see Table 3. Highly frequent ICF categories in the disease specific core sets that are not included in the SMWC are related to social factors, e.g. friends, family and colleagues, factors related to taking care of oneself, e.g. washing, eating, caring for body parts, doing housework, and related to health professionals and systems.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the content validity of the SMWC by comparing its content with ICF core sets. Comparison of the SMWC with the included work-related and disease specific core sets showed that the SMWC covers most of the relevant items on Body functions and Activities and Participation, however, most of the Environmental factors were lacking.

The relative strong focus on Body functions and Activities and Participation level may be due to the legal context in which the SMWC was developed and used. The SMWC was developed to provide a holistic view of work capacity, including medical history taking and attention to activity limitations and participation restrictions, influencing this capacity [8, 9]. Because of the legal constraints, the assessment is highly protocolized, leaving limited room to take personal and environmental factors into account. This might explain the scarse inclusion of these additional factors in the SMWC. When the outcomes are to be used to provide a holistic assessment of a persons’ residual work capacity and what is needed to find a good jobmatch, the content of the SMWC may therefore not be comprehensive enough. In line with the ICF framework, a dynamic interaction between health and personal and environmental factors are likely to have a direct or indirect influence on a persons’ work capacity [20, 21].

Work-related factors included in the SMWC are in particular assessing the physical work environment (e.g. heat, sound, air quality) and physical job demands, i.e. work endurance, working hours, and level of work exertion. Factors on psychosocial job demands (e.g. job content, decision authority, supervisor and colleagues support) are lacking. With the purpose of jobmatching in mind, additional environmental factors of the work place were included during the SMWC development, additional to the ICF. These factors are based on the content of currenty used methods for work capacity assessments, and relate to, for example work endurance [23]. However, to achieve a jobmatch, not only information about the person and hypothetical workplace factors are needed, but also knowledge about the physical and psychosocial job demands. Since the importance of work-related factors in the assessment of work capacity has long been recognised [22, 23], and that both physical and psychosocial job demands are predictors for work participation [24, 25], it is strongly recommended to extent the SMWC with this type of work characteristics in the work capacity assessment.

Highly frequent social factors, e.g. friends and family, and factors related to taking care of oneself, e.g. washing, eating, caring for body parts, doing housework, illustrate that ICF categories related to the social context might also be relevant to include in the SMWC. This is in line with findings of a recent systematic review showing the relevance of including the social context for work capacity. They concluded that several cognitive behavioural factors of significant others (like friends or family) can facilitate or hinder work participation [26]. When asked, insurance physicians also considered the context of community life, social life and civic life in addition to disease related factors and functions and structures as important factors for work capacity assessments [65].

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is the use of ICF core sets in examining the content validity of the SMWC, which is in line with recent recommendations by the WHO and others to use the ICF in work disability assessments [22, 27]. Using the ICF framework to evaluate the content validity of the SMWC is a strong and novel approach and allows for a more structured assessment in comparison to expert judgements [14]. The ICF framework provides a holistic view of the person and provides a unified language for expressing these assessments, and core-set development is often standardized and published in peer reviewed publications. An additional strength is the systematical approach in identifying ICF core sets in the literature.

Some limitations should also be reported. The ICF does not operationalize personal factors and lacks specific work-related environmental factors [28,29,30,31]. Information about the work context or personal factors might provide valuable information relevant for work capacity evaluation as they possibly act as barriers or facilitators for work participation and are currently not included in our overview. Second, there is criticism regarding the development of core sets as they have a biomedical connotation, while the aim of the ICF is a biopsychosocial approach [15].

Implications for Research and Practice

The SMWC was developed to guide the social security experts in taking a biopsychosocial approach when creating an overview of a person’s work capacity and what is needed to find a good jobmatch. However, we showed that the instrument still has a focus on Body functions and Activities and Participation, and could be further developed by including additional factors to take into account the home situation (e.g. attitudes and relationships with friends and family), personal care (e.g. washing and doing housework), and workplace factors. Comparisons with disease specific core sets showed additional blind spots in the SMWC content. Further research could also focus on a more tailored use of the SMWC for specific diseases or underlying illness. The content comparisons with the disease specific core sets could therefore be a starting point for selection of relevant content. In addition, more research is needed to identify additional items in particular focussing on the work context, i.e. the implications of functioning problems for work opportunities, the barriers to participation in work, and the workplace adjustments or interventions required to overcome these barriers and achieve a good jobmatch. Work endurance, dealing with different types of working hours, level of exertion, estimating own options, overseeing the consequences of own actions, and achieving workpace are some examples of work related items that are found in the SMWC and not present in the ICF framework [51] and therefore also not identified in the core sets of our review. Additionally, aspects of the psychosocial work environment are important factors for finding a good jobmatch. It is therefore recommended to add these factors to the SMWC and possibly to the ICF framework, see also table S2. To further develop and improve precision and practical use of the SMWC, tailored subsets of the instrument should be identified together with insurance physicians and labor experts, combined with existing literature on barriers and facilitators in the work context or personal factors in various disease groups.

Conclusion

The SMWC content seems relevant, but needs to be more comprehensive for the purpose of use in work capacity assessments, as it has a relatively strong focus on body functions and activities and participation. To better achieve it’s goal in taking a biopsychosocial approach when creating an overview of a person’s work capacity and what is needed to find a good jobmatch, it is recommended to extend the instrument by adding personal and environmental factors, such as social factors and domestic factors, as well as more specific work related factors. To improve the use of the SMWC in practice, it is recommended to select the relevant disease-specific categories out of the comprehensive instrument, to aid a tailored use of the instrument.

References

AIR. One size does not fit all: A new look at the labor force participation of people with disabilities. Washington: American Institutes for Research (AIR); 2015.

Vornholt K, Villotti P, Muschalla B, Bauer J, Colella A, Zijlstra F, Van Ruitenbeek G, Uitdewilligen S, Corbière M. Disability and employment: overview and highlights. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2018;27(1):40–55.

OECD. Transforming disability into ability: Policies to promote work and income security for disabled people. Paris: OECD; 2003.

Bickenbach J, Posarac A, Cieza A, Kostanjsek N. Assessing disability in working age Population: a paradigm shift: From impairment and functional limitation to the disability approach. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2015. Report nr ACS14124.

OECD. New ways of addressing partial work capacity. thematic review on sickness, disability and work issues paper and progress report. OECD; 2007.

Geiger BB, Garthwaite K, Warren J, Bambra C. Assessing work disability for social security benefits: international models for the direct assessment of work capacity. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(24):2962–2970.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO.

Centraal Expertise Centrum UWV. Compendium participation Act. Wajong and SMWC (SMBA) v.1.0. Amsterdam: UWV; 2015.

UWV. The making of SMBA. Amsterdam: UWV; 2015.

Sengers J, Abma FI, Brouwer S. Report survey study on the utility of the Method SMWC (SMBA). Groningen: University Medical Center Groningen; 2015.

UWV. Praktijktoets SMBA. Amsterdam: UWV; 2014.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–549.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, Bouter LM, De Vet HC. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10(1):22.

de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol D. Measurement in medicine. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

Selb M, Escorpizo R, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, Üstün B, Cieza A. A guide on how to develop an international classification of functioning, disability and health core set. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51(1):105–117.

ICF Research Branch-ICF Core Sets Project. https://www.icf-research-branch.org/icf-core-sets-projects2. Accessed 17 Jun 2017.

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problem (10th ed.). (1990). https://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/. Accessed 17 Jun 2017.

UWV. UWV jaarverslag 2015. Amsterdam: UWV; 2016.

Black DC. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London: TSO; 2008.

Dekkers-Sanchez PM, Wind H, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. What factors are most relevant to the assessment of work ability of employees on long-term sick leave? The physicians' perspective. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(5):509–518.

Brongers KA, Cornelius B, Roelofs PDDM, van der Klink JJL, Brouwer S. Feasibility of family group conference to promote return-to-work of persons receiving work disability benefit. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;16:1–10.

Cronin S, Curran J, Iantorno J, Murphy K, Shaw L, Boutcher N, Knott M. Work capacity assessment and return to work: a scoping review. Work. 2013;44(1):37–55.

Velozo C. Work evaluations: critique of the state of the art of functional assessment of work. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47:203–209.

Duijts SF, Kant I, Swaen GM, van den Brandt PA, Zeegers MP. A meta-analysis of observational studies identifies predictors of sickness absence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(11):1105–1115.

Knardahl S, Johannessen HA, Sterud T, Harma M, Rugulies R, Seitsamo J, Borg V. The contribution from psychological, social, and organizational work factors to risk of disability retirement: a systematic review with meta-analyses. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):176.

Snippen NC, de Vries HJ, van der Burg-Vermeulen SJ, Hagedoorn M, Brouwer S. Influence of significant others on work participation of individuals with chronic diseases: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e021742.

Anner J, Kunz R, Boer WD. Reporting about disability evaluation in European countries. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(10):848–854.

Heerkens Y, Engels J, Kuiper C, Van der Gulden J, Oostendorp R. The use of the ICF to describe work related factors influencing the health of employees. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(17):1060–1066.

Heerkens YF, de Brouwer CPM, Engels JA, van der Gulden JWJ, Kant I. Elaboration of the contextual factors of the ICF for occupational health care. Work. 2017;57(2):187–204.

Hoefsmit N, Houkes I, Nijhuis F. Environmental and personal factors that support early return to work: a qualitative study using the ICF as a framework. Work. 2014;48(2):203–215.

Finger ME, Selb M, De Bie R, Escorpizo R. Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in physiotherapy in multidisciplinary vocational rehabilitation: a case study of low back pain. Physiother Res Int. 2015;20(4):231–241.

Boonen A, Braun J, Horst Bruinsma IE, Huang F, Maksymowych W, Kostanjsek N, Cieza A, Stucki G, Van DH. ASAS/WHO ICF core sets for ankylosing spondylitis (AS): how to classify the impact of AS on functioning and health. Ann Rheumat Dis. 2010;69(1):102–107.

Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, Kullmann L, Stoll T, Kamen L, Kostanjsek N, Walsh N. ICF core sets for chronic widespread pain. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:63–68.

Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, Disler P, Jackel W, van der Linden S, Kostanjsek N, de Bie R. ICF core sets for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2004;44:69–74.

Cieza A, Schwarzkopf S, Sigl T, Stucki G, Melvin J, Stoll T, Woolf A, Kostanjsek N, Walsh N. ICF core sets for osteoporosis. J Rehabil Med. 2004;44:81–86.

Dreinhofer K, Stucki G, Ewert T, Huber E, Ebenbichler G, Gutenbrunner C, Kostanjsek N, Cieza A. ICF core sets for osteoarthritis. J Rehabil Med. 2004;2004:75–80.

Grill E, Zochling J, Stucki G, Mittrach R, Scheuringer M, Liman W, Kostanjsek N, Braun J. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core set for patients with acute arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(2):252–258.

Stucki G, Cieza A, Geyh S, Battistella L, Lloyd J, Symmons D, Kostanjsek N, Schouten J. ICF core sets for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rehabil Med. 2004;44:87–93.

Cieza A, Stucki A, Geyh S, Berteanu M, Quittan M, Simon A, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, Walsh N. ICF core sets for chronic ischaemic heart disease. J Rehabil Med. 2004;44:94–99.

Geyh S, Cieza A, Schouten J, Dickson H, Frommelt P, Omar Z, Kostanjsek N, Ring H, Stucki G. ICF core sets for stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2004;7(44):135–141.

Ruof J, Cieza A, Wolff B, Angst F, Ergeletzis D, Omar Z, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G. ICF core sets for diabetes mellitus. J Rehabil Med. 2004;7(44):100–106.

Stucki A, Daansen P, Fuessl M, Cieza A, Huber E, Atkinson R, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, Ruof J. ICF core sets for obesity. J Rehabil Med. 2004;7(44):107–113.

Stucki A, Stoll T, Cieza A, Weigl M, Giardini A, Wever D, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G. ICF core sets for obstructive pulmonary diseases. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:114–120.

Viehoff PB, Heerkens YF, Van Ravensberg CD, Hidding J, Damstra RJ, Ten Napel H, Neumann HAM. Development of consensus international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) core sets for lymphedema. Lymphology. 2015;48(1):38–50.

Cieza A, Kirchberger I, Biering-Sørensen F, Baumberger M, Charlifue S, Post MW, Campbell R, Kovindha A, Ring H, Sinnott A, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G. ICF core sets for individuals with spinal cord injury in the long-term context. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(4):305–312.

Coenen M, Cieza A, Freeman J, Khan F, Miller D, Weise A, Kesselring J. The development of ICF core sets for multiple sclerosis: results of the international consensus conference. J Neurol. 2011;258(8):1477–1488.

Gradinger F, Cieza A, Stucki A, Michel F, Bentley A, Oksenberg A, Rogers AE, Stucki G, Partinen M. Part 1. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core sets for persons with sleep disorders: results of the consensus process integrating evidence from preparatory studies. Sleep Med. 2011;12(1):92–96.

Khan F, Pallant JF. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health to identify preliminary comprehensive and brief core sets for Guillain Barre syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(15–16):1306–1313.

Laxe S, Zasler N, Selb M, Tate R, Tormos JM, Bernabeu M. Development of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core sets for traumatic brain injury: an international consensus process. Brain Inj. 2013;27(4):379–387.

Ayuso-Mateos JL, Avila CC, Anaya C, Cieza A, Vieta E. Development of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core sets for bipolar disorders: results of an international consensus process. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(25):2138–2146.

Bruett AL, Schulz H, Andreas S. Development of an ICF-based core set of activities and participation for patients with mental disorders: an approach based upon data. Clinical Rehabil. 2013;27(8):758–767.

Cieza A, Chatterji S, Andersen C, Cantista P, Herceg M, Melvin J, Stucki G, de Bie R. ICF core sets for depression. J Rehabil Med. 2004;44:128–134.

Gomez-Benito J, Guilera G, Barrios M, Rojo E, Pino O, Gorostiaga A, Balluerka N, Hidalgo MD, Padilla JL, Benitez I, Selb M. Beyond diagnosis: The core sets for persons with schizophrenia based on the world health organization's international classification of functioning, disability, and health. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;30:1–11.

Brach M, Cieza A, Stucki G, Füssl M, Cole A, Ellerin B, Fialka-Moser V, Kostanjsek N, Melvin J. ICF core sets for breast cancer. J Rehabil Med. 2004;07(44):121–127.

Geerse OP, Wynia K, Kruijer M, Schotsman MJ, Hiltermann TJN, Berendsen AJ. Health-related problems in adult cancer survivors: development and validation of the cancer survivor core set. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:567.

Tschiesner U, Rogers S, Dietz A, Yueh B, Cieza A. Development of ICF core sets for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32(2):210–220.

Bölte S, Mahdi S, Coghill D, Gau SS, Granlund M, Holtmann M, Karande S, Levy F, Rohde LA, Segerer W, de Vries PJ, Selb M. Standardised assessment of functioning in ADHD: consensus on the ICF core sets for ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;12:1139.

Bölte S, Mahdi S, de Vries PJ, Granlund M, Robison JE, Shulman C, Swedo S, Tonge B, Wong V, Zwaigenbaum L, Segerer W, Selb M. The gestalt of functioning in autism spectrum disorder: Results of the international conference to develop final consensus international classification of functioning, disability and health core sets. Autism. 2018;23:449.

Danermark B, Granberg S, Kramer SE, Selb M, Möller C. The creation of a comprehensive and a brief core set for hearing loss using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Am J Audiol. 2013;10:4.

Grill E, Bronstein A, Furman J, Zee DS, Müller M. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core set for patients with vertigo, dizziness and balance disorders. J Vestib Res. 2012;22(5–6):261–271.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, Coenen M, Chowers Y, Hibi T, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, Colombel JF. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Gut. 2012;61(2):241–247.

Rudolf KD, Kus S, Chung KC, Johnston M, LeBlanc M, Cieza A. Development of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core sets for hand conditions-results of the world health organization international consensus process. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(8):681–693.

Brage S, Donceel P, Falez F. Development of ICF core set for disability evaluation in social security. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(18):1392–1396.

Finger ME, Escorpizo R, Glässel A, Gmünder HP, Lückenkemper M, Chan C, Fritz J, Studer U, Ekholm J, Kostanjsek N. ICF core set for vocational rehabilitation: results of an international consensus conference. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(5):429–438.

Slebus FG, et al. Work-ability evaluation: a piece of cake or a hard nut to crack? Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(16):1295–1300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Johan H. Sengers, Femke I. Abma, Loes Wilming, Pepijn D.D.M. Roelofs, Yvonne F. Heerkens, and Sandra Brouwer declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sengers, J.H., Abma, F.I., Wilming, L. et al. Content Validation of a Practice-Based Work Capacity Assessment Instrument Using ICF Core Sets. J Occup Rehabil 31, 293–315 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09918-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09918-7