Abstract

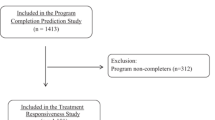

Purpose To determine how the economy affects psychosocial and socioeconomic treatment outcomes in a cohort of chronic disabling occupational musculoskeletal disorder (CDOMD) patients who completed a functional restoration program (FRP). Methods A cohort of 969 CDOMD patients with active workers’ compensation claims completed an FRP (a medically-supervised, quantitatively-directed exercise progression program, with multi-modal disability management). A good economy (GE) group (n = 532) was released to work during a low unemployment period (2005–2007), and a poor economy (PE) group (n = 437) was released during a higher unemployment period (2008–2010). Patients were evaluated upon admission for demographic and psychosocial variables, and were reassessed at discharge. Socioeconomic outcomes, including work return and work retention 1 year post-discharge, were collected. Results Some significant differences in psychosocial self-report data were found, but most of the effect sizes were small, so caution should be made when interpreting the data. Compared to the PE group, the GE group reported more depressive symptoms and disability at admission, but demonstrated a larger decrease in depressive symptoms and disability and increase in self-reported quality of life at discharge. The PE group had lower rates of work return and retention 1-year after discharge, even after controlling for other factors such as length of disability and admission work status. Conclusions CDOMD patients who completed an FRP in a PE year were less likely to return to, or retain, work 1-year after discharge, demonstrating that a PE can be an additional barrier to post-discharge work outcomes. A difference in State unemployment rates of <3 % (7 vs. 5 %) had a disproportionate effect on patients’ failure to return to (19 vs. 6 %) or retain (28 vs. 15 %) work.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Infante-Rivard C, Lortie M. Prognostic factors for return to work after a first compensated episode of back pain. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53(7):488–94.

Jordan KD, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. Should extended disability be an exclusion criterion for tertiary rehabilitation? socioeconomic outcomes of early versus late functional restoration in compensation spinal disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23(19):2110–6.

Anderson PA, Schwaegler PE, Cizek D, Leverson G. Work status as a predictor of surgical outcome of discogenic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(21):2510–5.

Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Frémont P, Rossignol M, Stock SR, Nouwen A, et al. Determinants of “return to work in good health” among workers with back pain who consult in primary care settings: a 2-year prospective study. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(5):641–55.

Fey SG, Williamson-Kirkland TE, Frangione R. In: Vocational restoration in injured workers with chronic pain. Pain; 1987.

Jamison RN, Matt DA, Parris WC. Treatment outcome in low back pain patients: do compensation benefits make a difference? Orthop Rev. 1988;17(12):1210–5.

Straaton KV, Maisiak R, Wrigley JM, Fine PR. Musculoskeletal disability, employment, and rehabilitation. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(3):505–13.

Anagnostis C, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, Proctor T. The million visual analog scale: its utility for predicting tertiary rehabilitation outcomes. Spine. 2003;28:1051–60.

Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG, Kidner CL, McGeary DD. Are gender, marital status or parenthood risk factors for outcome of treatment for chronic disabling spinal disorders? J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(2):191–201.

Campello MA, Weiser SR, Nordin M, Hiebert R. Work retention and nonspecific low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(16):1850–7.

Srivastava S, Chamberlain A. Factors determining job retention and return to work for disabled employees: a questionnaire study of opinions of disabled people’s organizations in the UK. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(1):17–22.

Viikari-Juntura E, Burdorf A. Return to work and job retention–increasingly important outcomes in occupational health research. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(2):81–4.

Wu J, Chen Y, Liu L, Chen T, Huang W, Cheng H, et al. Effects of age, gender, and socio-economic status on the incidence of spinal cord injury: an assessment using the eleven-year comprehensive nationwide database of taiwan. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(5):889–97.

Pentland W, McColl MA, Rosenthal C. The effect of aging and duration of disability on long term health outcomes following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1995;33(7):367–73.

Tausig M, Fenwick R. Work and mental health in social context. New York: Springer; 2011.

US business cycle expansions and contractions [homepage on the Internet]. 2012. Available from. http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Economic news release: persons with a disability: Barriers to employment, type of assistance, and other labor-related issues summary. 2013.

Zurich American Insurance Company. Recession, recovery and workers’ compensation claims. 2010.

National Academy of Social Insurance. Press release: Workers’ compensation benefits, employer costs rise wth economic recovery. 2013.

Datta DK, Guthrie JP, Basuil D, Pandey A. Causes and effects of employee downsizing: a review and synthesis. J Manag. 2010;36(1):281–348.

Schmidt SR. Long-run trends in workers’ beliefs about their own job security: evidence from the general social survey. J Labor Econ. 1999;17(S4):S127–41.

An analysis of workers who were fired or laid off after a work-related injury Executive summary [homepage on the Internet]. 2013. Available from. http://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/wcreg/fired.html.

Schulman BM. Worklessness and disability: expansion of the biopsychosocial perspective. J Occup Rehabil. 1994;4(2):113–22.

Bartley M, Sacker A, Clarke P. Employment status, employment conditions, and limiting illness: prospective evidence from the British household panel survey 1991–2001. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):501–6.

Danna K, Griffin RW. Health and well-being in the workplace: a review and synthesis of the literature. J Manag. 1999;25(3):357–84.

Kuhnert KW, Palmer DR. Job security, health, and the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of work. Group Org Manag. 1991;16(2):178–92.

Hall AM, Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML, Nicholas MK. Symptoms of depression and stress mediate the effect of pain on disability. Pain. 2011;152(5):1044–51.

Luo X, Edwards CL, Richardson W, Hey L. Relationships of clinical, psychologic, and individual factors with the functional status of neck pain patients. Value Health. 2004;7(1):61–9.

Dersh J, Polatin PB, Leeman G, Gatchel RJ. The management of secondary gain and loss in medicolegal settings: strengths and weaknesses. J Occup Rehabil. 2004;14(4):267–79.

Labor force statistics from the current population survey [homepage on the Internet]. 2013.

Hazard RG, Fenwick JW, Kalisch SM, Redmond J, Reeves V, Reid S, et al. Functional restoration with behavioral support. A one-year prospective study of patients with chronic low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14(2):157–61.

Mayer E, Mayer TG. The interdisciplinary treatment of the patient with chronic pain. In: Rao RD, Smuch M, editors. Orthopedic knowledge update. 4th ed. Chicago: AAOS Press; 2012. p. 169–80.

Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, Mayer H, Kishino ND, Keeley J, Mooney V. A prospective two-year study of functional restoration in industrial low back injury. An objective assessment procedure. JAMA. 1987;258(13):1763–7.

Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, Kishino N, Keeley J, Capra P, Mayer H, et al. Objective assessment of spine function following industrial injury: a prospective study with comparison group and one-year follow-up. Spine. 1985;10:482–92.

Capra P, Mayer T, Gatchel R. Adding psychological scales to your low back assessment. J Musculoskelet Med. 1985;7:41–52.

Anagnostis C, Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG. The pain disability questionnaire: a new psychometrically sound measure for chronic musculoskeletal disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(20):2290–302.

Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG, Theodore BR. The pain disability questionnaire: relationship to one-year functional and psychosocial rehabilitation outcomes. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:75–94.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–63.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–71.

Mayer TG, Prescott M, Gatchel RJ. Objective outcomes evaluation: methods and evidence. In: Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, editors. Occupational musculoskeletal disorders: function, outcomes and evidence. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2000. p. 651–67.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data analysis. 6th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2006.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60.

Asklöf T, Kautiainen H, Järvenpää S, Haanpää M, Kiviranta I, Pohjolainen T. Disability pensions due to spinal disorders: nationwide finnish register-based study, 1990–2010. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(6):503–8.

Schofield DJ, Shrestha RN, Percival R, Callander EJ, Kelly SJ, Passey ME. Early retirement and the financial assets of individuals with back problems. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(5):731–6.

Grahn BE, Borgquist LA, Ekdahl CS. Motivated patients are more cost-effectively rehabilitated. A two-year prospective controlled study of patients with prolonged musculoskeletal disorders diagnosed in primary care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(3):849–63.

Grahn BEM, Borgquist LA, Ekdahl CS. Rehabilitation benefits highly motivated patients: a six-year prospective cost-effectiveness study. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(2):214–21.

Lydell M, Hildingh C, Månsson J, Marklund B, Grahn B. Thoughts and feelings of future working life as a predictor of return to work: a combined qualitative and quantitative study of sick-listed persons with musculoskeletal disorders. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(13–14):1262–71.

Wainwright E, Wainwright D, Keogh E, Eccleston C. Return to work with chronic pain: employers’ and employees’ views. Occup Med (Lond). 2013;63(7):501–6.

Langan JC, Tadych RA, Kao C. Exploring incentives for RNs to return to practice: a partial solution to the nursing shortage. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23(1):13–20.

Doiron D, Mendolia S. The impact of job loss on family dissolution. J Popul Econ. 2012;25(1):367–98.

Conflict of interest

Meredith M. Hartzell, Tom G. Mayer, Randy Neblett, Robert J. Gatchel, and Dennis Marquardt declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hartzell, M.M., Mayer, T.G., Neblett, R. et al. Does the Economy Affect Functional Restoration Outcomes for Patients with Chronic Disabling Occupational Musculoskeletal Disorders?. J Occup Rehabil 25, 378–386 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9546-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9546-1