Abstract

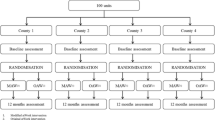

Introduction Evidence suggests that supervisors’ behaviors have a strong influence on employees’ health and well-being outcomes. Few have examined the specific behaviors associated with managing an employee back to work following long-term sick leave. This study describes the development of a behavior measure for Supervisors to Support Return to Work (SSRW) using qualitative and quantitative research methods. Methods Qualitative data were collected between 2008 and 2010 from a UK population of organisational stakeholders (N = 142), line managers (N = 20) and employees (N = 26). Data from these samples were used to develop a 42 item questionnaire and to validate it using a further sample of line managers (N = 186) and employees (N = 359). Results Based on a factor structure and reliability results, four scales emerged. The measure demonstrated good internal reliability, construct and concurrent validity. Longitudinal data analyses demonstrated test–retest reliability and promising predictive validity. Conclusions This is a potentially valuable tool in research and in organisational settings, both during long-term sick leave and after employees have returned to work.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Health Safety Executive self-report work-related illness. 2003/2004. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics.

Henderson M, Glozier N, Elliot KH. Long term sickness absence. BMJ. 2005;330:802–3.

Pryce J, Munir F, Haslam C. Cancer survivorship and work: symptoms, supervisor response, co-workers’ disclosure and work adjustments. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:83–92.

Escriba-Aguir V, Perez-Hoyos S. Psychological well-being and psychosocial work environment characteristics among emergency and medical staff. Stress Health. 2007;23:153–60.

Skakon J, Nielsen K, Borg V, Guzman J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviors and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress. 2010;24:107–39.

Baruch-Feldman C, Brondolo E, Ben-Dayan D, Schwartz J. Sources of social support and burnout, job satisfaction and productivity. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7:84–93.

Stansfeld SA, Rael GS, Head J, Shipley M, Marmot M. Social support and psychiatric sickness absence: a prospective study of British Civil Servants. Psychol Med. 1997;27:35–48.

Netterstrom B, Conrad N, Bech P, Fink P, Olsen O, Rugulies R, Stansfeld S. The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:118–32.

Thomas LT, Ganster DC. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Appl Psychol. 1995;80:6–15.

Bass BM. Bass Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: theory, research, and managerial applications. 3rd ed. New York: Free Press; 1990.

Nielsen ML, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Smith-Hansen L, Kristensen TS. Psychosocial work environment predictors of short and long spells of registered sickness absence during a 2-year follow up. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:591–8.

Väänänen A, Toppinen-Tanner S, Kalimo R, Mutanen P, Vahtera J, Peiro JM. Job characteristics, physical and psychological symptoms, and social support as antecedents of sickness absence among men and women in the private industrial sector. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:807–24.

Labriola M, Lund T, Burr H. Prospective study of physical and psychosocial risk factors for sickness absence. Occup Med. 2006;56:469–74.

Saksvik PO, Nytro K, Dahl-Jorgensen C, Mikkelsen A. A process evaluation of individual and organisational occupational stress and health interventions. Work Stress. 2002;16:37–57.

Rick J, Thompson L. Managers’ roles in rehabilitation for work-related stress. In: Proceedings of the division of occupational psychology conference. British Psychological Society, UK, 2004.

Bevan S. Attendance management. London: The Work Foundation; 2003.

Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London: The Stationary office; 2008.

Holmgren K, Ivanoff SD. Supervisors views on employer responsibility in the return to work process. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:93–106.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JHAM, De Boer AGEM, Blonk RWB, Van Djik FJH. Supervisory behavior as a predictor of return to work in employee absent from work due mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2006;61:817–23.

Ashby K, Mahdon M. Why do employees come to work when ill? An investigation into sickness presence in the workplace. London: The Work Foundation; 2010.

Pransky J, Shaw W, Loisel P, Hong QN, Desorcy B. Development and validation of competencies for return-to-work coordinators. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:41–8.

Aas RW, Ellingsen KJ, Lindøe P, Möller A. Leadership qualities in the return to work process: A content analysis. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:335–46.

Wynne-Jones G, Buck R, Porteous C, Cooper L, Button LA, Main CJ, Phillips CJ. What happens to work if you are unwell? Beliefs and attitudes of managers and employees with musculoskeletal pain in a public sector setting. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;1:31–42.

Rankin I. Managing long-term sickness absence: the 2009 IRS survey. IRS Employ Rev. 2009;992:1–18.

Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull. 1954;51:327–58.

Miles MB, Huberman MA. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Dasborough MT. Cognitive asymmetry in employee emotional reactions to leadership behaviors. Lead Q. 2009;17:163–78.

Donald I. Facet theory: defining research domains. In: Breakwell GM, Hammond S, Fife-Shaw C, et al., editors. Research methods in psychology. London: Sage; 1995.

Coolican H. Research methods and statistics in psychology. London: Hodder and Staughton; 1994.

Goldberg D. GHQ-12. London: NFER-Nelson; 1978.

Gillbreath B, Benson PG. The contribution of supervisor behavior to employee psychological well-being. Work Stress. 2004;18:255–66.

Nagy MS. Using a single-time approach to measure facet job satisfaction. J Occup Org Psychol. 2002;75:77–86.

Wanous JP, Reichers AE, Hudy MJ. Overall job satisfaction: How good are single item measures? J App Psychol. 1997;82:247–52.

Stewart A, Ware J. Measuring functioning and wellbeing: the medical outcomes approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. p. 373–403.

Lerner D, Amick B III. Glaxo welcome. Work limitations questionnaire. Boston: The Health Institute. Tufts-New England Medical Center; 1998.

Bond FW, Bunce D. Job control mediates change in a work reorganization intervention for stress reduction. J Occup Health Psychol. 2001;6:290–302.

Ferguson E, Cox T. Exploratory factor analysis: a user’s guide. Int J Select Assess. 1993;1:84–94.

Nunnally JC. Psychometric methods. New York: McGraw Hill; 1967.

Van Horn JE, Taris T, Schaufeli WB, Schreurs PA. The structure of occupational well-being: a study among Dutch teachers. J Occup Org Psychol. 2004;77:365–77.

Franche R-L, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of healthcare, workplace and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12:233–56.

MacKenzie EJ, Morris JA, Jurkovich GJ, Yasui Y, Cushing BM, Burgess AR, DeLateur BJ, McAndrew MP, Swiontkowski MF. Return to work following injury: the role of economic, social and job-related factors. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1630–7.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participating organisations and stakeholders for their support. We would also like to thank the line managers and employees who took part. This research was funded by the British Occupational Health Research Foundation (BOHRF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Munir, F., Yarker, J., Hicks, B. et al. Returning Employees Back to Work: Developing a Measure for Supervisors to Support Return to Work (SSRW). J Occup Rehabil 22, 196–208 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9331-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9331-3