Abstract

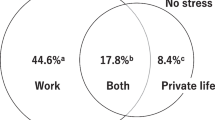

Introduction Work-related injuries or disabilities result in significant negative consequences to physical, economic, social, and psychological well-being. Depression has been shown to increase post-injury and to contribute to poor return to work outcomes. The primary goals of the study were to test known correlates of depression in a sample of injured workers receiving vocational rehabilitation and to assess the unique contribution of work values in injured worker depression. Method Scores on depression, stress, pain, work values, and demographic information were obtained from an archived sample of 253 injured workers receiving vocational rehabilitation. Results Hierarchical multiple linear regression was used for analyses, resulting in a final model with a “large” effect size (R 2 = 0.42). The accepting vs. investigative work value dimension accounted for variance in depression scores beyond that accounted for by covariates and other significant correlates. Of the study variables, significant regression coefficients were found for pain, psychosocial stress, an interaction between pain and stress, and having an accepting work value. Conclusions Injured workers experiencing higher levels of pain and stress and who prefer to avoid workplace challenges may be vulnerable to experiencing depression. Results suggest that the presence of pain, stress, and the accepting work value dimension should be monitored in injured workers, and that the role of work values in injured worker depression may be a fruitful area for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Waldrop J, Stern SM. Disability status: 2000 (Report No. C2KBR-17). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2003.

National Safety Council. Injury facts: 2005–2006 edition. Itasca, IL: National Safety Council; 2006.

Dersh J, Gatchel RJ, Polatin P, Mayer T. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic work-related musculoskeletal pain disability. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(5):459–68.

Keogh JP, Nuwayhid I, Gordon JL, Gucer P. The impact of occupational injury on injured worker and family: outcomes of upper extremity cumulative trauma disorders in Maryland workers. Am J Ind Med. 2000;38:498–506.

Fierro RJ, Leal A. Psychological effects of early versus late referral to the vocational rehabilitation process: the case of Mexican origin industrially injured workers. J Appl Rehabil Couns. 1988;19(4):35–9.

Seff MA, Gecas V, Ray MP. Injury and depression: the mediating effects of self-concept. Soc Perspect. 1992;35(4):573–91.

Stice DC, Moore CL. A study of the relationship of the characteristics of injured workers receiving vocational rehabilitation services and their depression levels. J Rehabil. 2005;71(4):12–22.

Mason S, Wardrope J, Turpin G, Rowlands A. Outcomes after injury: a comparison of workplace and nonworkplace injury. J Trauma. 2002;53(1):98–103.

Fishbain DA, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:116–37.

Campbell LC, Clauw DJ, Keefe FJ. Persistent pain and depression: a biopsychosocial perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):399–409.

Hitchcock LS, Ferrell BR, McCaffery M. The experience of chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1994;9(5):312–8.

Geisser ME, Roth RS, Theisen ME, Robinson ME, Riley JL. Negative affect, self-report of depressive symptoms, and clinical depression: relation to the experience of chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(2):110–20.

Lötters F, Franche R-L, Hogg-Johnson S, Burdorf A, Pole JD. The prognostic value of depressive symptoms, fear-avoidance, and self-efficacy for duration of lost-time benefits in workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:794–801.

Corbière M, Sullivan MJL, Stanish WD, Adams H. Pain and depression in injured workers and their return to work: a longitudinal study. Can J Behav Sci. 2007;39(1):23–31.

Sullivan MJL, Adams H, Tripp D, Stanish WD. Stage of chronicity and treatment response in patients with musculoskeletal injuries and concurrent symptoms of depression. Pain. 2008;135:151–9.

McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: an examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2003;106:127–33.

Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(1):95–110.

Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Côté P. Depression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back pain. Pain. 2004;107:134–9.

Morse TF, Dillon C, Warren N, Levenstein C, Warren A. The economic and social consequences of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: the Connecticut Upper-Extremity Surveillance Project (CUSP). Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4(4):209–16.

Asmundson GJ, Norton GR, Allerdings MD, Norton PJ, Larsen DK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and work-related injury. J Anxiety Disord. 1998;12(1):57–69.

Kirsh B, McKee P. The needs and experiences of injured workers: a participatory research study. Work. 2003;21:221–31.

Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:191–214.

Grant I, Sweetwood HL, Yager J, Gerst MS. Patterns in the relationship of life events and psychiatric symptoms over time. J Psychosom Res. 1978;22:183–91.

Rahe RH. Life change events and mental illness: an overview. J Human Stress. 1979;5(3):2–10.

Zimmerman M, O’Hara MW, Corenthal CP. Symptom communication of life event scales. Health Psychol. 1984;3(1):77–81.

Dooley D, Catalano R, Wilson G. Depression and unemployment: panel findings from the epidemiological catchment area study. Am J Community Psychol. 1994;22(6):745–65.

Turner JB, Turner RJ. Physical disability, unemployment, and mental health. Rehabil Psychol. 2003;49(3):241–9.

Peteet JR. Cancer and the meaning of work. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:200–5.

Bleuler M. Conception of schizophrenia within the last fifty years and today. Proc R Soc Med. 1963;56:945–52.

Brown GW, Harris TO. Social origins of depression: a study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: Free Press; 1978.

Beck AT. Cognitive models of depression. J Cogn Psychother. 1987;1:5–38.

Dawis RV, Lofquist LH. A psychological theory of work adjustment. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1984.

Knapp L, Knapp-Lee L. COPES examiner’s manual. San Diego, CA: EdITS; 1996.

Barnett PA, Gotlib IH. Psychosocial functioning and depression: distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychol Bull. 1988;104(1):97–126.

Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. Personality traits and the development of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation. Pers Individ Differ. 2005;38(6):1283–91.

Ash P, Goldstein SI. Predictors of returning to work. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):205–10.

Sullivan MJL, Adams H, Thibault P, Corbière M, Stanish WD. Initial depression severity and the trajectory of recovery following cognitive-behavioral intervention for work disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(1):63–74.

Vowles KE, Gross RT, Sorrell JT. Predicting work status following interdisciplinary treatment for chronic pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):351–8.

Falvo DR. Medical and psychosocial aspects of chronic illness and disability. 3rd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2005.

US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. Dictionary of occupational titles. 4th ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration; 1991.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck depression inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–8.

Scully JA, Tosi H, Banning K. Life event checklists: revisiting the social readjustment rating scale after 30 years. Educ Psychol Meas. 2000;60(6):864–76.

Thurlow HJ. Illness in relation to life situation and sick-role tendency. J Psychosom Res. 1971;15:73–88.

Bieliauskas LA, Strugar DA. Sample size characteristics and scores on the social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1976;20:201–5.

Costantini AF, Braun JR, Davis J, Iervolino A. The life change inventory: a device for quantifying psychological magnitude of changes experienced by college students. Psychol Rep. 1974;34:991–1000.

Gerst MS, Grant I, Yager J, Sweetwood H. The reliability of the social readjustment rating scale: moderate and long-term stability. J Psychosom Res. 1978;22:519–623.

Aponte JF, Miller FT. Stress-related social events and psychological impairment. J Clin Psychol. 1972;28(4):455–8.

Rahe RH, Arthur RJ. Life change and illness studies: past history and future directions. J Human Stress. 1978;4(1):3–15.

Theorell T. Life events before and after the onset of a premature myocardial infarction. In: Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, editors. Stressful live events: their nature and effects. New York: Wiley; 1974. p. 101–17.

Melzack R. The short-form McGill pain questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191–7.

Dudgeon D, Raubertas RF, Rosenthal SN. The short-form McGill pain questionnaire in chronic cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1993;8(4):191–5.

Zalon ML. Comparison of pain measures in surgical patients. J Nurs Manag. 1999;7(2):135–52.

Melzack R, Katz J. The McGill pain questionnaire: appraisal and current status. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. New York: Guilford; 2001. p. 35–52.

Grafton KV, Foster NE, Wright CC. Test-retest reliability of the short-form McGill pain questionnaire: assessment of intraclass correlation coefficients and limits of agreement in patients with osteoarthritis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(1):73–82.

Knapp-Lee LJ. Use of the COPES, a measure of work values, in career assessment. J Career Assess. 1996;4(4):429–43.

Knapp L, Michael WB. Relationship of work values to corresponding academic success. Educ Psychol Meas. 1980;40:487–94.

Tinsley HEA, Brown SD. Multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. In: Tinsley HEA, Brown SD, editors. Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. p. 3–36.

Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51(1):115–34.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

McCracken LM. Learning to live with the pain: acceptance of pain predicts adjustment in persons with chronic pain. Pain. 1998;74:21–7.

Livneh H, Antonak RF. Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1997.

Seligman MEP. Helplessness: on depression, development, and death. 2nd ed. New York: WH Freeman; 1991.

Abramson LY, Seligman MEP, Teasdale I. Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978;87:49–59.

Rudy TE, Kerns RD, Turk DC. Chronic pain and depression: toward a cognitive-behavioral mediation model. Pain. 1988;35(2):129–40.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford; 1991.

Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986.

Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Collins JF, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971–83.

Thase ME, Kupfer DJ. Recent developments in the pharmacotherapy of mood disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(4):646–59.

Rounds JB, Henley GA, Dawis RV, Lofquist LH, Weiss DJ. Manual for the Minnesota importance questionnaire: a measure of needs and values. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1981.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-fast screen for medical patients: manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly thank Dennis C. Stice, PhD for the use of his data in conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stice, B.D., Dik, B.J. Depression Among Injured Workers Receiving Vocational Rehabilitation: Contributions of Work Values, Pain, and Stress. J Occup Rehabil 19, 354–363 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9190-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9190-3