Abstract

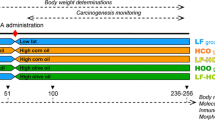

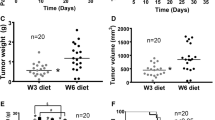

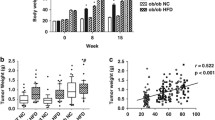

Studies in rodents have shown that dietary modifications as mammary glands (MG) develop, regulates susceptibility to mammary tumor initiation. However, the effects of dietary PUFA composition on MGs in adult life, remains poorly understood. This study investigated morphological alterations and inflammatory microenvironments in the MGs of adult mice fed isocaloric and isolipidic liquid diets with varying compositions of omega (ω)-6 and long-chain (Lc)-ω3FA that were pair-fed. Despite similar consumption levels of the diets, mice fed the ω-3 diet had significantly lower body-weight gains, and abdominal-fat and mammary fat pad (MFP) weights. Fatty acid analysis showed significantly higher levels of Lc-ω-3FAs in the MFPs of mice on the ω-3 diet, while in the MFPs from the ω-6 group, Lc-ω-3FAs were undetectable. Our study revealed that MGs from ω-3 group had a significantly lower ductal end-point density, branching density, an absence of ductal sprouts, a thinner ductal stroma, fewer proliferating epithelial cells and a lower transcription levels of estrogen receptor 1 and amphiregulin. An analysis of the MFP and abdominal-fat showed significantly smaller adipocytes in the ω-3 group, which was accompanied by lower transcription levels of leptin, IGF1, and IGF1R. Further, MFPs from the ω-3 group had significantly decreased numbers and sizes of crown-like-structures (CLS), F4/80+ macrophages and decreased expression of proinflammatory mediators including Ptgs2, IL6, CCL2, TNFα, NFκB, and IFNγ. Together, these results support dietary Lc-ω-3FA regulation of MG structure and density and adipose tissue inflammation with the potential for dietary Lc-ω-3FA to decrease the risk of mammary gland tumor formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Arachidonic acid

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA:

-

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- FA:

-

Fatty acid

- IGF:

-

Insulin like growth factor

- Lc:

-

Long-chain

- MFP:

-

Mammary fat pad

- MG:

-

Mammary gland

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SFA:

-

Saturated Fatty Acid

- SPF:

-

Specific pathogen free

- TEB:

-

Terminal end bud

References

Olson LK, Tan Y, Zhao Y, Aupperlee MD, Haslam SZ. Pubertal exposure to high fat diet causes mouse strain-dependent alterations in mammary gland development and estrogen responsiveness. Int J Obes. 2010;34(9):1415–26.

Fasano E, et al. Long-chain n-3 PUFA against breast and prostate cancer: which are the appropriate doses for intervention studies in animals and humans? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;57(11):2245–62.

Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R, Onojafe I, Raygada M, Cho E, Lippman M. A maternal diet high in n - 6 polyunsaturated fats alters mammary gland development, puberty onset, and breast cancer risk among female rat offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(17):9372–7.

Hilakivi-Clarke L, Olivo SE, Shajahan A, Khan G, Zhu Y, Zwart A, et al. Mechanisms mediating the effects of prepubertal (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid diet on breast cancer risk in rats. J Nutr. 2005;135(12 Suppl):2946S–52S.

MacLennan MB, Anderson BM, Ma DW. Differential mammary gland development in FVB and C57Bl/6 mice: implications for breast cancer research. Nutrients. 2011;3(11):929–36.

Anderson BM, MacLennan MB, Hillyer LM, Ma DWL. Lifelong exposure to n-3 PUFA affects pubertal mammary gland development. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(6):699–706.

Zhu Z, Jiang W, McGinley JN, Prokopczyk B, Richie JP, el Bayoumy K, et al. Mammary gland density predicts the cancer inhibitory activity of the N-3 to N-6 ratio of dietary fat. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(10):1675–85.

Hilakivi-Clarke L. Nutritional modulation of terminal end buds: its relevance to breast cancer prevention. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7(5):465–74.

Davis CD, Uthus EO. DNA methylation, cancer susceptibility, and nutrient interactions. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2004;229(10):988–95.

Maller O, Martinson H, Schedin P. Extracellular matrix composition reveals complex and dynamic stromal-epithelial interactions in the mammary gland. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(3):301–18.

Iyengar NM, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Obesity and inflammation: new insights into breast cancer development and progression. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013;33:46–51.

Hovey RC, Aimo L. Diverse and active roles for adipocytes during mammary gland growth and function. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(3):279–90.

Berger NA. Crown-like structures in breast adipose tissue from normal weight women: important impact. Cancer Prev Res. 2017;10(4):223–5.

Couldrey C, Moitra J, Vinson C, Anver M, Nagashima K, Green J. Adipose tissue: a vital in vivo role in mammary gland development but not differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2002;223(4):459–68.

MacLennan M, Ma DW. Role of dietary fatty acids in mammary gland development and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(5):211.

Olivo SE, Hilakivi-Clarke L. Opposing effects of prepubertal low- and high-fat n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diets on rat mammary tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(9):1563–72.

Khadge S, Sharp JG, Thiele GM, McGuire TR, Klassen LW, Duryee MJ, et al. Dietary omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids modulate hepatic pathology. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;52:92–102.

Sealls W, Gonzalez M, Brosnan MJ, Black PN, DiRusso CC. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids (C18:2 omega6 and C18:3 omega3) do not suppress hepatic lipogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781(8):406–14.

Gonzalez M, Sealls W, Jesch ED, Brosnan MJ, Ladunga I, Ding X, et al. Defining a relationship between dietary fatty acids and the cytochrome P450 system in a mouse model of fatty liver disease. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43(3):121–35.

Blacher S, Gérard C, Gallez A, Foidart JM, Noël A, Péqueux C. Quantitative assessment of mouse mammary gland morphology using automated digital image processing and TEB detection. Endocrinology. 2016;157(4):1709–16.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8.

Belzung F, Raclot T, Groscolas R. Fish oil n-3 fatty acids selectively limit the hypertrophy of abdominal fat depots in growing rats fed high-fat diets. Am J Phys. 1993;264(6 Pt 2):R1111–8.

Peyron-Caso E, Quignard-Boulangé A, Laromiguière M, Feing-Kwong-Chan S, Véronèse A, Ardouin B, et al. Dietary fish oil increases lipid mobilization but does not decrease lipid storage-related enzyme activities in adipose tissue of insulin-resistant, sucrose-fed rats. J Nutr. 2003;133(7):2239–43.

Casado-Diaz A, et al. The omega-6 arachidonic fatty acid, but not the omega-3 fatty acids, inhibits osteoblastogenesis and induces adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells: potential implication in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(5):1647–61.

Massaro M, Habib A, Lubrano L, Turco SD, Lazzerini G, Bourcier T, et al. The omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoate attenuates endothelial cyclooxygenase-2 induction through both NADP(H) oxidase and PKC epsilon inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(41):15184–9.

Ukropec J, Reseland JE, Gasperikova D, Demcakova E, Madsen L, Berge RK, et al. The hypotriglyceridemic effect of dietary n-3 FA is associated with increased beta-oxidation and reduced leptin expression. Lipids. 2003;38(10):1023–9.

Wójcik C, Lohe K, Kuang C, Xiao Y, Jouni Z, Poels E. Modulation of adipocyte differentiation by omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids involves the ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18(4):590–9.

Brenna JT. Efficiency of conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to long chain n-3 fatty acids in man. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5(2):127–32.

Zhu ZR, Ågren J, Männistö S, Pietinen P, Eskelinen M, Syrjänen K, et al. Fatty acid composition of breast adipose tissue in breast cancer patients and in patients with benign breast disease. Nutr Cancer. 1995;24(2):151–60.

Bagga D, Anders KH, Wang HJ, Glaspy JA. Long-chain n-3-to-n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratios in breast adipose tissue from women with and without breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2002;42(2):180–5.

Palomer X, et al. Palmitic and Oleic Acid: The Yin and Yang of Fatty Acids in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 29(3):178–90.

Hilakivi-Clarke L, Stoica A, Raygada M, Martin MB. Consumption of a high-fat diet alters estrogen receptor content, protein kinase C activity, and mammary gland morphology in virgin and pregnant mice and female offspring. Cancer Res. 1998;58(4):654–60.

Hilakivi-Clarke L, Cho E, Cabanes A, DeAssis S, Olivo S, Helferich W, et al. Dietary modulation of pregnancy estrogen levels and breast cancer risk among female rat offspring. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(11):3601–10.

McGinley JN, Thompson HJ. Quantitative assessment of mammary gland density in rodents using digital image analysis. Biol Proced Online. 2011;13(1):4.

McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast Cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(6):1159–69.

Sandhu, N., Schetter S.E., Liao J., Hartman T.J., Richie J.P., McGinley J., Thompson H.J., Prokopczyk B., DuBrock C., Signori C., Hamilton C., Calcagnotto A., Trushin N., Aliaga C., Demers L.M., El-Bayoumy K., Manni A., Influence of obesity on breast density reduction by omega-3 fatty acids: evidence from a randomized clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res, April 1 2016 (9) (4) 275–282.

Wolfson B, et al. A high-fat diet promotes mammary gland Myofibroblast differentiation through MicroRNA 140 downregulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2017;37(4):e00461–16.

Xue L, Newmark H, Yang K, Lipkin M. Model of mouse mammary gland hyperproliferation and hyperplasia induced by a western-style diet. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26(3):281–7.

Hidaka BH, Li S, Harvey KE, Carlson SE, Sullivan DK, Kimler BF, et al. Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids in blood and breast tissue of high-risk women and association with atypical Cytomorphology. Cancer Prev Res. 2015;8(5):359–64.

Fabian CJ, et al. Modulation of Breast Cancer Risk Biomarkers by High Dose Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Phase II Pilot Study in Pre-menopausal Women. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2015;8(10):922–31.

Yee LD, et al. The inhibition of early stages of HER-2/neu-mediated mammary carcinogenesis by dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(2) https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200445.

Manni A, Richie JP Jr, Xu H, Washington S, Aliaga C, Bruggeman R, et al. Influence of omega-3 fatty acids on tamoxifen-induced suppression of rat mammary carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(7):1549–57.

Cunha GR, Young P, Hom YK, Cooke PS, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB. Elucidation of a role for stromal steroid hormone receptors in mammary gland growth and development using tissue recombinants. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1997;2(4):393–402.

Mueller SO, Clark JA, Myers PH, Korach KS. Mammary gland development in adult mice requires epithelial and stromal estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrinology. 2002;143(6):2357–65.

Ciarloni L, Mallepell S, Brisken C. Amphiregulin is an essential mediator of estrogen receptor α function in mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(13):5455–60.

Kenney NJ, Smith GH, Rosenberg K, Cutler ML, Dickson RB. Induction of ductal morphogenesis and lobular hyperplasia by amphiregulin in the mouse mammary gland. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7(12):1769–81.

Ruan W, Monaco ME, Kleinberg DL. Progesterone stimulates mammary gland ductal morphogenesis by synergizing with and enhancing insulin-like growth factor-I action. Endocrinology. 2005;146(3):1170–8.

Hadsell DL, Bonnette SG. IGF and insulin action in the mammary gland: lessons from transgenic and knockout models. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000;5(1):19–30.

Drolet R, Richard C, Sniderman AD, Mailloux J, Fortier M, Huot C, et al. Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of abdominal adipose tissues in women. Int J Obes. 2008;32(2):283–91.

LeMieux MJ, Kalupahana NS, Scoggin S, Moustaid-Moussa N. Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces adipocyte hypertrophy and inflammation in diet-induced obese mice in an adiposity-independent manner. J Nutr. 2015;145(3):411–7.

Obst BE, Schemmel RA, Czajka-Narins D, Merkel R. Adipocyte size and number in dietary obesity resistant and susceptible rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1981;240(1):E47–53.

Haramizu S, Nagasawa A, Ota N, Hase T, Tokimitsu I, Murase T. Different contribution of muscle and liver lipid metabolism to endurance capacity and obesity susceptibility of mice. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;106(3):871–9.

Buckley JD, Howe PRC. Long-chain Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may be beneficial for reducing obesity—a review. Nutrients. 2010;2(12):1212–30.

Mori T, Kondo H, Hase T, Tokimitsu I, Murase T. Dietary fish oil upregulates intestinal lipid metabolism and reduces body weight gain in C57BL/6J mice. J Nutr. 2007;137(12):2629–34.

Flachs P, Horakova O, Brauner P, Rossmeisl M, Pecina P, Franssen-van Hal N, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine origin upregulate mitochondrial biogenesis and induce beta-oxidation in white fat. Diabetologia. 2005;48(11):2365–75.

Ailhaud G, et al. Temporal changes in dietary fats: role of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in excessive adipose tissue development and relationship to obesity. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45(3):203–36.

Massiera F, Barbry P, Guesnet P, Joly A, Luquet S, Moreilhon-Brest C, et al. A western-like fat diet is sufficient to induce a gradual enhancement in fat mass over generations. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(8):2352–61.

Gaillard D, Négrel R, Lagarde M, Ailhaud G. Requirement and role of arachidonic acid in the differentiation of pre-adipose cells. Biochem J. 1989;257(2):389–97.

Kim HK, Della-Fera MA, Lin J, Baile CA. Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits adipocyte differentiation and induces apoptosis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Nutr. 2006;136(12):2965–9.

Kalupahana NS, Claycombe K, Newman SJ, Stewart T, Siriwardhana N, Matthan N, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid prevents and reverses insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese mice via modulation of adipose tissue inflammation. J Nutr. 2010;140(11):1915–22.

Skurk T, Alberti-Huber C, Herder C, Hauner H. Relationship between adipocyte size and adipokine expression and secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):1023–33.

Frederich RC, Hamann A, Anderson S, Löllmann B, Lowell BB, Flier JS. Leptin levels reflect body lipid content in mice: evidence for diet-induced resistance to leptin action. Nat Med. 1995;1(12):1311–4.

Meilleur KG, Doumatey A, Huang H, Charles B, Chen G, Zhou J, et al. Circulating adiponectin is associated with obesity and serum lipids in west Africans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(7):3517–21.

Meyer LK, Ciaraldi TP, Henry RR, Wittgrove AC, Phillips SA. Adipose tissue depot and cell size dependency of adiponectin synthesis and secretion in human obesity. Adipocytes. 2013;2(4):217–26.

Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395(6704):763–70.

Kim EJ, Choi MR, Park H, Kim M, Hong JE, Lee JY, et al. Dietary fat increases solid tumor growth and metastasis of 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma cells and mortality in obesity-resistant BALB/c mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(4):R78.

Pérez-Matute P, Pérez-Echarri N, Martínez JA, Marti A, Moreno-Aliaga MJ. Eicosapentaenoic acid actions on adiposity and insulin resistance in control and high-fat-fed rats: role of apoptosis, adiponectin and tumour necrosis factor-α. Br J Nutr. 2007;97(2):389–98.

Neschen S, Morino K, Rossbacher JC, Pongratz RL, Cline GW, Sono S, et al. Fish oil regulates adiponectin secretion by a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-dependent mechanism in mice. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):924–8.

Loffreda S, Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Karp CL, Brengman ML, Wang DJ, et al. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J. 1998;12(1):57–65.

Hu X, et al. Leptin--a growth factor in normal and malignant breast cells and for normal mammary gland development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(22):1704–11.

Sjögren K, et al. Liver-derived insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is the principal source of IGF-I in blood but is not required for postnatal body growth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(12):7088–92.

Chang HR, Kim HJ, Xu X, Ferrante AW Jr. Macrophage and adipocyte IGF1 maintain adipose tissue homeostasis during metabolic stresses. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(1):172–83.

Spadaro O, et al. IGF1 Shapes Macrophage Activation in Response to Immunometabolic Challenge. Cell Rep. 19(2):225–34.

Richert MM, Wood TL. The insulin-like growth factors (IGF) and IGF type I receptor during postnatal growth of the murine mammary gland: sites of messenger ribonucleic acid expression and potential functions. Endocrinology. 1999;140(1):454–61.

Jones RA, Campbell CI, Gunther EJ, Chodosh LA, Petrik JJ, Khokha R, et al. Transgenic overexpression of IGF-IR disrupts mammary ductal morphogenesis and induces tumor formation. Oncogene. 2007;26(11):1636–44.

Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Wang Y, Collins LC, Hu R, Rosner B, et al. Expression of IGF1R in normal breast tissue and subsequent risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(1):243–50.

Gouon-Evans V, Rothenberg ME, Pollard JW. Postnatal mammary gland development requires macrophages and eosinophils. Development. 2000;127(11):2269–82.

Iyengar NM, Brown KA, Zhou XK, Gucalp A, Subbaramaiah K, Giri DD, et al. Metabolic obesity, adipose inflammation and elevated breast aromatase in women with normal body mass index. Cancer Prev Res. 2017;10(4):235–43.

Iyengar NM, Morris PG, Zhou XK, Gucalp A, Giri D, Harbus MD, et al. Menopause is a determinant of breast adipose inflammation. Cancer Prev Res. 2015;8(5):349–58.

Monk JM, Liddle DM, de Boer AA, Brown MJ, Power KA, Ma DWL, et al. Fish-oil–derived n–3 PUFAs reduce inflammatory and chemotactic Adipokine-mediated cross-talk between co-cultured murine splenic CD8+ T cells and adipocytes. J Nutr. 2015;145(4):829–38.

Sun X, Glynn DJ, Hodson LJ, Huo C, Britt K, Thompson EW, et al. CCL2-driven inflammation increases mammary gland stromal density and cancer susceptibility in a transgenic mouse model. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2017;19:4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Support

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center’s NIH Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA036727) for this project. Also, funding from the UNMC College of Medicine (LWK) Endowed Chair.

Additional information

Highlights

• Dietary long-chain omega-3 fatty acids (Lc-ω-3FAs) modulate mammary ductal end-point density and branching density in adult mice compared to mice receiving a high ω-6 FA containing diet.

• Dietary Lc-ω-3FAs downregulate the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, adipokines and growth factors and their receptors in association with decreased epithelial cell proliferation as compared to mice maintained on a high omega-6 (ω −6) FA containing diet

• Dietary Lc-ω-3FAs regulate the mammary fat pad (MFP) FA profile and is associated with adipocyte hypertrophy

• Dietary Lc-ω-3FAs decrease MG and abdominal adipose tissue inflammation relative to mice receiving a high ω-6 FA containing diet.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khadge, S., Thiele, G.M., Sharp, J.G. et al. Long-Chain Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Modulate Mammary Gland Composition and Inflammation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 23, 43–58 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-018-9391-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-018-9391-5