Abstract

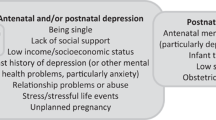

Prior investigations have examined risk factors associated to postpartum depression in immigrant women, but depression during pregnancy has received less attention. This study describes the prevalence and early determinants of antenatal depression among recent (≤ 5 years) and long-term immigrants (> 5 years), compared to Canadian-born women. 503 women completed standardized self-report questionnaires measuring sociodemographics and psychosocial factors. Multivariate logistic regressions identified first trimester risk factors for depression in each immigrant group. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was highest for recent immigrant (25.3–30.8%) compared to long-term immigrant (16.9–19.2%) and Canadian-born women (11.7–13.8%). Among recent immigrants, multiparity, higher stress and pregnancy-specific anxiety in early pregnancy increased the risk of antenatal depression. Among long-term immigrants, stress in the first trimester was significantly associated with antenatal depressive symptoms. Knowledge of modifiable risk factors (pregnancy-specific anxiety and stress) may help improve antenatal screening and inform the development of tailored interventions to meet the mental health needs of immigrant women during the perinatal period.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tobin CL, Di Napoli P, Beck CT. Refugee and immigrant women’s experience of postpartum depression: a meta-synthesis. J Transcult Nurs. 2018;29(1):84–100.

Jayaweera H, Quigley MA. Health status, health behaviour and healthcare use among migrants in the UK: evidence from mothers in the Millennium Cohort Study. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(5):1002–10.

Anderson FM, Hatch SL, Comacchio C, Howard LM. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(3):449–62.

Higginbottom GM, Hadziabdic E, Yohani S, Paton P. Immigrant women’s experience of maternity services in Canada: a meta-ethnography. Midwifery. 2014;30(5):544–59.

Higginbottom GM, Morgan M, Alexandre M, Chiu Y, Forgeron J, Kocay D, et al. Immigrant women’s experiences of maternity-care services in Canada: a systematic review using a narrative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2015;4:13.

Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Vigod S, Dennis C-L. Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:67–82.

Dennis CL, Merry L, Stewart D, Gagnon AJ. Prevalence, continuation, and identification of postpartum depressive symptomatology among refugee, asylum-seeking, non-refugee immigrant, and Canadian-born women: results from a prospective cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(6):959–67.

Dennis CL, Merry L, Gagnon AJ. Postpartum depression risk factors among recent refugee, asylum-seeking, non-refugee immigrant, and Canadian-born women: results from a prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(4):411–22.

Mechakra-Tahiri S, Zunzunegui MV, Seguin L. Self-rated health and postnatal depressive symptoms among immigrant mothers in Québec. Women Health. 2007;45(4):1–17.

Stewart DE, Gagnon A, Saucier JF, Wahoush O, Dougherty G. Postpartum depression symptoms in newcomers. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(2):121–4.

Sword W, Watt S, Krueger P. Postpartum health, service needs, and access to care experiences of immigrant and Canadian-born women. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(6):717–27.

Zelkowitz P, Saucier JF, Wang T, Katofsky L, Valenzuela M, Westreich R. Stability and change in depressive symptoms from pregnancy to two months postpartum in childbearing immigrant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(1):1–11.

Ganann R, Sword W, Thabane L, Newbold B, Black M. Predictors of postpartum depression among immigrant women in the year after childbirth. J Womens HEALTH. 2016;25(2):155–65.

Alhasanat D, Fry-McComish J. Postpartum depression among immigrant and Arabic women: literature review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(6):1882–94.

World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund. Mental health aspects of women's reproductive health: a global review of the literature. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–83.

Underwood L, Waldie K, D’Souza S, Peterson ER, Morton S. A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(5):711–20.

Underwood L, Waldie KE, D’Souza S, Peterson ER, Morton SM. A Longitudinal Study of Pre-pregnancy and Pregnancy Risk Factors Associated with Antenatal and Postnatal Symptoms of Depression: Evidence from Growing Up in New Zealand. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(4):915–31.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95.

Verreault N, Da Costa D, Marchand A, Ireland K, Dritsa M, Khalifé S. Rates and risk factors associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and with postpartum onset. Journal of psychosomomatic obstetrics & gynaecology. 2014;35(3):84–91.

Diaz MA, Le HN, Cooper BA, Muñoz RF. Interpersonal factors and perinatal depressive symptomatology in a low-income Latina sample. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007;13(4):328–36.

Miszkurka M, Goulet L, Zunzunegui MV. Contributions of immigration to depressive symptoms among pregnant women in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(5):358–64.

Shin H, Shin Y. Life Stress, Social Support, and Antepartum Depression among Married Immigrant Women from Southeast Asia. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2015;26:108.

Small R, Lumley J, Yelland J. Cross-cultural experiences of maternal depression: associations and contributing factors for Vietnamese, Turkish and Filipino immigrant women in Victoria. Australia Ethnicity & health. 2003;8(3):189–206.

Truijens SEM, Spek V, van Son MJM, Guid Oei S, Pop VJM. Different patterns of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(4):539–46.

Zelkowitz P, Schinazi J, Katofsky L, Saucier JF, Valenzuela M, Westreich R, et al. Factors associated with depression in pregnant immigrant women. Transcult Psychiatry. 2004;41(4):445–64.

Rwakarema M, Premji SS, Nyanza EC, Riziki P, Palacios-Derflingher L. Antenatal depression is associated with pregnancy-related anxiety, partner relations, and wealth in women in Northern Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens health. 2015;15:68.

Bekele D, Worku A, Wondimagegn D. Prevalence and associated factors of mental distress during pregnancy among antenatal care attendees at Saint Paul’s Hospital. Addis Ababa Obstetr Gynecol Int J. 2017;7:00269.

Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, Barry KL. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health. 2003;12(4):373–80.

Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(1):5–14.

Rubertsson C, WaldenstrÖm U, Wickberg B, Rådestad I, Hildingsson I. Depressive mood in early pregnancy and postpartum: prevalence and women at risk in a national Swedish sample. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2005;23(2):155–66.

Rubertsson C, Wickberg B, Gustavsson P, Rådestad I. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):97–104.

Augusto ALP, de Abreu Rodrigues AV, Domingos TB, Salles-Costa R. Household food insecurity associated with gestacional and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–11.

Richards M, Weigel M, Li M, Rosenberg M, Ludema C. Household food insecurity and antepartum depression in the National Children’s Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;44:38–44.

Waldie KE, Peterson ER, D’Souza S, Underwood L, Pryor JE, Carr PA, et al. Depression symptoms during pregnancy: evidence from growing up in New Zealand. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:66–73.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8(2):99–107.

Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:288–90.

O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388–406.

Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350–64.

Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Dada AO, Fasoto OO. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for depression in late pregnancy among Nigerian women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(4):267–72.

Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Ove SS. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(4):243–9.

Carpiniello B, Pariante C, Serri F, Costa G, Carta M. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in Italy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1997;18(4):280–5.

Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM, Mann R, Brealey S. Instruments to identify post-natal depression: which methods have been the most extensively validated, in what setting and in which language? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14(1):72–6.

Yali AM, Lobel M. Coping and distress in pregnancy: an investigation of medically high risk women. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 1999;20(1):39–52.

Lobel M, Cannella DL, Graham JE, DeVincent C, Schneider J, Meyer BA. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):604–15.

Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Perra O, Alderdice F, Lynn F, Lobel M, García-García I, et al. Psychometric validation of the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ) in pregnant women in Spain. Women Health. 2019;59(8):937–52.

Penengo C, Colli C, Garzitto M, Driul L, Cesco M, Balestrieri M. Validation of the Italian version of the Revised Prenatal Coping Inventory (NuPCI) and its correlations with pregnancy-specific stress. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–14.

Yuksel F, Akin S, Durna Z. The Turkish adaptation of the" Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire": a reliability/validity and factor analysis study/" Prenatal Distres Olcegi" nin Turkce’ye uyarlanmasi ve faktor analizi. J Educ Res Nursing. 2011;8(3):43–52.

Esfandiari M, Faramarzi M, Gholinia H, Omidvar S, Nasiri-Amiri F, Abdollahi S. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Persian version of revised prenatal distress questionnaire in second and third trimesters. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2020;25(5):431.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Cohen S, Williamson G, editors. Psychological stress in a probability sample of the United States. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988.

Eskildsen A, Dalgaard VL, Nielsen KJ, Andersen JH, Zachariae R, Olsen LR, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Danish consensus version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2015;41:486–90.

Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, Varvogli L, Gnardellis C, Chrousos GP, et al. Perceived stress scale: reliability and validity study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(8):3287–98.

Baik SH, Fox RS, Mills SD, Roesch SC, Sadler GR, Klonoff EA, et al. Reliability and validity of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 in Hispanic Americans with English or Spanish language preference. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(5):628–39.

Lee J, Shin C, Ko Y-H, Lim J, Joe S-H, Kim S, et al. The reliability and validity studies of the Korean version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Korean J Psychosomat Med. 2012;20(2):127–34.

Huang F, Wang H, Wang Z, Zhang J, Du W, Su C, et al. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in a community sample of Chinese. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–7.

Lesage F-X, Berjot S, Deschamps F. Psychometric properties of the French versions of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25(2):178–84.

Mimura C, Griffiths P. A Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale: cross-cultural translation and equivalence assessment. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):1–7.

Nordin M, Nordin S. Psychometric evaluation and normative data of the Swedish version of the 10-item perceived stress scale. Scand J Psychol. 2013;54(6):502–7.

Chaaya M, Osman H, Naassan G, Mahfoud Z. Validation of the Arabic version of the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) among pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):1–7.

Jovanović V, Gavrilov-Jerković V. More than a (negative) feeling: validity of the Perceived Stress Scale in Serbian clinical and non-clinical samples. Psihologija. 2015;48(1):5–18.

Klein EM, Brähler E, Dreier M, Reinecke L, Müller KW, Schmutzer G, et al. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale–psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–10.

Dao-Tran T-H, Anderson D, Seib C. The Vietnamese version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): translation equivalence and psychometric properties among older women. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–7.

Siqueira RR, Ferreira HAA, Romélio RAC. Perceived stress scale: reliability and validity study in Brazil. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(1):107–14.

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T. The Thai version of the PSS-10: an investigation of its psychometric properties. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2010;4(1):1–6.

Remor E. Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Span J Psychol. 2006;9(1):86.

Örücü MÇ, Demir A. Psychometric evaluation of perceived stress scale for Turkish university students. Stress Health. 2009;25(1):103–9.

Milgrom J, Hirshler Y, Reece J, Holt C, Gemmill AW. Social support—a protective factor for depressed perinatal women? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1426.

Saad M. Examining the social patterning of postpartum depression by immigration status in Canada: an exploratory review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(2):312–8.

Goyal D, Gay C, Lee KA. How much does low socioeconomic status increase the risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms in first-time mothers? Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(2):96–104.

Nakamura A, Lesueur FE-K, Sutter-Dallay A-L, Franck J-È, Thierry X, Melchior M, et al. The role of prenatal social support in social inequalities with regard to maternal postpartum depression according to migrant status. J Affect Disorders. 2020;272:465–73.

Quintanilha M, Mayan MJ, Thompson J, Bell RC. Contrasting “back home” and “here”: how Northeast African migrant women perceive and experience health during pregnancy and postpartum in Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1–8.

Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Migration, social support and perinatal health: an origin-destination analysis of Puerto Rican women. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(2):166–83.

Martinez-Schallmoser L, MacMullen NJ, Telleen S. Social support in Mexican American childbearing women. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(6):755–60.

Martinez-Schallmoser L, Telleen S, MacMullen NJ. The effect of social support and acculturation on postpartum depression in Mexican American women. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(4):329–38.

Coburn SS, Gonzales NA, Luecken LJ, Crnic KA. Multiple domains of stress predict postpartum depressive symptoms in low-income Mexican American women: the moderating effect of social support. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(6):1009–18.

Glazier RH, Elgar FJ, Goel V, Holzapfel S. Stress, social support, and emotional distress in a community sample of pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynecol. 2004;25(3–4):247–55.

Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey. 2014.

Maria-da-Conceição FS, Figueiredo MH. Immigrant women’s perspective on prenatal and postpartum care: systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(1):276–84.

Statistics Canada. Census in Brief: Linguistic integration of immigrants and official language populations in Canada. 2017.

Chen HH, Hwang FM, Wang KL, Chen CJ, Lai JCY, Chien LY. A structural model of the influence of immigrant mothers’ depressive symptoms and home environment on their children’s early developmental outcomes in Taiwan. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(6):603–11.

Zelkowitz P, Tamara HM. Screening for post-partum depression in a community sample. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40(2):80–6.

Cheng C-Y, Fowles ER, Walker LO. Postpartum maternal health care in the United States: a critical review. J Perinat Educ. 2006;15(3):34.

Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H. Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(5):683–714.

Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2015;28(3):179–93.

Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70(5):490–8.

Freeman MP. Perinatal depression: recommendations for prevention and the challenges of implementation. JAMA. 2019;321(6):550–2.

Spinelli MG, Endicott J. Controlled clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus parenting education program for depressed pregnant women. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):555–62.

Muñoz RF, Le H-N, Ippen CG, Diaz MA, Urizar GG Jr, Soto J, et al. Prevention of postpartum depression in low-income women: Development of the Mamás y Bebés/Mothers and Babies Course. Cogn Behav Pract. 2007;14(1):70–83.

Le H-N, Perry DF, Stuart EA. Randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention for perinatal depression in high-risk Latinas. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):135.

Kieffer EC, Caldwell CH, Welmerink DB, Welch KB, Sinco BR, Guzmán JR. Effect of the healthy MOMs lifestyle intervention on reducing depressive symptoms among pregnant Latinas. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(1):76–89.

Kirmayer LJ, Weinfeld M, Burgos G, du Fort GG, Lasry J-C, Young A. Use of health care services for psychological distress by immigrants in an urban multicultural milieu. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(5):295–304.

Whitley R, Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D. Understanding immigrants’ reluctance to use mental health services: a qualitative study from Montreal. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(4):205–9.

Tiwari SK, Wang J. Ethnic differences in mental health service use among White, Chinese, South Asian and South East Asian populations living in Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(11):866.

Merry LA, Gagnon AJ, Kalim N, Bouris SS. Refugee claimant women and barriers to health and social services post-birth. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(4):286–90.

Ahmed A, Bowen A, Feng CX. Maternal depression in Syrian refugee women recently moved to Canada: a preliminary study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–11.

Nwoke CN, Okpalauwaekwe U, Bwala H. Mental health professional consultations and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders among immigrants: multilevel analysis of the Canadian community health survey. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7(9):e19168.

Matvienko-Sikar K, Flannery C, Redsell S, Hayes C, Kearney PM, Huizink A. Effects of interventions for women and their partners to reduce or prevent stress and anxiety: a systematic review. Women and Birth. 2020;34(2): e97–e117.

Giacco D, Matanov A, Priebe S. Providing mental healthcare to immigrants: current challenges and new strategies. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):282–8.

Guruge S, Thomson MS, George U, Chaze F. Social support, social conflict, and immigrant women’s mental health in a Canadian context: a scoping review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(9):655–67.

Thomson MS, Chaze F, George U, Guruge S. Improving immigrant populations’ access to mental health services in Canada: a review of barriers and recommendations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(6):1895–905.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant awarded to Dr Deborah Da Costa by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; #299916).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was granted by McGill Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the ethics review boards of the participating hospitals. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vaillancourt, M., Lane, V., Ditto, B. et al. Parity and Psychosocial Risk Factors Increase the Risk of Depression During Pregnancy Among Recent Immigrant Women in Canada. J Immigrant Minority Health 24, 570–579 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01284-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01284-7