Abstract

States vary in their participation in federal immigration enforcement, leading to differing state-level policy contexts that profoundly shape the lives of immigrants. This paper examines the effects of sanctuary policies and driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants on immigrants’ children’s access to preventative healthcare. The 2008–2016 Medical Panel Expenditure Survey merged with state-level policy data were analyzed using a difference-in-difference OLS regression. Outcome variables included whether the child had a usual source of care, any unmet medical needs, or a well child check-up. State driver’s license and sanctuary policies were associated with having a usual source of care and fewer unmet medical needs among children of immigrants. The recent pandemic highlights the importance of access to preventative health care. State policies that limit federal immigration enforcement involvement are associated with improved access to preventative health services among immigrants’ children, most of whom are U.S. citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent studies have documented negative health outcomes for immigrants and their families when state/local law enforcement more actively participate in federal immigration enforcement. However, few studies to date have examined the health impacts of “immigrant-friendly” policies. States and localities have adopted two types of “immigrant-friendly” policies that may protect undocumented immigrants from federal immigration enforcement: (1) allowing undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses and (2) limiting state/local law enforcement’s involvement in federal immigration enforcement efforts, colloquially known as sanctuary policies. We examine the impacts of these policies on children of immigrants’ access to preventative healthcare, measured by whether the children (1) had a usual source of care (USC) provider, (2) had unmet medical needs, or (3) had recent well-child visits. We use difference-in-difference regressions to analyze data from the medical expenditure panel survey (MEPS) merged with state-level policies.

Our analysis shows that sanctuary policies and driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants are associated with better access, on some measures, among children of immigrants. Both policies were associated with a reduced likelihood of unmet medical needs for children with non-citizen, immigrant parents. In addition, policies allowing undocumented immigrants to get driver’s licenses were associated with an increased likelihood of having a USC among immigrant children living with non-citizen parents. These results are important given the wide variation in state responses to federal immigration enforcement and the importance of access to health care in addressing a pandemic like COVID-19.

Background

About a quarter of U.S. children have immigrant parents [1]. An estimated 5.6 million children in the United States, or about 7%, live with an undocumented immigrant parent who lacks permission to live or work in the United States [2]. Of these children, over 75% live in “mixed-status” families in which some members are undocumented immigrants and others are U.S.-born or legally residing [2]. In this paper, we use the shorthand immigrant to refer to all individuals, both legally residing and undocumented, who are not U.S.-born and are not naturalized U.S. citizens.

States have taken a range of approaches toward the treatment of undocumented immigrants by local law enforcement agencies and toward the expansion of public benefits for both legally-residing and undocumented immigrants. These state policy choices create different contexts for immigrants and their children, which may impact their health.

Driver’s License Policies

Undocumented immigrants could legally obtain a driver’s license in all states until 1993, when California restricted driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants. By 2011, only three states (Utah, New Mexico, and Washington) allowed driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants. As of June 2020, 15 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia allow driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants.

Sanctuary Policies

The federal immigration enforcement program “Secure Communities” was launched as a pilot in 2008 and expanded nationally thereafter. Under Secure Communities, state and local law enforcement agencies submit fingerprints of arrestees for checks against Department of Homeland Security (DHS) databases. If an immigration violation is found, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials may issue a detainer request to local law enforcement to hold that person for up to 48 h after they would have otherwise been released from jail, so that ICE can take custody. Starting in 2011, some states, cities, and counties passed policies to limit cooperation with the Secure Communities’ detainer requests. Such policies are often colloquially referred to as “sanctuary policies.”

Secure Communities led to the deportation of many immigrants who had not committed serious criminal offenses [3], thus un late 2014, it was replaced with the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) [4], which focused on detaining and deporting immigrants who were national security threats, had been convicted of serious crimes, or were new arrivals to the U.S. In 2017, President Trump issued an executive order that ended PEP and reinstated the Secure Communities program.

Public Health Insurance Policies for Non-citizen Immigrants

Children of immigrants have low health insurance rates, even when they are U.S. citizens, especially when they have undocumented immigrant parents [5,6,7,8]. After controlling for income, families with immigrant parents have lower rates of take-up of public benefits, such as Medicaid, than families headed by citizens, due in large part to immigrants’ restricted eligibility for these programs [9]. In 1996, most lawful permanent residents (LPRs) were excluded from accessing Medicaid, during their first five years with LPR status. Undocumented immigrants have always been ineligible for federally funded Medicaid. However, States may elect to use state funds to allow otherwise excluded immigrants to use Medicaid [10, 11].

Conceptual Model

Effects of State Immigrant-Related Policies on Immigrants’ Health

Emerging evidence shows that having undocumented immigrant parents affects children’s well-being and health, likely due to the lack of resources and the ever-present anxiety about the future that undocumented immigrants face. For example, having undocumented parents has been tied to greater anxiety and depression in children [12, 13] and increased ICE activities, such as raids, detention, and deportation has been linked to a deterioration in immigrant patients’ physical and psychological health [14]. In states and localities that increase participation in federal immigration enforcement, Latino immigrants show worsening mental health distress [15].

Research shows that lack of transportation resulting from state restrictions on driver’s licenses creates a significant barrier to obtaining health care [16]. In places with stricter immigration enforcement, a traffic stop for undocumented immigrants may be the first step toward detention and deportation [17, 18], leading to limited mobility. In surveys, undocumented immigrants have expressed high levels of fear of accessing public benefits, including medical services, due to fears of deportation [19, 20]. Stricter enforcement has been shown to reduce enrollment in public benefits, regardless of a child’s eligibility, for both children of undocumented immigrants and children of legal immigrants [21], and higher immigration enforcement deters Medicaid enrollment among U.S.-citizen children of immigrant mothers [22, 23]. All these associations, however, may vary across the United States because state and local governments have varied in their responses to increasing federal immigration enforcement, creating different immigration policy contexts state by state and locality by locality.

Methods

Data

Information on children, parent and household characteristics come from the MEPS. MEPS is a nationally representative, overlapping panel survey of approximately 30,000 respondents annually. A new panel is drawn every year and respondents are interviewed five times over two years. We use the full-year cross sectional data files from MEPS, each of which consists of two panels. Interviews are conducted in English or Spanish, with interpretation available for speakers of other languages. The first interview rounds have response rates ranging from 72 to 75%, and response rates for subsequent rounds are all above 95%. We include 2008–2016 MEPS data to capture events before and after some states changed driver’s license policies and implemented sanctuary policies. Information on the adoption of policies in states come from the State Policy Database, publicly available at: https://www.urban.org/features/state-immigration-policy-resource [24]. We merged the MEPS data with this data source by state. Our sample consists of 66,314 children.

This research was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University, the university where the lead author was employed at the time the analysis was conducted.

Measures

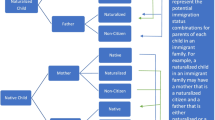

Children were categorized into four mutually exclusive groups based on their own immigration status and that of their parent(s): (1) U.S.-Born Child and Parents: children living in households where both the child and their parents are born in the U.S., which we used as the comparison group; (2) U.S.-Born Child and Immigrant Parent(s): children who were born in the U.S. and live in households in which at least one parent is an immigrant and is not a naturalized U.S. citizen; and (3) Child and Parents, Immigrants: children living in households in which both the child and at least one of their parents is an immigrant and no parent is a naturalized U.S. citizen; (4) Parent(s) Naturalized Citizen(s): children living in a household with at least one naturalized-citizen parent and neither parent is a non-naturalized immigrant. We do not expect the policies to affect families headed by naturalized citizens because they are not subject to deportation.

This study examines three outcome variables that measure access to healthcare. For each child, respondents reported whether the child had a usual source of care, a specific person or place to go if ill or in need of health advice; unmet medical need, whether “you or a doctor” thought the child needed care and, if so, whether they were unable to get it or were delayed in getting it; and whether the child had at least one well-child visit or checkup during the year.

We examine the extent to which driver’s license policies and sanctuary polices affect the child’s access to healthcare. For sanctuary policies, if some or all of the counties where at least half of immigrants in a state live had such a policy or the whole state had such a policy, the state was coded as having such a policy. We used this state-level approach because substate indicators of residence were not available to us in the MEPS data. This imprecise measure of sanctuary policies will likely result in underestimating the impact of sanctuary policies on children of non-citizen immigrants; the analysis should provide a lower bound of the impact of sanctuary policies. The policy variables are lagged by a single year for 2007–2015, as prior research indicates lagged effect of sanctuary policies on deportations [25]

We include variables capturing child, parent, household and county characteristics as control variables in our analysis. These include age of oldest parent, age of child, gender of child, health insurance status of child, family income as percentage of the federal poverty line, the highest degree obtained by either parent, interview language (English, Spanish, other), number of children in the household, the parents’ rating of the child’s health status, and whether the family lived in an urban, suburban, or rural area. In addition to these variables, we use state-fixed effects to control for differences across states that did not change during the period of the analysis.

We also controlled for county and state-level characteristics that may be correlated with state adoption of immigration enforcement policies and that might affect immigrant households’ access to healthcare. At the county-level, we control for number of doctors per 1000 residents. At the state-level, we control for percent Latino, whether the state provides public health insurance to legal immigrants prior to the 5-year ban, whether the state provides public health insurance to undocumented immigrant children, whether the state provides TANF cash assistance to legal permanent residents who have not satisfied the 5-year ban on receiving federal assistance, whether the state provides food assistance to legal permanent residents who have not satisfied the 5-year ban on receiving federal assistance and whether the largest immigrant counties in the state have 287(g) agreements with ICE (counties that want to use more local law enforcement resources to participate more vigorously in federal immigration enforcement can enter into 287(g) agreements that allow them to do so).

Table 1 shows weighted estimates of the characteristics of families in our sample by immigration status.

Analysis

We use a difference-in-difference regression model of the following form:

where Y is a measure of the dependent variable (USC, unmet need, well-child visit) for child i in state s at time t + 1, DRLCst is an indicator for whether the state has a policy of allowing driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants or has a sanctuary policy at time t, IMMIGRANTist is a set of three dichotomous variables indicating which of the four household types child i lives in at time t (the omitted category is U.S.-born children living with U.S.-born parents), DRLCst*IMMIGRANTist is a set of interaction terms, and Xist is a vector of the control variables previously described. State and time fixed effects are ηs and υt, respectively, and the error term is εist. The model is estimated separately for drivers’ license policies and sanctuary policies using OLS regressions, with all estimates weighted to make them nationally representative and standard errors adjusted using linearization.

The parameter of interest is β1, which captures the effect of living in states that have implemented particular policies, controlling for all the covariates in the model. For example, using USC as the outcome and driver’s licenses as the policy, a positive coefficient estimate for β1 would indicate that children in a particular family-level immigration situation (given by IMMIGRANTist) who live in a state that implemented a policy allowing undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses are more likely to have a USC than children living in states that did not. Note that this interpretation relies on the fact that χ, the coefficient estimate for the “main” effect of the policy change, captures the effects of all time-varying characteristics, both observed and unobserved, that affect the likelihood of having a USC for all children (not just children with immigrant parents). We estimate separate models to assess the impact of drivers’ license policies and sanctuary policies.

The MEPS data, like most surveys, does not ask respondents whether they are legally residing in the United States. About 42% of non-U.S. citizen immigrants are undocumented. We anticipate that the driver’s license and sanctuary policies would have a stronger impact on the outcomes of children with undocumented immigrant parents. We use sensitivity analyses, described at the end of the paper, to examine this issue in more depth. Additionally, because of the imprecision of our measurement of legal status, it is likely that are models are lower bound estimates of the impact of these policies.

Results

The analyses suggest that, at least for some outcomes and some children, driver’s license policies and sanctuary policies improve access to health care. The estimates in Table 2 show that, among immigrant children with immigrant parents, living in a state that allows undocumented immigrants to obtain drivers’ licenses is associated with an increase in the probability of having a USC of 10.69 percentage points and a decrease in having unmet medical need of 1.98 percentage points (Table 2). Given that only 2% of children have unmet medical need, the effect of drivers’ license policies on this outcome is large.

We also find that living in a state with sanctuary policies is associated with the probability of having a USC and unmet need. Among immigrant children with non-citizen immigrant parents, living in states with sanctuary policies is associated with a 6.62 percentage point increase in the likelihood of having a USC (Table 3). Among native-born children living with non-citizen immigrant parents, living in a state with sanctuary policies is associated with a 1.1 percentage point decrease in the likelihood of having unmet medical needs. This finding suggests that a parent’s immigrant status can affect a child’s access to health care even when that child has all the entitlements of citizenship.

We did not find any statistically significant effects of drivers’ license policies or sanctuary policies on the likelihood of having a well-child visit or a checkup. One possible explanation for this is that we have not adequately controlled for the age of children in our models. Recommendations for well-child visits differ by age; Table 1 shows that the average age of children differs across the different family types. Our model may not capture the functional form of the relationship between the age of children and the likelihood of well-child/checkups. We did try other functional forms (i.e. categorical variables based on various age cutoffs) and the resulting estimates were never significant.

The MEPS data, like most surveys, does not include information about non-citizen immigrants’ legal status, thus we were unable to identify parents who are undocumented immigrants. Driver’s license and sanctuary policies are potentially most beneficial for undocumented immigrants, and it is likely that the effects of these policies will be larger for children of undocumented immigrants. To explore this, we regrouped immigrant parents based on whether they could be undocumented. Using a modified version of Borjas’ approach (2017), we categorize immigrants as “legally-residing” if they have certain characteristics associated with legal status, including receipt of government benefits restricted to legally-residing immigrants, arrival in the U.S. prior to 1980, or Cuba as country of origin. Immigrants who could not be identified as “legally residing” we categorized as “possibly undocumented.” This modified method of imputing legal status is imprecise because many legally residing immigrants may not have the characteristics we used as the criterion for “legally residing” (e.g. most legal immigrants do not receive public assistance, etc.). Regardless, results from this analysis suggest that the effects of drivers’ license policies and sanctuary policies on access are driven mostly by children of “possibly undocumented” parents (analyses available upon request).

Discussion

This study examines the effects of immigrant-friendly policies on children’s health outcomes. It supports prior qualitative work that suggests that lack of access to driver’s licenses prevents undocumented immigrant parents from obtaining important services for themselves and their children [16]. And it parallels a prior quantitative study showing that inclusive policies led to higher levels of health insurance coverage among non-citizen immigrants [26]. The effects of driver’s license policies and sanctuary policies on usual source of care are similar across immigrant family types; however, different patterns of significance emerge for the model of unmet medical needs. We do not find a significant impact of driver’s licenses on unmet medical needs, while we find that sanctuary policies significantly reduce unmet medical needs for mixed status families. Unmet need is a relatively rare event for children, regardless of their or their parents’ immigration status. The sizes of the effects are similar across the two models, and the difference in statistical significance may reflect variation in the size of the standard errors. Alternatively, it may be that sanctuary policies predict protective health outcomes for mixed-status families because these policies more widely benefit immigrant families. In other words, the risk of parental deportation negatively affects mixed status families, as well as families composed of noncitizens.

This study also extends the quantitative studies analyzing a range of national databases that show detrimental effects of states’ increased participation in federal immigration enforcement on immigrant families’ and children’s well-being. These studies have demonstrated that children of non-citizen immigrants in states that participate more in federal immigration enforcement experience more material hardship [27], have worse educational outcomes [28], and are less likely to enroll in public benefits for which they are eligible [21, 22]. There are, however, some limitations to this study.

Study Limitations

Selective Out-migration

Some evidence suggests that immigration enforcement pushes undocumented immigrants to friendlier states [29,30,31], but has not established whether these movers differ from immigrants who remain in high-enforcement states. It is possible that selective out-migration leads to immigrant families with more resources to move from states without these policies to states that have them. This could lead to a correlation of these policies with more access to preventive health care.

Analysis of Local Policy Variations

Sanctuary policies are primarily dictated by local governments and police forces. Local policy variations can be especially important when political environments at the local level—where limited cooperation agreements can be implemented—are more conducive to supporting undocumented immigrant families than are policies at the state level. Prior work has documented county-level variation in how often county jails cooperate with ICE to deport noncitizens [32]. Future sub-state analyses should account for variation in local demographics and other factors related to enforcement, such as unemployment or political voting patterns. Our analysis aggregates these policies into a state indicator, but further examination of county level differences may be warranted.

Contribution to Literature

The implications of this study expand beyond just health policy to the implications of immigration policy for not only immigrant families, but also for all Americans. As the recent COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated, strong public health requires access to health services for all people. Ensuring that children of immigrants can access basic preventive healthcare will be important for the ongoing health of our nation, and states that adopt immigrant-friendly policies may be better able to ensure their healthcare access. Additionally, the effects of driver’s licenses on children’s health outcomes demonstrates the importance of adequate transportation to improve access to health care, as well as other services children need.

References

Urban Institute. Children of immigrants data tool. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2019.

Passel J, Cohn D. U.S. unauthorized immigrant total dips to lowest level in a decade. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2018.

East C. Secure Communities: Broad impacts of increased immigration enforcement. Boston: EconoFacts; 2020.

Chishti M, Hipsman F. Sanctuary cities come under scrutiny, as does federal-local immigration relationship. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2015.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Health coverage of immigrants. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020.

Weathers AC, Novak SP, Sastry N, Norton EC. Parental nativity affects children’s health and access to care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(2):155–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-007-9061-y.

Acevedo-Garcia D, Stone LC. State variation in health insurance coverage for US citizen children of immigrants. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):434–46. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.434.

Ziol-Guest KM, Kalil A. Health and medical care among the children of immigrants. Child Dev. 2012;83(5):1494–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01795.x.

Ku L, Bruen B. Poor immigrants use public benefits at a lower rate than poor native-born Citizens. Washington, DC: Cato Institute; 2013.

Fix ME, editor. Immigrants and welfare: The impact of welfare reform on America’s newcomers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009.

Kretsedemas P, Aparicio A, editors. Immigrants, welfare reform, and the poverty of policy. Westport: Praeger; 2004.

Dreby J. The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74(4):829–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00989.x.

Potochnick SR, Perreira KM. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: key correlates and implications for future research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(7):470–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4ce24.

Hacker K, Chu J, Arsenault L, Marlin RP. Provider’s perspectives on the impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activity on immigrant health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):651–65.

Wang J, Kaushal N. Health and mental health effects of local immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: National Bureau of Economics; 2018.

Koball H, Capps R, Hooker S, Perreira K, Campetella A, Pedroza JM, Monson W, Huerta S. Health and social service needs of US-citizen children with detained or deported parents. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2015.

Waslin ML. Driving while immigrant: driver’s license policy and immigration enforcement. In: Brotherton D, Stageman D, Leyro S, editors. Outside justice. New York: Springer; 2013.

Capps R, Rosenblum MR, Chishti M, Rodriguez C. Delegation and divergence: 287(g) state and local immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2011.

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Puttitanun T, Martinez-Donate A. How do tougher immigration measures affect unauthorized immigrants? Demography. 2013;50(3):1067–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0200-x.

Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. J Immigr Health. 2001;3(3):151–6. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011389105821.

Vargas ED, Pirog MA. Mixed-status families and WIC uptake: the effects of risk of deportation on program use. Soc Sci Q. 2016;97(3):555–72.

Watson T. Inside the refrigerator: immigration enforcement and chilling effects in Medicaid participation. Working Paper 16278. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2010. http://www.nber.org/papers/w16278. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Watson T. Enforcement and immigrant location choice.” Working Paper 19626. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2013. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19626. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Gelatt J, Koball H, Bernstein H, Runes C, Pratt E. State immigration enforcement policies: How they impact low-income households. 2017. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/90091/state-immigration-enforcement-policies.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Hausman D. Sanctuary policies reduce deportations without increasing crime. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(44):27262.

De Trinidad Young M, Leon-Perez G, Wells C, Wallace S. Inclusive state immigrant policies and health insurance among Latino, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Black and White noncitizens in the United States. Ethn Health. 2017;24(8):960–72.

Gelatt J, Koball H, Bernstein H. State immigration enforcement policies and material hardship for immigrant families. Child Welfare. 2018;26(5):100–12.

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Lopez M. Falling through the cracks? Grade retention and school dropout among children of likely unauthorized immigrants. Am Econ Rev. 2015;105(5):598–603.

Leerkes A, Leach M, Bachmeier J. Borders behind the border: an exploration of state-level differences in migration control and their effects on US migration patterns. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2012;38(1):111–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.640023.

Lofstrom M, Bohn S, Raphael S. Lessons from the 2007 legal Arizona workers act. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California; 2011.

Watson T. “Enforcement and immigrant location choice.” Working Paper 19626. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2013. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19626. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Pedroza J. Deportation discretion: tiered influence, minority threat, and “Secure Communities” deportations.”. Policy Stud J. 2019;47(3):624–46.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported through a grant by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), Evidence for Action Program. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors alone and should not be construed as representing the opinions of RWJF. The views in this article are those of the authors and no official endorsement from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koball, H., Kirby, J. & Hartig, S. The Relationship Between States’ Immigrant-Related Policies and Access to Health Care Among Children of Immigrants. J Immigrant Minority Health 24, 834–841 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01282-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01282-9