Abstract

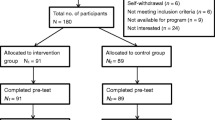

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) may offer a means for Latinx families to ameliorate stress, enhance emotion regulation, and foster social support. We assessed pilot data from Latinx parents in Eastside Los Angeles (n = 27) matched with their children aged 10–16 (n = 32) to determine whether participation in a community-derived MBI was associated with greater improvements in dispositional mindfulness, perceived stress, emotion regulation, and family social support compared to a control condition. Compared to the control group, parents in the MBI group showed greater reductions in perceived stress scale (PSS) scores (B = − 2.94, 95% CI [− 5.58, − 0.39], p = 0.029), while their children reported greater increases in perceived social support from family (B = 2.32, 95% CI [0.26, 4.38], p = 0.027). Findings show a community-derived MBI may improve stress in Latinx parents and social support for their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schwartz SJ, et al. Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among hispanic immigrant adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(4):433–9.

Cano MÁ, et al. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. J Adolesc. 2015;42:31–9.

Lorenzo-Blanco Elma I, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of family functioning among recent immigrant adolescents and parents: links with adolescent and parent cultural stress, emotional well-being, and behavioral health. Child Dev. 2017;90(2):506–23.

Smokowski Paul R, et al. Acculturation and latino family processes: how cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Fam Relat. 2008;57(3):295–308.

Alexis OM, et al. Latino families: the relevance of the connection among acculturation, family dynamics, and health for family counseling research and practice. Fam J. 2006;14(3):268–73.

Haine-Schlagel R, Walsh NE. A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(2):133–50.

Villatoro AP, et al. Family culture in mental health help-seeking and utilization in a nationally representative sample of Latinos in the United States: the NLAAS. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(4):353–63.

Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48.

Creswell JD. Mindfulness interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68(1):491–516.

Amaro H, Black DS. Moment-by-moment in women’s recovery: randomized controlled trial protocol to test the efficacy of a mindfulness-based intervention on treatment retention and relapse prevention among women in residential treatment for substance use disorder. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;62:146–52.

Edwards M, et al. Effects of a mindfulness group on latino adolescent students: examining levels of perceived stress, mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological symptoms. J Spec Group Work. 2014;39(2):145–63.

Fung J, et al. A pilot randomized trial evaluating a school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth. Mindfulness. 2016;7(4):819–28.

Coatsworth DJ, et al. Integrating mindfulness with parent training: effects of the mindfulness-enhanced strengthening families program. Dev Psychol. 2015;51(1):26–35.

Haydicky J, et al. Mechanisms of action in concurrent parent-child mindfulness training: a qualitative exploration. Mindfulness. 2017;8:1018.

Parent J, et al. Parent mindfulness and child outcome: the roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness. 2010;1(4):254–64.

Duncan LG, et al. A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12(3):255–70.

Gouveia MJ, et al. Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: the mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness. 2016;7:700–12.

May LM, et al. Parenting an early adolescent: a pilot study examining neural and relationship quality changes of a mindfulness intervention. Mindfulness. 2016;7(5):1203–13.

Escobedo P, et al. Community needs assessment among latino families in an urban public housing development. Hispan J Behav Sci. 2019;41(3):344–62.

Tobin J, et al. A community-based mindfulness intervention among latino adolescents and their parents: a qualitative feasibility and acceptability study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00985-9.

QuickFacts: East Los Angeles CDP, California. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/ (2016)

Brown KW, et al. Assessing adolescent mindfulness: validation of an adapted Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in adolescent normative and psychiatric populations. Psychol Assess. 2011;23(4):1023–33.

Soler J, et al. Psychometric proprieties of Spanish version of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2012;40(1):19–26.

Calvete E, et al. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale-Adolescents (MAAS-A). Behav Psychol Psicol Conduct. 2014;22(2):277–91.

Cohen S, et al. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Bjureberg J, et al. Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: the DERS-16. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38(2):284–96.

Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54.

Zimet GD, et al. The multidimensional Scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Zimet GD, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7.

Shahar E. Evaluating the effect of change on change: a different viewpoint. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(1):204–7.

Burwell SM. Annual update of the hhs poverty guidelines. In: Services DoHaH, editor. Fed Regist. Washington, DC: Office of the Federal Register; 2015. p. 3236–7.

Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin. 2017;40(4):739–49.

Lindsay EK, et al. Acceptance lowers stress reactivity: dismantling mindfulness training in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;87:63–73.

Black DS, et al. Sitting-meditation interventions among youth: a review of treatment efficacy. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e532–41.

Black DS, Fernando R. Mindfulness training and classroom behavior among lower-income and ethnic minority elementary school children. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23(7):1242–6.

Liehr P, Diaz N. A pilot study examining the effect of mindfulness on depression and anxiety for minority children. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;24(1):69–71.

Brown-Iannuzzi JL, et al. Discrimination hurts, but mindfulness may help: trait mindfulness moderates the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Pers Individ Dif. 2014;56:201–5.

Park T, et al. Mindfulness: a systematic review of instruments to measure an emergent patientreported outcome (PRO). Qual Life Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0395-8.

Chiesa A. The difficulty of defining mindfulness: current thought and critical issues. Mindfulness. 2013;4(3):255–68.

Chiesa A, et al. Psychological mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions: what do we know? Holist Nurs Pract. 2014;28(2):124–48.

Goodman MS, et al. Measuring mindfulness in youth: review of current assessments, challenges, and future directions. Mindfulness. 2017;8:1409.

Baer RA, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (#1R24MD007978), the University of California, Los Angeles Postdoctoral Fellowship Training Program in Global HIV Prevention Research NIMH grant 5T32MH080634-13, and National Institute of Mental Health (#P30MH058107). Thanks to the following staff and volunteers who made this project possible. From Bienestar: Frank Galvan, Carina Palacios, Flor Vindel, Ying-Tung Chen; From Legacy LA: Ruby Rivera, Sarah Reyes, Isaac Caldera, Jeanny Marroquin, Isabel Marquez, Martha Gonzalez, Marlene Arazo, Karina Licon, Evangeline Ordaz; From USC: Amy Rodriquez, Maryann Pentz, Tess Cruz, Jessica Tobin, Patricia Escobedo, James Thing, Jimi Huh, Donna Spruijt-Metz; and consultants: Michael Mata, Peter Hovmand, and Jill Kuhlberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M.J., Hardy, J., Calanche, L. et al. Initial Efficacy of a Community-Derived Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Latinx Parents and their Children. J Immigrant Minority Health 23, 993–1000 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01154-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01154-2