Abstract

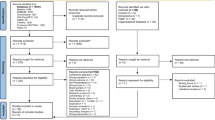

To explore the experiences of Latina immigrants with advanced breast cancer and their support networks. We conducted semi-structured interviews with low-income Latina immigrants with advanced breast cancer and their support networks (informal caregivers, physicians, and complementary medicine (CM) practitioners). Patient interviews explored patients’ illness experience and end of life (EOL) concerns. Support network member interviews focused on the relationship of the interviewee with the patient and EOL conversations. Six authors independently coded transcripts and jointly conducted qualitative thematic analysis. 72 total interviews (13 patients, 12 informal caregivers, 6 CM practitioners, and 4 physicians) revealed two themes. (1) Staying positive was a primary patient coping mechanism. (2) Patients’ language barriers and socioeconomic and immigration status posed challenges in participants’ illness experience. Appropriately addressing language barriers and social context during medical visits is crucial for effective EOL care. Clinicians should consider patients’ financial constraints and ensure support in applying for public benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

United States Census Bureau. Hispanic heritage month 2018. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2018/hispanic-heritage-month.html. Accessed 14 June 2019.

Pew Research Center. Facts on US Latinos, 2015. https://www.pewhispanic.org/2017/09/18/facts-on-u-s-latinos-current-data/. Accessed 14 June 2019.

Lauderdale DS, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Kandula NR. Immigrant Perceptions of Discrimination in Health Care: the California Health Interview Survey 2003. Med Care. 2006;44(10):914–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000220829.87073.f7.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003.

2017 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2018. AHRQ Pub. No. 18-0033-EF.

Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.9468.

Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in the latino population. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxp008.

Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O 2nd. Defining cultural competence: practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/118.4.293.

Center for Immigration Studies. Immigrants in the United States: A Profile of America's Foreign-Born Population. https://cis.org/Immigrants-United-States-Profile-Americas-ForeignBorn-Population. Accessed 14 June 2019.

Pew Research Center. Hispanic Immigrants more likely to Lack Health Insurance than U.S.-Born. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/09/26/higher-share-of-hispanic-immigrants-than-u-s-born-lack-health-insurance/. Accessed 14 June 2019.

United States Census Bureau. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-263.html. Accessed 14 June 2019.

National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health of White non-Hispanic population. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/white-health.htm. Accessed 14 June 2019.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2018–2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. 2018. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-hispanics-and-latinos/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-hispanics-and-latinos-2018-2020.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2019.

Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(6):923–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0402.

Chen L, Li CI. Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1666–722. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0293.

Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, Sun P, Narod SA. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(2):165–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.17322.

Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Ell K, Palinkas L. Navigating the advanced cancer experience of underserved Latinas. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(12):3095–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1437-4.

Pérez-Stable EJ, Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R, Hiatt RA, McPhee SJ. Misconceptions about cancer among Latinos and Anglos. JAMA. 1992;268(22):3219–23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03490220063029.

Castillo A, Mendiola J, Tiemensma J. Emotions and Coping Strategies During Breast Cancer in Latina Women: A Focus Group Study. Hisp Health Care Int. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540415319837680.

Carrion IV, Nedjat-Haiem F, Macip-Billbe M, Black R. "I Told Myself to Stay Positive" perceptions of coping among Latinos with a cancer diagnosis living in the United States. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(3):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115625955.

Leyva B, Allen JD, Tom LS, Ospino H, Torres MI, Abraido-Lanza AF. Religion, fatalism, and cancer control: a qualitative study among Hispanic Catholics. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(6):839–49. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.38.6.6.

Flórez KR, Aguirre AM, Viladrich A, Céspedes A, De La Cruz AA, Abraido-Lanza AF. Fatalism or destiny? A Qualitative Study and Interpretative Framework on Dominican Women's Breast Cancer Beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(4):291–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-008-9118-6.

Lee MM, Lin SS, Wrensch MR, Adler SR, Eisenberg D. Alternative therapies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(1):42–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/92.1.42.

Owens B. A test of the self-help model and use of complementary and alternative medicine among hispanic women during treatment for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(4):42. https://doi.org/10.1188/07.ONF.E42-E50.

Owens B, Jackson M, Berndt A. Complementary therapy used by Hispanic women during treatment for breast cancer. J Holist Nurs. 2009;27(3):167–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010108330801.

Rush CL, Lobo T, Serrano A, Blasini M, Campos C, Graves MD. Complementary and alternative medicine use and Latina breast cancer survivors’ symptoms and functioning. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2016;4(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4040080.

Lockhart JS, Oberleitner MG, Nolfi DA. The Asian immigrant cancer survivor experience in the United States: a scoping review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(3):177–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000797.

Wang JH, Adams IF, Tucker-Seeley R, Gomez SL, Allen L, Huang E, Wang Y, Pasick RJ. A mixed method exploration of survivorship among Chinese American and non-Hispanic White breast cancer survivors: the role of socioeconomic well-being. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(10):2709–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0347-0.

Yi EG. Does acculturation matter? End-of-life care planning and preference of foreign-born older immigrants in the United States. Innov Aging. 2019;3(2):igz012. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz012.

Jaramillo S, Hui D. End-of-life care for undocumented immigrants with advanced cancer: documenting the undocumented”. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;51(4):784–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.009.

Coyne JC, Pajak TF, Harris J, Konski A, Movsas B, Ang K, Watkins BD. Emotional Well-being does not Predict Survival in Head and Neck Cancer Patients: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Atudy. Cancer. 2007;110(11):2568–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23080.

Nakaya N, Bidstrup PE, Saito-Nakaya K, Frederiksen K, Kosenvuo M, Pukkala E, Kaprio J, Floderus B, Uchitomi Y, Johansen C. Personality traits and cancer risk and survival based on Finnish and Swedish Registry Data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):377–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq046.

Silva MD, Genoff M, Zaballa A, Jewell S, Stabler S, Gany FM, Diamond LC. Interpreting at the end of life: a systematic review of the impact of interpreters on the delivery of palliative care services to cancer patients with limited English proficiency. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;51(3):569–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.011.

Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Kerr K, O’Riordan D, Pantilat SZ. Interpretation for discussions about end-of-life issues: results from a National Survey of Health Care Interpreters. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(9):119–1026. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0032.

Garcia ME, Bindman AB, Coffman J. Language-concordant primary care physicians for a diverse population: the view from California. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):343–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2019.0035.

Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and it effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2016;122(8):283–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29808.

Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, Newcomb P. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620.

Blinder V, Eberle C, Patil S, Gany FM, Bradley CJ. Women with breast cancer who work for accommodating employers more likely to retain jobs after treatment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(2):274–81. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1196.

Pallok K, De Maio F, Ansell DA. Structural racism—a 60-year-old Black Woman with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(16):1489–93. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1811499.

Hansen H, Metzl J. Structural competency in the U.S. Healthcare crisis: putting social and policy interventions into clinical practice. J Bioeth Inq. 2016;13(2):179–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-016-9719-z.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the study participants from Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and the Charlotte Maxwell Clinic and their informal and professional caregivers for generously sharing their experiences with us. We also offer special thanks to the staff and volunteers of CMC, as well as Julissa Cabrera, BA, one of the UCSF interviewers. This work was supported by a grant from Susan G. Komen for the Cure (DISP0707207; Adler, PI). The participation of Johanna Glaser, BA, and Ariana Thompson-Lastad, PhD, was supported by the UCSF Osher Center research training fellowship program (NCCIH T32 AT003997; Hecht and Adler, MPIs). Two concomitant studies that informed the conduct of this research were funded by the National Institutes of Health (R21 009363; Adler, PI) and the California Breast Cancer Research Program (13BB-1000; Adler and Stone, MPIs).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Glaser, J., Coulter, Y.Z., Thompson-Lastad, A. et al. Experiences of Advanced Breast Cancer Among Latina Immigrants: A Qualitative Pilot Study. J Immigrant Minority Health 22, 1287–1294 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01069-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01069-4