Abstract

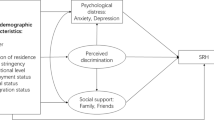

With a research focus on the possible impact of perceived discrimination on physical symptoms, this study examined a moderated mediation model that depressive symptoms would mediate the association between perceived discrimination and physical symptoms, and family satisfaction would show moderating effects on both depressive and physical symptoms among immigrants. Immigrant women from Mainland China into Hong Kong (N = 966) completed a cross-sectional survey. Depressive symptoms mediated the association between perceived discrimination and physical symptoms. Family satisfaction moderated the association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms that participants with lower family satisfaction showed a stronger association. However, family satisfaction did not moderate with perceived discrimination or depressive symptoms to predict physical symptoms. Our findings demonstrated the health consequences of perceived discrimination. Development of resilience programs, particularly with a focus of strengthening family resources, may in tandem help immigrants manage their experiences with discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Card D. Immigration and inequality. Am Econ Rev. 2009;99:1–21.

Schneider SL. Anti-immigrant attitudes in Europe: outgroup size and perceived ethnic threat. Eur Sociol Rev. 2008;24:53–67.

Jordan LP, Graham E. Resilience and well-being among children of migrant parents in South-East Asia. Child Dev. 2012;83:1672–88.

Zheng Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in migrant Indians in an urbanized society in Asia: The Singapore Indian eye study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2119–244.

Montreuil A, Bourhis RY. Acculturation orientations of competing host communities toward valued and devalued immigrants. Int J Intercult Relat. 2004;28:507–32.

Chae DH, et al. Unfair treatment, racial/ethnic discrimination, ethnic identification, and smoking among Asian Americans in the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:485–92.

American Psychological Association: Stress and health disparities: contexts, mechanisms, and interventions among racial/ethnic minority and low-socioeconomic status populations. 2017; https://www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/stress-report.aspx. Accessed 4 May 2018.

Ames ME, Leadbeater BJ. Depressive symptom trajectories and physical health: persistence of problems from adolescence to young adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:121–9.

Demyttenaere K, et al. Comorbid painful physical symptoms and depression: prevalence, work loss, and help seeking. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:185–93.

Yu NX, et al. Resilience and depressive symptoms in mainland Chinese immigrants to Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:241–9.

Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:531–54.

Kim JA, et al. Predictive factors of depression among Asian female marriage immigrants in Korea. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13:275–81.

Wong DFK, Song HX. Dynamics of social support: a longitudinal qualitative study on mainland Chinese immigrant women's first year of resettlement in Hong Kong. Social Work Ment Health. 2006;4:83–101.

Cheuk-lam P. The prejudicial portrayal of immigrant families from Mainland China in Hong Kong media. In: Kwok-bun C, editor. International handbook of Chinese Families. Springer: New York; 2013. p. 211–227.

Law K-y, Lee K-m. Citizenship, economy and social exclusion of mainland Chinese immigrants in Hong Kong. J Contemp Asia. 2006;36:217–42.

Census and Statistics Department: Thematic report: Ethnic minorities. 2016 Population by-census. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2017.

Census and Statistics Department: Thematic report: Persons from the Mainland having resided in Hong Kong for less than 7 years. 2016 Population by-census. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2018.

Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong monthly digest of statistics (Jan 2018). Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2018.

Home Affairs Department: Statistics on new arrivals from the Mainland (Fourth quarter of 2017). Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2017.

Schmitt MT, et al. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:921.

Carliner H, et al. Racial discrimination, socioeconomic position, and illicit drug use among US Blacks. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:551–60.

Visser MJ, et al. Perceived ethnic discrimination in relation to smoking and alcohol consumption in ethnic minority groups in The Netherlands: the HELIUS study. Int J Public Health. 2017;62:879–87.

Williams DR, et al. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:441–52.

Schulz AJ, et al. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1265–70.

Gibbons FX, et al. Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: a differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychol. 2014;33:11–9.

Borrell LN, et al. Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1415–27.

Harris R, et al. Racism and health: the relationship between experience of racial discrimination and health in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1428–41.

Black LL, Johnson R, VanHoose L. The relationship between perceived racism/discrimination and health among Black American women: a review of the literature from 2003–2013. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2:11–20.

Lee S, Kleinman A. Are somatoform disorders changing with time? The case of neurasthenia in China. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:846–9.

Novick D, et al. Which somatic symptoms are associated with an unfavorable course in Asian patients with major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2013;149:182–8.

Shek DTL, Liang LY. Psychosocial factors influencing individual well-being in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong: a six-year longitudinal study. Appl Res Qual Life. 2018;13:561–84.

Wu MH, Chang SM, Chou FH. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of filial piety and depression in older people. J Transcult Nurs. 2018;29:369–78.

Chae DH, et al. Discrimination, family relationships, and major depression among Asian Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:361–70.

Chou K-L. Perceived discrimination and depression among new migrants to Hong Kong: the moderating role of social support and neighborhood collective efficacy. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:63–70.

Ng IFS, et al. Effects of perceived discrimination on the quality of life among new mainland Chinese immigrants to Hong Kong: a longitudinal study. Soc Indic Res. 2015;120:817–34.

Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:888–901.

Gilbert PA, Zemore SE. Discrimination and drinking: a systematic review of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:178–94.

Leung GM, et al. Cohort profile: FAMILY Cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;46:e1.

Census and Statistics Department: Hong Kong 2011 population census—summary results. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2012.

Ngo H. The economic role of immigrant wives in Hong Kong. Int Migr. 1994;32:403–23.

Noh S, Kaspar V, Wickrama KA. Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: preliminary findings for Korean immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1269–74.

Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:232–8.

Spitzer RL, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44.

Chan DH, Ho SC, Donnan SPB. A survey of family APGAR in Shatin private ownership homes. Hong Kong Pract. 1988;10:3295–9.

Nan H, et al. Effects of depressive symptoms and family satisfaction on health related quality of life: The Hong Kong FAMILY study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58436.

Department of Health, Department of Community Medicine, The University of Hong Kong: Population Health Survey 2003/2004. Department of Health: Hong Kong; 2005.

Ho LM, et al. Changes in individual weight status based on body mass index and waist circumference in Hong Kong Chinese. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119827.

Cheung YTD, et al. Who wants a slimmer body? The relationship between body weight status, educational level and body shape dissatisfaction among young adults in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:835.

Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2005;89:852–63.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Publications, Inc; 2013.

Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991.

Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31:437–48.

Bernstein KS, et al. Acculturation, discrimination and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in New York City. Commun Ment Health J. 2011;47:24–34.

Kleinman A. Culture and depression. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:951–3.

Goldenberg DL. Pain/depression dyad: a key to a better understanding and treatment of functional somatic syndromes. Am J Med. 2010;123:675–82.

Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:774.

Fischer AH, Manstead ASR. The relation between gender and emotions in different cultures. Gender Emot Soc Psychol Perspect. 2000;1:71–94.

Tang CSK, Chua Z. A gender perspective on Chinese social relationships and behavior. In: Bond MH, editor. Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 533–553.

Li J, Xu L, Chi I. Challenges and resilience related to aging in the United States among older Chinese immigrants. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22:1548–55.

Salas-Wright CP, et al. Substance use disorders among immigrants in the United States: a research update. Addict Behav. 2018;76:169–73.

Leung HC, Lee KM. Immigration controls, life-course coordination, and livelihood strategies: a study of families living across the Mainland-Hong Kong border. J Fam Econ Issues. 2005;26:487–507.

Hsiao C, Ching HS. WSK: A panel data approach for program evaluation: measuring the benefits of politcal and economic integration of Hong Kong with Mainland China. J Appl Econ. 2012;27:705–40.

Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38:922–34.

Yu NX, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial to decrease adaptation difficulties in Chinese new immigrants to Hong Kong. Behav Ther. 2014;45:137–52.

Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Psychological resilience, pain catastrophizing, and positive emotions: perspectives on comprehensive modeling of individual pain adaptation. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:317.

Janzen B, et al. Racial discrimination and depression among on-reserve First Nations people in rural Saskatchewan. Can J Public Health. 2018;108:e482–e487487.

Hurd NM, et al. Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1910–8.

Assari S, Watkins DC, Caldwell CH. Race attribution modifies the association between daily discrimination and major depressive disorder among blacks: the role of gender and ethnicity. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2:200–10.

Slotman A, Snijder MB, Ikram UZ, Schene AH, Stevens GW. The role of mastery in the relationship between perceived ethnic discrimination and depression: The HELIUS study. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2017;23:200.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust, the sole funder of the FAMILY Project from 2007 to 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, N.X., Ni, M.Y. & Stewart, S.M. A Moderated Mediation Analysis on the Association Between Perceived Discrimination and Physical Symptoms Among Immigrant Women from Mainland China into Hong Kong: Evidence from the FAMILY Cohort. J Immigrant Minority Health 23, 597–605 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01042-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01042-1