Abstract

This paper’s aim is to propose a mediation framework and test whether lifestyle choices and social capital are pathways through which baseline levels of well-being affect subsequent physical health among older adults. Using large-scale panel data for Australia, we find that past levels of well-being have strong direct effects on present physical health. We also show that more frequent socialization and more frequent participation in physical activity are two pathways through which higher levels of well-being lead to better physical health. These mediating effects vary across gender. Our findings highlight a protective role of subjective well-being in physical health. Interventions taking into account not only the direct but also the indirect effects of well-being are promising avenues for physical health maintenance in the older population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A related strand of literature shows that personality traits affect how people react to life events (e.g. Boyce et al., 2010; Buddelmeyer and Powdthavee, 2016; Kesavayuth et al., 2016); and that hedonic adaptation may occur over time (Boyce and Wood, 2011; Magnani and Zhu, 2018; Oswald and Powdthavee, 2008).

Like Ohrnberger et al. (2017), we use physical activity, social interaction and smoking as possible mediators, but also consider additional pathways: participation in volunteer activities, and whether the individual is an active member of a social club.

These are the only waves which collected data on all three types of well-being measures used in this study.

It might be wondered what would happen if any of these four components is omitted. To this end, we dropped each component separately, and found that doing so brings down Cronbach’s alpha. In other words, using all four components provides a more reliable physical health measure.

The base year is 2012.

A variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis indicated that potential multicollinearity was not an issue regarding the choice of explanatory variables.

Note that the initial condition of physical health, \({P}_{i,t=0}\), captures early life investments and health endowments.

All estimates are significant at a p-value < 0.01 or stricter, as indicated in the table.

Significance of the indirect effect can be tested using the Sobel test (Krull and MacKinnon, 2001; Sobel, 1982). This test has been specifically developed for mediation analysis, and allows us to examine whether the effect of baseline levels of well-being operates through each of the possible mediators.

For example, there are gender differences in health behaviors which may stem from perceptions about ‘maleness’ leading to a greater willingness to take risks (Courtenay, 2000).

References

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Hypertension and happiness across nations. Journal of Health Economics, 27(2), 218–233.

Boyce, C. J., Wood, A. M., & Brown, G. D. A. (2010). The dark side of conscientiousness: Conscientious people experience greater drops in life satisfaction following unemployment. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 535–539.

Boyce, C. J., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Personality prior to disability determines adaptation: Agreeable individuals recover lost life satisfaction faster and more completely. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1397–1402.

Buddelmeyer, H., & Powdthavee, N. (2016). Can having internal locus of control insure against negative shocks? Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 122, 88–109.

Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A Practitioner’s Guide to Cluster-Robust Inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., Kassenboehmer, S. C., & Schurer, S. (2014). Healthy habits: The connection between diet, exercise, and locus of control. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 98, 1–28.

Cohen, S., Gottlieb, B. H., & Underwood, L. G. (2000). Social relationships and health. In Cohen, S., Underwood, L. G., & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 3–25). New York: Oxford.

Contoyannis, P., & Li, J. (2011). The evolution of health outcomes from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Health Economics, 30(1), 11–32.

Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Behavioral factors associated with disease, injury, and death among men: Evidence and implications for prevention. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 9(1), 81–142.

Danaei, G., Ding, E. L., Mozaffarian, D., Taylor, B., Rehm, J., Murray, C. J., & Ezzati, M. (2009). The preventable causes of death in the United States: Comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med, 6(4).

Diener, E., Pressman, S. D., Hunter, J., & Delgadillo-Chase, D. (2017). If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 9(2), 133–167.

Dour, H. J., Wiley, J. F., Roy-Byrne, P., Stein, M. B., Sullivan, G., Sherbourne, C. D., & Craske, M. G. (2014). Perceived social support mediates anxiety and depressive symptom changes following primary care intervention. Depression and Anxiety, 31(5), 436–442.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11176–11183.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2018). Economics of Happiness. Berlin: Springer.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

Goldsmith, D. J., & Albrecht, T. L. (2011). Social support, social networks, and health. In T. L. Thompson, R. L. Parrott, & J. F. Nussbaum (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of health communication (2nd ed., pp. 335–348). New York: Routledge.

Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy, 80(2), 223–255.

Grossman, M. (2000). The human capital model. Part A of Handbook of Health Economics, vol. 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 347–408 (Chapter 7).

Hemingway, H., Nicholson, A., Stafford, M., Roberts, R., & Marmot, M. (1997). The impact of socioeconomic status on health functioning as assessed by the SF-36 questionnaire: The Whitehall II Study. American Journal of Public Health, 87(9), 1484–1490.

Holstila, A., Rahkonen, O., Lahelma, E., & Lahti, J. (2016). Changes in leisure-time physical activity and subsequent sickness absence due to any cause, musculoskeletal, and mental causes. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(8), 867–873.

Hurley, S. F. (2005). Short-term impact of smoking cessation on myocardial infarction and stroke hospitalisations and costs in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 183(1), 13–17.

Isen, A. M. (2000). Positive affect and decision making. In M. Lewis & J. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 417–435). New York: Guilford.

Kesavayuth, D., Liang, Y., & Zikos, V. (2018). An active lifestyle and cognitive function: Evidence from China. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 12, 183–191.

Kesavayuth, D., Poyago-Theotoky, J., Tran, D. B., & Zikos, V. (2020). Locus of control, health and healthcare utilization. Economic Modelling, 86, 227–238.

Kesavayuth, D., Rosenman, R. E., & Zikos, V. (2016). Retirement, personality, and well-being. Economic Inquiry, 54(2), 733–750.

Kesavayuth, D., Shangkhum, P., & Zikos, V. (2021). Subjective well-being and healthcare utilization: A mediation analysis. SSM-Population Health, 14, 100796.

Kesavayuth, D., & Zikos, V. (2018). Happy people are less likely to be unemployed: Psychological evidence from panel data. Contemporary Economic Policy, 36(2), 277–291.

Krull, J. L., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2001). Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36(2), 249–277.

Magnani, E., & Zhu, R. (2018). Does kindness lead to happiness? Voluntary activities and subjective well-being. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 77, 20–28.

Mishra, V., & Smyth, R. (2014). It pays to be happy (if you are a man): Subjective wellbeing and the gender wage gap in Urban China. International Journal of Manpower, 35(3), 392–414.

Mokdad, A. H., Marks, J. S., Stroup, D. F., & Gerberding, J. L. (2005). Correction: Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA, 293(3), 293–294.

Murray, C. J., Lauer, J. A., Hutubessy, R. C., Niessen, L., Tomijima, N., Rodgers, A., & Evans, D. B. (2003). Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: A global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk. The Lancet, 361(9359), 717–725.

Nikolaev, B. (2018). Does higher education increase hedonic and eudaimonic happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(2), 483–504.

O’Connor, K. J., & Graham, C. (2019). Longer, more optimistic, lives: Historic optimism and life expectancy in the United States. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 168, 374–392.

Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E., & Sutton, M. (2017). The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 195, 42–49.

Oswald, A. J., & Powdthavee, N. (2008). Does happiness adapt? A longitudinal study of disability with implications for economists and judges. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5–6), 1061–1077.

Ryff, C. D., Radler, B. T., & Friedman, E. M. (2015). Persistent psychological well-being predicts improved self-rated health over 9–10 years: Longitudinal evidence from MIDUS. Health Psychology Open, 2(2), 1–11.

Scrivens, K., & Smith, C. (2013). Four Interpretations of Social Capital: An Agenda for Measurement, OECD Statistics Working Papers. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/four-interpretations-of-social-capital_5jzbcx010wmt-en.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet, 385(9968), 640–648.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.P. (2010). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress, Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

Tran, D. B., Pham, T. D. N., & Nguyen, T. T. (2021). The influence of education on women’s well-being: Evidence from Australia. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0247765.

Umberson, D., Crosnoe, R., & Reczek, C. (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157.

United Nations (2017). World Population Ageing 2017: Highlights. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf. Accessed on 9.2.2020.

VanderWeele, T. J. (2016). Mediation analysis: A practitioner’s guide. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 17–32.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2012). The HILDA Survey: A case study in the design and development of a successful Household Panel Survey. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 3(3), 369–381.

Wright, K. (2016). Social networks, interpersonal social support, and health outcomes: A health communication perspective. Frontiers in Communication, 1, 10.

Xu, J., & Roberts, R. E. (2010). The power of positive emotions: It’s a matter of life or death – Subjective well-being and longevity over 28 years in a general population. Health Psychology, 29(1), 9–19.

Yanek, L. R., Kral, B. G., Moy, T. F., Vaidya, D., Lazo, M., Becker, L. C., & Becker, D. M. (2013). Effect of positive well-being on incidence of symptomatic coronary artery disease. The American Journal of Cardiology, 112(8), 1120–1125.

Zhu, R. (2016). Retirement and its consequences for women’s health in Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 163, 117–125.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Stephanie Rossouw (the Editor), Olga Popova (the Associate Editor), and two anonymous referees. This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and was funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either FaHCSIA or the Melbourne Institute. Zikos acknowledges financial support from the Faculty of Economics, Chulalongkorn University, under its grant scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

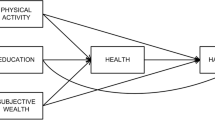

See Fig. 1 and Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kesavayuth, D., Shangkhum, P. & Zikos, V. Well-Being and Physical Health: A Mediation Analysis. J Happiness Stud 23, 2849–2879 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00529-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00529-y