Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate potential reciprocal relationships between entrepreneurs’ personal resources—namely, positive orientation—work engagement, and entrepreneurial success. We also investigated stability/change in the levels of these variables over time. We collected data from a sample of entrepreneurs using a longitudinal field study design with three measurement times, at 7-month intervals. The results confirm reciprocal relationships between positive orientation as well as work engagement and entrepreneurial success, evaluated in comparison with other businesses in the same sector and region. Entrepreneurs’ positive orientation predicts their evaluation of entrepreneurial success over time, and vice versa—entrepreneurs who experience successes develop their personal resources and work engagement. Upward spirals, consisting in an increase in the variables over time, were not detected. The understanding of the ways in which entrepreneurs’ personal resources foster the success of their firms, and vice versa, helps to advance the psychological explanation of entrepreneurship. This knowledge may inform training strategies employed by practitioners supporting entrepreneurs and potentially reduce the costs associated with the collapse of businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The good condition of businesses and their successful functioning is of great societal importance, as entrepreneurial activity provides not only financial benefits and innovative solutions but also employment for a large part of the working population (Muller et al. 2015; van Praag and Versloot 2007). It is therefore vital to gain insight into mechanisms related to entrepreneurial success—and it is not only economic but also psychological mechanisms that may play a prominent role here (Baron 2007; Rauch and Frese 2007; Razmus and Laguna 2018).

There is growing evidence that the personal characteristics of the entrepreneur are of great significance for entrepreneurial success (Rauch and Frese 2007). Most previous studies, however, focused on static, trait-like phenomena in entrepreneurship, and there is a vital call for explanations of the dynamic mechanisms responsible for entrepreneurial activity (Shepherd 2015). There is also a need to find stronger evidence of the relationships between entrepreneurs’ characteristics and performance and to explore the intervening processes more carefully (Stephan 2018).

Our research answers these calls as it tests the dynamic relationships between entrepreneurs’ personal resources, work engagement, and their evaluation of business success. More specifically, we would like (1) to test the potential reciprocal relationships between these variables and (2) to look for stability/change in their levels, using a longitudinal study design. The conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2011) and the positive orientation theory (Caprara et al. 2009, 2012) provide the foundation for our study. They allow us to focus on positive psychological mechanisms as well as to investigate the dynamic processes that operate over time and may foster the experience of entrepreneurial success. Both theories postulate that the key personal resource is the individual’s personal attitude towards the world—more specifically, a positive view of themselves, life, and the future as well as regarding events as predictable and generally occurring in their best interest (Caprara et al. 2009, 2012; Hobfoll 1989). It not only serves as a resistance resource but may also enable engagement in activity (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008) and success in it (Laguna 2018). In this study, we examine the relationships emerging over time, providing a new insight into entrepreneurial success mechanisms.

In the subsequent sections of the present paper, we first explain in more detail our general theoretical framework. Next, we explain how we understand entrepreneurial success. Finally, we specify the postulated relationships between work engagement and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success, as well as between positive orientation and work engagement and success.

1.1 Personal Resources in Explaining Work Engagement and Entrepreneurial Success

As work is an important life domain that provides resources and at the same time drains them, we refer to the COR theory (Hobfoll 1989), which has become vital in the field of positive psychology in recent years (Hobfoll 2011). It can be applied to explain relationships between personal resources, work engagement (Gorgievski et al. 2011), and success in entrepreneurial activity. Firstly, it postulates that the depletion of valuable resources will be accompanied by impaired psychological well-being (Hobfoll 1989, 2011), thus having an inhibitory impact on work engagement (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008) and, in consequence, on success in activity. A decrease in personal resources may prompt efforts to conserve other resources (e.g., energy); as a result, entrepreneurs may withdraw from engagement in their demanding work and thus decrease the performance of their businesses. Conversely, a high level of personal resources may stimulate positive affect, activity engagement, and performance (Laguna 2018). The COR theory also postulates that people have to invest their resources in order to prevent resource loss and gain more resources (Hobfoll 1989, 2011). In the work context, such resource investment boosts engagement in resource gain processes (e.g., accumulation of money). Consequently, entrepreneurs who have rich resources, including personal, will be more capable of sustaining work engagement and increasing the performance of their businesses than those who lack resources (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008).

What is important, the COR theory explains loss and gain cycles and spirals, which are of interest in our study. These cycles/spirals move with amplified strength when people either lose the resources they need to meet challenges (loss spiral) or acquire resources (gain spiral) allowing them to risk looking for new challenges (Hobfoll 2011). Especially gain cycles/spirals, which have received considerably less attention than loss spirals, are critical to work engagement and success. Gain cycles may form spirals, as people experiencing resource gains experience higher well-being and are more ready to undertake further investment of resources to sustain resource gains, enhance the speed of the engagement process, and increase further resource gains (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008). Similar gain spirals concerning relationships between resources and positive emotions are postulated by the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson 2013).

Moreover, Hobfoll (1989) highlights that it is important to investigate not only the effect of resources on performance and other outcomes, but also the effect of these outcomes on resources. This suggests the need to investigate reciprocal relationships between personal resources and other variables, such as work engagement and entrepreneurial success.

1.2 Entrepreneurial Success

Regarding the definitions of entrepreneurial success, the economic literature suggests that the financial performance of the firm is central; however, entrepreneurs themselves hold diverse views of success (Wach et al. 2016). The definition of entrepreneurial success is inevitably connected with the way in which it is operationalized and approached in research (Razmus and Laguna 2018). As business performance may be different in different industry sectors and in different regional markets, researchers use two strategies to control for these differences. One is to focus on a specific sector and region to obtain comparable success indicators (e.g., Baum and Locke 2004). However, this narrows the generalizability of results. The second strategy is to use a subjective evaluation of success, with the recommendation to base this performance assessment on comparison with the performance of other business, including competitors. This method provides comparable results from different industries (Wach et al. 2016; Wiklund 1999). This second strategy is preferred even over objective ratings of performance, as they may suffer from imprecision and unreliability, being more context-dependent than ratings provided by entrepreneurs (Sturman 2007). Such success criteria are proposed in many theoretical analyses, as comparison with other businesses offers more balanced evaluation of results obtained by a specific firm (Baron 2007; Gielnik and Frese 2013). Moreover, subjective evaluations of business success are often better predictors of entrepreneurs’ decisions and behaviors than objective indicators (Dijkhuizen et al. 2017). Based on all these recommendations, we evaluate business success in terms of comparison with similar organizations in the same sector and region, taking market share and sales turnover into account.

Many firms, especially small ones, are run by the person who established them. Establishing and managing a firm are both treated as behavioral criteria of entrepreneurship, allowing us to distinguish entrepreneurs from managers and business owners who do not manage their own firms (Baron 2007; Baron et al. 2012). In cases when both of these criteria are fulfilled, i.e., when a person is an owner and a manager of a business, the success of the business is, at least to some extent, dependent on the activity of the entrepreneur—business owner—and on their personal characteristics (Rauch and Frese 2007).

Research on entrepreneurial success, similarly to research on job performance, is predominantly static in nature, mostly examining the correlates of various performance ratings, with the assumption that the results would generalize to any other point in time. Yet, research using a dynamic performance approach brings abundant evidence that individuals’ job performance does indeed change with time (for a review see Sturman 2007). The same is postulated by the COR theory (Gorgievski et al. 2011), but it is hardly ever tested, especially in the case of entrepreneurs. Research on the dynamic mechanisms stimulating entrepreneurial success is needed to uncover the ways in which it is related to work engagement and entrepreneurs’ personal resources.

1.3 Work Engagement and Entrepreneurial Success

To achieve success, one must first undertake an activity and be engaged in it until a good result is achieved, as activity engagement is a prerequisite of performance. In the work context, the concept of work engagement was proposed, defined as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al. 2002, p. 74). It serves motivational functions in employees and is confirmed to be related to many positive individual and organizational outcomes, including employees’ health and well-being (Llorens et al. 2007; Schaufeli 2013). There is also empirical evidence that employees’ work engagement is positively related to their performance (for a review see: Bailey et al. 2015; Schaufeli 2013).

The relationship between work engagement and business success may be also positive in the case of entrepreneurs, but this is less obvious. Entrepreneurial success may be dependent not only on entrepreneurs’ work engagement but also on external factors, such as market conditions or capital availability (Wiklund 1999). They work in less controlled settings, in a demanding environment, in which the results of individual activity may also depend on contextual factors (Dijkhuizen et al. 2016). Although there is some evidence that the work engagement of self-employed people and business owners is related to their performance (e.g., Gorgievski et al. 2014) and subjective evaluation of their business success (Dijkhuizen et al. 2017), the engagement-entrepreneurial success relationship awaits further investigation.

What is also far from obvious is the potential opposite direction in engagement–success relationship (Dijkhuizen et al. 2017). It is possible that when a person achieves success in action, this serves as positive feedback and strengthens their motivation and engagement, as is postulated by the COR theory describing gain cycles (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008). Entrepreneurs experiencing some resource gains thanks to the success of their firms may be more ready to invest resources and sustain their engagement to increase further resource gains. Based on this, we can hypothesize positive cross-lagged effects between work engagement and entrepreneurial success.

1.4 Personal Resources and Work Engagement

The COR theory postulates that people have to invest their resources to prevent resource loss and to gain more resources (Hobfoll 1989, 2011). When describing the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between individual characteristics and organizational outcomes, researchers have stressed the role of personal resources (Xanthopoulou et al. 2009a, b). The investment of personal resources may boost engagement in resource gain; consequently, people with rich resources will sustain their work engagement (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008).

We focus on one of personal resources—positive orientation, a higher order construct that captures the core of self-esteem, life satisfaction, and optimism (Caprara et al. 2009, 2012). The central thesis of the positive orientation theory is that viewing oneself, life, and the future positively is a basic predisposition making people able to welcome opportunities and to cope with life, despite adversities and hardships. It is postulated that positive orientation enables individuals to “fully express their potentials and to fully benefit from contingent opportunities” (Caprara et al. 2009, p. 283). As personal resources, together with job resources, are important factors stimulating work engagement (Halbesleben 2010), positive orientation also plays this role. The beliefs-affect-engagement model explains the mechanism through which positive orientation may stimulate behavior—it fuels positive affect, which in turn fosters activity engagement (Laguna 2018). Indeed, it is proven that positive orientation is related to work engagement in employees (Alessandri et al. 2015a). There is also some evidence that it plays a motivational role in entrepreneurs, helping them to invest energy in activity and sustaining their goal realization efforts (Laguna et al. 2016).

The COR theory also provides some grounds to expect reversed relationships, leading from work engagement to personal resources (Hobfoll 1989). Therefore, we intend to analyze the reciprocal relationships between positive orientation and work engagement (Laguna 2018). No direct evidence concerning positive orientation is available; however, longitudinal studies show that work engagement increases employees self-efficacy beliefs over time (Llorens et al. 2007). As self-efficacy beliefs, being a distinct construct, are correlated with positive orientation (Oleś et al. 2013), we can expect similar mechanisms linking positive orientation and work engagement. Thus, based on the available theoretical explanations and previous research findings, we expect positive reciprocal relationships between positive orientation and work engagement.

1.5 Personal Resources and Entrepreneurial Success

Positive orientation is one of personal resources which can be spent to obtain other resources, such as success in business performance or financial returns. It is postulated by Hobfoll (2002) that people do not only preserve their resources but also tend to accumulate them, and personal resources are expected to be positively related to performance. Indeed, there are studies showing that employees’ psychological capital (i.e., positive beliefs, including optimism) may have a positive financial impact and result in a high return on investment (Luthans et al. 2006). However, there are also studies showing that personal resources do not play a role in explaining an organization’s financial returns (Xanthopoulou et al. 2009b). This suggests that more research is needed to test the relationship between personal resources and business performance.

As positive orientation is the “modes of viewing self, life, and future, through which people welcome opportunities, cope with adversities, and ultimately chart the course of their life” (Caprara et al. 2009, p. 283), it may lead to higher performance (Laguna 2018). There is some evidence that positive orientation predicts in-role and extra-role performance in employees (Alessandri et al. 2012). Moreover, a study on security agents showed that their positive orientation was related to job performance (Alessandri et al. 2015a). This allows us to expect similar relationships in entrepreneurs and over time. Our expectations are based on research findings showing that entrepreneurs’ positive orientation predicts the realization of their personal goals related to entrepreneurial activity (Laguna et al. 2016) and on a systematic review of research showing that more positive—“happier”—entrepreneurs run higher performing firms (Stephan 2018).

We also postulate the opposite relationship, leading from entrepreneurial success to positive orientation. Despite the fact that genetic research shows that positive orientation is to some degree inherited, it has also been demonstrated that its level may, to some extent, depend on unique personal experience (Caprara et al. 2009, 2018). One sphere of such experience is the effect of the activities of the individual, i.e., the experience of the success or failure of the business that one manages. Successes can make people confident in their abilities, thus increasing their self-esteem, their positive expectations for the future, and their satisfaction with life (Laguna 2018). Although the review of research shows that positive orientation significantly contributes to employees’ job performance (Caprara et al. 2018), we are not aware of research testing the relationships between positive orientation and business success. Our study will therefore provide new insights into these relationships. Based on the above explanations, we expect positive cross-lagged reciprocal relationships between positive orientation and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success.

1.6 Study Aims

The aims of our study were twofold: (1) to test the potential dynamic reciprocal relationships between entrepreneurs’ positive orientation, work engagement, and evaluation of entrepreneurial success; (2) to investigate the stability of or change in the levels of these variables over time, looking for cycles/spirals of resource loss or gain. We decided to test these relationships in a sample of entrepreneurs-business owners in natural, non-experimental settings using a longitudinal study design.

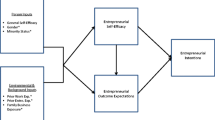

As we have explained above, both directions of relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success are expected. Therefore, rather than a causality model with paths leading from positive orientation to work engagement and then to success, or rather than a reversed causation model with paths leading in the opposite direction, we expect that the cross-lagged model including reciprocal paths will best represent the relationships between the variables in time (see Fig. 1). This is expressed in our hypothesis:

The relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success are reciprocal.

The COR theory (Hobfoll 2011) as well as other theories explaining dynamic mechanisms (e.g., Fredrickson 2013) postulate loss and gain cycles and spirals that move with amplified strength along time. To distinguish these mechanisms, we refer to the explanations offered by Lindsley et al. (1995). They differentiate (a) a reciprocal relationship between variables and (b) a cyclic relationship, i.e., a pattern of consecutive changes in the levels of variables over at least three time points. Reciprocal relationships between variables may, but do not have to, lead to subsequent changes in their level. These changes in the level of each variable may be threefold, consisting in: (1) an increase in each variable over time forming an upward spiral, (2) a decrease of each variable over time forming an downward spiral, or (3) a self-correcting, deviation-counteracting cycle, when a decrease in a variable is followed by its increase, or vice versa (Lindsley et al. 1995). We clearly state that reciprocal relationships are not enough for the detection of upward or downward spirals or deviation-counteracting cycles, and that, to detect such cyclic relationships, at least three measurement times are necessary (Lindsley et al. 1995). This is a very strict distinction of reciprocal and cyclic mechanisms, taking into account that in many studies researchers investigate upward spirals using a study design with two measurement times only.

The explanation of the dynamic mechanism may be even more complex. According to the COR theory, people quickly adapt to circumstances and life events, functioning on an individual baseline level called “dynamic equilibrium” (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008). This dynamic equilibrium is maintained and restored because people develop resource caravans, which are associations of resources that build up across the lifespan and are relatively stable. In consequence, despite temporary changes in the levels of resources that boost engagement and performance at work, a kind of “dynamic stability” (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008) is expected. This suggests that, in the long run, we may not observe changes in the positive orientation level as well as in the levels of work engagement and success. Therefore, both the self-correcting loops and the deviation-amplifying upward spirals may regulate work engagement in entrepreneurs. On the one hand, they may help maintain appropriate levels of resources, work engagement, and company performance (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008); on the other hand, they may prevent overwork and overconfidence, both of which may undermine the ability to manage a business effectively (Hayward et al. 2006). Consequently, instead of a hypothesis, we posed a research question concerning the “dynamic equilibrium” mechanism:

Does the level of each variable increase over time?

2 Method

2.1 Procedure

Entrepreneurs from different regions of Poland were recruited using the snowball sampling method to take part in a longitudinal three-wave field study. There were 7-month intervals between the three measurement times (T1, T2, T3). Such a time interval was chosen based on analysis of the previous studies on work engagement or performance/success in which time lag ranged from three (e.g., Daniels et al. 1997) to 6 months (e.g., Gielnik et al. 2014; Schaufeli et al. 2012) or even 2 years (e.g., Dijkhuizen et al. 2017). We expected that the 7-month time lag will be long enough to observe potential changes in the variables, but not too long to considerably decrease the sample size. All participants fulfilled (jointly) four behavioral criteria of entrepreneurship (Baron 2007; Baron et al. 2012): they were (1) founders, (2) owners, and (3) managers of their businesses, and (4) these businesses had survived on the market for at least 1 year, which means they had moved beyond the start-up phase (Baron 2007).

During the first study wave, the participants provided their contact details, allowing us to ask them to participate in the further stages of the study, at the next two measurement times. We then anonymized the final data set so as to ensure the confidentiality of the data. The participants completed the questionnaires in a paper-and-pencil form. Participation in the study was voluntary and the participants did not receive any reward, apart from the feedback concerning the final research results that was delivered to the entrepreneurs who wished to receive it.

2.2 Participants

Of the initial sample of 206 entrepreneurs (T1), 177 (85.9% of the T1 sample) took part in the second measurement, and 98 (47.6% of the T1 sample) took part in the third measurement. To check if the sample size reduction did not cause selection bias, we tested whether or not the participants who took part in all three measurements (n = 98) differed from those who participated in the study only at T1 (n = 108). The results displayed no statistically significant differences (p > .05) in any of the study variables, in any demographics of the entrepreneurs, or in the characteristics of their firms.

The initial T1 sample consisted of 206 entrepreneurs aged 23–68 (M = 43.81, SD = 11.32), of whom 38.7% were women. Their firms had functioned for between 1 and 46 years (M = 10.11, SD = 8.57), operating in services and trade (155 firms, 75.2%), in production (17 firms, 8.3%), in the construction industry (24 firms, 11.7%), or in other sectors (10 firms, 4.8%). All those firms were small and medium-sized enterprises, employing from 1 to 105 full-time employees (M = 8.6, SD = 17.1), and from 1 to 38 part-time workers (M = 1.9, SD = 4.7). The proportion of women in the sample of entrepreneurs corresponded to the proportion of women in the population, and the characteristics of the businesses matched the population characteristics of enterprises in Poland (Tarnawa and Zadura-Lichota 2013).

2.3 Measures

Positive orientation was measured with the Polish version (Łaguna et al. 2011) of the unidimensional Positivity Scale (Caprara et al. 2012). Its eight items (e.g., “I have great faith in the future”; “I generally feel confident in myself”) were answered on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α ranged between .78 and .83 at the three measurement times. The reliability of all measures administered in each study wave is provided in Table 1.

Work engagement was measured with the Polish version (Chirkowska-Smolak 2012) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). The short nine-item version of the scale contains three dimensions, with three items per dimension, i.e., Dedication (“My work inspires me”); Absorption (“I feel happy when I’m engrossed in my work”); Vigor (“I am bursting with energy in my work”). Answers are given on a 6-point scale (0 = never; 5 = very often). Careful analysis of internal consistency and item–scale correlations shows that, in our sample, item 9 (“I get carried away when I’m working”) has low correlations with the total score and decreases the internal consistency of the scale (from .14 to .22 for the three measurement times, while item–total correlations for all the other items exceed .58), and therefore we excluded it when calculating the total score. In the Polish translation (Chirkowska-Smolak 2012) this item may have two meanings: it may mean either that someone loses track of time when working or that someone forgets about something to be done. In consequence, the Absorption dimension consisted of two items and the whole scale of eight items. Cronbach’s α for the whole scale ranged from .89 to .93 (Table 1).

Entrepreneurial success was measured as an entrepreneur’s evaluation of the performance of his/her business, in comparison with similar businesses in the sector and in the same region. Such comparisons had been used in previous studies and successfully validated as firm performance measure (Wiklund 1999). The scale consisted of three items (“Taking everything into consideration, compared to a similar organization in your industry sector and region, how successful is your business?”; “How does the market share of your business compare to that of similar organizations in your industry sector and region?”; “How does the turnover of your business compare to that of similar organizations in your industry sector and region?”). The items were answered on a 5-point scale (1 = belongs to the less successful half; 2 = successful on average; 3 = belongs to the more successful half; 4 = belongs to the most successful 20%; 5 = belongs to the most successful 5%). Cronbach’s α for the scale ranged from .94 to .95 (Table 1).

2.4 Data Analysis Strategy

Common method variance Prior to hypothesis testing, we checked whether we had indeed captured three distinct constructs (Podsakoff et al. 2012). For this purpose, we performed item-level confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) on data from each measurement time separately (T1, T2, T3). We tested three subsequent models: a single-factor model, in which items of all three scales measuring the study variables were treated as underlying dimensions of a single common latent factor (M1); an uncorrelated factors model, in which the items of each of the three scales were treated as underlying dimensions of a specific latent factor captured by each scale (M2); a correlated factors model, in which these three specific latent factors were allowed to covary with one another (M3). If the single-factor model fitted the data worse than the alternative models at each measurement time, this would confirm the distinct nature of the three constructs.

Measurement invariance To examine the longitudinal measurement invariance of our measurement model, we specified a stability model across measurement times. Its invariance was tested in three steps (Meredith 1993). First, we tested configural invariance by estimating the same model (M1) at the three measurement times, without any cross-group constraints. Next, we specified a more stringent metric invariance model (M2) with equivalent factor loadings across measurement times. Finally, we specified a scalar invariance model (M3), adding equivalent intercepts across measurement times. To examine the differences between these increasingly restricted nested models, we calculated Δχ2 and ΔCFI. The use of Δχ2 in invariance testing has come under criticism because it is highly sensitive to sample size. Consequently, researchers have based decisions concerning invariance on alternative criteria. Cheung and Rensvold (2002) suggested that an absolute difference in CFI lower than .01 would indicate measurement invariance.

Testing of longitudinal models As our data comes from three measurement times, we applied cross-lagged structural equation modeling analysis (Little 2013), which is often chosen for data coming from similar study designs (Hakanen et al. 2008; Laguna et al. 2017; Pitts et al. 1996; Xanthopoulou et al. 2009a). Four alternative longitudinal models were tested successively. First, we tested a stability model (M1) with autocorrelations and synchronous correlations (without cross-lagged paths). The autocorrelations were specified as correlations between error terms corresponding to each latent construct across the three measurement times, and the synchronous correlations were specified as correlations between error terms of the latent constructs measured at the same time. The error terms corresponding to the same indicator over time were allowed to covary with one another, as recommended for longitudinal measurement models (Pitts et al. 1996). Next, we assessed the causality model (M2). In addition to the paths of the stability model, it included cross-lagged structural paths between the study variables. Subsequently, we tested the reversed causation model (M3), including the paths of the stability model and cross-lagged structural paths, reversed to those included in the causality model. Finally, we tested the reciprocal model (M4), containing all the paths included in previous models (M1, M2, and M3), assuming reciprocal relationships between the study variables (see Fig. 1).

Changes in the levels of variables To test whether the level of each variable changed over time, we applied the latent growth curve analysis (Arbuckle 2005; Little 2013). This allowed us to estimate the means and variances for the intercept and the slope of each variable, and the correlation between intercept and slope, allowing us to estimate the latent trends from longitudinal data for each variable.

Analytic approach We used structural equation modeling as the analytic framework. Parameters were estimated by full information maximum likelihood using the AMOS v.22 (Arbuckle 2005). All alternative longitudinal models were first fitted to the data, and then the model with the best fit indices was compared with the three alternative models. Missing data were handled by the Full Information Maximum Likelihood method, allowing the use of all available data from the three study waves, including the participants who only took part in some of the measurements. When interpreting model paths, due to the relatively small sample size, we applied a less restrictive p < .10 value (Cohen 1994).

To assess model fit we used the χ2 goodness-of-fit statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Akaike information criterion (AIC), using the recommended cut-off criteria (Browne and Cudeck 1992; Hu and Bentler 1999; Kline 2005). For RMSEA, values equal to or lower than .05 indicate a good fit, values from .06 to .08 indicate a reasonable fit, and values higher than .10 indicate a poor model fit. For CFI, values of .95 or higher indicate a good fit, values from .90 to .95 indicate a reasonable fit, and values below .90 indicate a poor fit. Lower AIC values indicate better model fit. When testing the differences between the alternative models, we calculated Chi square difference tests (Δχ2) and differences in CFI (ΔCFI; Brown 2006; Kline 2005). A statistically significant difference in χ2, an absolute difference in CFI that is higher than .01, and lower AIC values would indicate a significant difference in model fit.

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

Common method variance We examined a series of measurement models to check for common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2012). At each measurement time, the correlated factors model (M3) showed better fit than the two alternative models: the single common factor model (M1) and the uncorrelated factor model (M2; see Appendix, Table 3). This supports the distinctness of the three latent variables measured in this study, although it shows that they are correlated. The confirmation of their distinctness allows us to reduce the complexity of our hypothesized models by using parcels, taking into account the relatively small sample size (Kline 2005). Therefore, in subsequent analyses we used three work engagement dimensions as indicators of the work engagement latent factor, eight items as indicators of the positive orientation latent factor, and three items as indicators of entrepreneurial success (at each measurement time).

Measurement invariance We tested the longitudinal measurement invariance of our measurement model in three steps. First, configural invariance was supported, as the configural unrestricted model (M1) shows an acceptable fit to the data (Appendix, Table 4). After adding equality constraints on all factor loadings across the measurement times (M2), the model fit did not deteriorate (ΔCFI = .006), indicating full metric invariance (Cheung and Rensvold 2002). In the scalar invariance model (M3), equality constraints were added on all item intercepts. A comparison of this model with the metric invariance model (ΔCFI = .003) indicated full scalar invariance. Based on these results, we can meaningfully analyze the relationships between the constructs across measurement times and compare the mean scores (Meredith 1993).

3.2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means, standard deviations, internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α), and correlations between the variables measured at each of the three measurement times are presented in Table 1. As expected, all variables are positively correlated. The generally moderate test–retest correlations between the three measurement times for each of the study variables demonstrate that they are relatively stable over time.

3.3 Testing of Longitudinal Models

The results of comparisons of four alternative longitudinal models show that only the reciprocal model (M4) had an acceptable fit to the data, as revealed by all fit criteria (χ2(741) = 1181.888, p =.001, CFI = .900, RMSEA = .054, AIC = 1589.888). Neither the stability model (M1; χ2(759) = 1257.832, p =.001, CFI = .887, RMSEA = .057, AIC = 1629.832), nor the causality model (M2; χ(751)v = 1229.412, p =.001, CFI = .891, RMSEA = .056, AIC = 1617.412) or the reversed causation model (M3; χ2(751)= 1219.449, p = .001, CFI = .894, RMSEA = .055, AIC = 1607.449) attained an acceptable fit in terms of all fit criteria.

As all the other models are nested in model M4, it was compared with the other alternative models. Model comparison using the χ2 difference tests showed that model M4 was superior to the three alternative models, with a significantly better fit to the data. For comparisons with M1 (Δχ2(18) = 75.944, p = .001, ΔCFI = .013), also ΔCFI exceeded .01, being close to reaching this level for comparison with M2 (Δχ2(9) = 47.524, p = .001, ΔCFI = .009) but not with M3 (Δχ2(9) = 37.561, p = .001, ΔCFI = .006). As AIC fit indices are consistent with the χ2 difference tests showing the lowest values for the reciprocal model (M4), we treat this model as the best fitting one.Footnote 1

In this reciprocal model presented in Fig. 1, the autocorrelations were .28 (T1–T2), .42 (T2–T3), and .31 (T1–T3) for positive orientation; .53 (T1–T2), .40 (T2–T3), and .29 (T1–T3) for work engagement; and .42, .47, and .49 for entrepreneurial success, respectively. As expected, positive orientation was positively related to the evaluation of entrepreneurial success over time. The relationships in both directions between T1 and T2 as well as between T1 and T3 exceeded the criterial p value. This indicates that T1 positive orientation is positively related to success in entrepreneurial activity at T2 and even, in the long run, at T3. The opposite is also true—the initial (T1) evaluation that one’s business is going well is related to higher positive orientation at T2 and T3; however, this is not the case between T2 and T3. Thus, the expectations concerning the reciprocal relationship between positive orientation and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success were generally supported. Positive orientation at T2 was also positively related to entrepreneurs’ work engagement at T3, but not between T1 and T2. The reverse relationships from work engagement to positive orientation were also statistically significant for T1–T2 and T2–T3 intervals, but not for the T1–T3 interval. This suggests that these reciprocal relationships operate in rather shorter time intervals. What is somewhat unexpected is that the reciprocal relationships between work engagement and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success were not supported. None of the relationships from work engagement to success were statistically significant, neither T1–T2, nor T2–T3 or T1–T3. As regards the opposite direction, only T1–T2 success–engagement relationship exceeded the criterial p value.

The final model (M4) of reciprocal relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and evaluation of entrepreneurial success. Note: +p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; standardized path coefficients are reported; solid lines = statistically significant paths; dotted lines = statistically non-significant paths; for simplicity of the figure the stability relationships are not presented, being however included in the model

To conclude, our results generally supported the reciprocal relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success over time. Many of the postulated paths in both directions between these variables were statistically significant; moreover, the reciprocal model was the best fitted to the data, better than the stability, causality, and reversed causation models. This supports our hypothesis.

3.4 Changes in the Levels of Variables

Finally, we applied the latent growth curve analysis (Arbuckle 2005; Little 2013) to test whether the level of each variable changed over time and to investigate interindividual variability in this change. For each of the study variables, the latent growth model had acceptable fit (Table 2). Significant variances in intercepts indicate that participants differed in the initial level of positive orientation, work engagement, and evaluation of entrepreneurial success. However, non-significant variances in slopes indicate that they did not differ in the rate of change in any of these variables. These results show that there were no significant changes in any of these variables over time, answering our research question.

4 Discussion

Based on the COR theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2011) and on the positive orientation theory (Caprara et al. 2009, 2012), we investigated the reciprocal relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success. We proposed that positive orientation could serve as a personal resource maintaining engagement in entrepreneurial activity and that this could lead entrepreneurs to feel successful in this activity. On the other hand, feeling successful in action may lead to a greater engagement and to building personal resources in the long run.

Our results show that entrepreneurs’ (business owners’) positive orientation is indeed dynamically related to their work engagement and evaluation of entrepreneurial success. Their positive orientation fosters engagement in entrepreneurial activity and experiencing the success of their firms, and vice versa; however, these relationships were not found to be statistically significant between all measurement times (see Fig. 1). Generally, when entrepreneurs evaluate the success of their businesses as high compared to other businesses in the same sector and region, with time they have higher level of positive orientation, what means that they are more likely to view themselves, life, and the future more positively. This may allow them to welcome new opportunities and cope with adversities (Caprara et al. 2009) and may lead to their personal flourishing—to the development of their personal resources and work engagement. Over time, entrepreneurs who strongly engage in work increase their positive orientation level, namely become more confident in themselves, develop more positive expectations concerning the future, and enjoy higher life satisfaction. The relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success are shown to be reciprocal and long-lasting, which confirms the postulates of the COR theory (Hobfoll 1989, 2011) and the beliefs-affect-engagement model (Laguna 2018).

The present study provides further empirical evidence that positive orientation is indeed a personal resource important in the work context (Caprara et al. 2018). Our results are congruent with the findings showing that positive orientation is positively related to the work engagement of paid employees and to their job performance (Alessandri et al. 2015a). We have found similar mechanisms in entrepreneurs, and the strength of these relationships is similar as in employees (for example .29–.31 for the relationship between positive orientation and employees’ in-role job performance; Alessandri et al. 2012). The results of this longitudinal study confirm also more general postulates of the beliefs-affect-engagement model (Laguna 2018), proposing that positive orientation, being accompanied by positive affect, fosters activity engagement and, consequently, performance.

Most of the previous studies on dynamic mechanisms such as gain spirals (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008; Hobfoll 1989) were carried out as two-wave studies (e.g., Llorens et al. 2007). To test such relationships fully, we performed a three-wave study with 7-month intervals, as at least three measurement times are necessary to uncover dynamic mechanisms (Lindsley et al. 1995). Such a time interval was chosen as long enough to observe changes in the performance of a firm, which are a matter of months rather than weeks (e.g., Gielnik et al. 2014; Schaufeli et al. 2012). Upward spirals resulting in a subsequent increase in the levels of variables were not detected. The levels of positive orientation, work engagement, and the evaluation of entrepreneurial success remained relatively stable over the entire time of 21 months. We ascribe this to self-correcting, deviation-counteracting cycles (Lindsley et al. 1995). Such cycles may occur in a short time interval when a decrease in variables is followed by their increase, or the other way around (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008; Hobfoll 1989), resulting in a relatively stable level in the long run. Our results confirm that reciprocal and cyclic relationships between variables are distinct mechanisms (Lindsley et al. 1995). The lack of upward spirals seems to protect entrepreneurs from overconfidence, which may tend to deprive their firms of resources (Hayward et al. 2006), and from overworking due to very high work engagement; this however await verification in future research.

A possible alternative explanation may be that the lack of increases in the levels of the variables should be attributed to their relatively high initial level, leaving no room for further increase (a ceiling effect). This can be ruled out, however, given the initial mean level of each variable (Table 1). On a scale from 1 to 5, mean scores range between 2.64 for evaluation of success and 3.83 for positive orientation. Though relatively high, they are not extremely high, leaving a potential of increase, especially in case of entrepreneurial success evaluation (mean scores around the middle point of the scale). Therefore, a ceiling effect is not likely to be responsible for the lack of upward spirals in our study.

4.1 Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

We applied a longitudinal field study design. However, even with this highly recommended design (Shepherd, 2015; Stephan, 2018), we cannot state the causal relationships between the variables with certainty. Experimental studies are welcome to test such relationships in controlled settings.

Furthermore, a different time frame of future studies may make it possible to test whether gain spirals occur in shorter, or perhaps longer, time intervals. As longitudinal studies on entrepreneurship are very demanding and therefore relatively rare (Shepherd, 2015), it is not easy to answer what time frame would be the best for investigating the dynamics of entrepreneurial success. The COR theory does not specify a time frame in which the maintenance of the baseline level of resources or changes in resource levels may occur, either. The investigation of resource gain cycles and spirals with different time intervals may allow researchers to detect time-specific relationships. Moreover, intensive longitudinal research distinguishing the stable and changeable components of each construct may make the picture of relationships between positive beliefs, engagement, and performance even more complex (Laguna, 2018).

Our measure of entrepreneurial success refers to a comparison with other businesses from the same sector and region. Such evaluation of success is broadly used in research on entrepreneurship (e.g., Baron 2007; Gielnik and Frese 2013; Wach et al. 2016), being successfully validated as business performance measure (Wiklund, 1999), and even preferred over objective ratings of business performance (Dijkhuizen et al. 2017). Being more unbiased than a direct evaluation of success (not based on a comparison with other firms), it is still a subjective evaluation which may be affected by specific response tendencies (Podsakoff et al. 2012). Therefore, in future studies, objective evidence of entrepreneurial success should be considered.

Our results are limited to small and medium-sized enterprises. They constitute more than 90% of European businesses and provide the majority of private employment (Muller et al. 2015). Further studies of micro-entrepreneurs as well as managers and owners of larger enterprises are welcome.

Another limitation is that our results come from one country and await replication. We would welcome replications for two reasons. First, entrepreneurial activity is always embedded in a specific cultural, social, and economic context, which may affect its outcomes (e.g., Moriano et al. 2012). Second, the level of positive beliefs differs across countries, and in Poland the level of negative self-evaluation has been observed to be higher than in other countries (e.g., U.S. or Italy; Alessandri et al. 2015b). This may suggest that the role of positive orientation may be different in other cultural contexts, and this idea awaits future research.

4.2 Implications for Practice

The results suggest that the accumulation of personal resources, such as positive orientation, may provide energy to engage in entrepreneurial activity and, in consequence, to succeed in business. This can be done through trainings aimed at increasing positive orientation and its components, namely self-assurance, optimism, and life satisfaction. Such trainings, however, should be addressed only to those who suffer from a low level of positive orientation and not to entrepreneurs who suffer from overconfidence (Hayward et al. 2006). To be able to distinguish between these two groups, a careful assessment of positive orientation and its components is necessary during the recruitment for trainings. The short measure of positive orientation used in this study may serve such screening purposes well (Caprara et al. 2012).

As opposite relationships—from success to work engagement and positive orientation—have also been confirmed, this suggests that (self-)appreciation of success, rewarding what has already been achieved may help to change these successes into motivational cues for future actions leading to personal resources gains (Gorgievski and Hobfoll 2008; Hobfoll 1989). As entrepreneurs tend to be future-oriented (Przepiorka 2016), such appreciation of successes achieved and celebration of what has already been done may not be easy for them. Therefore, this needs to be planned in advance. As it happens in big corporations, also in smaller enterprises some special events may assure an entrepreneur and their team that their resources and energy dedicated to work have brought good effects. It seems that this may strengthen the links between feeling successful, engagement, and personal resources, which may foster future successes and protect the business from failure.

Notes

In an additional analysis we controlled for the potential effects of capital availability. Access to financial capital can influence business performance, since it serves as a buffer against unforeseen troubles which can arise from changing environmental conditions (Wiklund, 1999). Therefore, we controlled for this factor in our model. Taking into account that it is difficult to obtain an objective measure of access to capital, we used the recommended subjective measure of capital availability satisfaction (Wiklund, 1999). In addition to the single item used by Wiklund (1999) that refers to capital available for business development, we used two items referring to the sufficiency of capital available for regular investments and to keep pace with competitors (e.g., “Do you have sufficient capital for regular investments?”). Therefore, our measure consisted of three items answered on a 7-point scale (1 = insufficient, 7 = fully satisfactory). We confirmed that this measure captured a single dimension at each measurement time: T1 (χ2(1) = .502, p = .479, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = .001), T2 (χ2(1) = 19.027, p < .001, CFI = .958, RMSEA = .032), and T3 (χ2(1) = 8.849, p = .003, CFI = .974, RMSEA = .028); Cronbach’s α was .91, .93, and .95 respectively. Based on these results, we included capital availability in the model as an observable score. This variable was added to the reciprocal model (M4) to test whether it affects entrepreneurial success. The model including capital availability fitted the data significantly worse than the reciprocal model M4 (χ2(864) = 1483.145, p < .001, RMSEA = .059, CFI = .870, AIC = 1915.145; comparison with M4: Δχ2(123) = 301.257, p < .001, ΔCFI = .030, higher AIC value), though it showed statistically significant effects of capital availability on entrepreneurial success at each measurement time (.51 at T1, .44 at T2, and .46 at T3, all significant at p < .001). As this analysis shows that the reciprocal model (M4) fits the data better than it does after controlling for capital availability, we treat this model as the final one.

References

Alessandri, G., Borgogni, L., Schaufeli, W. B., Caprara, G. V., & Consiglio, C. (2015a). From positive orientation to job performance: The role of work engagement and self-efficacy beliefs. Journal of Happiness Studies,16(3), 767–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9533-4.

Alessandri, G., Vecchione, M., Eisenberg, N., & Łaguna, M. (2015b). On the factor structure of the Rosenberg (1965) General Self-Esteem Scale. Psychological Assessment,27(2), 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000073.

Alessandri, G., Vecchione, M., Tisak, J., Deiana, G., Caria, S., & Caprara, G. V. (2012). The utility of positive orientation in predicting job performance and organisational citizenship behaviors. Applied Psychology,61(4), 669–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00511.x.

Arbuckle, J. (2005). Amos 6.0 User’s Guide. Spring House: Amos Development Corporation.

Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., Fletcher, L., Robinson, D., Holmes, J., et al. (2015). Engagement and performance. Perth: National Institute for Health Research.

Baron, R. A. (2007). Entrepreneurship: A process perspective. The psychology of entrepreneurship (pp. 19–40). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.

Baron, R. A., Hmieleski, K. M., & Henry, R. A. (2012). Entrepreneurs’ dispositional positive affect: The potential benefits—and potential costs—of being “up”. Journal of Business Venturing,27(3), 310–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.002.

Baum, J., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology,89(4), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.587.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research,21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005.

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., & Caprara, M. (2018). Associations of positive orientation with health and psychosocial adaptation: A review of findings and perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12325.

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., Eisenberg, N., Kupfer, A., Steca, P., Caprara, M. G., et al. (2012). The positivity scale. Psychological Assessment,24(3), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026681.

Caprara, G. V., Fagnani, C., Alessandri, G., Steca, P., Gigantesco, A., Sforza, L. L. C., et al. (2009). Human optimal functioning: The genetics of positive orientation towards self, life, and the future. Behavior Genetics,39(3), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-009-9267-y.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling,9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Chirkowska-Smolak, T. (2012). Psychologiczny model zaangażowania w pracę. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

Cohen, J. (1994). The earth is round (p < .05). American Psychologist,49(12), 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.49.12.997.

Daniels, K., Brough, P., Guppy, A., Peters-Bean, K. M., & Weatherstone, L. (1997). A note on a modification to Warr’s measures of affective well-being at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,70(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00638.x.

Dijkhuizen, J., Gorgievski, M. J., van Veldhoven, M. J. P. M., & Schalk, R. (2016). Feeling successful as an entrepreneur: A job demands—resources approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal,12(2), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0354-z.

Dijkhuizen, J., Gorgievski, M., van Veldhoven, M., & Schalk, R. (2017). Well-being, personal success and business performance among entrepreneurs: A two-wave study. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9914-6.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology,47, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2.

Gielnik, M., Barabas, S., Frese, M., Namatovu-Dawa, R., Scholz, F. A., Metzger, J. R., et al. (2014). A temporal analysis of how entrepreneurial goal intentions, positive fantasies, and action planning affect starting a new venture and when the effects wear off. Journal of Business Venturing,29(6), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.09.002.

Gielnik, M., & Frese, M. (2013). Entrepreneurship and poverty reduction: Applying I-O psychology to microbusiness and entrepreneurship in developing countries. In J. Olson Buchanan, L. Koppes Bryan, & L. Foster Thimpson (Eds.), Using I-O psychology for the greater good: Helping those who help others (pp. 394–438). New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis.

Gorgievski, M. J., Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). Expanding the boundaries of psychological resource theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,84(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02015.x.

Gorgievski, M. J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2008). Work can burn us out or fire us up: Conservation of resources in burnout and engagement. In J. R. B. Halbesleben (Ed.), Handbook of stress and burnout in health care (pp. 7–22). Hauppauge NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Gorgievski, M. J., Moriano, J. A., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Relating work engagement and workaholism to entrepreneurial performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology,29(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2012-0169.

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress,22(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432.

Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). New York: Psychology Press.

Hayward, M. L. A., Shepherd, D. A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science,52(2), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0483.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist,44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology,6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology,84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling,6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Laguna, M. (2018). Towards explaining the “how” of positive orientation: The beliefs-affect-engagement model. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12336.

Laguna, M., Alessandri, G., & Caprara, G. V. (2016). Personal goal realisation in entrepreneurs: A multilevel analysis of the role of affect and positive orientation. Applied Psychology,65(3), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12061.

Łaguna, M., Oleś, P. K., & Filipiuk, D. (2011). Orientacja pozytywna i jej pomiar: Polska adaptacja Skali Orientacji Pozytywnej. Studia Psychologiczne,49, 47–54.

Laguna, M., Razmus, W., & Żaliński, A. (2017). Dynamic relationships between personal resources and work engagement in entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,90(2), 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12170.

Lindsley, D. H., Brass, D. J., & Thomas, J. B. (1995). Efficacy-performance spirals: A multilevel perspective. The Academy of Management Review,20(3), 645–678. https://doi.org/10.2307/258790.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Llorens, S., Schaufeli, W., Bakker, A., & Salanova, M. (2007). Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist? Computers in Human Behavior,23(1), 825–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.11.012.

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., & Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior,27(3), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.373.

Meredith, W. (1993). Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika,58(4), 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294825.

Moriano, J. A., Gorgievski, M. J., Laguna, M., Stephan, U., & Zarafshani, K. (2012). A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Career Development,39(2), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845310384481.

Muller, P., Caliandro, C., Peycheva, V., Gagliardi, D., Marzocchi, C., Ramlogan, R., et al. (2015). Annual report on European SMEs 2014/2015. Luxembourg: European Commission.

Oleś, P. K., Alessandri, G., Oleś, M., Bak, W., Jankowski, T., Laguna, M., et al. (2013). Positive orientation and generalized self-efficacy. Studia Psychologica,1(55), 47–59.

Pitts, S. C., West, S. G., & Tein, J.-Y. (1996). Longitudinal measurement models in evaluation research: Examining stability and change. Evaluation and Program Planning,19(4), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(96)00027-4.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology,63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

Przepiorka, A. (2016). What makes successful entrepreneurs different in temporal and goal-commitment dimensions? Time & Society,25(1), 40–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X15577264.

Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,16(4), 353–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701595438.

Razmus, W., & Laguna, M. (2018). Dimensions of entrepreneurial success: A multilevel study on stakeholders of micro-enterprises. Frontiers in Psychology,9, 791. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00791.

Schaufeli, W. B. (2013). What is engagement? In C. Truss, K. Alfes, R. Delbridge, A. Shantz, & E. Soane (Eds.), Employee engagement in theory and practice (pp. 15–35). London: Routledge.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. (2004). Utrecht work engagement scale. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Schaufeli, W. B., Ouweneel, E., & Le Blanc, P. M. (2012). Don’t leave your heart at home: Gain cycles of positive emotions, resources, and engagement at work. Career Development International,17(6), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431211280123.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies,3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326.

Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Party On! A call for entrepreneurship research that is more interactive, activity based, cognitively hot, compassionate, and prosocial. Journal of Business Venturing,30(4), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.02.001.

Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives,32(3), 290–322. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0001.

Sturman, M. C. (2007). The past, present, and future of dynamic performance research. In J. J. Martocchio (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 26, pp. 49–110). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/121.

Tarnawa, A., & Zadura-Lichota, P. (Eds.). (2013). Raport o stanie sektora małych i średnich przedsiębiorstw w Polsce w latach 2011–2012. Warszawa: Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości.

van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics,29(4), 351–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9074-x.

Wach, D., Stephan, U., & Gorgievski, M. (2016). More than money: Developing an integrative multi-factorial measure of entrepreneurial success. International Small Business Journal,34(8), 1098–1121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615608469.

Wiklund, J. (1999). The sustainability of the entrepreneural orientation-performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,24(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902400103.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009a). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior,74(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.003.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009b). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,82(1), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X285633.

Acknowledgements

This study draws on parts of a large longitudinal dataset that was also partially used in Laguna, M., Razmus, W., Żaliński, A. (2017). Dynamic relationships between personal resources and work engagement in entrepreneurs, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 248–269. The present study focusses on the effects of positive orientation and explores mechanisms related to business success, all of which were not considered in Laguna et al. (2017).

Funding

This research was financed by the National Science Centre, Poland, Grant No. DEC-2013/10/M/HS6/00475.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data Availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Laguna, M., Razmus, W. When I Feel My Business Succeeds, I Flourish: Reciprocal Relationships Between Positive Orientation, Work Engagement, and Entrepreneurial Success. J Happiness Stud 20, 2711–2731 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0065-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0065-1