Abstract

This study examines possible positive spillovers and negative consumption externalities of the average income in a geographic area (locality income) on individuals’ life satisfaction, focusing on two issues. The first is whether the effect of locality income on life satisfaction is sensitive to the scale of geographic units. The second is how the choice of control variables affects the estimated effect of locality income. The analysis of 142,780 survey respondents nested within 31,000 neighbourhoods, 5,000 local communities and 430 municipalities suggests that the positive spillovers of locality income are stronger in immediate neighbourhoods and local communities than at the municipality level. The positive association between locality income and life satisfaction to a large extent is attributable to the selective geographic concentration of individuals by income, marital status, and homeownership. Although the results do not rule out the existence of negative consumption externalities, its effect, if any, does not offset the positive spillovers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A region in the Luttmer’s study is defined as a Public Use Microdata area (PUMA), with an average population of 150,000). PUMAs are used by the US Census Bureau to partition a state into sub-state areas for statistical reporting purpose. A PUMA is generally the aggregate of small counties or the aggregate of census tracts in large metropolitan areas, with at least 100,000 people.

Barrington-Leigh and Helliwell (2008) also address this issue. However, their study is based on a much smaller sample. For instance, only about 9,000 respondents in their study are nesting simultaneously in neighbourhoods, local communities, and municipalities, while the sample size in the current study is 15 times larger. More importantly, the present study differs from theirs in modelling approaches, particularly in terms of the sequence of entering control variables.

In analysis with both individual-level and group-level variables, the estimation of the effects of group-level variables is equivalent to a grouped data model. That is, the group means of the individual-level outcome variables, after adjusting for group differences in individual level control variables, is regressed on the group-level variables. The reliability of grouped data analysis strongly depends on the average size of observations within each group and the number of groups (Devereux 2007; Raudenbush et al. 2000).

A CMA or CA contains one or more adjacent municipalities situated around a major urban core. A census metropolitan area must have a total population of at least 100,000 of which 50,000 or more live in the urban core. A census agglomeration must have an urban core population of at least 10,000.

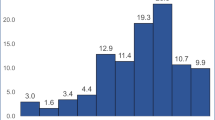

The distribution of the sample across surveys is the following: 12,581 cases from the 2008 GSS, 12,214 cases from 2009 GSS, 9,777 from the 2010 GSS, 14,308 from the 2011 GSS, 30,609 from the 2009 CCHS, 31,573 from the 2010 CCHS, and 31,718 from the 2011 CCHS. Put together, there are about 5 respondents per neighbourhood, 29 respondents per local community, and 332 respondents per municipality.

This is computed by dividing the after-tax income by a scale that assigns a decreasing value to the second and subsequent family members. In the census microdata file, the scale is the sum of the following values: 1.0 is assigned to the oldest person in the family, 0.4 is assigned to each of the other family members aged 16 and over, and 0.3 to each of family members under age 16. For persons not in families, the value is set to 1.0. Empirically, this scale is close to the square root of the family size.

The next higher geographic level is province, which is too broad. For instance, North Bay CMA in northern Ontario is drastically different from Toronto CMA in southern Ontario in terms of population size, economic scales, population diversity, and climate.

Log odds ratios or odds ratios from logit or probit regression are affected by unobserved heterogeneity that may be reduced when an additional variable is added to the model even though the added variable is unrelated to the independent variables already in the model.

OLS with clustering correction and 2-level HLM produce similar standard errors for group-level predictors, but the former tends to produce larger standard errors for individual-level predictors than the latter. These results suggest that for the data and model specifications used in the present study, OLS with clustering correction yields more conservative standard errors than the HLM approach.

In the GSS, the average weight ranges from 1,500 to 2,000 depending on the survey year. In the CCHS, the average weight is about 640. Standardizing these weights avoids an overestimation of the critical level while maintaining the same distributions as those of non-standardized weights. Alternatively, the weights can be standardized so the sum of the standardized weights is the same in each survey year/type and equals to the sample size of the smallest survey year/type. Additional analysis (not shown) suggests that there is no substantive difference in model estimates by using either weighting method.

Out of the 31,024 neighbourhoods in the data, 3,301 contain at least 10 respondents. Thus each quintile has about 660 neighbourhoods.

This decomposition is based on two equations: 1: (B − B′)/B = (β − β′)/β, and 2: β − β′ = Σβj′ *ρ XZj where B and β are the regression coefficient and standardized coefficient of neighbourhood income in Model 1, and B′ and β′ are the regression coefficient and standardized coefficient of neighbourhood income in Model 2. βj′ are the standardized coefficients of all other control variables in Model 2, and ρ XZj are the Pearson correlation between neighbourhood income and each of the control variables. The contribution of each control variable to the change in the coefficient of neighbourhood income from Model 1 to Model 2 is βj′*ρ XZj /Σ(βj′*ρ XZj ). Detail proof and empirical examples of this decomposition method can be obtained from the author.

In the data, neighbourhood income is strongly correlated with community income (Pearson r = 0.81).

In these models, community average income is calculated by excluding a respondent’s immediate neighbourhood, and municipality average income is calculated by excluding a respondent’s local community. This procedure is to reduce correlation between locality incomes at various geographic levels. The nested models with three levels of locality income are not affected by multicollinearity. In all models, no coefficient has a variance inflation factor (VIF) value over 2.5. A general rule is that a VIF value of 10 or higher indicates considerable collinearity.

In a model similar to Model 3 in Table 5 but using self-reported health as the outcome, the coefficient is 0.16 for neighbourhood income, 0.11 for community income, and both are significant at p < 0.001. The coefficient for municipality income is not significant.

Luttmer did control for the size of metropolitan area population and fraction of blacks in PUMA. He also performed an additional test to control for PUMA housing price. These controls, however, may not fully capture other PUMA attributes that may be negatively associated with happiness. In the data used in the present study, the negative coefficient of municipality income in Model 2 hardly changes when only controlling for other areal attributes, it changes to positive and significant only when the fixed effects of CMAs/CAs are controlled for.

While the causal direction between self-reported health and life satisfaction is in doubt, it is reasonable to assume that chronic physical and mental illnesses can affect people’s evaluation of their current SWB. Veenhoven (2008) suggests that happiness protects one against falling ill, but it does not cure diseases. Chronic physical and mental illnesses include asthma, arthritis, back problems, high blood pressure, migraine, chronic bronchitis, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stomach or intestinal ulcers, effects of a stroke, urinary incontinence, bowel disorder, Alzheimer's disease or other dementia, mood disorder (such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia), and anxiety disorder (such as a phobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder or a panic disorder). The mastery scale measures the extent to which people believe that their life-chances are under their control.

Model results are available on request. The 2008 GSS contains only 12,580 respondents nested within 9,538 neighbourhoods, 4,119 communities, and 378 municipalities. Likely because of the small sample and the corresponding larger coverage errors and measurement errors, none of the coefficients of community income in model 1 to model 3a are statistically significant, although the size of the coefficients are similar to those reported in Table 5.

References

Abel, A. (2005). Optimal taxation when consumers have endogenous benchmark levels of consumption. The Review of Economic Studies, 72(1), 21–42.

Angrist, J., & Pischke, J. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Arceneaux, K., & Nickerson, D. W. (2009). Modeling certainty with clustered data: A comparison of methods. Political Analysis, 17, 177–190.

Barrington-Leigh, C., & Helliwell, J. (2008). Empathy and emulation: Life satisfaction and the urban geography of comparison groups. NBER Working Paper, No. 14593.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2009). International evidence on well-being. In A. B. Krueger (Ed.), National time accounting and subjective well-being (pp. 155–226). Chicago: NBER and University of Chicago Press.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1733–1749.

Bonikowska, A., Helliwell, J., Hou, F., & Schellenberg, G. (2013). An assessment of life satisfaction responses on recent Statistics Canada surveys. Analytical studies branch research paper series. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Borgonovi, F. (2008). Doing well by doing good—the relationship between formal volunteering and self-reported health and happiness. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 2321–2334.

Brereton, F., Clinch, P., & Ferreira, S. (2008). Happiness, geography and the environment. Ecological Economics, 65, 386–396.

Clark, A., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Devereux, P. J. (2007). Small-sample bias in synthetic cohort models of labor supply. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22, 839–848.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 809–827.

Diener, E., & Chan, M. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-being, 3(1), 1–43.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicator Research, 112, 497–527.

Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27, 35–47.

Easterlin, R. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11176–11183.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness. The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Fowler, J., & Christakis, N. (2008). Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart study. British Medical Journal, 337, a2338, 1–9.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. Economic Journal, 110, 918–938.

Frijters, P., & Beatton, T. (2012). The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 82, 525–542.

Helliwell, J. (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling, 20, 331–360.

Helliwell, J., & Huang, H. (2010). How’s the job? Well-being and social capital in the workplace. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 63(2), 205–227.

Hou, F., & Myles, J. (2005). Neighbourhood inequality, neighbourhood affluence and population health. Social Science and Medicine, 60, 1557–1569.

Kingdon, G. G., & Knight, J. (2007). Community, comparisons and subjective well-being in a divided society. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 64, 69–90.

Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review, 20, 635–649.

Layard, R. (2006). Happiness and public policy: A challenge to the profession. The Economic Journal, 116, C24–C33.

Luttmer, E. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 963–1002.

Macintyre, S., Ellaway, A., & Cummins, S. (2002). Place effects on health: How can we conceptualise, operationalise, and measure them? Social Science and Medicine, 55, 125–139.

Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

Morrison, P. (2011). Local expressions of subjective well-being: The New Zealand experience. Regional Studies, 45(8), 1039–1058.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2010). Income inequality, perceived happiness, and self-rated health: Evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 1358–1366.

Primo, D. M., Jacobsmeier, M. L., & Milyo, J. (2007). Estimating the impact of state policies and institutions with mixed-level data. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 7(4), 446–459.

Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., Cheong, Y. F., & Congdon, R. T. (2000). HLM5 hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.

Schenker, N., & Raghunathan, T. (2007). Combining Information from multiple surveys to enhance estimation of measures of health. Statistics in Medicine, 26, 1802–1811.

Shields, M., Price, S. W., & Wooden, M. (2009). Life satisfaction and the economic and social characteristics of neighbourhoods. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 421–443.

Siahpush, M., Spittal, M., & Singh, G. K. (2008). Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. American Journal of Health Promotion, 23(1), 18–26.

Stafford, M., & Marmot, M. (2003). Neighborhood deprivation and health: Does it affect us all equally? International Journal of Epidemiology, 32, 357–366.

Subramanian, S. V., Kim, D., & Kawachi, I. (2005). Covariation in the socioeconomic determinants of self rated health and happiness: A multivariate multilevel analysis of individuals and communities in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 664–669.

van Praag, B., & Baarsma, B. (2005). Using happiness surveys to value intangibles: The case of airport noise. Economic Journal, 115, 224–246.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 1–39.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 449–469.

Welsch, H. (2006). Environment and happiness: Valuation of air pollution using life satisfaction data. Ecological Economics, 58, 801–813.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the journal editor and reviewers for their constructive suggests. The author is grateful to Aneta Bonikowska, Kristyn Frank, Haifang Huang, Grant Schellenberg, and Christopher Schimmele for advice and comments on various issues related to estimation strategies and interpretation of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, F. Keep Up with the Joneses or Keep on as Their Neighbours: Life Satisfaction and Income in Canadian Urban Neighbourhoods. J Happiness Stud 15, 1085–1107 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9465-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9465-4