Abstract

Adherence to masking recommendations and requirements continues to have a wide variety of impacts in terms of viral spread during the ongoing pandemic. As governments, schools, and private sector businesses formulate decisions around mask requirements, it is important to observe real-life adherence to policies and discern subsequent implications. The CDC MASCUP! observational study tracked mask-wearing habits of students on higher-education campuses across the country to collect stratified data about mask typologies, correct mask usage, and differences in behaviors at locations on a college campus and in the surrounding community. Our findings from a single institution include a significant adherence difference between on-campus (86%) and off-campus sites (72%) across the course of this study as well as a notable change in adherence at the on-campus sites with the expiration of a county-wide governmental mandate, despite continuance of a university-wide mandate. This study, completed on and around the campus of East Tennessee State University in Washington County TN, was able to pivotally extract information regarding increased adherence on campus versus the surrounding community. Changes were also seen when mask mandates were implemented and when they expired.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic there was uncertainty among both the public and the scientific community on curbing community transmission rates. Mask-wearing is a disease prevention tool that has been deployed in many previous outbreaks [1]. Recommendations and mandates for universal mask wearing as infection prevention emerged early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout the pandemic, it has remained a leading mitigation method. Masks are effective against transmission as COVID-19 is a virus that is primarily spread through water droplets from the mouth that are expelled during coughing, sneezing, or speaking. Masks work by blocking a considerable amount of these water droplets from escaping into the air, minimizing the possibility of another individual coming in contact with potentially infectious bodily fluids. A variety of masks have been used throughout the pandemic to help mitigate infection rates, including but not limited to cloth masks, surgical masks, respirators, as well as N95 or KN95 masks [1]. Through the course of the pandemic, studies have investigated the efficacy of wearing a mask to reduce viral transmission rates, yielding controversial results [2]. Additionally, perceptions of mask efficacy, the cultural acceptance of mask wearing, and local policies seem to be regionally and locally different across the United States [3]. Across most states in the US, mask wearing mandates were initially issued to reduce infection rates and enforce existing public health recommendations [4].

Between February and April of 2021 our team worked with members of the United States Public Health Service and set out to investigate the utilization of masking and the different types of masks worn in and around East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, TN, as part of the National Centers for Disease Control MASCUP! Study. The project goals for the study were two-fold. From a professional development standpoint, the project offered the opportunity to train a student team in community data science, study design and implementation, data collection and publication, and CDC passive observation techniques. The observational study goal was to compare differences in mask wearing adherence on campus vs. in the surrounding community. Additionally, a natural experiment was available when the mask mandate for Washington County, TN, was lifted during the study observation period.

Methods

Eight graduate-level public health students were selected and trained in passive observation skills through a specialized CDC protocol. They then conducted the observational study at five on-campus sites and five off-campus sites. Each student selected a location where study staff had been given permission to observe individuals. Observations took place on weekdays from February 8, 2021, to April 30, 2021. When the observations began, mask mandates were in place both on-campus and in Washington County, TN. On February 20, 2021, the county-wide mask mandate in Washington County, TN, was lifted, but the campus mask mandate remained in effect. Student study staff made observations for one-hour time periods and entered data using a standardized, campus-specific, IRB-approved REDCap form. The students completed observations at the same sites each week for the duration of the study. The team chose to record data for every third individual who entered the designated site. The information recorded included the date, location, time, and point such as entrance or exit of observation. For each observation, data was recorded on whether an individual (1) wore a mask, (2) did not wear a mask, or (3) if it was unknown whether they wore a mask. If the individual was reported as wearing a mask, students were asked to specify whether the mask was worn correctly or incorrectly and then to specify the type of mask: surgical mask, N95, cloth mask, neck gaiter, or other. Lastly, total time was recorded at the end of each observation period.

At the end of the REDCap data collection form was a section for explaining why individuals may have worn their masks incorrectly. Students were asked to report the most common errors in incorrect mask usage: (1) nose out, (2) mouth out, (3) only on the chin, (4) hanging from an ear, or (5) hanging from the neck. Then, if there was any circumstance that may have caused incorrect mask usage, that was reported as well such as eating/drinking, exercise/playing a sport, outdoors and not within six feet of others, or none. Lastly, there was an optional free response portion for observers to report any additional notations. Each week, a new REDCap form was completed and submitted for each team member for their observed location.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were calculated for masking behavior questions combined across all locations for the two time periods of interest (during and post the county-wide mask mandate in effect). The responses on mask wearing behaviors were compared between time periods via generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) to account for any clustering effect of repeated observations within a specific location. Comparisons were then made separately for the campus-only and non-campus locations between time periods (during and post county-wide mandate) via GLMMs, when the campus mask mandate remained in place. Finally, regardless of whether a mandate was in place, on-campus masking behaviors were compared to off-campus masking behaviors via GLMMs. Significance for all models was determined a priori at the α = 0.05 level.

Results

In total, the student research team observed N = 3262 individuals over the course of the study, with two observations being excluded due to an unknown status for mask wearing. The time period from the start of observations until the county-wide mask repeal included n = 587 observations, with the time period after the mask mandate was lifted including n = 2673 observations. Observations took place in both Johnson City (5 locations) and on the main campus (6 locations) of East Tennessee State University (ETSU).

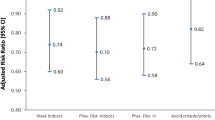

There was no significant difference between mask wearing when the mask mandate was in place compared to when it was not in place (86% vs. 82%, p = 0.06). Of most of those who wore a mask, there were no differences in wearing it properly between time periods both with and without a mandate (92% vs. 93%, p = 0.19). Mask types were similar between time periods, with cloth masks being the most common (70%), followed by surgical masks (25%), and the neck gaiters (4%). Very few people wore N95 (1%) or another kind of mask (< 1%). Overall mask wearing was common across the study ranging from 61 to 100% (Fig. 1). Having a county-wide mandate effect in place vs. removing the mandate did not indicate differences in mask wearing during this short time frame during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, when only looking at campus locations, having the mandate lifted did slightly reduce the number of mask-wearing individuals on campus, though this was not true for off-campus locations. Regardless of having a mandate in place, mask adherence at on-campus sites were consistently higher than those of the surrounding community locations.

When comparing the time periods within the campus locations (n = 1404), there was a statistically significant difference between the mask wearing during the mandate and post-mandate (95% vs 92%, p = 0.01). The odds of wearing a mask on campus were 2.14 (95% CI 1.20–3.83) times higher when the mask mandate was in effect compared to after it had been lifted. For those that were wearing a mask on campus (n = 1294), there was no difference in time periods for whether it was worn properly, with 94% of those wearing a mask in both time periods wearing it correctly (p = 0.74). At non-campus locations (n = 1856), there was no difference in wearing a mask during the mandate compared to after (77% vs. 75%, p = 0.51); however, there was a statistically significant difference for wearing it correctly (p = 0.04). Of those observed wearing a mask at an off-campus location (n = 1398), 88% wore it correctly during the mandate compared to 83% after the mandate was lifted.

When examining on-campus and off-campus mask wearing, regardless of time period, individuals observed at on-campus sites were more likely to wear masks than at off-campus observations (92% vs 75, p = 0.047). The odds of wearing a mask was 4.26 times higher (95% CI 1.02–17.78) while on campus compared to off campus (Fig. 2). Most of the on-campus locations had at least 85% mask wearing observed across all observation days, with the exception of one outdoor location (fountain). All off-campus locations had < 85% mask wearing observed across all observation days, with the lowest reported rate at an off-campus coffee shop (57%).

Discussion

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, local, regional, and national governments have grappled with concerns over the effectiveness and adherence to mask mandates among different populations [5]. Many officials have also called into question differences between mask types as to the effectiveness and safety of variances among common masks. Likewise, correct usage of a mask is an important distinguishing factor when evaluating the overall effectiveness of such mandates. This observational study, part of the CDC MASCUP! study [6], addresses a critical need for more empirical evidence on how mask wearing changes with mandates versus without them. This evidence may be even more crucial considering that governments are increasingly taking a more hands-off approach to these types of mandates, deferring instead to individual institutions, such as schools and private businesses to make such decisions.

Taking place between February and April 2021, this observational study sought to investigate the utilization and intricacies of masking behaviors in a community environment (Washington County, Tennessee) compared to a campus setting that had varying masking restrictions at the county and university levels. This study also encompassed a critical timeframe before and after expiration of the mask mandate in Washington County and how a county mandate impacted masking behaviors in a variety of locations.

Limitations of this study include the inequity between the number of observations occurring pre- and post-mandate, with post-mandate observations encompassing the majority of total. Another limitation lies in the accuracy of the true adherence rates depending on observation location. Individuals may deem it necessary to wear a mask in more crowded areas as opposed to a low-traffic campus setting or in indoor vs. outdoor locations or in locations where food is served (i.e., coffee shops).

Conclusion

The findings suggest several implications for both governmental bodies and university decision-makers. One is that institutional mandates are effective in providing significant adherence differences regardless of the presence of surrounding governance mandates. Despite the high rates of mask adherence, it is also true that campus adherence rates saw a decline after the expiration of the county-wide mandate, implying that while both county and institutional mandates are important, more localized ones may be more effective. The ability to wear a mask correctly, however, is not correlated with mask mandates and may instead be tied to education or willingness.

Further research could include tying observational mask data to concrete COVID-19 rates at the community or university levels. It may also be prudent to look at multiple time periods to see pre-mandate, during mandate, and post-mandate adherence rates, as these may offer significant differences from the two time periods observed in this study. Controlling for demographic differences such as race, sex, age, education level, and even political affiliation may also yield important results that distinguish the true impact of university mandates on masking behaviors across demographic groups.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Use masks to slow the spread of covid-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/masks.html. Accessed April 1, 2022

Li, H., Yuan, K., Sun, Y. K., Zheng, Y. B., Xu, Y. Y., Su, S. Z., Zhang, Y. X., Zhong, Y., Wang, Y. J., Tian, S. S., Gong, Y. M., Fan, T. T., Lin, X., Gobat, N., Wong, S. Y. S., Chan, E. Y. Y., Yan, W., Sun, S. W., Ran, M. S., Bao, Y. P., Shi, J., & Lu, L. (2022). Efficacy and practice of facemask use in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35105851/. Accessed April 1, 2022

Kemmelmeier, M., & Jami, W. A. (2021). Mask wearing as cultural behavior: An investigation across 45 U.S. states during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648692

Covid-19 updates. COVID-19 Updates | Washington County, TN. https://www.washingtoncountytn.org/284/COVID-19-Updates. Accessed April 1, 2022

Yoon, J., Allen, J., & Burr A. (2021). When it comes to their own pandemic precautions, state legislatures in the U.S. are all over the map. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/08/us/mask-mandate-state-legislature-coronavirus.html. Published February 8, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022

Mask adherence surveillance at colleges and Universities Project (MASCUP!). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/whatis/healthequityinaction/topics/mascup.html. Published September 16, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Margaret Riggs, PhD, MPH, MS and Michaila Czarnik, MPH for their contributions to the MASCUP! project, allowing us to conduct this research. Furthermore, we would like to thank the Centers for Disease Control for allowing us to take part in this study.

Funding

CDC Supported MASCUP! Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authorship and research assistance; data entry; data tabulation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Condra, A., Coston, T., Jain, M. et al. Mask Adherence to Mask Mandate: College Campus Versus the Surrounding Community. J Community Health 48, 496–500 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01187-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01187-8