Abstract

This paper exploits the unexpected decline in the death rate from cardiovascular diseases since the 1970s as a large positive health shock that affected predominantly old-age mortality; i.e. the fourth stage of the epidemiological transition. Using a difference-in-differences estimation strategy, we find that US states with higher mortality rates from cardiovascular disease prior to the 1970s experienced greater increases in adult life expectancy and higher education enrollment. Our estimates suggest that a one-standard deviation higher treatment intensity is associated with an increase in adult life expectancy of 0.37 years and 0.07–0.15 more years of higher education.

Data source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

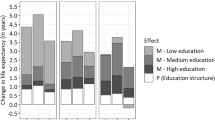

Source: columns 3 and 6 in Table 4

Source: column 3 in Table 4

Source: column 6 in Table 4

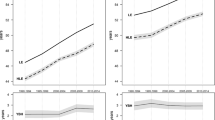

Source: column 6 in Table 5

Source: column 3 in Table 5

Source: column 6 in Table 5

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, for white U.S. American men, the incidence of heart attack or fatal coronary heart disease is about 4% in the 55–64 age bracket and almost 8 and 12% in the 65–74 and 75–84 age brackets, respectively; see Mozaffarian et al. (2015).

In biology, aging is understood as the “intrinsic, cumulative, progressive, and deleterious loss of function that eventually culminates in death” (Arking 2006). For an introduction to the evolutionary foundations of human aging, see Kirkwood (1999). For a detailed formal description of the aging process by reliability theory, see Gavrilov and Gavrilova (1991).

For all variables derived from IPUMS, we apply the personal weight (PERWT) to ensure representativeness.

Data on College Enrollment II in 1960 are missing for the following states: Delaware, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming. In the baseline, we interpolate missing values, however, similar results are obtained if these are kept as missing observations.

The color-groups correspond to quantiles of the distribution of CVD mortality in 1960, such that each color contains 12 states. Appendix Figure 2 in the online appendix shows a map of the same variable, but where states have been grouped into nine equally sized intervals of CVD.

We obtain similar results if Initial Income is derived for the age group 30–65.

Throughout the analysis, the regressions include state and year fixed effects and are weighted by the size of white population in 1960.

The estimated coefficients of these control variable interactions are not reported in the tables to save space. The estimates for Initial Mortality show, for example, that life expectancy at age 30 was increasing more from 1940 to 1950 for states with higher Initial Mortality, whereas from 1950 onwards, there are no trend differences. These estimates are available upon request.

Appendix Figures 5 and 6 graph partial correlation plots without the baseline controls, which then corresponds to the specifications in column(1) and (4) of Table 4.

Redefining the continuous measure of treatment into an indicatorwhich equals one/zero if states have a CVD-mortality rate higher/lower than the sample median suggests that high-CVD states experienced 0.53 years increase in life expectancy at age 30 relative to low-CVD states in 2000 relative to 1960 (see Appendix Table 9 in the online appendix).

Data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute indicate that the cardiovascular disease mortality rate decreased by about 50% from 1960–2000.

If we do not condition on state fixed effects, we find that average adult life expectancy of the treatment states are converging towards the control states after 1960.

Appendix Figure 4 in the online appendix depicts the state-demeaned development of average College Enrollment II from 1940 to 2000, where states have been grouped according to whether their treatment value is below or above the sample median (as we also did for adult life expectancy). In line with the estimates in Table 5, pretreatment trends are similar between the two groups, while only after the 1960s does the treatment group catch up and overtake the control group in terms of the average enrollment rate. In addition, Appendix Figures 7 and 8 graph partial correlation plots without the baseline controls, which then corresponds to the specifications in column (1) and (4) of Table 5.

We show in the Online Appendix that the results for adult life expectancy and higher education enrollment are robust to the inclusion of state-specific linear time trends.

We only report robustness checks for the variables where we have established a significant effect of the cardiovascular revolution in the baseline specification.

We do so in practice by interacting these cross-sectional state characteristics with a full set of year fixed effects.

This also partially addresses the issue of population sorting caused by the shock we are considering. In particular, in an unreported specification, we show that CVD is actually able to explain time variation in migration rates, however, this effect completely disappears once we control for Initial Migration interacted with a full set of year fixed effects.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2006). Disease and development: The effect of life expectancy on economic growth. NBER working paper 12269.

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2007). Disease and development: The effect of life expectancy on economic growth. Journal of Political Economy, 115, 925–985.

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2014). Disease and development: A reply to bloom: Canning, and fink. Journal of Political Economy, 122(6), 1367–1375.

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2017). Secular stagnation? The effect of aging on economic growth in the age of automation (No. w23077). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Albanesi, S., & Olivetti, C. (2014). Maternal health and the baby boom. Quantitative Economics, 5(2), 225–269.

American Heart Association. (2014). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 129, e28–e292.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arking, R. (2006). The biology of aging: Observations and principles. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aghion, P., Howitt, P., & Murtin, F. (2011). The relationship between health and growth: When Lucas meets Nelson-Phelps. Review of Economics and Institutions, 2(1), 1–24.

Ben-Porath, Y. (1967). The production of human capital and the life cycle of earnings. Journal of Political Economy, 75, 352–365.

Bailey, M., Clay, K., Fishback, P., Haines, M., Kantor, S., Severnini, E., & Wentz, A. (2016). U.S. County-level natality and mortality data, 1915–2007. ICPSR36603-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Bhalotra, S. R., & Venkataramani, A. (2015). Shadows of the captain of the men of death: Early life health, human capital investment and institutions. Working paper.

Bleakley, H. (2007). Disease and development: Evidence from hookworm eradication in the American South. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 73–117.

Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Fink, G. (2014). Disease and development revisited. Journal of Political Economy, 122(6), 1355–1366.

Carnes, B. A., & Olshansky, S. J. (2007). A realist view of aging, mortality, and future longevity. Population and Development Review, 33, 367–381.

Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372.

Cervellati, M., & Sunde, U. (2011). Life expectancy and economic growth: The role of the demographic transition. Journal of Economic Growth, 16, 99–133.

Cervellati, M., & Sunde, U. (2013). Life expectancy, schooling, and lifetime labor supply: Theory and evidence revisited. Econometrica, 81, 2055–2086.

Cutler, D. M., Deaton, A., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). The determinants of mortality. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(3), 9–120.

Cutler, D. M., Lleras-Muney, A., & Vogl, T. (2011). Socioeconomic status and health: dimensions and mechanisms. In S. Glied & P. C. Smith (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of health economics (pp. 124–163). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dantas, A. P., Jimenez-Altayo, F., & Vila, E. (2012). Vascular aging: Facts and factors. Frontiers in Physiology, 3, 1–2.

DHHS. (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Decline in deaths from heart disease and stroke–United States, 1900–1999, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48, 649–646.

DHHS. (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Decline in Deaths from Heart Disease and Stroke-United States, 1900–1999, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48, 986–993.

Doepke, M. (2005). Child mortality and fertility decline: Does the Barro-Becker model fit the facts? Journal of Population Economics, 18, 337–366.

Foege, W. H. (1987). Public health: Moving from debt to legacy. American Journal of Public Health, 77, 1276–1278.

Galor, O. (2011). Unified growth theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Galor, O. (2012). The demographic transition: Causes and consequences. Cliometrica, 6(1), 1–28.

Gavrilov, L. A., & Gavrilova, N. S. (1991). The biology of human life span: A quantitative approach. London: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Grossman, M. (2006). Education and nonmarket outcomes. Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 577–633). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Grove, R. D., & Hetzel, A. M. (1968). Vital statistics rates in the United States 1940–1960 (p. 1968). Washington: United States Government Printing Office.

Hansen, C. W. (2013). Life expectancy and human capital: Evidence from the international epidemiological transition. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1142–1152.

Hansen, C. W. (2014). Cause of death and development in the US. Journal of Development Economics, 109, 143–153.

Hansen, C. W., & Lønstrup, L. (2012). Can higher life expectancy induce more schooling and earlier retirement? Journal of Population Economics, 25, 1249–1264.

Hansen, C. W., & Lønstrup, L. (2015). The rise in life expectancy and economic growth in the 20th century. Economic Journal, 125(584), 838–852.

Honoré, B. E., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). Bounds in competing risks models and the war on cancer. Econometrica, 74(6), 1675–1698.

Hazan, M. (2009). Longevity and lifetime labor supply: Evidence and implications. Econometrica, 77, 1829–1863.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S. (2002). Does the mortality decline promote economic growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 7(4), 411–439.

Kirkwood, T. B. L. (1999). Time of our lives: The science of human aging. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lorentzen, P., McMillan, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2008). Death and development. Journal of Economic Growth, 13, 81–124.

Meara, E. R., Richards, S., & Cutler, D. M. (2008). The gap gets bigger: Changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs, 27, 350–360.

Mozaffarian, D., Benjamin, E. J., Go, A. S., Arnett, D. K., Blaha, M. J., Cushman, M., et al. (2015). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation, 131(4), e29–e322.

Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., & Powell, D. (2016). The Effect of population aging on economic growth, the labor force and productivity (No. w22452). National Bureau of Economic Research.

NCHS (2014). National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/.

NHLBI (2012). Morbidity and mortality chart book, national heart, lung, and blood institute. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/research/reports/2012-mortality-chart-book.htm.

Oeppen, J., & Vaupel, J. W. (2002). Broken limits to life expectancy. Science, 296, 1029–1031.

Olshansky, S. J., & Ault, A. B. (1986). The fourth stage of the epidemiologic transition: The age of delayed degenerative diseases. Milbank Quarterly, 64, 355–391.

Omran, A. R. (1971). The epidemiologic transition: A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Quarterly, 49, 509–538.

Omran, A. R. (1998). The epidemiologic transition theory revisited thirty years later. World Health Statistics Quarterly, 51, 99–119.

Oster, E., Shoulson, I., & Dorsey, E. R. (2013). Limited life expectancy, human capital and health investments. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1977–2002.

Ruggles, S., Genadek, K., Goeken, R., Grover, R., & Sobek, M. (2015). Integrated public use microdata series: version 6.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Strulik, H. (2016). The return to education in terms of wealth and health. Discussion paper: University of Goettingen.

Strulik, H., & Vollmer, S. (2013). Long-run trends of human aging and longevity. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1303–1323.

Strulik, H., & Weisdorf, J. (2014). How child costs and survival shaped the industrial revolution and the demographic transition. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 18, 114–144.

Strulik, H., & Werner, K. (2016). 50 Is the new 30–Long-run trends of schooling and retirement explained by human aging. Journal of Economic Growth, 21, 165–187.

Thelle, D. S. (2011). Case fatality of acute myocardial infarction: An emerging gender gap. European Journal of Epidemiology, 26, 829–831.

Ungvari, Z., Kaley, G., de Cabo, R., Sonntag, W. E., & Csiszar, A. (2010). Mechanisms of vascular aging: New perspectives. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65, 1028–1041.

USPHS. (1964). Smoking and health: Report of the advisory committee to the surgeon general of the public health service. Public health service publication no. 1103, United States.

Vallin, J., & Mesle, F. (2009). The segmented trend line of highest life expectancies. Population and Development Review, 35(1), 159–187.

WHO. (2008). The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We would like to thank Carl-Johan Dalgaard, Peter Sandholt Jensen, Sophia Kan, Lars Lønstrup, Uwe Sunde, participants at the 2015 EEA congress in Mannheim, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, C.W., Strulik, H. Life expectancy and education: evidence from the cardiovascular revolution. J Econ Growth 22, 421–450 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-017-9147-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-017-9147-x