Abstract

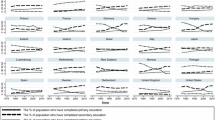

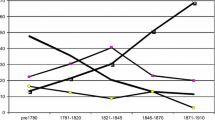

This paper constructs an original database on physical capital, labor, education, GDP, innovations, technology spillovers, and institutions to analyze the proximate determinants of British economic growth since 1270. Several approaches are taken in the paper to tackle endogeneity. We show that education has been the most important driver of income growth during the period 1270–2010, followed by knowledge stock and fixed capital, while institutions have not been robust determinants of growth. The contribution of education has been equally important before and after the first Industrial Revolution. Overall, the results give strong support to the predictions of Unified Growth Theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Apprenticeships and on-the-job training are also important sources of human capital. Madsen (2016) also considers apprenticeships in his estimations; however, the lack of long continuous data makes it difficult to make firm conclusions from the estimates.

A potential concern in this specification is the assumption that the coefficient of capital stock is constant when it may actually have increased over time and, as a result, underestimates the contribution to income of capital stock and overestimates the contribution of the other variables. However, Clark’s (2010) estimates of capital’s income share give no indication of an upward trend in capital’s income share over time. Clark (2010, Table 13) finds capital’s income share to be 31.9% in 1270 and 27.2% in 1860.

Annual hours worked times number of full-time employed would, in theory, be a better measure of labor inputs than employment because it accounts for all dimensions of labor inputs. However, the data on annual hours are controversial and have raised lots of debate in the literature. De Vries (1994) advances the idea that the labor supply increased substantially in North-Western Europe during the Industrial Revolution and earlier; particularly due to more working days per year and increased child labor. Allen and Weisdorf (2011) argue that working days have increased substantially since 1270 and were heavily influenced by the removal of 49 holy days in 1536 associated with the Protestant Reformation. Clark and Van Der Werf (1998), on the other hand, argue that there is no clear evidence of an increase in working days between the middle ages and the nineteenth century. Allen and Weisdorf (2011) compute the working year by estimating how many urban and rural laborer work days are required to achieve a fixed basket of basic consumption. Thus, the days worked a year is essentially a constant times the inverse of real wages, and workers are, consequently, assumed to increase the demand for leisure while holding consumption constant in response to increased real wages; an assumption that is very strong indeed. Regressions using various measures of GDP per hour worked as the dependent variable give results that are consistent to the results obtained above (see, for regression results, Madsen 2016).

In the early nineteenth century and before, there is quite a lot of information about endowed primary and secondary schools but very little data available for the great many private-venture schools including classical grammar, non-classical schools with courses of education aimed at business and navigation and such, as well elementary schools, parish schools, dissenter’s schools and dame schools etc. Although no doubt numerous, these schools were often short lived and left very few, if any, records. A further problem is that when data is available on the number of students, it most often only includes the students studying for free and, thus, excludes the fee paying students who were often in the majority (where they are shown), though their numbers also vary wildly from none upwards.

Historically, reading was always taught first and learning to write was a separate skill that was taught after reading was mastered, if it was taught at all. Spufford (1979), using Cressy’s (1977) literacy statistics inferred from the ability to sign marriage certificates between 1580 and 1700, asserts that those who could sign were educated at a minimum of at least 2, and probably 3, years of education. Citing Cressy, Spufford notes the following ‘literacy’ statistics based on the ability to write: Females 11%, labourers 15%, husbandmen 21%, tradesmen 56% and yeomen 65%. However, Spufford (1979) suggests that these figures ignore a much larger percentage of mainly lower class people, who would only have attended school for 1 or 2 years, but who would have learnt to read in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as females who were often only taught to read regardless of the length of their education. Spufford (1979) supports this assertion with evidence citing numerous examples of very poor, and working class readers, the enormous quantity, and the widespread distribution of chapbooks (small very cheap books aimed predominantly at the working classes), as well as almanacs and ballad sheets. Furthermore, Raymond (2003) suggests that as “the abililty to read print was more common than the ability to read manuscripts and the ability to write.....the many tradesmen, craftsmen and even artisans who lived in London and were able to read became the new patrons of the cheap print” (p. 47). Note, however, that chapbooks and almanacs were distributed in large numbers across the whole country, and there is no reason to believe that the target audience was any different outside of London.

Between 1250 and 1350 in Holkham, for example, there are records of a significant number of transactions of peasants and towns people, suggesting that even people from socially lower ranks were given incentives to learn to read and write (Britnell 2004). Furthermore, there was a substantial increase in manorial record keeping from the thirteenth century, recording such things as cash receipts, expenses, and inventories (Britnell 2004, p. 273).

As in almost all other chronologies of great innovations, Ochoa and Corey (1997) do not discuss the criteria used to select significant innovations. To investigate whether the results are sensitive to alternative classification systems, the stock of knowledge computed from the classification of great innovations of Hellemans and Bunch (1991), Gascoigne (1984), and Asimov (1982) were used as alternative measures of knowledge stock in the regressions reported in Madsen (2016). The principal results are unaffected by this consideration.

The j-group (post-1800 estimates) consists of the 18 OECD core OECD members (Canada, the US, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK), while the 16 countries in the k-group (pre-1800 estimates) consist of India, the US, Denmark, Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Poland, Russia, Portugal, Italy, West Indies, Turkey, and Argentina.

Per capita income at the time at which the working age population with a primary education, \(i \in (0-49)\), or cohort income, is estimated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} ({Y/P})_t^P =\frac{\mathop \sum \nolimits _{i\,=\,0}^{49} \left[ {Pop_{15+i} \mathop \sum \nolimits _{j\,=\,4}^9 \left[ {\left( {\frac{Y}{Pop}} \right) \cdot GER^{P}} \right] _{t-i-j} } \right] }{50\left[ {\mathop \sum \nolimits _{i\,=\,0}^{49} Pop_{15+i} } \right] \cdot \left[ {\mathop \sum \nolimits _{j\,=\,4}^9 [{GER^{P}}]_{t-i-j} } \right] }, \end{aligned}$$(6)where \({(Y/Pop)}^{p}\) is per capita income for the working age population with a primary education (henceforth, cohort income), \({Pop}_{15+i}\) is the size of the population aged \(15+i\), and \({\textit{GER}}^{P}\) is gross enrollment rates at the primary level, estimated as student enrollment at a given year divided by the population of primary school enrollment age. The term, \(Pop_{n,15+i} \mathop \sum \nolimits _{j\,=\,4}^9 GER_{t-i-j}^P \), is the total primary educational attainment of the 15+i age cohort at time t, where \(\mathop \sum \nolimits _{j\,=\,4}^9 GER_{t-i-j}^P \) is primary school educational attainment of this age cohort. For the 64 year olds in 1570, for example, the primary educational attainment is the sum of GERs over the period 1512–1518. The term \(Pop_{15+i} \mathop \sum \nolimits _{j\,=\,4}^9 [ {( {\frac{Y}{Pop}} )\cdot GER^{P}} ]_{t-i-j} \), is the weighted sum of per capita income at the time at which the population of working age did its primary education, weighted by the fraction of each working age cohort that was enrolled in primary school at grade \(j - 3,\,j = 3-9\).

The equations for secondary and tertiary education are not shown for brevity, however, they follow the same principle as Eq. (6). The school ages are 6–11 for primary schooling, 12–14 for secondary schooling up to around 1902. School reforms in the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century change the years of schooling at the primary, secondary and the tertiary levels from the 6–4–5 model to the 7–5–5 model. This is incorporated into the estimates of educational attainment with breaking point in 1902. Note that (Y/Pop) in Eq. (6) is used in the per capita income regressions, while Y is used instead of (Y/Pop) in the income regressions.

See, for example, Weber (1905); Becker et al. (1990); Aghion and Howitt (1992, 2009); Goodfriend and McDermott (1998); Galor and Weil (2000); Galor and Moav (2002, 2004); Tamura (2002); Cervellati and Sunde (2005, 2011); Clark (2005, 2007); Boucekkine et al. (2007); Baten and van Zanden (2008); Khan and Sokoloff (2008); Galor (2011); and Squicciarini and Voigtländer (2015).

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S. & Robinson, J. (2002). The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change, and economic growth, MIT, Department of Economics, Working Paper No. 02–43.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown Publishers.

Achen, C. H. (2000). Why lagged dependent variables can suppress the explanatory power of other independent variables. In Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the Political Methodology Section of the American Political Science Association, University of California at Los Angeles, July 20–22.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60, 323–351.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (2009). The economics of growth. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Allen, R. C. (2003). Progress and poverty in early modern Europe. The Economic History Review, 56(3), 403–443.

Allen, R. C., & Weisdorf, J. L. (2011). Was there an ‘industrious revolution’ before the industrial revolution? An empirical exercise for England, c. 1300–1830. Economic History Review, 64(3), 715–729.

Amiti, M., & Konings, J. (2007). Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs, and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1611–1638.

Ang, J. B., Banerjee, R., & Madsen, J. B. (2013). Innovation, technological change and the British agricultural revolution. Southern Economic Journal, 80(1), 162–186.

Asimov, I. (1982). Asimov’s biographical encyclopedia of science and technology. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company Inc.

Barnard, J., & Bell, M. (2002). The English provinces. In J. Barnard & D. F. McKenzie (Eds.), The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume IV 1557–1695 (pp. 665–686). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Baten, J., & van Zanden, J. (2008). Book production and the onset of modern economic growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 13(3), 217–235.

Becker, G. S., Murphy, K. M., & Tamura, R. (1990). Human capital, fertility, and economic growth. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S12–S37.

Becker, S. O., Hornung, E., & Woessmann, L. (2011). Education and catch-up in the Industrial Revolution. American Economic Journal Macroeconomics, 3, 92–126.

Bils, M., & Klenow, P. J. (2000). Does schooling cause growth? American Economic Review, 90(5), 1160–1183.

Boli, J., Ramirez, F. O., & Meyer, J. W. (1985). Explaining the origins and expansion of mass education. Comparative Education Review, 29(2), 145–170.

Boucekkine, R., de la Croix, D., & Peeters, D. (2007). Early literacy achievements, population density and the transition to modern growth. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(1), 183–226.

Britnell, R. (2004). Britain and Ireland 1050–1530. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Broadberry, S., Campbell, B. M. S., Klein, A., Overton, M., & van Leeuwen, B. (2015). British economic growth 1270–1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carlisle, N. (1818). A concise description of the grammar schools in England and Wales (Vol. 1–2). London: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy.

Cervellati, M., & Sunde, U. (2005). Human capital formation, life expectancy and the process of development. American Economic Review, 95(5), 1653–1672.

Cervellati, M., & Sunde, U. (2011). Life expectancy and economic growth: The role of the demographic transition. Journal of Economic Growth, 16(2), 99–133.

Clark, G. (2005). The condition of the working-class in England, 1200–2000. Journal of Political Economy, 113(6), 1307–1340.

Clark, G. (2007). A farewell to alms: A brief economic history of the world. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clark, G. (2010). The macroeconomic aggregates for England, 1209–2008. Research in Economic History, 27, 51–140.

Clark, G., & Van Der Werf, Y. (1998). Work in progress? The industrial revolution. The Journal of Economic History, 58(03), 830–843.

Coe, D. T., & Helpman, E. (1995). International R & D spillovers. European Economic Review, 39(5), 859–897.

Cohen, D., & Soto, M. (2007). Growth and human capital: Good data, good results. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 51–76.

Conley, T. G., Hansen, C. B., & Rossi, P. E. (2012). Plausibly exogenous. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1), 260–272.

Craig, J. E. (1981). The expansion of education. Review of Research in Education, 9, 151–213.

Cressy, D. (1977). Levels of illiteracy in England, 1530–1730. The Historical Journal, 20(1), 1–23.

Cressy, D. (1980). Literacy and the social order: Reading and writing in Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

David, P. A. (1990). The dynamo and the computer: an historical perspective on the modern productivity paradox. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 80(2), 355–361.

De Montmorency, J. E. G. (1904). The progress of education in England: A sketch of the development of English educational organization from early times to 1904. London: Knight and Co.

De Vries, J. (1994). The industrial revolution and the industrious revolution. Journal of Economic History, 54(2), 249–270.

Doepke, M. (2004). Accounting for fertility decline during the transition to growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 347–383.

Galor, O. (2005). From stagnation to growth: Unified growth theory. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (pp. 171–293). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Galor, O. (2011). Unified growth theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2002). Natural selection and the origin of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1133–1191.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2004). From physical to human capital accumulation: Inequality and the process of development. Review of Economic Studies, 71(4), 1001–1026.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2006). Das human-kapital: A theory of the demise of the class structure. Review of Economic Studies, 73(1), 85–117.

Galor, O., Moav, O., & Vollrath, D. (2009). Inequality in landownership, the emergence of human-capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Review of Economic Studies, 76(1), 143–179.

Galor, O., & Weil, D. N. (2000). Population, technology, and growth: from Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond. American Economic Review, 90(4), 806–828.

Gascoigne, R. M. (1984). A historical catalogue of scientists and scientific books: From the earliest times to the close of the nineteenth century. New York: Garland Pub.

Glaeser, E. L., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2004). Do institutions cause growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 271–303.

Goodfriend, M., & McDermott, J. (1998). Industrial development and the convergence question. American Economic Review, 88(5), 1277–89.

Graff, Harvey J. (1987). The legacies of literacy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Green, A. (1990). Education and state formation: The rise of educational systems in England, France and the USA. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Greenwood, J. (1999). The third industrial revolution: Technology, productivity, and income inequality. Economic Review (pp. 2–12). QII : Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Hans, N. (1951). New trends in education in the eighteenth century. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd.

Hansen, G. D., & Prescott, E. C. (2002). Malthus to Solow. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1205–1217.

Hellemans, A., & Bunch, B. (1991). The timetables of science: A chronology of the most important people and events in the history of science. New York: Simon and Schuster Inc.

Humphries, J. (2010). Childhood and child labour in the British industrial revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacob, M. C. (1988). The cultural meaning of the scientific revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Jacob, M. C. (1997). Scientific culture and the making of the industrial West. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jacob, M. C. (2014). The first knowledge economy: Human capital and the European economy, 1750–1850. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Khan, B. Z. (2015). Knowledge, human capital and economic development: Evidence from the British Industrial Revolution, 1750–1930, NBER Working Paper 20853. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Khan, B. Z., & Sokoloff, K. L. (2008). A tale of two countries: Innovation and incentives among great inventors in Britain and the United States, 1750–1930. In R. Farmer (Ed.), Macroeconomics in the small and the large (pp. 140–156). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Klein Goldewijk, K., Beusen, A., van Drecht, G., & de Vos, M. (2011). The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human induced land use change over the past 12,000 years. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 20(1), 73–86.

Lagerlof, N. P. (2006). The Galor–Weil model revisited: A quantitative exploration. Review of Economic Dynamics, 9(1), 116–149.

Landes, D. S. (1983). Revolution in time: Clocks and the making of the modern world. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Leach, A. F. (1896). English Schools at the reformation 1546–1548. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co.

Lyon, B. (1960). A constitutional and legal history of medieval England. New York: Harper and Brothers.

Maddison, A. (2003). The world economy: Historical statistics. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Madsen, J. B. (2007). Technology spillover through trade and TFP convergence: 135 years of evidence for the OECD countries. Journal of International Economics, 72(2), 464–480.

Madsen, J. B. (2008). Semi-endogenous versus Schumpeterian growth models: Testing the knowledge production function using international data. Journal of Economic Growth, 13(1), 1–26.

Madsen, J. B. (2014). Human capital, and the world technology frontier. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(4), 676–692.

Madsen, J. B. (2016). Human accomplishment and growth in Britain since 1270: The role of great scientists and education. Monash University Working Paper No. 01–16.

Madsen, J. B., & Davis, E. P. (2006). Equity prices, productivity growth and the new economy. The Economic Journal, 116(513), 791–811.

Maitland, F. W. (1963). The constitutional history of England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maurin, E. (2002). The impact of parental income on early schooling transitions: A re-examination using data over three generations. Journal of Public Economics, 85(3), 301–332.

Meisenzahl, R. R., & Mokyr, J. (2012). The rate and direction of invention in the British industrial revolution: Incentives and institutions. In J. Lerner & S. Stern (Eds.), The rate and direction of inventive activity revisited (pp. 443–479). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mitch, D. (1993). The role of human capital in the first Industrial Revolution: In J. Mokyr (Ed.), The British Industrial Revolution: An economic perspective (pp. 267–307). Boulder: Westview Press.

Mokyr, J. (2002). The gifts of Athena. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mokyr, J. (2005a). Long-term economic growth and the history of technology. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (pp. 1113–1180). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Mokyr, J. (2005b). The intellectual origins of modern economic growth. The Journal of Economic History, 65, 285–351.

Mokyr, J. (2009). The enlightened economy: An economic history of Britain, 1700–1850. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mokyr, J., & Voth, H. J. (2009). Understanding growth in Europe, 1700–1870: Theory and evidence. In S. Broadberry & K. H. O’Rourke (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of modern Europe (Vol. 1, pp. 7–42). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moran, J. A. H. (1985). The growth of English schooling 1340–1548: Learning literacy, and laicization in pre-reformation York Diocese. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Morrisson, C., & Murtin, F. (2009). The century of education. Journal of Human Capital, 3(1), 1–42.

Morrisson, C., & Murtin, F. (2013). The Kuznets curve of human capital inequality: 1870–2010. Journal of Economic Inequality, 3(1), 1–42.

Murtin, F., & Wacziarg, R. (2014). The democratic transition. Journal of Economic Growth, 19, 141–181.

Musson, A. E., & Robinson, E. (1969/1994). Science and technology in the industrial revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Reprint, New York: Gordon and Breach.

Newey, W. K., & West, K. D. (1994). Automatic lag selection in covariance matrix estimation. Review of Economic Studies, 61, 631–653.

Nicholas, S. J., & Nicholas, J. M. (1992). Male literacy, ‘deskilling’, and the industrial revolution. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 23(1), 1–18.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. The Journal of Economic History, 49(04), 803–832.

Ochoa, G., & Corey, M. (1997). The Wilson chronology of science and technology. New York: Wilson.

Orme, N. (1989). Education and society in medieval and renaissance England. London: Hambledon Press.

Orme, N. (2006). Medieval schools: From Roman Britain to renaissance England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Peretto, P. (2015). From Smith to Schumpeter: A theory of take-off and convergence to sustained growth. European Economic Review, 78, 1–26.

Raymond, J. (2003). Pamphelets and pamphleteering in early modern Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reis, J. (2005). Economic growth, human capital formation and consumption in Western Europe before 1800. In R. C. Allen, T. Bengtsson, & M. Dribe (Eds.), Living standards in the past: New perspectives on well-being in Asia and Europe (pp. 195–227). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sandberg, L. G. (1979). The case of the impoverished sophisticate: Human capital and Swedish economic growth before World War I. Journal of Economic History, 39(1), 225–241.

Sanderson, M. (1972). Literacy and social mobility in the industrial revolution in England. Past and Present, 56, 75–104.

Sanderson, M. (1991). Education, economic change and society in England 1780–1870 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan.

Schools Inquiry Commission. (1868). Report of the commissioners (Vol. I). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Simmons, R. C. (2002). ABCs, almanacs, ballads, chapbooks, popular piety and textbooks. In J. Barnard & D. F. McKenzie (Eds.), The Cambridge history of the book in Britain, volume IV, 1557–1695 (pp. 504–513). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spufford, M. (1979). First steps in literacy: The reading and writing experiences of the humblest seventeenth-century spiritual autobiographers. Social History, 4(3), 407–435.

Squicciarini, M. P., & Voigtländer, N. (2015). Human capital and industrialization: Evidence from the age of enlightenment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(4), 1825–1883.

Stephens, W. B. (1998). Education in Britain, 1750–1914. London: Macmillan.

Stock, J., & Watson, M. W. (1993). A simple estimator of cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econometrica, 61(4), 783–820.

Stone, L. (1964). The educational revolution in England 1560–1640. Past and Present, 28, 41–80.

Stone, L. (1969). Literacy and education in England 1640–1900. Past and Present, 42, 69–139.

Stowe, A. M. (1908). English grammar schools in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Sullivan, R. J. (1984). Measurement of English farming technological change, 1523–1900. Explorations in Economic History, 21, 270–289.

Tamura, R. (2002). Human capital and the switch from agriculture to industry. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 27(2), 207–222.

Watson, F. (1908). English grammar schools to 1660: Their curriculum and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weber, M. (1905). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. London: Unwin Hyman.

Woodberry, R. D. (2012). The missionary roots of liberal democracy. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 244–274.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Helpful comments and suggestions from Olivier Accominotti, Yann Algan, Steven Broadberry, Markus Bruekner, Neil Cummins, David Fielding, John Gibson, Serguei Guriev, Pietro Peretto, Romain Ranciere, Max Schulze, seminar participants at London School of Economics, Singapore National University, Queensland University of Technology, Sciences-Po Paris, Paris School of Economics, University of Southern Denmark, University of Science Malaysia, participants at the Otago Development Workshop December 2013, The Australasia Development Economics Workshop, Perth (Australia) 2014, The Australasia Public Choice Conference in Singapore, December 2013, and, particularly, Oded Galor and seven referees, are gratefully acknowledged. Stoja Andric, Lisa Chan, Christian Stassen Eriksen, Nancy Kong, Thandi Ndhlela, Christian Rothmann, Ainura Tursunalieva, Cong Wang, Eric Yan, and especially Paula Madsen provided excellent research assistance. Jakob Madsen conducted a great deal of the work on this paper while he was a resident of IMéRA, University of Aix-Marseille in the second half of 2016 and is grateful for the hospitality. Jakob Madsen acknowledges financial support from the Australian Research Council (ARC Discovery Grant Nos. DP110101871 and DP150100061).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Madsen, J.B., Murtin, F. British economic growth since 1270: the role of education. J Econ Growth 22, 229–272 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-017-9145-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-017-9145-z