Abstract

Many factors influence resident physician communication, including rigorous training demands that can contribute to professionalism issues or burnout. The University of Rochester Physician Communication Coaching program launched for attendings in 2011, and expanded to residency programs within 11 clinical departments of our institution. In this model, psychologists serve as coaches, drawing on their expertise in communication skills, behavior change, and wellness promotion. These coaches conduct real-time observation of patient encounters, coding communication with an expanded Cambridge-Calgary Patient-Centered Observational Checklist. Residents receive a written report with individualized feedback. From 2013 to 2020, 279 residents were coached. Since 2018, residents have been formally surveyed for feedback (n = 70 surveys completed; 61% response rate), with 97% rating the experience Very Helpful or Helpful. Of the 70 completed surveys, 54 (77%) included qualitative feedback that has also been positive. Due to the feasibility and growing demand for communication coaching from other residency and fellowship programs, in 2018 two authors (SM and LD-R) developed a 2-year, part-time program to train communication coaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the Institute of Medicine’s (now the National Academy of Medicine’s) 2001 emphasis on communication skills to promote patient-centeredness and satisfaction (Institute of Medicine, 2001), a robust literature on communication and patient satisfaction has emerged (Allenbaugh et al., 2019; Anderson et al., 2007; Beach et al., 2006; Boissy et al., 2016; Mauksch et al., 2008). While communication is formally taught in medical school education (Makoul, 2003), communication remains challenging for residents and other physicians. Psychologists, especially those at academic health centers, often have the competency and skill for teaching communication (Kaslow et al., 2008).

Many factors affect communication with patients, families, and teams, including competing demands of residency training: time pressures, clinical volume, patient complexity and acuity, and resultant physical and emotional fatigue. In response to these challenges, we extended an innovative, clinical communication coaching program for physician faculty to assess feasibility and acceptability with University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) residents. This program uses trained psychologist coaches to assess and improve residents’ communication skills. Senior coaches provide communication coaching for attendings across the Medical Center. Junior faculty and postdoctoral psychologist coaches are embedded in residency programs also to address important health system goals including patient satisfaction, healthcare quality, and resident work-life satisfaction (Bodenheimer & Sinksy, 2014; Spinelli, 2013). As such, the coaching program contributes to a culture of feedback and self-improvement.

The University of Rochester Physician Communication Coaching Program

Dr. McDaniel developed the UR Physician Communication Coaching program in 2011 to enhance physician faculty skills in patient- and family-centered communication and improve the patient care experience. A pilot study focused on three skills associated with patient satisfaction and quality measures: Introduce yourself; elicit patient/family Concerns; and check for patient/family Understanding (or “ICU”). Results revealed differences in how high and low Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHP) scorers communicated with their patients on “ICU” behaviors (McDaniel et al., 2020). The program grew rapidly. In 2016, the URMC GME Senior Associate Dean and multiple Residency Program Directors requested the program be adapted for residents. Subsequently, the senior and second authors (SM and LD-R) began training communication coaches who are now embedded in multiple clinical departments throughout the medical center.

Psychologists as Communication Coaches

Psychologists are particularly well-suited to function as communication coaches. We are trained in clinical observation, behavior change, and understand the foundations of effective communication. Psychologists think systemically, use relational frames to conceptualize behavior, and understand factors that influence behavior change (motivation, confidence, skills, and modeling) (McDaniel et al., 2014). These skills allow psychologists to construct and deliver feedback in an individualized, developmental, and constructive manner. Kaslow et al. (2008) describe several competencies for psychologists in academic health centers that align with the communication coaching role. First, psychologists as teachers are in positions to train other healthcare professionals about communication, power hierarchies, group dynamics, and conflict management as essential to team functioning. Communication coaches maintain professional identities as medical educators and regularly incorporate these principles into conceptualizing communication behaviors with patients, families, and/or teams.

Consultation is another functional competency domain for psychologists in academic health centers (Kaslow et al., 2008). As of 2021, our communication coaches are embedded in 11 clinical departments of our medical center. Residency programs that have not historically hired behavioral scientists or psychologists have partnered with our program, demonstrating of the acceptability of the communication coaching role. These partnerships have resulted secondary faculty appointments and fellowship training opportunities within our institution. Coaches embedded in residency programs include psychologists, some faculty physicians, and psychology fellows, all of whom have completed or are currently completing a 2-year part-time coaching training program. Currently our psychology fellows have communication coaching built into their fellowship training experience to promote several of these core competencies for psychologists in academic health centers. This role requires experience as a psychotherapist and a medical educator such that postdoctoral fellows are the most junior trainees we believe are appropriate. Coaches must also have a solid professional identity to manage medical/system hierarchy, know how to navigate resistance, and have appropriate boundaries, all of which require more training than practicum. Communication coaching is a manifestation of many psychologists’ aims in academic healthcare settings to competently take on new roles using interpersonal skills and psychological expertise, and becoming visible, relevant, and integral in academic medical centers (Hong & Robiner, 2016).

Communication Coaching and the “Hidden Curriculum”

Medical school typically emphasizes communication skill development early in students’ education but less so as training progresses, possibly contributing to decreasing empathy through medical school (Hojat et al., 2004). Additionally, the “hidden curriculum” influences physician identity development as students absorb the commonly held “understandings” driven by institutional, systemic, and cultural guidelines (Hafferty, 1998). Trainees may enter residency with well-developed knowledge about pathophysiology and differential diagnosis, but less prepared for the self-reflection, professionalism, and interpersonal communication skills important for residency success (Lyss-Lerman et al., 2009).

Communication training tools address some, but not all, of these broader medical education challenges. Some tools use behaviorally-anchored checklists, record qualitative data (Keen et al., 2015) and offer coaching on specific communication skills (Brock et al., 2011) or a broader patient encounter framework (Kurtz et al., 2003). These approaches emphasize repeated observation of skills in real-time, to identify strengths, habits, and professional blind spots (Gawande, 2011; Mauksch et al., 2008). The URMC communication coaching program builds on these tools, providing a “deep dive” into patient, family, and team communication with individualized feedback for the resident. Coaching can be useful in various contexts: outpatient, inpatient, the operating room, intensive care units, and the emergency department.

Professionalism can be difficult to teach (Huffmyer & Kirk, 2017; Phillips & Dalgarno, 2017) as it focuses on behaviors and communication that determine the quality of patient, family, and collegial relationships. Professionalism behaviors include responsiveness and compassion to patient and family needs (Irby & Hamstra, 2016) while communicating clearly and respectfully with colleagues. Communication and professionalism issues can reflect skill deficits and underlying wellness concerns. Resident burnout is common (60%) (Dyrbye et al., 2014) and can manifest as diminished empathy (Wallace et al., 2009) and increased irritability, abruptness, and objectification (Passalacqua & Segrin, 2012). Recognizing this, ACGME proposed adjusting the professionalism milestones to include self-awareness and help-seeking subcompetencies (Edgar et al., 2018). Communication coaching can identify wellness concerns early, connect residents to resources to prevent and address burnout, and support positive patient and physician outcomes (Boissy et al., 2016; Gazelle et al., 2015). Our embedded coaches in residency programs are positioned optimally to promote the ACGME educational commitment to professionalism (Chervenak et al., 2018) and address conflicts that can emerge between the “hidden” and explicit curriculum.

Case Illustration

The following vignette illustrates how communication can suffer when a fatigued, stressed resident without strong communication skills works with a patient and family. In this example, the residents’ physician-centered approach resulted in unprofessional, disrespectful interactions with others. He did not partner effectively and ultimately hurt his relationship with his team. Finally, his limited self-awareness prevented recognition of his own deteriorated well-being, precluding him from seeking help from team members. The story is a composite of actual experience in resident communication coaching, using factitious names:

Inpatient nurses paged 3 rd year Medicine resident, Dr. Resident, several times regarding Mr. Jackson’s care. Busy with other patients, he forgot to respond. At 10 pm, he remembered the Jackson family was waiting. Though tired, he went to the unit. A nurse said, “Good, you finally made it! I hope they stuck around.” Frustrated, he snapped, “What do you mean, you hope they’re here? Didn’t you tell them I was busy?”

Dr. Resident entered Mr. Jackson’s room; he was asleep with his wife sitting nearby. Dr. Resident said, “Mr. Jackson, wake up! You wanted to speak to me? Did you want me to talk to … it’s your wife, right?” Mr. Jackson barely nodded before dozing off again. Dr. Resident (Dr. R) sighed and turned to Mrs. Jackson (Mrs. J): “Is there something I can help with?” Exhausted and worried about her husband, she replied, “You are….?”

Dr. R: I’m the resident overseeing your husband’s care.

Mrs. J: Your team said conversations about my husband’s treatment need to go through you. My daughter has a lot of questions.

Dr. R: And they are…?

Mrs. J: You’ll have to ask her.

Dr. R: I’ll be back tomorrow.

Mrs. J: She can’t be here then. Can we call her now? I don’t understand what’s happening.

Dr. R: I’ve had a long day. My team knows the plan regarding your husband’s care… I don’t have time to look at his chart now.

Mrs. J: But…

Dr. R interrupted: See you tomorrow. If you need anything, tell the nurse.

Mrs. Jackson called the nurse and shared what happened. The nurse contacted the attending who quickly developed a care plan and called the daughter to answer her questions. The attending emailed Dr. Resident, providing feedback about her understanding of the day’s events and the poor communication observed by multiple parties; she copied in the Residency Program Director. This was the 2nd complaint about Dr. Resident. Dr. Director met with Dr. Resident the next day. She inquired about what happened, and asked more generally about how he was doing. Dr. Resident felt he had done nothing wrong: “I was tired. You say I can’t work past 80 hours, so I set some boundaries.” Dr. Director expressed concern about the event and suggested that the resident meet with the program’s communication coach. Dr. Director spoke with Dr. Coach about the resident and then emailed both, asking them to work together.

Dr. Resident’s interactions with the patient, family, team, and program leadership suggest growth opportunities in several ACGME milestones universal to residency programs, including Interpersonal and Communication Skills (ICS) and Professionalism (PROF) (Edgar et al., 2018). Residency leaders regularly face similar situations in which skill development may reduce risk of communication problems, work hour violations, exhaustion, or mood disorders (Passalacqua & Segrin, 2012). Communication coaching provides direct assessment and functional evaluation of these milestones and skills.

Materials and Methods

The standardized five-step coaching process for residents is described in Table 1. Coaches arrange a 4-h observation of resident clinical work, write a comprehensive report, and meet with residents to discuss communication strengths, growth areas, and strategies to improve identified communication skills. Residents are encouraged to fill out an anonymous online survey asking them to rate the degree of helpfulness for their coaching feedback (not helpful, somewhat unhelpful, neither helpful nor unhelpful, helpful, or very helpful). They are also given an open-text field to include additional comments about the coaching program. The survey evaluation for this program with residents was reviewed by the University of Rochester Research Subject Review Board and determined not human subject research.

The clinical setting in which the coaching occurs can vary depending on the clinical learning environment (ambulatory, inpatient, surgical, acute care settings) and the identified learning needs of the individual. Many residents participate in the standard coaching process once/year. Some are coached more frequently for ongoing skill development once a domain or potential improvement area is identified, with the next coaching session further individualized. For most residents, the purpose of communication coaching is formative, for their own learning. Thus the written report is shared with the resident only, with Program Directors informed of the milestones achieved. Exceptions occur if a resident has significant problems, with coaching designated as part of a remediation plan. In these cases, the resident receives the full report and feedback shared with faculty focuses on areas of concern.

Results

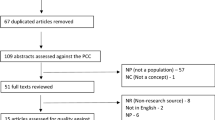

URMC coaches assess the resident’s development as a communicator and deliver constructive and supportive feedback, accounting for each discipline’s culture, practice, team dynamics, pace, and expectations. From 2013 to 2020, 279 residents have been coached from nine programs. Coaching is offered as an innovative educational opportunity supported by residency programs. Residency and coaching leadership collaborate on decisions about coaching timing based on program need and coaching availability. One hundred percent of eligible residents participated in communication coaching as these programs now require all residents to be coached at least once during their training. See Fig. 1 for residents’ ratings on the program. Of 70 surveys completed (response rate 61%), 97% of residents rated the experience Very Helpful or Helpful. Fifty-four of the 70 surveys (77%) also included qualitative comments such as: “The coaching was a good way to learn things about how I am with patients and colleagues in ways that I am not always self-aware….” See Table 2 for resident comments. Returning to our illustration:

Dr. Coach observed Dr. Resident with patients, families, and his team. She compiled a detailed report. During feedback, Dr. Coach emphasized his strengths, including interacting well with patients and team members individually. She noted opportunities for growth when multiple people were in the room, specifically acknowledging everyone, gathering their perspectives, and ensuring that plans were realistic and acceptable to patients and families. She gave feedback related to professionalism, such as timing the meeting when the patient is awake and the family alert and available. They discussed strategies for maintaining a professional stance, despite frustrations or workload. Dr. Coach shared evaluations of Dr. Resident’s competencies in relevant milestone domains.

Dr. Coach also discussed how well-being is directly tied to one’s ability to bring empathy, compassion, and patient- and family-centered care to one’s work. Dr. Resident shared significant family stress and noted he felt overwhelmed. Dr. Coach suggested he might benefit from meeting with a therapist that many residents had found helpful. She normalized this experience, noting that others found it useful to learn stress management strategies. Dr. Resident was interested and took contact information for behavioral health services within the institution. Dr. Coach reviewed with him the brief report she would share with program leaders. This summary included his communication strengths and opportunities for growth, his willingness for future coaching, and with his permission, the impact of personal stressors on his functioning and his acceptance of a referral for support.

Discussion

The UR Physician Communication Coaching program is well-received by residents and educational leadership. It has expanded, now including coaches embedded into 11 residency programs with regular coaching requests from additional residency programs. Since professionalism, burnout, and patient satisfaction are interconnected (Panagioti et al., 2018), our coaches’ roles often broaden to teach biopsychosocial, patient-centered, and family systems-oriented patient care approaches, and self-awareness and wellness topics. Our embedded communication coaches also collaborate with residency program directors about systemic or programmatic issues that may contribute to resident burnout and brainstorm wellness-promoting opportunities. Our program builds on other communication training tools (Brock et al., 2011; Keen et al., 2015; Kurtz et al., 2003) through the: (1) depth of individualized feedback delivered in a step-wise fashion over time to promote sustainable behavior change, and (2) embedded coaches who can address systemic and cultural issues to promote professionalism competencies and wellness (e.g., accessibility/acceptability of mental health care for residents, mentoring match). Finally, our psychologist coaches recognize many benefits to this work, including diversity of role and function, novel application of skills, the appreciation of the residents and faculty, and the recognition of psychologists as leaders within academic health centers.

An element critical to our program’s success is that our senior coaching team first provide communication coaching to departmental and program leadership, prior to engaging the residents. Leaders experience the process first-hand, and can testify to the personal and professional benefits of coaching. They normalize the experience, model skills, and help establish a feedback culture, reinforcing that communication is a complex skill worthy of life-long attention. Our “leadership first” approach, the organizational design that all residents receive coaching, and transparency with residents about what feedback will be shared with residency program leadership, all serve to normalize the process and promote psychological safety among medical learners (Torralba & Puder, 2017).

Limitations and Next Steps

Program limitations include not having data on how coaching improves patient outcomes nor generalizability of results to resident training programs outside our institution. An additional limitation to the generalizability of our results is that communication behavior is multifactorial, influenced by residency culture, mentorship and support, and quality/consistency of other feedback residents receive within their programs. One next step will be to gather data on how many communication coaching sessions residents engage in to identify the range and frequency of coaching session repetitions that meet individual goals and program needs.

An ongoing process is expanding our communication coaching training program, as coaching requests within our institution outpace our supply of trained coaches. In response, two authors (SM and LD-R) developed a 2-year, part-time communication coaching training program for appropriate faculty and psychology postdoctoral fellows. Faculty accepted as coaches-in-training already possess skills as medical educators and psychotherapists or behavior change agents. As a result, in 2021 we have seven faculty and five postdoctoral fellows as coaches-in-training, now embedded in residencies in 11 clinical departments, including Surgery, Internal Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Family Medicine, Pediatrics, Neurology, Emergency Medicine, Neurosurgery, Ophthalmology, Orthopaedics, and Psychiatry. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which placed a significant psychological and physical toll on our healthcare settings, coaching requests within our physician faculty coaching program have grown substantially and further reflect the value-added of this type of program in academic health centers.

In sum, physician communication coaching is an educational innovation well-received by residents that can address the complex relationship between communication skills, professionalism, and wellness. Our coaching program provides the dual-benefit of filling an educational gap for residents while simultaneously contributing to programs’ efforts promoting professionalism and wellness.

Data Availability

Survey data available at request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Allenbaugh, J., Corbelli, J., Rack, L., Rubio, D., & Spagnoletti, C. (2019). A brief communication curriculum improves resident and nurse communication skills and patient satisfaction. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34, 1167–1173.

Anderson, R., Barbara, A., & Feldman, S. (2007). What patients want: A content analysis of key qualities that influence patient satisfaction. The Journal of Medical Practice Management, 22, 255–261.

Beach, M. C., Roter, D. L., Wang, N. Y., Duggan, P. S., & Cooper, L. A. (2006). Are physicians’ attitudes of respect accurately perceived by patients and associated with more positive communication behaviors? Patient Education and Counseling, 62, 347–354.

Bodenheimer, T., & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine, 12, 573–576.

Boissy, A., Windover, A. K., Bokar, D., Karafa, M., Neuendorf, K., Frankel, R. M., … Rothberg, M. B. (2016). Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 755–761.

Brock, D. M., Mauksch, L. B., Witteborn, S., Hummel, J., Nagasawa, P., & Robins, L. S. (2011). Effectiveness of intensive physician training in upfront agenda setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 1317.

Chervenak, F. A., McCullough, L. B., & Grünebaum, A. (2018). Preventing incremental drift away from professionalism in graduate medical education. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219, 589-e1.

Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Satele, D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Sloan, J., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2014). Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Academic Medicine, 89, 443–451.

Edgar, L., Roberts, S., & Holmboe, E. (2018). Milestones 2.0: A step forward. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10, 367.

Gawande, A. (2011). Personal best. The New Yorker, 3, 44–53.

Gazelle, G., Liebschutz, J. M., & Riess, H. (2015). Physician burnout: Coaching a way out. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30, 508–513.

Hafferty, F. W. (1998). Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Academic Medicine, 73, 403–407.

Hojat, M., Mangione, S., Nasca, T. J., Rattner, S., Erdmann, J. B., Gonnella, J. S., & Magee, M. (2004). An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Medical Education, 38, 934–941.

Hong, B. A., & Robiner, W. N. (2016). Psychologists in academic health centers and medical centers: Being visible, relevant and integral. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 23, 11–20.

Huffmyer, J. L., & Kirk, S. E. (2017). Professionalism: The “forgotten” core competency. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 125, 378–379.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health care system for the 21st century. National Academy Press.

Irby, D. M., & Hamstra, S. J. (2016). Parting the clouds: Three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Academic Medicine, 91, 1606–1611.

Kaslow, N. J., Dunn, S. E., & Smith, C. O. (2008). Competencies for psychologists in academic health centers (AHCs). Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 15, 18–27.

Keen, M., Cawse-Lucas, J., Carline, J., & Mauksch, L. (2015). Using the patient centered observation form: Evaluation of an online training program. Patient Education and Counseling, 98, 753–761.

Kurtz, S., Silverman, J., Benson, J., & Draper, J. (2003). Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: Enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Academic Medicine, 78, 802–809.

Lyss-Lerman, P., Teherani, A., Aagaard, E., Loeser, H., Cooke, M., & Harper, G. M. (2009). What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Academic Medicine, 84, 823–829.

Makoul, G. (2003). Communication skills education in medical school and beyond. JAMA, 289, 93–93.

Mauksch, L. B., Dugdale, D. C., Dodson, S., & Epstein, R. (2008). Relationship, communication, and efficiency in the medical encounter: Creating a clinical model from a literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 1387–1395.

McDaniel, S. H., DeCaporale-Ryan, L., & Fogarty, C. (2020). A physician communication coaching program: Developing a supportive culture of feedback to sustain and reinvigorate faculty physicians. Families, Systems, & Health, 38, 184–189.

McDaniel, S. H., Grus, C. L., Cubic, B. A., Hunter, C. L., Kearney, L. K., Schuman, C. C., … Johnson, S. B. (2014). Competencies for psychology practice in primary care. American Psychologist, 69, 409.

Panagioti, M., Geraghty, K., Johnson, J., Zhou, A., Panagopoulou, E., Chew-Graham, C., … Esmail, A. (2018). Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178, 1317–1331.

Passalacqua, S. A., & Segrin, C. (2012). The effect of resident physician stress, burnout, and empathy on patient-centered communication during the long-call shift. Health Communication, 27, 449–456.

Phillips, S. P., & Dalgarno, N. (2017). Professionalism, professionalization, expertise and compassion: A qualitative study of medical residents. BMC Medical Education, 17, 1–7.

Spinelli, W. M. (2013). The phantom limb of the triple aim. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 88, 1356.

Torralba, K. D., & Puder, D. (2017). Psychological safety among learners: When connection is more than just communication. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9, 538–539.

Wallace, J. E., Lemaire, J. B., & Ghali, W. A. (2009). Physician wellness: A missing quality indicator. The Lancet, 374, 1714–1721.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to prior senior coach, Colleen Fogarty, MD MSc, now Chair of UR Family Medicine, for her helpful review of this manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM conceived the innovative coaching program and SM and LD-R expanded the program to residency training. AS-G was primary lead on writing original draft and organized re-writes throughout editorial process. AS-G, LD-R, KB, and SM were all involved in project implementation, data collection, original writing of manuscript and results, and editing. AS-G was primary lead on data analysis, with results reviewed and verified with LD-R and SM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Andrea Shamaskin-Garroway, Lauren DeCaporale-Ryan, Keisha Bell and Susan McDaniel declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This study protocol was reviewed by the University of Rochester Research Subject Review Board and determined not human subject research.

Ethical Approval

This study protocol was reviewed by the University of Rochester Research Subject Review Board and determined not human subject research.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Consent provided to publish figure image.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shamaskin-Garroway, A., DeCaporale-Ryan, L., Bell, K. et al. Physician Communication Coaching: How Psychologists can Elevate Skills and Support Resident Education, Professionalism, and Well-being. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 29, 608–615 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-021-09808-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-021-09808-x