Abstract

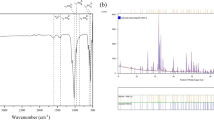

The three-dimensional, highly oriented pore channel anatomy of native rattan (Calamus rotang) was used as a template to fabricate biomorphous hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3OH) ceramics designed for bone regeneration scaffolds. A low viscous hydroxyapatite-sol was prepared from triethyl phosphite and calcium nitrate tetrahydrate and repeatedly vacuum infiltrated into the native template. The template was subsequently pyrolysed at 800°C to form a biocarbon replica of the native tissue. Heat treatment at 1,300°C in air atmosphere caused oxidation of the carbon skeleton and sintering of the hydroxyapatite. SEM analysis confirmed detailed replication of rattan anatomy. Porosity of the samples measured by mercury porosimetry showed a multimodal pore size distribution in the range of 300 nm to 300 μm. Phase composition was determined by XRD and FT-IR revealing hydroxyapatite as the dominant phase with minimum fractions of CaO and Ca3(PO4)2. The biomorphous scaffolds with a total porosity of 70–80% obtained a compressive strength of 3–5 MPa in axial direction and 1–2 MPa in radial direction of the pore channel orientation. Bending strength was determined in a coaxial double ring test resulting in a maximum bending strength of ~2 MPa.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hing KA, Best SM, Bonfield W. Characterization of porous hydroxyapatite. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 1999;10:135–45.

Krajewski A, Mazzocchi M, Buldini PL, Ravaglioli A, Tinti A, Taddei P, et al. Synthesis of carbonated hydroxyapatite: efficiency of the substitution and critical evaluation of analytical methods. J Mol Struct. 2005;744–747:221–8.

Qian J, Kang Y, Zhang W, Li Z. Fabrication, chemical composition change and phase evolution of biomorphic hydroxyapatite. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2008;19:3373–83.

LeGeros RZ. Apatites in biological systems. Prog Cryst Grow Char. 1981;4:1–45.

Hench LL. Bioceramics, from concept to clinic. J Am Ceram Soc. 1991;74:1487–510.

Tampieri A, Celotti G, Landi E, Montevecchi M, Roveri N, Bigi A, et al. Porous phosphate-gelatine composite as bone graft with drug delivery function. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2003;14:623–7.

Moura J, Teixeira LN, Ravagnani C, Peitl O, Zanotto ED, Beloti MM, et al. In vitro osteogenesis on a highly bioactive glass–ceramic (Biosilicate®). J Biomed Mater Res. 2007;82A:545–57.

Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–91.

Hubert SF, Young FA, Mathews RS, Klawitter JJ, Talbert CD, Stelling FH. Potential of ceramic materials as permanently implantable skeletal protheses. J Biomed Mater Res. 1970;4:190–9.

Sopyan I, Kaur J, Toibah JAR, Hamdi M, Ramesh S. Effect of slurry preparation on physical properties of porous hydroxyapatite prepared via polymeric sponge method. Adv Mater Res. 2008;47–50:932–5.

Williams JM, Adewunmi A, Schek RM, Flanagan CL, Krebsbach PH, Feinberg SE, et al. Bone tissue engineering using polycaprolactone scaffolds fabricated via selective laser sintering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4817–27.

Will J, Melcher R, Treul C, Travitzky N, Kneser U, Polykandriotis E, et al. Porous bone scaffolds for vascularized bone tissue regeneration. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2008;19:2781–90.

Kim H-W, Kim H-E, Knowles JC. Production and potential of bioactive glass nanofibers as a next-generation biomaterial. Adv Funct Mater. 2006;16:1529–35.

Helen W, Merry CLR, Blaker JJ, Gough JE. Three-dimensional culture of annulus fibrosus cells within PDLLA/Bioglass® composite foam scaffolds: assessment of cell attachment, proliferation and extracellular matrix production. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2010–20.

Tadic D, Beckmann F, Schwarz K, Epple M. A novel method to produce hydroxyapatite objects with interconnecting porosity that avoids sintering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3335–40.

Vitale Brovarone C, Verné E, Appendino P. Macroporous bioactive glass–ceramic scaffolds for tissue engineering. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2006;17:1069–78.

Deville S, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. Freeze casting of hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5480–9.

Ramay HR, Zhang M. Preparation of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds by combination of the gel-casting and polymer sponge methods. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3293–302.

Murugan R, Panduranga RK, Sampath KTS. Microwave synthesis of bioresorbable carbonated hydroxyapatite using goniopora. Key Eng Mater. 2003;240–242:51–4.

Kannan S, Rocha JHG, Agathopolulos S, Ferreira JMF. Fluorine-substituted hydroxyapatite scaffolds hydrothermally grown from aragonitic cuttlefish bones. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:243.

Worth A, Mucalo M, Horne G, Bruce W, Burbidge H. The evaluation of processed cancellous bovine bone as a bone graft substitute. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16:379–86.

Tampieri A, Sprio S, Ruffini A, Celotti G, Lesci G, Roveri N. From wood to bone: multi step-process to convert wood hierarchical structures into mimetic hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:4973–80.

Singh M, Martínez-Fernández J, de Arellano-López AR. Environmentally conscious ceramics (ecoceramics) from natural wood precursors. Curr Opinion Solid State Mater Sci. 2003;7:247–54.

Sieber H. Biomimetic synthesis of ceramics and ceramic composites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2005;412:43–7.

Cao J. Biotemplating of highly porous oxide ceramics. Göttingen/D: Cuvillier Verlag; 2005.

Rambo CR, Sieber H. Novel synthetic route to biomorphic Al2O3 ceramics. Adv Mater. 2005;17:1088–91.

Jones JR, Hench LL. Regeneration of trabecular bone using porous ceramics. Curr Opinion Solid State Mater Sci. 2003;7:301–7.

Hartung C. Zur Biomechanik weicher Gewebe. VDI Fortschrittsberichte. Reihe Biotechnik. 1975;17(2):91.

Rey C, Collins B, Goehl T, Dickson IR, Glimcher MJ. The carbonate environment in bone mineral: a resolution-enhanced Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:157–64.

Koutsopoulos S. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite crystals: a review study on the analytical methods. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2002;62:600–12.

Liu D-M, Trczynski T, Tseng WJ. Water.based sol–gel synthesis of hydroxyapatite: üprocess development. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1721–30.

Lafon JP, Champion E, Bernache-Assollant D. Processing of AB-type carbonated hydroxyapatite Ca10−x(PO4)6−x(CO3)x(OH)2−x−2y(CO3)y ceramics with controlled composition. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2008;28:139–47.

Welch JH, Gutt W. High-temperature studies of the system calcium oxide-phosphorus pentoxide. J Chem Soc. 1961;IV:4442–4.

Liu D-M, Troczynski T, Tseng WJ. Aging effect on the phase evolution of water-based sol–gel hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1227–36.

de Groot K, Klein CPAT, Wolke JGC, de Blieck Hogervorst JMA. Chemistry of calcium phosphate bioceramics. In: Yamamuro T, Hench LL, Wilson J, editors. CRC handbook of bioactive ceramics, calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite ceramics, vol. II. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1990. p. 3–16.

Gibson LJ, Ashby MF. Cellular solids, structure and properties. New York: Pergammon Press; 1988.

Greil P. Biomorphous ceramics from lignocellulosics. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2001;21:105–18.

Schmitt G, Weiner U, Liese W. The fine structure of the stegmata in Calamus Axillaris during maturation. JAWA J. 1995;16:61–8.

Acknowledgement

The authors greatfully acknowledge the EU commission for the financial support under the FP6 number NMP4-CT-2006-033277.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eichenseer, C., Will, J., Rampf, M. et al. Biomorphous porous hydroxyapatite-ceramics from rattan (Calamus Rotang). J Mater Sci: Mater Med 21, 131–137 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-009-3857-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-009-3857-3