Abstract

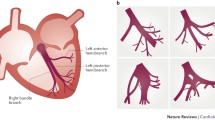

There has always been an appreciation of the role of Purkinje fibers in the fast conduction of the normal cardiac impulse. Here, we briefly update our knowledge of this important set of cardiac cells. We discuss the anatomy of a Purkinje fiber strand, the importance of longitudinal conduction within a strand, circus movement within a strand, conduction, and excitability properties of Purkinjes. At the cell level, we discuss the important components of the ion channel makeup in the nonremodeled Purkinjes of healthy hearts. Finally, we discuss the role of the Purkinjes in forming the heritable arrhythmogenic substrates such as long QT, heritable conduction slowing, CPVT, sQT, and Brugada syndromes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Romero D, Camara O, Sachse F, Sebastian R. Analysis of microstructure of the cardiac conduction system based on three-dimensional confocal microscopy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164093.

Dun W, Lowe JS, Wright P, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ, Boyden PA. Ankyrin-G participates in INa remodeling in myocytes from the border zones of infarcted canine heart. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78087.

Lazzara R, Yeh BK, Samet P. Functional transverse interconnections within the His bundle and the bundle branches. Circ Res. 1973;32:509–15.

Scherlag BJ, El-Sherif N, Hope RR, Lazzara R. The significance of dissociation of conduction in the canine His bundle. Electrophysiological studies in vivo and in vitro. J Electrocardiol. 1978;11:343–54.

Cranefield PF. In. The conduction of the cardiac impulse. The slow response and cardiac arrhythmias. Futura, Mt.Kisco. 1975.

Anderson GJ, Greenspan K, Bandura JP, Fisch C. Asynchrony of conduction within the canine specialized Purkinje fiber system. Circ Res. 1970;27:691–703.

Myerburg RJ, Nilsson K, Befeler B, Castellanos A Jr, Gelband H. Transverse spread and longitudinal dissociation in the distal A-V conducting system. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:885–95.

Mines GR. On circulating excitations in heart muscles and their possible relation to tachycardia and fibrillation. Trans R Soc Can IV 1914; 43–52.

Roberts JD, Gollob MH, Young C, Connors SP, Gray C, Wilton SB, et al. Bundle branch re-entrant ventricular-tachycardia: novel genetic mechanisms in a life-threatening arrhythmia. JACC: Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:276–88.

Nogami A. Purkinje-related arrhythmias part I: monomorphic ventricular tachycardias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:624–50.

Nogami A. Purkinje-related arrhythmias part ii: polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:1034–49.

Sung RK, Boyden PA, Scheinman M. Cellular physiology and clinical manifestations of fascicular arrhythmias in normal hearts. JACC: Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:1343.

Komatsu Y, Nogami A, Kurosaki K, Morishima I, Masuda K, Ozawa T, et al. Fascicular ventricular tachycardia originating from papillary muscles. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e004549.

DRAPER MH, Weidmann S. Cardiac resting and action potentials recorded with an intracellular electrode. J Physiol. 1951;115:74–94.

Myerburg RJ, Nilsson K, Gelband H. Physiology of canine intraventricular conduction and endocardial excitation. Circ Res. 1972;30:217–43.

Pinto JMB, Boyden PA. Electrophysiologic remodeling in ischemia and infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:284–97.

Friedman PL, Fenoglio JJ Jr, Wit AL. Time course for reversal of electrophysiological and ultrastructural abnormalities in subendocardial Purkinje fibers surviving extensive myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res. 1975;36:127–44.

Friedman PL, Stewart JR, Wit AL. Spontaneous and induced arrhythmias in subendocardial Purkinje fibers surviving extensive myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res. 1973;33:612–26.

Bogun F, Good E, Reich S, Elmouchi D, Igic P, Tschopp D, et al. Role of Purkinje fibers in post-infarction ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2500–7.

Nattel S, Maguy A, Le BS, Yeh YH. Arrhythmogenic ion-channel remodeling in the heart: heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:425–56.

Boyden PA, Pu J, Pinto JMB, Ter Keurs HEDJ. Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ waves in Purkinje cells. Role in action potential initiation. Circ Res. 2000;86:448–55.

Han W, Chartier D, Li D, Nattel S. Ionic remodeling of cardiac Purkinje cells by congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2095–100.

Vassalle M, Bocchi L. Differences in ionic currents between canine myocardial and Purkinje cells. Physiological Reports 2013;1. pii; e00036.

Han W, Bao W, Wang Z, Nattel S. Comparison of ion-channel subunit expression in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers and ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 2002;91:790–7.

Jeck C, Pinto JMB, Boyden PA. Transient outward currents in subendocardial Purkinje myocytes surviving in the 24 and 48 hr infarcted heart. Circulation. 1995;92:465–73.

Gadsby DC, Cranefield PF. Two levels of resting potential in cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1977;70:725–46.

Boyden PA, Hirose M, Dun W. Cardiac Purkinje cells. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:127–35.

Robinson RB, Boyden PA, Hoffman BF, Hewett KW. The electrical restitution process in dispersed canine cardiac Purkinje and ventricular cells. Am J Phys. 1987;253:H1018–25.

Boyden PA, Dun W, Stuyvers BD. What is a Ca(2+) wave? Is it like an electrical wave? Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2015;4:35–9.

Boyden PA, Barbhaiya C, Lee T, Ter Keurs HEDJ. Nonuniform Ca2+ transients in arrhythmogenic Purkinje cells that survive in the infarcted canine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:681–93.

Hirose M, Stuyvers BD, Dun W, ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Function of Ca(2+) release channels in Purkinje cells that survive in the infarcted canine heart: a mechanism for triggered Purkinje ectopy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:387–95.

Ter Keurs HEDJ, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457–506.

Laurent G, Saal S, Amarouch MY, Beziau DM, Marsman RFJ, Faivre L, et al. Multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions: a new SCN5A-related cardiac channelopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:144–56.

Mann SA, Castro ML, Ohanian M, Guo G, Zodgekar P, Sheu A, et al. R222Q SCN5A mutation is associated with reversible ventricular ectopy and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1566–73.

Watanabe H, Koopmann TT, Le SS, Yang T, Ingram CR, Schott JJ, et al. Sodium channel beta1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2260–8.

Holst AG, Saber S, Houshmand M, Zaklyazminskaya EV, Wang Y, Jensen HK, et al. Sodium current and potassium transient outward current genes in Brugada syndrome: screening and bioinformatics. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:196–200.

Gaborit N, Le BS, Szuts V, Varro A, Escande D, Nattel S, et al. Regional and tissue specific transcript signatures of ion channel genes in the non-diseased human heart. J Physiol. 2007;582:675–93.

Haissaguerre M, Extramiana F, Hocini M, Cauchemez B, Jais P, Cabrera JA, et al. Mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation associated with long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circulation. 2003;108:925–8.

Sadek MM, Benhayon D, Sureddi R, Chik W, Santangeli P, Supple GE, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the moderator band: electrocardiographic characteristics and treatment by catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:67–75.

Andelfinger G, Tapper AR, Welch RC, Vanoye CG, George AL Jr, Benson DW. KCNJ2 mutation results in Andersen syndrome with sex-specific cardiac and skeletal muscle phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:663–8.

Dun W, Boyden PA. The Purkinje cell; 2008 style. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:617–24.

Makita N, Seki A, Sumitomo N, Chkourko H, Fukuhara S, Watanabe H, et al. A Connexin40 mutation associated with a malignant variant of progressive familial heart block. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:163–72.

Friedrich C, Rinne S, Zumhagen S, Kiper AK, Silbernagel N, Netter MF, et al. Gain-of-function mutation in TASK-4 channels and severe cardiac conduction disorder. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:937–51.

Liu H, El ZL, Kruse M, Guinamard R, Beckmann A, Bozio A, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in TRPM4 cause autosomal dominant isolated cardiac conduction disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:374–85.

Guinamard R, Bouvagnet P, Hof T, Liu H, Simard C, Salle L. TRPM4 in cardiac electrical activity. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;108:21–30.

Iyer V, Roman-Campos D, Sampson KJ, Kang G, Fishman GI, Kass RS. Purkinje cells as sources of arrhythmias in long QT syndrome type 3. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13287.

McPate MJ, Duncan RS, Milnes JT, Witchel HJ, Hancox JC. The N588K-HERG K+ channel mutation in the ‘short QT syndrome’: mechanism of gain-in-function determined at 37 degrees C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:441–9.

Ohno S, Zankov DP, Ding WG, Itoh H, Makiyama T, Doi T, et al. Variants are novel modulators of Brugada syndrome and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation; clinical perspective. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:352–61.

Xiao L, Koopmann TT, Ordog B, Postema PG, Verkerk AO, Iyer V, et al. Unique cardiac Purkinje fiber transient outward current subunit composition; novelty and significance. Circ Res. 2013;112:1310–22.

Sturm AC, Kline CF, Glynn P, Johnson BL, Curran J, Kilic A, et al. Use of whole exome sequencing for the identification of Ito-based arrhythmia mechanism and therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001762.

Priori SG, Napolitano C, Tiso N, Memmi M, Vignati G, Bloise R, et al. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRYR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2000;102:r49–53.

Herron TJ, Milstein ML, Anumonwo J, Priori SG, Jalife J. Purkinje cell calcium dysregulation is the cellular mechanism that underlies catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1122–8.

Laitinen PJ, Brown KM, Piipo K, Swan H, Devaney JM, Brahmbhatt B, et al. Mutations of the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RYR2) gene in familial polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2001;103:r7–r12.

Liu N, Denegri M, Dun W, Boncompagni S, Lodola F, Protasi F, et al. Abnormal propagation of calcium waves and ultrastructural remodeling in recessive catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2013;113:142–52.

Cerrone M, Colombi B, Santoro M, di Barletta MR, Scelsi M, Villani L, et al. Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation elicited in a knock-in mouse model carrier of a mutation in the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res. 2005;96:e77–82.

Willis BC, Pandit SV, Ponce-Balbuena D, Zarzoso M, Guerrero-Serna G, Limbu B, et al. Constitutive intracellular Na+ excess in Purkinje cells promotes arrhythmogenesis at lower levels of stress than ventricular myocytes from mice with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2016;133:2348–59.

Kang G, Giovannone SF, Liu N, Liu FY, Zhang J, Priori SG, et al. Purkinje cells from RyR2 mutant mice are highly arrhythmogenic but responsive to targeted therapy. Circ Res. 2010;107:512–9.

Fujii Y, Itoh H, Ohno S, Murayama T, Kurebayashi N, Aoki H, et al. A type 2 ryanodine receptor variant associated with reduced Ca(2+) release and short-coupled torsades de pointes ventricular arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:98–107.

Jiang D, Chen W, Wang R, Zhang L, Chen SRW. Loss of luminal Ca2+ activation in the cardiac ryanodine receptor is associated with ventricular fibrillation and sudden death. PNAS. 2007;104:18309–14.

Zhao YT, Valdivia CR, Gurrola GB, Powers PP, Willis BC, Moss RL, et al. Arrhythmogenesis in a catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia mutation that depresses ryanodine receptor function. PNAS. 2015;112:E1669–77.

Funding

This work was supported by grants NIH HL114383, HL135754, and HL134824.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boyden, P.A. Purkinje physiology and pathophysiology. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 52, 255–262 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-018-0414-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-018-0414-3