Abstract

The Nordic welfare states are considered advanced in terms of gender equality, but even in these countries women still take longer family leave and have lower earnings than men. This study provides new insights by assessing the differences in accumulated midlife earnings associated with childbearing between women and men in Finland and Sweden. We pay particular attention to the size of the gender gap in accumulated earnings across groups. We hypothesize that the gender gap will be larger among those with a larger number of children, among those with a lower level of education, and overall in Finland. The study is based on complete population register data, with highly accurate measures of earnings over decades. Our results show that by the age of 44, women born in 1974–1975 in Finland and Sweden had earned on average 32% and 29% less than men, respectively. Childbearing strongly modifies the gender gap, especially in Finland, and the highly educated have moderately smaller gaps in both countries. Our results show that, even the Nordic welfare states, despite their strong policy emphasis on gender equality and their success in achieving high levels of female labor force participation, are far from closing the gender gap in earnings accumulated over the first half of the life course. Our results also suggest that governments seeking to achieve gender equality should be cautious about providing long family-related leave with flat-rate compensation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Nordic countries tend to be seen as forerunners in promoting gender equality. This view is supported by the comparatively high labor force participation rates of women and the modest gender gaps in employment rates in these countries (Ferragina, 2019; OECD, 2019). Moreover, the motherhood penalties in terms of wages and earnings tend to be smaller in the Nordics than in some other countries (Cukrowska-Torzewska & Matysiak, 2020; Kleven et al., 2019a, 2019b). However, there is evidence that the penalties are larger in Finland than in Sweden (Budig et al., 2016). Both Finland and Sweden are, like other Nordic countries, often classified as social-democratic welfare states (Gosta Esping-Andersen, 1990; Powell et al., 2020). In particular, the political aims of supporting the combination of employment and childbearing, as well as promoting gender and social equality, are strong characteristics of the Nordic welfare regime (Ellingsæter et al., 2006; Gosta Esping-Andersen, 2009). In support of these aims, benefits are typically provided universally and individuals rather than couples are subject to taxation in the Nordic countries. In terms of family policy, the Nordic countries are known for the provision of comprehensive policies. These include job-protected and income-compensated family-related leaves, universal access to affordable and publicly subsidized childcare to enable mothers and fathers to return to full-time work after childbirth, as well as child-related income support (Daly & Ferragina, 2018). Consequently, the labor force participation levels of women closely resemble those of men and dual-earner families are very common in these countries.

Despite these progressive features of the Nordic countries, there continues to be significant gender inequality in labor market outcomes such as wages, earnings, working hours, and representation in authority positions (Ferragina, 2019; Grönlund et al., 2017). Labor markets in these countries also remain segregated by gender (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2017). Regardless of the Nordics’ emphasis on gender equality in family policies, parenthood is a fundamental source of gender differences in earnings (Cools & Strøm, 2016; Nisén et al., 2022) and authority positions (Bygren & Gähler, 2012; Mandel & Semyonov, 2006). Furthermore, the contribution of the motherhood penalty to the overall gender inequalities in the labor market has increased over time (Kleven et al., 2019a, 2019b). Evidence suggests that, despite their favorable features, extended family leave can hinder subsequent career progression (Evertsson & Duvander, 2011) and lead to larger earnings losses for mothers (Gruber et al., 2023). As a whole, however, levels of earnings inequality remain comparatively moderate (Fritzell et al., 2012). It has been suggested that the earnings trajectories in the Nordic labor markets are explained to a large extent by individuals’ human capital, supporting the idea that Nordic social-democratic welfare state policies are effective in reducing overall labor market inequalities (Hällsten & Yaish, 2022). Indeed, these welfare states have been viewed as successful in facilitating relatively high levels of gender equality as well as social equality at large (Gosta Esping-Andersen, 2009; Korpi, 2000).

Despite the considerable interest in economic gender (in)equality, the issue of gender equality in accumulated earnings has so far received limited attention, especially outside the U.S. context. A recent study estimated that in the U.S., women born in the 1970s accumulated around 60% of earnings relative to men between ages 27 and 35–45 (de Castro Galvao, 2022). The study also found that progress toward closing the gender gap has been slower for cohorts born in the 1960s and 1970s than for earlier U.S. cohorts. Comparative studies related to childbearing, family policy, and the labor market are timely in the context of the Nordic countries, especially in light of the recent unexpected fertility declines that have occurred in these countries despite their well-developed family policies (Hellstrand et al., 2021). Fertility declines have also been reported in many other high-income countries, including in the U.S. (Human Fertility Database, 2022). Moreover, focused comparisons of countries with similar institutional settings, such as the Nordics, have broader significance as they have the potential to identify the reasons for the differences in outcomes between countries (Neyer & Andersson, 2008).

The current study contributes to the existing knowledge on the broader topic of economic gender (in)equality by providing a novel description of how the earnings women and men have accumulated by midlife vary according to their childbearing history (i.e. the number and timing of their children) in two Nordic welfare states. More specifically, using a similar case comparison of Finland and Sweden, we assess the accumulated earnings by age 44 and focus on the gender gaps in this earnings measure across different groups. By assessing earnings accumulation by midlife in recent cohorts of women and men born in 1974–75, we focus on the first half of the life course, which is the target of many welfare state policies, including family policies. Our empirical approach relies on a unique data source: the highly accurate measurement of earnings spanning 25 years from Nordic administrative registers covering the full resident population.

Background

Gendered Accumulation of Earnings over the Life Course

From a life course perspective, it is important to understand how advantages and disadvantages accumulate longitudinally over an individual’s life (DiPrete & Eirich, 2006). Economic advantages can accumulate over the life course to produce larger differences than those measured at a single point in time would suggest (Parolin & VanHeuvelen, 2023). There is growing interest in understanding how gender inequalities in earnings develop cumulatively over the life course (de Castro Galvao, 2022). Earnings accumulated over the life course can be viewed as a comprehensive measure of an individual’s labor market history and accumulated economic resources (Fasang et al., 2024). Accumulated earnings are important determinants of people’s lifestyles, and more broadly of their life chances (Tamborini et al., 2015). Gender differences in accumulated earnings over the life course also contribute to gender differences in wealth accumulation (Ruel & Hauser, 2012), as well as to differences in pension income later in life (Kuivalainen et al., 2020). Moreover, they can be seen as relevant to the relative resources of women and men within couples, since having more accumulated resources may translate into having more bargaining power (see Brines, 1993; Lundborg et al., 2017; Milkie, 2011).

Childbearing can be regarded as a fundamental source of the gender gaps in various indicators of labor market attachment and success, such as earnings levels and the share of women in authority positions (Bygren & Gähler, 2012; Cools & Strøm, 2016; Mandel & Semyonov, 2005, 2006). There is even evidence suggesting that the contribution of childbearing to the gender inequalities in the labor market has increased over time (Kleven et al., 2019a, 2019b). Hence, women and men may be expected to accumulate earnings differently over their life course depending on their childbearing history. The occurrence, as well as the timing, of first-time and subsequent childbearing, is relevant to consider (Huinink & Kohli, 2014). From the life course paradigm follows the core expectation that the life spheres of family and work mutually influence each other over the life course (Bernardi et al., 2019; Fasang et al., 2024). Differences in accumulated earnings based on childbearing are likely to result from processes that include both those leading to the entry into parenthood and the birth of subsequent children (selection), as well as the effects of parenthood on women’s employment, working hours, and wages (Jalovaara & Fasang, 2020; Kolk, 2022). These processes over the individual life course can be viewed as embedded in a broader societal context that both enables and constrains individuals in reaching their goals in different life spheres, such as work and family (Bernardi et al., 2019; Heckhausen & Buchmann, 2019; Huinink & Kohli, 2014). Crucially, it can be hypothesized that the welfare state context affects the extent to which both the processes leading up to childbearing and the impacts of childbearing differ between women and men.

Selection into Childbearing by Earnings in Finland and Sweden

The similar cultural and institutional characteristics of the Nordic countries are believed to have contributed to their similar fertility patterns, which have been characterized by stable and relatively high cohort fertility rates, close to two children, compared to other European countries (Andersson et al., 2009; Hellstrand et al., 2021). In the Nordic countries, the dual-earner model has translated into gender symmetry in the transition to parenthood, such that both women and men with higher education and a stronger attachment to the labor market, including higher earnings, are more likely to enter parenthood (Jalovaara & Miettinen, 2013; Vikat, 2004). An exception to this pattern is that young women with little education and a weak attachment to the labor market have elevated first birth risks (Kreyenfeld & Andersson, 2014; Miettinen & Jalovaara, 2020). For higher order birth risks, positive selection by education or labor market attachment is weak or even negative, such that individuals with a weak attachment to the labor market may even have a slightly elevated risk of having a third birth (Andersson & Scott, 2007; Andersson et al., 2014; Erlandsson, 2017).

Remarkably, in the Nordic countries, gender symmetry in fertility behavior is also observed among those with lower levels of education, who are more likely to remain childless regardless of gender (Jalovaara et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the educational gradient in the eventual number of children is weak among women but is notably positive among men (Jalovaara et al., 2019). However, the differences by educational attainment in the risk of remaining childless are slightly more pronounced in Finland than in Sweden, where women and men are even more similar in this respect (Jalovaara et al., 2022). It has also been suggested that the positive selection of men with higher socioeconomic positions into fatherhood largely explains the so-called fatherhood premium, which refers to fathers having higher employment rates, earnings, and wages on average than childless men (Mari 2019; Van Winkle and Fasang 2020). Data from 2021 show that the mean age at entry into motherhood is close to 30 years in the Nordic countries (except Iceland), including Finland (30.0) and Sweden (30.1) (Statista, 2022). Lifetime childlessness is more common in Finland than in the other Nordics (20% vs 11–13% in the cohorts born in the mid-1970s) (Human Fertility Database, 2022). Moreover, having a large number of children (3 or more) remains somewhat more common in Finland than in the other countries (Jalovaara et al., 2019). Men are more likely than women to enter parenthood later and to remain childless (Dudel & Klüsener, 2021; Jalovaara et al., 2022).

Gendered Practices of Parenting in Finland and Sweden

The Nordic welfare states support the well-being of families and gender equality by providing income-tested and job-protected family-related leave for parents of young children, universal access to affordable childcare, and child-related income support (Daly & Ferragina, 2018). However, there are some important institutional differences between Finland and Sweden that can be hypothesized to lead to differences in parenting practices between these two countries. We hypothesize that such differences will have an impact on the gender gap in accumulated earnings. Taken together, the family policies of Sweden can be considered to support more strongly a dual-earner-carer model (Korpi et al., 2013). Under this model, the provision of public daycare on a full-time basis for children under school age enables mothers to make a continuous and significant commitment to their occupational role (dual-earner dimension). At the same time, fathers are encouraged to take an active role in caring for their minor children through the provision of earnings-related, and possibly earmarked, parental leave (dual-carer dimension). In Finland, there is a stronger emphasis on traditional family policies, which provide general support for families without an emphasis on promoting gender equality in the earning or caring roles.

First, one important difference between the countries lies in the provision and the uptake of parental leave (Duvander et al., 2019). Sweden has a longer history than Finland of providing parental leave with earnings replacement (since 1974 vs since 1985) as well as fathers’ quotas (since 1995 vs since 2003). Sweden has also long provided more weeks of earnings-related parental leave than Finland (16 months vs 9.5 months in 2016), and with a greater degree of flexibility in their take-up. Nonetheless, the differences between the two countries in the length of the maternal and the paternal leave (as quotas for all available parental leave) in 2016 were small (2.2–2.6 months in Finland vs three months in Sweden). The uptake of parental leave remains gender-asymmetrical in both countries, particularly in Finland (Duvander & Lammi-Taskula, 2011). In 2016, fathers took 11% of all available leave days with a daily cash benefit (including maternity and paternity leave) in Finland, while the respective share in Sweden was 28% (NOSOSCO, 2017).

Second, after taking parental leave, parents in Finland continue to have the option to care for their child at home until the child turns three while receiving a flat-rate benefit, referred to as a home care allowance or a cash-for-care benefit. This benefit is accompanied by the guarantee that parents can return to their job after taking home care leave (Hiilamo & Kangas, 2009; Sipila et al., 2010). In Sweden, this benefit was available only briefly in 1994 and 2008–2016 in some municipalities, but the take-up was much lower than in Finland (Ellingsæter, 2014). The home care benefit in Finland is claimed almost exclusively by mothers. It has been criticized for encouraging long spells of mothers outside the labor market (Sipila et al., 2010) and for promoting a more traditional family model (Korpi et al., 2013). Indeed, the employment rate of mothers of young children and the share of children enrolled in publicly subsidized daycare are lower in Finland than in Sweden (Duvander et al., 2021; Eydal & Rostgaard, 2011; Grødem, 2014; Sipila et al., 2010). In 2016, the share of one- to two-year-old children attending childcare was less than 50% in Finland, compared to 70% in Sweden (NOSOSCO, 2017). Nevertheless, while in Sweden part-time work is commonly used by mothers to meet their care responsibilities, in Finland part-time work has not typically been seen as a way to reconcile work and family responsibilities (Grönlund et al., 2017; Rønsen & Sundström, 2002).

Overall, it can be hypothesized that differences in policies are the main drivers of the dissimilar patterns of care and work among parents in the two countries. Yet, differences in cultural norms about the right way to care for children may also play a role (Duvander et al., 2021; Mussino et al., 2019). Indeed, Finland may be culturally more supportive than Sweden of mothers providing home care for children (Hiilamo & Kangas, 2009). In both countries, there is a clear social pattern of women with a stronger labor market attachment returning to work more quickly after childbirth (Evertsson & Duvander, 2011; Kuitto et al., 2019). Moreover, having a partner with a higher level of education and of earnings is positively associated with the take-up of parental leave among fathers (Duvander et al., 2021).

Previous Evidence on Gender Gaps in Accumulated Earnings

Two recent studies from the Nordic context assessed the variation in accumulated earnings, with one focusing on the number of children in Sweden (Kolk, 2022) and the other focusing on the family life course type in Finland (Jalovaara & Fasang, 2020). The Swedish study showed that across cohorts, the relationship between labor earnings accumulated over the lifetime and the number of children has become more similar between genders, with both women and men of the 1970 cohort displaying a reversed U-shaped relationship. While the study did not assess earnings differences by gender, it showed that men had higher earnings than women, even in the most recent cohorts. The Finnish study examined the variation in earnings accumulated by age 39 in the 1969–70 cohorts, and found that fathers who had married late had earned more than other men. Among women, the study observed that mothers who had married late and childless women with a history of cohabitation had higher earnings than other women. However, the authors emphasized that the within-gender differences between groups with different family life courses were modest compared to the overall gender differences in accumulated earnings, which amounted to over 30%.

While evidence from other high-income countries is limited, it also points to notable and even larger gaps in accumulated earnings between women and men. An earlier cross-comparative study predicted smaller gender gaps in accumulated earnings by age 45 in the Nordic countries than elsewhere, with the differences amounting to 32–44% of men’s earnings in Norway and Finland (Sigle-Rushton & Waldfogel, 2007). Differences between mothers and other women, and between mothers of one and two children, were also predicted to be smaller in the Nordic countries than in the other studied countries. Similarly, another cross-country comparison found that for women, the long-term earnings penalty associated with the birth of the first child was highest in German-speaking countries (51–61%), followed by English-speaking countries (31%–44), and was lower in Scandinavian countries (i.e. Denmark and Sweden: 21–26%) (Kleven et al., 2019a, 2019b). In contrast, the study found that parenthood had no long-term effect on men’s earnings. An earlier study estimated that women in the UK would lose on average of 47% of their earnings after becoming mothers, but the loss was much smaller for women with university degrees (Davies et al., 2000). A recent study estimated an overall gender gap in accumulated lifetime earnings in Germany of more than 50%, and an even larger gap among parents with more children (Glaubitz et al., 2022). Previous studies conducted in the U.S. found an overall gap of approximately 40% in accumulated midlife earnings between women and men (de Castro Galvao, 2022), and a larger gap among individuals with lower levels of educational attainment (Kim et al., 2015). Furthermore, while gender gaps in accumulated earnings by the timing of parenthood (i.e. the age at first birth) have not been properly assessed, it has been shown that the later timing of motherhood is associated with higher lifetime earnings in Denmark and Sweden (Cantalini et al., 2017; Leung et al., 2016).

Research Questions

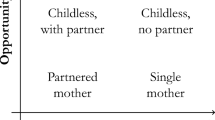

This study utilizes high-quality data from the Finnish and Swedish population registers covering detailed demographic and labor market data on all permanent residents in the respective countries. This study aims to provide a broad description of the gender differences in individual accumulated earnings by midlife associated with childbearing history in two Nordic countries. In doing so, we hope to shed light on the patterns typical of the Nordic social-democratic welfare regime and to highlight any country-specific patterns. We calculate accumulated earnings by gender, childbearing history (i.e. distinguishing between childless, first parity, second parity, and third parity or higher; as well as between early and late parents), and educational attainment. Education is considered primarily an indicator of human capital (Baum, 2002), and a strong correlate of the timing of childbearing (i.e. the age at first birth) (Andersson et al., 2009; Nisén et al., 2014). We study accumulated earnings over the life course at the individual rather than at the household level given the high degree of instability of marital and cohabiting unions in contemporary societies (Härkönen, 2014). We aim to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1 How is childbearing history related to the earnings accumulated by midlife among women and men in two Nordic welfare states?

In both countries, we expect the relationship between the number of children and the accumulated earnings to be positive among men, and to be either negative or to follow a reversed U-shaped pattern among women. This is primarily because we assume that parents are positively selected on education and earnings, but having a larger number of children has additive negative effects on women’s but not men’s careers. The negative effects are partly due to the longer time spent on family leave,Footnote 1 which may facilitate the depreciation and the slower accumulation of human capital (Mincer & Ofek, 1982; Mincer & Polachek, 1974), as well as potential earnings losses during the leave (Baum, 2002). Furthermore, career-oriented women tend to enter motherhood later (Andersson et al., 2009), which may mitigate the accumulation of the negative effects of motherhood (Amuedo-Dorantes & Kimmel, 2005; Bratti & Cavalli, 2014; Doren, 2019). For example, later timing may allow women to establish themselves in the labor market before entering motherhood (Troske & Voicu, 2013).

RQ2 How does the gender gap in accumulated earnings vary by childbearing history in the two welfare states?

In both countries, the gender gap in accumulated earnings is expected to exist regardless of childbearing history, but to be larger among those with more children. In addition to the points raised under RQ1, this expectation is based on occupational gender segregation (Hook et al., 2022), as well as potential statistical discrimination in the labor market (see, e.g. Evertsson & Duvander, 2011), which may affect women’s earnings regardless of their number of children. Furthermore, the later timing of childbearing may decrease the gender gap by reducing the amount of time that motherhood can have a negative impact on the labor market (Cantalini et al., 2017; Leung et al., 2016; Nisén et al., 2022).

RQ3 How does this gender gap vary by educational attainment in the two welfare states?

In both countries, the gender gap in accumulated earnings is expected to be larger among those with lower levels of educational attainment. This expectation follows from the observation that among parents with less education, women are more likely to take long periods of family leave, leave-sharing practices are less gender-symmetrical, and the timing of childbearing is earlier on average. Alternatively, the gender gap could be similar or even wider among highly educated parents, given the larger potential earnings losses due to childbearing and childrearing among more educated women (Buckles, 2008; Lundborg et al., 2017). In addition, the timing may play a greater role for highly educated women, as postponing motherhood might provide additional benefits for their labor market participation. This follows from their (potential) steeper earnings trajectories in the early stages of their careers (Amuedo-Dorantes & Kimmel, 2005; Doren, 2019; Herr, 2016; Miller, 2011) and the importance of timely investments in work experience (Light & Ureta, 1995).

RQ4 Are the gender gaps in accumulated earnings larger or smaller in Finland compared to in Sweden?

The differences based on childbearing history, as well as the overall gender gaps, in accumulated earnings are generally expected to be larger in Finland than in Sweden, given the tendency of Finnish women to take longer periods of family leave after childbirth and the less gender-symmetrical leave-sharing practices in Finland. These country differences in the gender gaps are expected to be more pronounced among parents with a higher number of children. This assumption is primarily based on findings showing the accumulation of negative effects for mothers of multiple children, which are partially attributable to taking several career breaks (Troske & Voicu, 2013). It is also possible that such differences are more visible among individuals who enter parenthood earlier (see Lorentzen et al., 2019), and among less highly educated groups. Mothers with low education are particularly likely to make use of the cash-for-care benefit in Finland, which could have negative effects on their subsequent earnings.

Methodology

Data and Variables

The study is based on high-quality Finnish and Swedish register data covering the total populations residing permanently in these countries. The analytical sample consists of 113,415 individuals born in Finland and 183,946 individuals born in Sweden in 1974–1975. We include women and men who were constantly residing in the country from age 20 until age 44 (i.e. who had not emigrated in any of the analyzed years, and for whom we have information on earnings for each year). The core strength of using individual-level administrative data is that individuals’ earning measures from several years can be combined with other measures, including childbearing history and educational attainment.

Accumulated Earnings

Earnings accumulated by midlife are measured as a total of the annual (gross) work earnings of salaried employees and entrepreneur earnings subject to state taxation between ages 20 and 44 (25 years). This age span covers the period in the life course when individuals typically attain degrees, establish themselves in the labor market, and form families and have children, and thus take family leave from work to care for children. We conduct a sensitivity analysis to see how adding employment-based benefits to the labor earnings influence the gender gaps in accumulated earnings (see the end of the Results section). Employment-based benefits include parental leave benefits (including paternity and maternity leave) and sickness leave benefits, and in the case of Finland, also home care allowance benefits.Footnote 2

We present accumulated earnings based on the price level of 2019 euros. We harmonize our earnings measure to enhance country comparability by first converting annual earnings in Sweden measured in Swedish krona (SEK) to euros using the annual conversion rates provided by Eurostat (Eurostat, 2023a), and by applying the annual rates of living costs to adjust for the differences in these costs between the two countries (Eurostat, 2023). Next, we convert euros from each year into 2019 euros by adjusting for inflation over the years covered (1992–2019) using the Finnish price index (OSF, 2023). We top-code the (gender-specific) 1% of women and men with the highest earnings in both countries in order to avoid the strong influence of outliers (in effect, men with extremely high earnings) on the findings. Of the total analytical samples, 0.6% in Finland 0.5% in Sweden had no earnings. Earnings are reported in thousands of euros.

Childbearing History

We measure an individual’s childbearing history as the total number of children born to the person at the end of the year when she or he turned 44, based on monthly records of births of all registered (biological) children. We group together parents who had three or more children. In addition, to analyze how the timing of childbearing is related to the gender gaps in accumulated earnings among parents, we first group parents by gender. Then, within each gender, we distinguish between late and early parents. Individuals who had their first child at an age below the median are categorized as “early” parents, while those who had their first child at an age above (and including) the median are classified as “late” parents. Education-specific medians are used here given that the average timing of the first birth varies strongly by the level of educational attainment, especially in women (Nisén et al., 2014). Therefore, it can be argued that the same age at first birth has a different meaning depending on the level of education (Andersson et al., 2009). Age 44 generally represents the end of the reproductive life span for women, and very few men have children after this age (Dudel & Klüsener, 2021; Nisén et al., 2014).

Educational Attainment

We distinguish between three levels of educational attainment based on the highest degree attained: low refers to compulsory education only (nine years), medium refers to an academic or vocational higher secondary-level degree (2–3 years), and high refers to an academic or vocational tertiary-level degree (three or more years). The levels of educational attainment used here are conventional in the Nordic context (see, e.g. Jalovaara et al., 2019). For Finland, the information was obtained using Statistics Finland’s register data on the highest completed degree beyond the compulsory basic education (up to nine years), which means that the lowest level was inferred from the fact that the data were missing. The register on educational degrees in Finland is of very high quality, and misclassification of educational attainment based on this procedure is therefore negligible.

Analytical Method

The analysis is based on a description of group-specific means and an assessment of the gender gaps across groups. The gender gap is defined as the difference between women’s and men’s mean earnings relative to the mean earnings of men within a group (in percent). Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix include 95% confidence intervals of all the gender-specific earnings mean estimates. The confidence intervals for men and women do not overlap in any of the studied groups. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using the median instead of the mean (see the end of the Results section).

Results

Childbearing History and Earnings Accumulated by Midlife Among Women and Men (RQ1 & RQ4)

There are relatively large differences in the levels of accumulated earnings between women and men born in Finland and Sweden in 1974–75. In Finland, men have earned on average 763,000 euros by the age of 44, while women have earned 521,000 euros by that age (Table 1). This means that, by the age of 44, on average, Finnish women have earned 32% less than Finnish men. In Sweden, men have earned on average 764,000 euros and women have earned 546,000 euros by age 44, which represents a gender gap of 29%. These findings are particularly noteworthy given that the women in these cohorts are more highly educated than the men, especially in Finland: half of women in Sweden (52%) and over half women in Finland (59%) have attained a tertiary-level degree, compared to only 36% of men in Sweden 39% of men in Finland. Meanwhile, only a small share of men in Finland (11%) and in Sweden (7%) have not attained a secondary degree, and an even smaller share of women have no schooling beyond the compulsory level (5% and 4%, respectively).

In terms of the number of children, men stand out as making up a larger share of those who remain childless in both countries (27% of men vs 19% of women in Finland; 21% of men vs 13% of women in Sweden). However, the levels of childlessness are on average higher in Finland than in Sweden (Table 1). The most common final number of children at age 44 in both countries is two children: in Sweden, 49% of women and 44% of men have two children, while in Finland, 37% of women and 33% of men have two children. Having one child is not common in either country: among both women and men, 16% are one-child parents in Finland and 14% are one-child parents in Sweden. Having three or more children is more common in Finland than in Sweden (28% of women and 24% of men in Finland; 25% of women and 21% of men in Sweden). As expected, the late timing of the first birth is more common among individuals with a lower number of children in both countries.

There is a reversed U-shaped association between the final number of children and the earnings accumulated by age 44, but the strength of this association varies between genders and across countries (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Among both women and men, those with two children have accumulated the highest earnings, but among women, the differences between those with one child and those with no children are small, especially in Finland. Among men, by contrast, parity is strongly positively associated with earnings up to two children. Men and women with three or more children generally earn less than those with two children. This difference is especially large among Finnish women, with those with three or more children earning less than other women. In Sweden, the earnings of women with three or more children are close to the earnings of childless women. Overall, the relationship of the number of children with accumulated earnings by age 44 is more symmetrical by gender in Sweden than in Finland. Among mothers in both countries, those who entered motherhood late have higher earnings than those who entered motherhood early, regardless of their number of children (Table 2). The differences based on the timing of childbearing are less pronounced among fathers, as late fathers do not always earn more than early fathers depending on their number of children.

Further results shown in Fig. 2 (see also Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix) on the absolute levels of earnings highlight, among other things, the similarities in the levels of earnings of highly educated mothers and low educated fathers. For instance, in both countries, the accumulated earnings by age 44 of highly educated mothers of two children are similar to those of low educated men. This finding is remarkable especially given that highly educated mothers make up 48% and 45% of all women in Finland and Sweden, respectively, while low educated fathers make up only 7% and 5% of all men in these countries, respectively.

Variation in the Gender Gap by Childbearing History (RQ2 & RQ4)

Figure 3 shows that the differences in absolute levels of earnings within and between genders translate into notable earnings gaps in relative terms. For earnings accumulated by age 44, there is a positive relationship between the number of children and the gender gap; that is, the gap is larger among parents with a higher number of children. Among the childless, women have accumulated on average only 6% lower earnings than men in Finland and 16% lower earnings than men in Sweden. In both countries, the gender gap among parents with one child is similar, at 25–26% (see also Table 3). Among parents with at least two children, the gender gap is moderately larger in Finland than in Sweden. Among parents with two children—the most common number of children in both countries—mothers have earned on average 35% less than fathers in Finland and 31% less than fathers in Sweden. Among parents of three or more children, the gap is 49% in Finland, but is 10 percentage points smaller, at 39%, in Sweden. In addition, in both countries there are consistently larger gender gaps among early parents. In Finland, this is particularly the case for those with a higher number of children and for those with higher education (Table 3).

Variation in the Gender Gap Across Different Levels of Educational Attainment (RQ3 & RQ4)

The average gender gap is smaller among the higher educated, reaching 44%, 40%, and 35% among the low, medium, and high educated, respectively (Fig. 4 and Table 3), in Finland. Similarly, in Sweden, the gender gap is somewhat larger among the medium educated (33%) than among the high educated (28%), but the gender gap is especially large among the low educated (46%). Thus, the country differences are somewhat more pronounced for the medium and the high educated. Notably, because women are more likely than men to have attained a higher degree in both countries, the overall gender gaps are often smaller than any of the education-specific gaps. A comparison by childbearing history and educational attainment shows that in both countries, women, regardless of their education, have earned the least relative to men in the same category when they have three or more children. In Finland, the gender gap exceeds 50% among the low and the medium educated, but even the high educated mothers of three or more children have earned 49% less than the high educated fathers. In Sweden, the corresponding gender gaps are 37–43% among the medium to high educated and 56% among the low educated. In Sweden, the gender gap is relatively large among low educated childless individuals and one-child parents, but it is worth noting that these groups make up only a small share of the total population of the cohorts born in the mid-1970s. In both countries, the group-specific gender differences are smallest among the highly educated and the childless, with women in these categories earning 14% and 13% less than men in Finland and Sweden, respectively.

The magnitude of the gender gap differs between early and late parents (Fig. 5 and Table 3). In Finland, the timing of childbearing (i.e. the age at the first birth) plays a larger role for those with high education than for those with low or medium education: the differences between early and late parents amount to 5–8 percentage points among the high educated and to 0–6 percentage points among the medium to low educated. The timing plays a greater role for parents with a larger number of children, among whom the gender gaps are generally wider. In Sweden, the difference between early and late parents is more similar across educational groups and parities (7–10 percentage-point difference). In Table 3, most of the gender gaps within groups characterized by a certain childbearing history are smaller on average (Total column) than those within groups stratified by education. This is a consequence of the positive relationship between education and earnings, combined with the higher average levels of educational attainment among women, especially in the case of Finland.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results presented above are based on labor earnings and do not include social transfers. Sensitivity analyses in which employment-based benefits (including parental leave benefits) have been added to the labor earnings are shown in Table 4 (see also Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 in the Appendix). This analysis shows to what extent the inclusion of the employment-based transfers reduces the gaps. Overall, these publicly funded benefits reduce the gender gaps by four percentage points in both countries. The reduction varies clearly by the number of children, from 0 to 1 percentage points among the childless to three, four, and 6–7 percentage points among parents with one, two, and three or more children, respectively, in both countries. Therefore, the inclusion of benefits modestly attenuates the relationship shown in Fig. 3 in both countries. However, it does not explain away the differences by childbearing history and education, nor the differences between countries (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 in the Appendix). The difference in the gap between childless individuals and parents of three or more children is attenuated from 42 to 36 percentage points in Finland and from 23 to 19 percentage points in Sweden. The reduction is more pronounced among the lower educated, at least in Finland, and thus weakens somewhat the educational differences in the gap compared to the gap excluding benefits. The gaps among early and late parents conditional on educational attainment and the number of children are similarly weakened after the inclusion of benefits in both countries.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis that estimated median instead of mean earnings. The main results with this alternative outcome specification remained very similar in most cases. The average gap based on the median was 33% in Finland and 30% in Sweden, and was thus one percentage point higher than when based on the mean. For persons with zero, one, two, and three or more children, the corresponding gender gaps based on median earnings in percent were 5, 26, 35, and 49 in Finland and 16, 25, 31, and 39 in Sweden. Among the low educated and the childless, the gender gap in Sweden was larger when based on the median because of the many women with very low earnings in this group. We note that the low educated group is very small in Sweden, and is likely more marginalized in the labor market than the respective group in Finland. This group also includes a higher share of second-generation migrants in Sweden (i.e. persons born in Sweden with at least one parent born abroad), which may partially explain why the gender gap in this group is larger in Sweden than in Finland.

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

This study assessed the magnitude of the gender gap in earnings accumulated by midlife associated with childbearing history in two Nordic social-democratic welfare states considered advanced in terms of gender equality. However, as expected, we find a gendered relationship between childbearing and accumulated earnings by age 44 in these countries. This is true especially in Finland, where the low earnings of women with three or more children and childless men stand out (RQ1). Notably, a large average gender gap in accumulated labor earnings is found in both Nordic countries, where women have earned on average 32% less than men in Finland and 29% less than men in Sweden by age 44. This gap is larger than recent cross-sectional estimates of gender gaps in employment, earnings, or wages alone for these countries (Ferragina, 2019; OECD, 2018).Footnote 3 This between-gender gap varies systematically by childbearing history, with the gap being larger among those with a higher number of children (RQ2). As expected, the gender gap is moderately larger among individuals with lower levels of educational attainment in both countries. Nonetheless, the tendency for the gender gap to be larger among those with more children is not consistently observed among the less educated, at least in Sweden. We also find that the later timing of childbearing (i.e. the age at first birth) is associated with a smaller gender gap, in the case of Finland more so for the highly educated (RQ3). Overall, the results are largely in line with our expectations that the less gender-equal practices of paid and unpaid work after childbirth in Finland than in Sweden would contribute to larger gaps in accumulated earnings overall, and particularly among parents with a larger number of children; but also that the later timing of childbearing predicts smaller gender gaps in both countries (RQ4). Additional analyses show that the gender gaps are moderately reduced (on average, by four percentage points) in both countries if employment-based benefits are taken into account. This illustrates how the Nordic welfare states with generous family leave entitlements partly compensate women for their lower earnings from the labor market over their life course.

Implications for Family Policy

Several mechanisms across the life course may contribute to the current findings. These mechanisms include those related to selection into parenthood and higher order parities, as well as the negative effects of childbearing on women’s earnings. While fatherhood premiums may theoretically play a role in the current findings, the positive selection into fatherhood among men in higher socioeconomic positions likely explains much of why fathers have accumulated higher earnings by midlife than childless men (Mari 2019; Van Winkle and Fasang 2020). The current findings suggest that structural mechanisms that produce gender differences in earnings over the life course are also rooted in the Nordic welfare states, and especially in Finland. The gender gaps found in this study can be seen as remarkable given that the dual-earner-carer model is prevalent in both countries, albeit to a somewhat different degrees. We expected the greater gender asymmetry in the take-up of leave and the longer family leave periods in Finland to be among the main reasons for the country differences. Leave periods of longer than a year are almost entirely taken by women in Finland. In support of this argument, recent research has shown that the provision of the home care allowance has a long-term negative impact on the earnings of mothers (compared to fathers) in Finland (Gruber et al., 2023), in part by delaying mothers’ return to employment after childbirth (Österbacka & Räsänen, 2022). The job protection associated with this policy facilitates women’s economic security and re-entry into the labor market, but extended childcare leave on flat-rate compensation is likely to result in long-term earnings losses.

In the two studied countries, compensation of lost earnings during family leave through employment-based benefits reduces gender gaps, especially among parents with a larger number of children. This shows how the Nordic welfare states partially compensate mothers for their lower levels of accumulated earnings by age 44, especially of mothers with multiple children. Nonetheless, notable gender gaps in earnings remain even when this compensation is taken into account. For instance, highly educated mothers of two children still accumulate 31% and 27% lower earnings by age 44 than fathers in Finland and Sweden, respectively. Our results can be seen as supporting to some extent the view that family-related leave policies that allow long job-protected absences from the labor market may have unintended negative implications for gender equality (Mandel & Semyonov, 2005, 2006). Yet, based on the limited evidence available, the gender gaps in accumulated earnings found in the current study are not larger than those documented in other countries—if anything, the gaps appear to be somewhat smaller (see de Castro Galvao, 2022; Glaubitz et al., 2022; Sigle-Rushton & Waldfogel, 2007). Taken together, the current evidence highlights that the Nordic welfare model, despite its strong emphasis on gender equality, has so far been unable to achieve gender parity in earnings accumulated over the first half of the life course. However, there is no evidence to suggest that the Nordic model facilitates larger earnings disparities than other welfare models. Previous evidence indicates that extended leave rights have a limited impact on gender gaps in earnings, with less positive effects being observed at longer leave durations (Ferragina, 2019; Olivetti & Petrongolo, 2017). Very long leaves can be detrimental to economic equality between men and women, especially if the monetary compensation associated with the leave is provided on a relatively low flat-rate basis, which is likely to discourage fathers from taking leave (Duvander et al., 2019; O’Brien & Wall, 2017). By focusing on earnings accumulation over the life course, the current results provide further support for the claim that the provision of cash-for-care benefits does not support a dual earner-carer model (see Korpi et al., 2013).

In both countries, later childbearing is associated with a smaller gender gap in earnings, and in Finland this pattern is more pronounced among the highly educated and among parents with more children. These findings can be interpreted as indicating that women with higher levels of education who entered motherhood relatively early in Finland have experienced larger losses of (potential) earnings. Earlier comparative results for Nordic countries show that young mothers in Finland are at particularly high risk of developing a weak attachment to the labor market over a longer period of time (Lorentzen et al., 2019). The cohorts under investigation here, who were born in the mid-1970s, entered the labor market in the aftermath of the recession of the early 1990s, which was particularly severe in Finland and had a longer-lasting impact on the Finnish economy and society (Ólafsson, 2019). Particularly in Finland, motherhood may have provided a means to seek fulfillment in life for women with uncertain labor market prospects (Miettinen & Jalovaara, 2020; Vikat, 2004). It is also possible that strong occupational gender segregation has contributed to the modest variation in the gender gap by the timing of childbearing observed among Finnish mothers with low to medium levels of education (OECD, 2023). More broadly, the provision of family-related leave periods lasting longer than nine months may facilitate occupational gender segregation, especially among non-tertiary educated mothers (Hook et al., 2022).

It should be emphasized that Finland is a particular case among the Nordic countries in that it has stronger policy incentives—and, perhaps, stronger cultural values—supporting long periods of family leave for mothers. The current results for Sweden are more likely to be representative of the Nordic social-democratic welfare state context at large. However, the gender gap in accumulated earnings varies systematically by childbearing history in Sweden as well, although less strongly than in the case of Finland, from 16% among the childless to 39% among parents with three or more children. Unfortunately, we could not assess the role of part-time work (i.e. work hours) in the current findings due to data limitations. The gender gaps in accumulated earnings among parents working (mainly) full-time are likely to be smaller than the average. Moreover, it has been previously shown that working part-time is one strategy Swedish mothers use to balance work and care, while mothers in Finland are less likely to be in part-time work (Grönlund et al., 2017). Thus, it is plausible that conditional on the mothers’ type of employment (full vs part-time), the differences in the gender gaps in accumulated earnings between the two countries would be larger than those estimated in this study. However, over the last two decades, the difference in the share of women (aged 25–49) working part-time between the countries has converged considerably as a consequence of opposite country trends, from 19 percentage points in 2003 to six percentage points in 2022 (Eurostat, 2023b). The implications of this change warrant further investigation.

Further Implications

Furthermore, lower individual accumulated earnings for mothers are likely to translate into mothers having lower individual savings (e.g. in the form of a housing assets) than fathers, and thus may increase the economic dependence of mothers on their partners. This can in turn mean that mothers have less bargaining power in their relationships than fathers. Thus, the gender gap in accumulated earnings can play a critical role, especially after a divorce or partnership dissolution in which one parent can no longer rely (as strongly as before) on the resources of the other. The current findings also have implications for the later life course. Lower levels of earnings accumulated over the life course generally translate into lower pensions (Davies et al., 2000; Kuivalainen et al., 2020). While receiving the home care allowance in Finland counts as contributing to an employment pension (since 2005), the contribution level is modest compared to that in Sweden (Koskenvuo, 2016). This adds to the economic risk faced by Finnish mothers with long care episodes. At the same time, childless men and women can be considered a vulnerable group at older ages, not least because they may lack potential support from close family members, such as their own children. In the Nordic context, those without children do not have particularly high earnings, which would help them to access alternative means of support (see also Fasang et al., 2024). Childless women with low to medium education and childless men with low education have relatively low earnings, yet in Finland, childless men with medium education earn more than women on average. Thus, it is important to pay attention to the well-being of those without children, especially in light of the increasing levels of childlessness among people with relatively low education in the Nordic context—and given the already high levels of childlessness in Finland (Jalovaara et al., 2019).

The results may have relevance in light of the current low period fertility in Finland (2022: 1.32) (OSF, 2024). We can speculate that institutional support and cultural expectations for long absences from paid work, combined with any issues that women face in establishing themselves in the labor market before (potentially) having children, may have contributed to the country’s current low fertility landscape. All of the Nordic countries, along with many other countries, have recently reported declining fertility rates. However, among the Nordics, Finland ranks highest in terms of the strength of the decline, and it currently has the lowest levels of period and cohort fertility (Hellstrand et al., 2021). The more traditional pattern of parenting in Finland compared to that in Sweden may help to explain the current low fertility landscape of Finland. Norms supporting the long absences of mothers from the labor market in a dual-earner society may lead women to want to get firmly established in the labor market before taking a long break. This argument is bolstered by the observation that in the Nordics, having a strong attachment to the labor market is a prerequisite for entering parenthood regardless of gender. However, the expectation that mothers will take long career breaks may be a barrier to women in establishing their careers at all, as evidenced, for instance, by their higher rates of temporary employment (ILO, 2016). A strongly gendered pattern of leave use combined with the provision of long leaves, as in Finland, can signal to (potential) employers that young women are at risk of taking long career breaks (see Hegewisch & Gornick, 2013).

Furthermore, it is plausible that “normative confusion” around gender roles might contribute to the low period fertility rates in Finland (Gøsta Esping-Andersen & Billari, 2015). Women’s much higher levels of education compared to men’s raise the expectations of women’s earnings—but these are unlikely to be met if it remains the norm that long periods of family leave are taken almost exclusively by women. It would be in line with contemporary theorizing on fertility (Goldscheider et al., 2015; McDonald, 2000; Neyer et al., 2013) to assume that a greater discrepancy between the level of gender equality in the family sphere and the public sphere (i.e. education, employment)—in this case in Finland compared to in Sweden—contributes to lower fertility. Moreover, to the extent that the current results are truly attributable to the effects of childbearing on mothers’ earnings, they imply that the recent fertility declines will reduce the average gender gap in accumulated earnings, especially in Finland.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study shows that childbearing strongly modifies the gender gap in earnings accumulated by midlife in the Nordic welfare state context—especially in Finland—and that the gender gap in accumulated earnings is moderately smaller for highly educated women than for their less educated counterparts. Our results show that despite their strong policy emphasis on gender equality and their success in achieving high levels of female labor force participation, even the Nordic welfare states are far from closing the gender gap in earnings accumulated over the first half of the life course. Our results, based on a comparative analysis, suggest that governments seeking to achieve gender equality should be cautious about providing long family-related leave with flat-rate compensation. It is also important for them to pay attention to the cumulative economic impacts of the uptake of family leave for individuals across educational groups. To support social change aimed at promoting economic gender equality, it is preferable for governments to invest in affordable childcare as well as parental leave with earnings replacement (Ferragina & Seeleib-Kaiser, 2015). The relatively low levels of earnings accumulated by those without children in the Nordic context also deserve attention. We call for more scholarly interest in investigating how economic gender inequalities accumulate across the life course in different welfare state contexts. The disparities in accumulated earnings cannot be captured by cross-sectional estimates of earnings gaps. As data limitations have been among the reasons for the limited prior evidence on gender inequalities in accumulated earnings, the increasing availability of longitudinal individual-level data will be helpful.

Data Availability

The original individual-level data are stored at Statistics Finland and Statistics Sweden and are only available to authorized researchers. For more information about how to request access to these data, please visit https://stat.fi/tup/tutkijapalvelut/index_en.html and https://www.scb.se/en/services/ordering-data-and-statistics/microdata/. The Finnish register data set was analyzed under license number TK-53–1119-17.

Notes

Family leave refers to the combination of parental leave (including maternity/paternity leave) and any home care leave for the care of children taken by a parent after parental leave.

We do not have the information for the year 1994 in Finland, which is the year in which the cohort born in 1975 turns 20. However, this is not likely to bias our findings in any meaningful way given the low levels of fertility at these ages: 5.4% of the Finnish sample had a birth by the end of the year they turned 20.

In 2016, the gender employment gap was below five points in both countries, and the gender wage gap reached 18% in Finland and 13% in Sweden in the population aged 15–64 (OECD, 2018). In 2014, the gender gap in the median earnings of full-time employees in the Nordic countries reached 12% on average (Ferragina, 2019).

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Kimmel, J. (2005). The motherhood wage gap for women in the United States: The importance of college and fertility delay. Review of Economics of the Household, 3, 17–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-004-0978-9

Andersson, G., & Scott, K. (2007). Childbearing dynamics of couples in a universalistic welfare state: The role of labor-market status, country of origin, and gender. Demographic Research, 17, 897–938.

Andersson, G., Rønsen, M., Knudsen, L. B., Lappegård, T., Neyer, G., Skrede, K., Teschner, K., & Vikat, A. (2009). Cohort fertility patterns in the Nordic countries. Demographic Research, 20, 313–352.

Andersson, G., Kreyenfeld, M., & Mika, T. (2014). Welfare state context, female labour-market attachment and childbearing in Germany and Denmark. Journal of Population Research, 31(4), 287–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-014-9135-3

Baum, C. L. (2002). The effect of work interruptions on women’s wages. Labour, 16(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9914.00185

Bernardi, L., Huinink, J., & Settersten, R. A., Jr. (2019). The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 41, 100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.11.004

Bratti, M., & Cavalli, L. (2014). Delayed first birth and new mothers’ labor market outcomes: Evidence from biological fertility shocks. European Journal of Population, 30, 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9301-x

Brines, J. (1993). The exchange value of housework. Rationality and Society, 5(3), 302–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463193005003003

Buckles, K. (2008). Understanding the returns to delayed childbearing for working women. American Economic Review, 98(2), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.403

Budig, M. J., Misra, J., & Boeckmann, I. (2016). Work–family policy trade-offs for mothers? Unpacking the cross-national variation in motherhood earnings penalties. Work and Occupations, 43(2), 119–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888415615385

Bygren, M., & Gähler, M. (2012). Family formation and men’s and women’s attainment of workplace authority. Social Forces, 90(3), 795–816. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sor008

Cantalini, S., Härkönen, J., & Dahlberg, J. (2017). Does postponing Pay Off? Timing of parenthood, earnings trajectories, and earnings accumulation in Sweden. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography. https://doi.org/10.17045/sthlmuni.5484682.v1

Cools, S., & Strøm, M. (2016). Parenthood wage penalties in a double income society. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(2), 391–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9244-y

Cukrowska-Torzewska, E., & Matysiak, A. (2020). The motherhood wage penalty: A meta-analysis. Social Science Research, 88–89, 102416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102416

Daly, M., & Ferragina, E. (2018). Family policy in high-income countries: Five decades of development. Journal of European Social Policy, 28(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717735060

Davies, H., Joshi, H., & Peronaci, R. (2000). Forgone income and motherhood: What do recent British data tell us? Population Studies, 54(3), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/713779094

de Castro Galvao, J. (2022). Gender inequality in lifetime earnings. Social Forces, 101(4), 1772–1802. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soac060

DiPrete, T. A., & Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123127

Doren, C. (2019). Which mothers pay a higher price? Education differences in motherhood wage penalties by parity and fertility timing. Sociological Science, 6, 684–709.

Dudel, C., & Klüsener, S. (2021). Male–female fertility differentials across 17 high-income countries: Insights from a new data resource. European Journal of Population, 37(2), 417–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-020-09575-9

Duvander, A.-Z., Eydal, G. B., Brandth, B., Gíslason, I. V., Lammi-Taskula, J., & Rostgaard, T. (2019). Gender equality: Parental leave design and evaluating its effects on fathers’ participation. In P. Moss, A.-Z. Duvander, & A. Koslowski (Eds.), Parental leave and beyond (pp. 187–204). UK: Policy Press.

Duvander, A.-Z., Mussino, E., & Tervola, J. (2021). Similar negotiations over childcare? A comparative study of fathers’ parental leave use in Finland and Sweden. Societies, 11(3), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030067

Duvander, A.-Z., & Lammi-Taskula, J. (2011). Parental leave, childcare and gender equality in the Nordic countries. In I. Gíslason & G. B. Eydal (Eds.), Nordic Council of Ministers (pp. 29–62).

Ellingsæter, A. L., & Leira, A. (Eds.). (2006). Politicising Parenthood in Scandinavia: Gender Relations in Welfare States. UK: Policy Press.

Ellingsæter, A. L. (2014). Nordic earner-carer models—why stability and instability? Journal of Social Policy, 43(3), 555–574. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727941400021X

Erlandsson, A. (2017). Child home care allowance and the transition to second-and third-order births in Finland. Population Research and Policy Review, 36(4), 607–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-017-9437-1

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). Incomplete Revolution: Adapting Welfare States to Women’s New Roles. Polity Press.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00024.x

European Institute for Gender Equality. (2017). Gender Equality Index 2017 - Measuring gender equality in the European Union 2005-2015. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://doi.org/10.2839/251500

Eurostat. (2023b). Part-time employment as a percentage of the total employment, by sex and age (%) [LFSQ_EPPGA__custom_6361315]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/, accessed 25.5.2023.

Eurostat. (2023a). Euro/national currency exchange rates [TEIMF200]. Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/, accessed 3.3.2023.

Eurostat. (2023c). Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices and real expenditures for ESA 2010 aggregates [PRC_PPP_IND__custom_5154766]. Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/, accessed 3.3.2023.

Evertsson, M., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2011). Parental leave—possibility or trap? Does family leave length effect Swedish women’s labour market opportunities? European Sociological Review, 27(4), 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq018

Eydal, G. B., & Rostgaard, T. (2011). Gender equality revisited–changes in Nordic childcare policies in the 2000s. Social Policy & Administration, 45(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00762.x

Fasang, A. E., Andrade, S. B., Bedük, S., Buyukkececi, Z., & Karhula, A. (2024). Lives in welfare states: Life courses, earnings accumulation, and relative living standards in five European countries. American Journal of Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1086/730851

Ferragina, E. (2019). Does family policy influence women’s employment?: Reviewing the evidence in the field. Political Studies Review, 17(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929917736438

Ferragina, E., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2015). Determinants of a silent (r) evolution: Understanding the expansion of family policy in rich OECD countries. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 22(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxu027

Fritzell, J., Bäckman, O., & Ritakallio, V.-M. (2012). Income inequality and poverty: do the Nordic countries still constitute a family of their own? In J. Kvist, J. Fritzell, B. Hvinden, & O. Kangas (Eds.), Changing social equality: The Nordic welfare model in the 21st century (pp. 165–186). UK: Bristol University Press, Policy Press.

Glaubitz, R., Harnack-Eber, A., & Wetter, M. (2022). The gender gap in lifetime earnings: The role of parenthood. DIW Berlin Discussion Paper, . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4071416

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x

Grødem, A. S. (2014). A review of family demographics and family policies in the Nordic countries. Baltic Journal of Political Science, 3(50), 66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699316660595

Grönlund, A., Halldén, K., & Magnusson, C. (2017). A Scandinavian success story? Women’s labour market outcomes in Denmark, Finland. Norway and Sweden. Acta Sociologica, 60(2), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699316660595

Gruber, J., Kosonen, T., & Huttunen, K. (2023). Paying moms to stay home: Short and long run effects on parents and children. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, 30931. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30931

Hällsten, M., & Yaish, M. (2022). Intergenerational educational mobility and life course economic trajectories in a social democratic welfare state. European Sociological Review, 38(4), 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab054

Härkönen, J. (2014). Divorce: Trends, patterns, causes, and consequences. In J. Treas, J. Scott, & M. Richards (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to the sociology of families (pp. 303–322). NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Heckhausen, J., & Buchmann, M. (2019). A multi-disciplinary model of life-course canalization and agency. Advances in Life Course Research, 41, 100246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.09.002

Hegewisch, A., & Gornick, J. C. (2013). The impact of work-family policies on women’s employment: a review of research from OECD countries. Work and Family Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2011.571395

Hellstrand, J., Nisén, J., Miranda, V., Fallesen, P., Dommermuth, L., & Myrskylä, M. (2021). Not just later, but fewer: Novel trends in cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. Demography, 58(4), 1373–1399. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9373618

Herr, J. L. (2016). Measuring the effect of the timing of first birth on wages. Journal of Population Economics, 29, 39–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-015-0554-z

Hiilamo, H., & Kangas, O. (2009). Trap for women or freedom to choose? The struggle over cash for child care schemes in Finland and Sweden. Journal of Social Policy, 38(3), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279409003067

Hook, J. L., Li, M., Paek, E., & Cotter, B. (2022). National work–family policies and the occupational segregation of women and mothers in European countries, 1999–2016. European Sociological Review, 39(2), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac046

Huinink, J., & Kohli, M. (2014). A life-course approach to fertility. Demographic Research, 30, 1293–1326.

Human Fertility Database. (2022). Human Fertility Database. www.humanfertility.org/com. 7.4.2022. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) and Vienna Institute of Demography (Wittgenstein Centre, Austria).

ILO. (2016). Non-standard employment around the world: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects. International Labour Office. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/417360

Jalovaara, M., & Fasang, A. E. (2020). Family life courses, gender, and mid-life earnings. European Sociological Review, 36(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz057

Jalovaara, M., & Miettinen, A. (2013). Does his paycheck also matter? The socioeconomic resources of co-residential partners and entry into parenthood in Finland. Demographic Research, 28, 881–916.

Jalovaara, M., Neyer, G., Andersson, G., Dahlberg, J., Dommermuth, L., Fallesen, P., & Lappegård, T. (2019). Education, gender, and cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Population, 35(3), 563–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9492-2

Jalovaara, M., Andersson, L., & Miettinen, A. (2022). Parity disparity: Educational differences in Nordic fertility across parities and number of reproductive partners. Population Studies, 76(1), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2021.1887506

Kim, C., Tamborini, C. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Field of study in college and lifetime earnings in the United States. Sociology of Education, 88(4), 320–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040715602132

Kleven, H., Landais, C., Posch, J., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2019a). Child penalties across countries: Evidence and explanations. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109, 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191078

Kleven, H., Landais, C., & Søgaard, J. E. (2019b). Children and gender inequality: Evidence from Denmark. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(4), 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191078

Kolk, M. (2022). The relationship between life-course accumulated income and childbearing of Swedish men and women born 1940–70. Population Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2022.2134578

Korpi, W. (2000). Faces of inequality: Gender, class, and patterns of inequalities in different types of welfare states. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 7(2), 127–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/7.2.127

Korpi, W., Ferrarini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in western countries re-examined. Social Politics, 20(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs028

Koskenvuo, K. (2016). Perhevapaiden vaikutus eläkkeeseen 1980-luvulta 2000-luvulle [Impact of family leaves on pension from the 1980s to the 2000s]. In A. Haataja, I. Airio, M. Saarikallio-Torp, & M. Valaste (Eds.), Laulu 573 566 Perheestä. Lapsiperheet ja Perhepolitiikka 2000-luvulla [A Song of ... Families. Families with Children and Family Policies in the 2000s] (pp. 116–136). Kela.

Kreyenfeld, M., & Andersson, G. (2014). Socioeconomic differences in the unemployment and fertility nexus: Evidence from Denmark and Germany. Advances in Life Course Research, 21, 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2014.01.007

Kuitto, K., Salonen, J., & Helmdag, J. (2019). Gender inequalities in early career trajectories and parental leaves: Evidence from a Nordic welfare state. Social Sciences, 8(9), 253.

Kuivalainen, S., Nivalainen, S., Järnefelt, N., & Kuitto, K. (2020). Length of working life and pension income: Empirical evidence on gender and socioeconomic differences from Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 19(1), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747218000215

Leung, M. Y. M., Groes, F., & Santaeulalia-Llopis, R. (2016). The relationship between age at first birth and mother’s lifetime earnings: Evidence from Danish data. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0146989. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146989

Light, A., & Ureta, M. (1995). Early-career work experience and gender wage differentials. Journal of Labor Economics, 13(1), 121–154. https://doi.org/10.1086/298370

Lorentzen, T., Bäckman, O., Ilmakunnas, I., & Kauppinen, T. (2019). Pathways to adulthood: Sequences in the school-to-work transition in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Social Indicators Research, 141, 1285–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1877-4

Lundborg, P., Plug, E., & Rasmussen, A. W. (2017). Can women have children and a career? IV evidence from IVF treatments. American Economic Review, 107(6), 1611–1637. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141467

Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2005). Family policies, wage structures, and gender gaps: Sources of earnings inequality in 20 countries. American Sociological Review, 70(6), 949–967. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000604

Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2006). A welfare state paradox: State interventions and women’s employment opportunities in 22 countries. American Journal of Sociology, 111(6), 1910–1949. https://doi.org/10.1086/499912

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00427.x

Miettinen, A., & Jalovaara, M. (2020). Unemployment delays first birth but not for all. Life stage and educational differences in the effects of employment uncertainty on first births. Advances in Life Course Research, 43, 100320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2019.100320

Milkie, M. A. (2011). Social and cultural resources for and constraints on new mothers’ marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 18–22.

Miller, A. R. (2011). The effects of motherhood timing on career path. Journal of Population Economics, 24, 1071–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0296-x

Mincer, J., & Ofek, H. (1982). Interrupted work careers: Depreciation and restoration of human capital. Journal of Human Resources, 7(1), 3–24.

Mincer, J., & Polachek, S. (1974). Family investments in human capital: Earnings of women. Journal of Political Economy, 82, S76–S108.

Mussino, E., Tervola, J., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2019). Decomposing the determinants of fathers’ parental leave use: Evidence from migration between Finland and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718792129

Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2008). Consequences of family policies on childbearing behavior: Effects or artifacts? Population and Development Review, 34(4), 699–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00246.x

Neyer, G., Lappegård, T., & Vignoli, D. (2013). Gender equality and fertility: Which equality matters? European Journal of Population, 29, 245–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9292-7

Nisén, J., Martikainen, P., Silventoinen, K., & Myrskylä, M. (2014). Age-specific fertility by educational level in the Finnish male cohort born 1940–1950. Demographic Research, 31, 119–136.

Nisén, J., Bijlsma, M. J., Martikainen, P., Wilson, B., & Myrskylä, M. (2022). The gendered impacts of delayed parenthood: A dynamic analysis of young adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research, 53, 100496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2022.100496

NOSOSCO. (2017). Social Protection in the Nordic Countries. Scope, Expenditure and Financing. Social Protection in the Nordic Countries 2015/2016. Nordic Social Statistical Committee (NOSOSCO). 63:2017. https://nhwstat.org/.

O’Brien, M., & Wall, K. (2017). Comparative Perspectives on Work-Life Balance and Gender Equality: Fathers on Leave Alone. Cham: Springer Nature.

OECD. (2018). OECD Economic Surveys: Finland 2018. OECD Publishing https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-fin-2018-en

OECD. (2019). Employment rate (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/1de68a9b-en, accessed 1.8.2019.

OECD. (2023). Joining Forces for Gender Equality. https://doi.org/10.1787/67d48024-en

Ólafsson, S., Daly, M., Kangas, O., & Palme, J. (Eds.). (2019). Welfare and the Great Recession: A Comparative Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Olivetti, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2017). The economic consequences of family policies: Lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 205–230. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.205

OSF. (2023). Consumer Price Index. Official Statistics Finland (OSF).; Statistics Finland. https://stat.fi/en/statistics/khi. https://stat.fi/en/statistics/khi, accessed 3.3.2023.