Abstract

Households in the United States hold a significant portion of their total wealth in owner-occupied housing. Thus, changes in housing prices may have an important impact on the marital surplus the household enjoys. What happens to marriages of homeowners when there is a shock to housing prices? This question was addressed using household data from the panel study of income dynamics (PSID) and a quarterly MSA level house price index from the Federal Housing Finance Agency, controlling for local labor market conditions. House price shocks were calculated as the cumulative sum of residuals of a second order autoregressive model from the previous four years. Results showed that positive house price shocks stabilized marriage for all couples. A one standard deviation increase in the house price shock decreased the risk of divorce in the following year by about 13–18%. The results were driven by the younger cohort of households in the PSID, those with lower educational attainment, and those with relatively low family income. The findings are discussed in the context of theories on changes in marital surplus, and changes in the transaction costs surrounding divorce.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lovenheim and Mumford (2013) used house price data and restricted-use location data from the panel study of income dynamics (PSID), as in this paper. They showed that increases in housing wealth increase fertility rates for homeowners. Dettling and Kearney (2014) examined the relationship between MSA level housing prices and MSA level fertility rates as well and confirmed an increase in fertility among homeowners.

Data obtained through the Office of Policy Analysis and Research in Washington, DC: Federal Housing and Finance Agency (2012).

Other indexes exist, most notably the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indexes, however they did not fit as well with the goals of this paper. The Case-Shiller index only covered 20 Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the US, and did not begin until the late 1980s or early 1990s, and so there would have been too few observations for analysis.

The index was measured quarterly, so adding the residuals from the past 16 quarters to the current quarter gives us the sum for 4 years. House price shocks of other lengths were tested in the "Results" section.

This was somewhat different to the calculation of house price shocks in Rainer and Smith (2010). Their paper used the methodology presented in Disney et al. (2010) where the house price shocks were calculated as the cumulative residuals of an AR(2) process of the house price index (since the beginning of data collection) with county fixed effects. Unlike the UK House Price data used by Disney et al. (2010) and Rainer and Smith (2010), the All-Transactions Index starts at different dates for different MSAs. Therefore, cumulating the residuals from the start of each MSAs housing data from Eq. 1, as in Rainer and Smith (2010), was not an ideal strategy since different MSAs would have shocks that were summed over different numbers of years. Some MSAs might have had a HPI for only a few years and others might have had a HPI for 10+ years, especially in the later years in the analysis. This would make it more difficult to compare the experiences in one MSA to another. So in this study, instead if some MSA had not existed or had not been collecting housing data for at least 4 years, no shock was measured.

Data obtained through the University of Michigan: Institute for Social Research Survey Research Center (2012).

Unemployment data by MSA was only available beginning in 1990, so county unemployment data was used. In many cases the MSA covered one county, however for some larger MSAs there may have been several counties included.

Note that in the analysis some larger population MSAs were divided into subregions for finer location measures. However, the GIS maps of metropolitan areas grouped all of these subregions one area, so the data illustrated on the maps was the average for the year for the larger areas. The MSAs that were sub-divided in this way in the analysis were Boston, Chicago, Dallas/Ft. Worth, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. A full set of maps for every year is available upon request.

While the inclusion of household fixed effects would have been a natural extension with panel data, they could not be included since nearly all respondents only experienced one divorce, if any. The identification assumptions for duration models disallow the possibility of fixed effects without multiple spells for each individual in the data (Cameron and Trivedi 2005, p.802).

Ideally we want the value of each variable at the date of divorce. A divorce was observed to have occurred between two interviews so the closest date of observation, without going beyond the date of divorce, was the date of the previous interview. Thus, the analysis would not include information that occurred AFTER the date of divorce.

Positive house price shocks also have a significant and negative effect using a logit model or a linear probability model.

To calculate the effect on the divorce hazard in percentage terms, the average probability of divorcing in a given year was 0.0105. A one standard deviation increase in the positive house price shock would have decreased this probability by 0.14 percentage points for the average individual in the sample. So the percent change in the divorce hazard was calculated as \(\frac{0.0105-0.0014}{0.0105}-1=-0.133\) or –13.3%.

This was comparable in magnitude to the effect of a one S.D. negative income shock which decreased the divorce hazard by about 15% as estimated from the author’s working paper titled “The effects of unpredicted changes in income on the probability of divorce.” The effect on the divorce hazard of 13.3% was much larger than what Rainer and Smith (2010) found, but smaller than the effect of job loss as studied by Charles and Stephens (2004).

The results look almost identical if we limit the sample to only the couples who would be included in every one of the four models in Table 4.

As mentioned in the "Data and Methods" section, the summation of residuals to calculate house price shocks was for the past 4 years. Whereas Rainer and Smith (2010) calculated shocks as the continuous sum from the beginning of their sample in 1991. Thus larger positive shocks in the early 2000s may have been balanced out by the relatively flatter housing markets of the 1990s.

Discrete time duration models and continuous time duration models both provide estimates of the divorce hazard, but view the explanatory variables in slightly different ways. Jenkins (1995) stated that for discrete time duration analysis, time-varying variables would be assumed to be constant over the unit of time. This seemed to be a reasonable assumption since most of the time-varying variables did not change very quickly (education, number of children, etc.). In general the time aggregation has not been found to cause significant bias in the estimates for simple parametric approaches (Bergström and Edin 1992).

The difference in sample size between these regressions and those in Table 3 was partially because of the few households who were only observed once in the sample. A household must have been observed at least twice to be included in a Cox Model. The other reason for the difference was the few observations with a zero weight. A Cox Model must have a constant weight for the duration of a marriage, so the average of the weight variable is used, which washed out a zero for 1 year in the weight variable.

One potential issue was that of unobserved heterogeneity, or frailty, in the divorce hazard. There may have been unobserved characteristics about individuals that caused them to have systematic differences in their baseline divorce hazard. In this context, the term “frailty” indicated those “frail” marriages that were less likely to survive. This would have meant that over time only the strongest marriages would have remained in the data. In duration models this unobserved heterogeneity could lead to biased and inconsistent parameter estimates. The results remained similar when allowing for shared frailty (since each household was observed multiple times) in the Column (24) Cox model, showing an estimated hazard of 0.829 with a standard error of (0.085) and significant at the 10% level.

In both regimes, states have a concept of “separate property” which was mainly property/assets obtained by one spouse prior to marriage or through gifts or inheritance that would not be included in the property division decisions. A select few states legally considered all property, regardless of source, to be marital property. However, informally in these states attorneys still tended to exclude property that would have been considered separate in other states from the property division decisions (Ehrlich 2007, p. 362).

References

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(4), 1269–1287. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x.

Amato, P. R., Loomis, L. S., & Booth, A. (1995). Parental divorce, marital conflict, and offspring well-being during early adulthood. Social Forces, 73(3), 895–915. doi:10.1093/sf/73.3.895.

Attanasio, O., Leicester, A., & Wakefield, M. (2011). Do house prices drive consumption growth? The coincident cycles of house prices and consumption in the UK. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 399–435. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01021.x.

Becker, G. S., Landes, E. M., & Michael, R. T. (1977). An economic analysis of marital instability. The Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1141–1187. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1837421.

Bergström, R., & Edin, P.-A. (1992). Time aggregation and the distributional shape of unemployment duration. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 7(1), 5–30. doi:10.1002/jae.3950070104.

Böheim, R., & Ermisch, J. (2001). Partnership dissolution in the UK: The role of economic circumstances. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 63(2), 197–208. doi:10.1111/1468-0084.00216.

Bostic, R., Gabriel, S., & Painter, G. (2009). Housing wealth, financial wealth, and consumption: New evidence from micro data. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(1), 79–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942841.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. J. (1988). The behavior of home buyers in boom and post-boom markets. New England Economic Review. doi:10.3386/w2748.

Charles, K. K., & Stephens, M. (2004). Job displacement, disability, and divorce. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(2), 489–522. doi:10.1086/381258.

Chowdhury, A. (2013). Til recession do us part: Booms, busts and divorce in the United States. Applied Economics Letters, 20(3), 255–261. doi:10.1080/13504851.2012.689104.

Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., Conger, K. J., Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., et al. (1990). Linking economic hardship to marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(3), 643–656. doi:10.2307/352931.

Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B, 34(2), 187–220. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4380-9_37.

Cutright, P. (1971). Income and family events: Marital stability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 33(2), 291–306. doi:10.2307/349415.

Dettling, L. J., & Kearney, M. S. (2014). House prices and birth rates: The impact of the real estate market on the decision to have a baby. Journal of Public Economics, 110, 82–100. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.09.009.

Disney, R., Gathergood, J., & Henley, A. (2010). House price shocks, negative equity, and household consumption in the United Kingdom. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(6), 1179–1207. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00552.x.

Douthat, R. (2009). Marriage and the recession. The New York Times. Retreived from http://douthat.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/12/08/marriage-and-the-recession/.

Ehrlich, J. S. (2007). Family law for paralegals (4th ed.). New York: Aspen Publishers Online.

Farnham, M., Schmidt, L., & Sevak, P. (2011). House prices and marital stability. American Economic Review, 101(3), 615–619. doi:10.1257/aer.101.3.615.

Federal Housing and Finance Agency. (2012). All transactions index, for metropolitan statistical areas and divisions, and state nonmetropolitan areas [data file and codebook]. Washington, DC: Office of Policy Analysis and Research. Retrieved from https://www.fhfa.gov.

Freed, D. J. (1972). Grounds for divorce in the American jurisdictions. Family Law Quarterly, 6(2), 179–212. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25739233.

Freed, D. J., & Foster Jr., H. H. (1979). Divorce in the fifty states: An overview as of 1978. Family Law Quarterly, 13(1), 105–128. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25739107.

Genesove, D., & Mayer, C. J. (1997). Equity and time to sale in the real estate market. American Economic Review, 87(3), 255–69. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2951345.

Gray, J. S. (1998). Divorce-law changes, household bargaining, and married women’s labor supply. The American Economic Review, 88(3), 628–642. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/116853.

Gruber, J. (2004). Is making divorce easier bad for children? The long-run implications of unilateral divorce. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(4), 799–834. doi:10.1086/423155.

Halliday Hardie, J., & Lucas, A. (2010). Economic factors and relationship quality among young couples: Comparing cohabitation and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1141–1154. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00755.x.

Hellerstein, J. K., & Morrill, M. S. (2011). Booms, busts, and divorce. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 11(1), 54. doi:10.2202/1935-1682.2914.

Hurst, E., & Stafford, F. (2004). Home is where the equity is: Mortgage refinancing and household consumption. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(6), 985–1014. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3839098.

Institute for Social Research Survey Research Center (2012). Panel Study of Income Dynamics estricted use data set [data file and codebook] r. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. Retrieved from http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/.

Jacob, H. (1988). Silent revolution: The transformation of divorce law in the United States. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Jenkins, S. P. (1995). Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57(1), 129–138. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.1995.tb00031.x.

Kreider, R. M., & Ellis, R. (2011). Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2009 (pp. 70–125). Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-125.pdf.

Leland, J. (2008). Breaking up is hard to do after housing fall. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/30/us/30divorce.html.

Lovenheim, M. F., & Mumford, K. J. (2013). Do family wealth shocks affect fertility choices? Evidence from the housing market. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 464–475. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00266.

Marinescu, I. (2016). Divorce: What does learning have to do with it? Labour Economics, 38, 90–105. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2016.01.002.

Marvell, T. B. (1989). Divorce and the fault requirement. Law and Society Review, 23(4), 543–568. doi:10.2307/3053847.

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Parker-Pope, T. (2011). For some, a recession-proof marriage. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/07/for-some-a-recession-proof-marriage/?_r=0.

Peters, H. E. (1986). Marriage and divorce: Informational constraints and private contracting. The American Economic Review, 76(3), 437–454. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1813361.

Rainer, H., & Smith, I. (2010). Staying together for the sake of the home?: House price shocks and partnership dissolution in the UK. Journal of The Royal Statistical Society Series A, 173(3), 557–574. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2009.00628.x.

Rotz, D. (2015). Why have divorce rates fallen? The role of women’s age at marriage. Journal of Human Resources. doi:10.3368/jhr.51.4.0214-6224R.

Schaller, J. (2013). For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. Journal of Population Economics, 26(3), 1007–1033. doi:10.1007/s00148-012-0413-0.

Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26(4), 609–643. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1988.tb01520.x.

Skinner, J. (1989). Housing wealth and aggregate saving. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 19(2), 305–324. doi:10.1016/0166-0462(89)90008-2.

Skinner, J. S. (1996). Is housing wealth a sideshow? In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Advances in the economics of aging (pp. 241–272). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stevenson, B. (2007). The impact of divorce laws on marriage-specific capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(1), 75–94. doi:10.1086/508732.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2007). Marriage and divorce: Changes and their driving forces. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 27–52. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30033716.

Thaler, R. H. (1990). Anomalies: Saving, fungibility, and mental accounts. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(1), 193–205. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942841.

Weiss, Y., & Willis, R. J. (1997). Match quality, new information, and marital dissolution. Journal of Labor Economics, 15(1), S293–329. doi:10.1086/209864.

White, L., & Rogers, S. J. (2000). Economic circumstances and family outcomes: A review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1035–1051. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01035.x.

White, L. K. (1990). Determinants of divorce: A review of research in the eighties. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(2), 904–912. doi:10.2307/353309.

Wolff, E. N. (1998). Recent trends in the size distribution of household wealth. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(3), 131–150. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2647036.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for helpful comments and suggestions from Shelly Lundberg, Peter Kuhn, Olivier Deschenes, Kelly Bedard, Maya Rossin-Slater, Kellie Forrester, three anonymous reviewers, and seminar participants at UCSB, the All-California Labor Economics Conference, and the American Economic Association Annual Meeting. Excellent research assistance provided by Paul Jepsen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and Animal Participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Appendix

Appendix

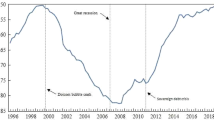

Further Description of House Price Shocks

Further description of the house price shock variable can be provided upon request including distributions of the house price shock over time and more detailed time series graphs which show the considerable variation in the experiences of different locations before, during, and after the housing crisis. Many states had almost no measurable “unexpected” change in housing prices during the housing boom or bust years.

Table 12 examines those couples who did divorce and looked at their outcomes following the divorce. While on average only 2% of households in the data switched from being homeowners to renters, among recent divorcees this percentage was much higher. We saw both men and women spent more money on rent following a divorce and had lower overall expenditures. However, the findings here illustrated in particular the increased financial hardship of those couples who divorced following a positive house price shock. These men and women had even larger increases in rent payments and even larger decreases in food expenditures. Those couples who in fact stayed married following a positive house price shock likely would have faced similar large financial burdens had they divorced. An interesting fact noted in these finding that bears further research was that divorced men spent less on food used at home and childcare, and appeared to substitute preparing meals at home with more meals purchased away from home. Divorced women, on the other hand, spent more on food to be used at home and more on child care.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klein, J. House Price Shocks and Individual Divorce Risk in the United States. J Fam Econ Iss 38, 628–649 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9532-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9532-9