Abstract

In education systems around the globe influenced by neoliberalism, teachers commonly experience reforms which emphasise local responsibility and accountability. Teachers additionally work within what has been described as an era of social acceleration and associated “fast policy”, with a perceived increase in the pace of reform. In this article, we present data drawn from a large (N = 18,234) survey of Australian public-school teachers’ work. Analysis of both quantitative and qualitative reports indicates a widespread teacher perception of workload increase from 2013 to 2017, and the attribution of such increase to the introduction of policy initiatives including, but not limited to, school autonomy reform. Our findings have implications for education policy in Australia and beyond, with an erosion of teacher trust suggesting the need for more sustainable and consultative forms of “slow democracy” in education policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

According to Ball et al., (2012, p. 141), school education today takes place within a “climate of policy overload and initiativitis—in a period of constant reform and incitement to improve.” In this article, we explore teachers’ experiences of policy change in public-school education. We achieve this through examining teachers’ perceptions and lived experience of change to their work and workload, as well as how they attribute the cause of such change, connecting and extending debates regarding school autonomy, teacher accountability, and teacher workload. In doing so, we put forward an analysis which draws together related but heretofore disparate conceptual devices around temporality in policy, located within a broader theoretical context of social acceleration (Rosa, 2003).

Teachers’ work and workload over the period 2013 to 2017 in the state of New South Wales (NSW), Australia provides the empirical forum through which we examine public-school teachers’ experience of policy change. During this time, the “Local Schools, Local Decisions” (LSLD) autonomy and devolution reforms (NSW DEC, 2011) —along with a range of other state and federal policy affecting teachers—were in operation.

In what follows, we present further background regarding the reform context in NSW during the five-year period from 2013 to 2017. We explore literature from Australia and around the globe regarding governance reform in public education systems, as well as that documenting changes to teacher workload. Subsequently we outline our conceptual framework for the article, constructed around ideas of social acceleration, “fast policy”, and policy “layering”. We then detail our research methods before presenting our results and discussion. Ultimately, we argue that this article makes two key contributions. First, teachers report experiencing heightened workload via ongoing policy shifts, such that “policy” is being perceived as synonymous with “change”. This may have significant ramifications for future policy implementation and workplace relations between teachers and their government employer. Second, we seek to contribute to theoretical developments in critical policy studies by drawing together a range of related conceptual devices for considering teachers’ experience of policy change.

Background

Teachers in the Australian state of NSW have been subject to a wide range of reforms over the past ten years. These include, for example, changes to funding structures at both federal and state level,Footnote 1 a move to a national curriculum, the introduction of new literacy and numeracy programs (NSW DEC, 2017), and the institution of new record-keeping procedures for student assessment (NSW Education Standards Authority, 2019). One particularly substantial change during this period was the shift to a new mode of school autonomy via the LSLD initiative. In this section, we consider the research literature relating to change and reform in public education, both in Australia and globally; and the growing body of research around work demands and workload in teaching.

Change and reform in public education

Autonomy reform, where the running of state schools is purportedly “freed up” at the local level, has been an international trend in education, for instance through the Academy model in England (Chitty, 2013) or charter schools in the United States (Ravitch, 2010). Research in Australia has examined whether autonomy promotes or undermines particular forms of justice. Keddie (2017) argues that while school autonomy reforms can support political, cultural and economic justice in better responding to the needs of local communities, it can also undermine social justice by variously silencing and privileging different voices. Principals’ capacity for “moral leadership” is therefore key (Keddie et al., 2018), so that autonomy does not “fracture” relationships between and within school communities (Fitzgerald et al., 2018; Holloway & Keddie, 2019).

Part of understanding the operation of autonomy, then, includes exploration of the effects such policy approaches can have on principals and teachers—and whether and how such impacts can and should be resisted (Gobby et al., 2018). Indeed the “companion” of autonomy, within neoliberal governance approaches at least, tends to be found in centralised modes of accountability (Hashim et al., 2021). According to Ball et al., (2012, p. 9), “much education policy making has been appropriated by the central state in the determination to control, manage and transform education … even if this sometimes involves the appearance of giving away control and enhancing autonomy”. While the “problem of the unaccountable teacher” (Thompson & Cook, 2014, p. 700) is not new, its particular shape and prominence has been rearticulated in current governance models. Autonomy reform is counter-balanced by processes of “responsibilisation”, driving responsibility for the outcomes of education to local levels (including teachers), and establishing particular policy technologies to encode and measure these outcomes. Such “autonomous” systems thereby arguably continue “the reliance on, yet suspicion of, the teacher” (Thompson & Cook, 2014, p. 704) in new ways. This contradictory combination of effects is what is often referred to as “remote control” governance (Connell, 2013) or “steering at a distance” (Rizvi & Lingard, 2010, p. 119). As Ball (1990, p. 68) put it, writing thirty years ago in the context of autonomy reform in England, while matters such as the curriculum may be made “national”, “accountability is now firmly local”.

Sometimes, there is a direct relation between autonomy and accountability, for instance in the institution of principal reporting mechanisms within their new budget “freedoms” under LSLD. However, accountability can also be heightened in ways that do not directly relate to specific autonomy reforms, and in this article, we are more interested in the increasing (performative) accountability climate overall. Relevant here, for instance, has been the introduction of national standardised testing in Australia via the National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (or NAPLAN), with school results published online; as well as accreditation processes that require the presentation of evidence of one’s teaching against prescribed standards. Such shifts, it has been argued, can lead to teachers holding narrowly-defined performance objectives through the rise of what Wilkins et al. (2020) describe as “the neo-performative teacher”. The collection of evidence and data in proof of teaching work is something that is arguably a growing expectation of teachers today (Hardy, 2015; Talbot, 2016). Indeed, research suggests that teachers find the need to provide evidence of what they do to be a substantial component of their work, as work demands compromise their capacity to work in the best interests of their students (Stacey et al., 2022). An exploration into the perceived origins of, and changes in these work demands over time is therefore warranted.

Teacher and principal workload

Reports of increasing workload in schools have come from around Australia, with a series of union-affiliated reports across the states of Western Australia, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and New South Wales (see Gavin et al., 2022 for a synthesis of these reports). A further union-affiliated report in NSW shows that, unsurprisingly, workload increased yet further under the imposts of the 2020 COVID19 pandemic (Wilson et al., 2020). It is interesting to note this plethora of primarily union-led interest in issues of workload, which corroborates such measures as the NSW state-run “People Matters” survey which found 60% of teachers reporting unacceptable levels of work stress in 2019, very high compared to 39% for the public sector overall (NSW Public Service Commission, 2019).

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) measured change between 2013 and 2018, roughly the same period of time explored in this article. According to the most recent TALIS results, globally, teachers spent fewer total hours on “general administrative work” in 2018 than in 2013 (OECD, 2018). However, this is not true in Australia, where teachers spend an above-average amount of their time on such work, a proportion of time which did not decline but stayed about the same. Meanwhile, hours worked overall appear to have increased (Thomson & Hillman, 2019), and are above average when compared internationally (OECD, 2018). When asked about preferred priorities of government in the management of their work, it is notable that “reducing teachers’ administrative load by recruiting more support staff” was the most popular option for Australian teachers, but ranked fourth when considered across the OECD—yet still seen as “of high importance” by 55% of OECD respondents (OECD, 2019). Thus, while issues around workload are particularly prominent in Australia, they are also found elsewhere. Global reports of unmanageable teacher and principal workload beyond TALIS and the OECD are also emerging, including in New Zealand (Bridges & Searle, 2011), South Korea (Kim, 2019), the Republic of Ireland (Morgan & Craith, 2015), and the UK (Burrow et al., 2020). The research findings we report upon here are therefore likely to have resonance internationally.

A range of conceptual framings have been brought to understanding the question of teacher workload. Change to, and increase in, what teachers “do” in their day-to-day work has been argued, for instance, to lead to a need for teachers to perform “triage” in their work, leaving some activities ultimately incomplete (Stacey et al., 2022). This has meant a need to pick and choose, where possible, which work to do and not do, with work more directly connected to the classroom generally being more valued but with this decision not always an easy one to make (e.g. Ball, 2003). Workload has also been explored via the “intensification thesis” as a conceptual lens (e.g. Stone-Johnson, 2016; Fitzgerald et al., 2019). Examinations of intensification in Australian teachers’ work have a considerable history (e.g. Connell, 1985), with researchers arguing that teachers have been required to work longer and harder, subject to external pressures and without the necessary time and resources. Complementing literature on intensification, Thompson and Cook (2017, p. 29) draw on Deleuze to argue that “perceptions and experiences of time, and subjectivity itself” for teachers also require attention. Thompson and Cook explore qualitative accounts from teachers and principals explaining their experience of their work as the bounds of working time become increasingly permeable. The authors identify “two specific manifestations” of time for teachers:

First, the idea that there is not enough time to teach, which is a perception that there is more teaching to be done than is possible to do properly because of how these reforming assemblages have reconstituted what counts as “good teaching”. Second, and related to the former, is a sense of being out of time, or that the temporal rhythms that have habitually been associated with teaching as an ethical practice of disciplined care, are being reconfigured through a reinterpretation of care diffracted through testing (Thompson & Cook, 2017, pp. 33–34).

Thompson and Cook (2017), and Fitzgerald et al. (2019) are concerned mostly with how time is experienced on the ground in schools—including, in the case of Fitzgerald et al. (2019), as impacted by devolutionary structures. In this article, while we are still concerned with devolution as a key aspect of the current policy settlement, we are more concerned with reflections on the overall experience of recent policy shifts. Our conceptual framework for making this exploration is provided in the next section.

Conceptual framework: perceived change and education policy

Rosa (2003) identifies three categories of acceleration—technological acceleration, acceleration of social change, and acceleration of the pace of life. In this article, we are primarily interested in the second category, the perception “that rates of change themselves are changing” (Rosa, 2003, p. 7). A focus on “variation in the pace of change” (Fawcett, 2018, p. 549) is an aspect of social acceleration theory which, according to Fawcett, has seen comparatively less examination in the literature. It is nevertheless an important one, for “how institutions and agents perceive, interact, manage and adapt to change … has implications for the future of governance and democratic participation” (Fawcett, 2018, p. 549).

Fawcett (2018, p. 557) links subjective experiences of social acceleration as outlined by Rosa (2003) with theories of governance around “fast policy”. A primary focus within the literature on fast policy has been its spatial dimensions, for instance through diffusion and take-up of “global policy models” across and within nation states (Peck & Theodore, 2015). Yet if “ideas circulate at a much faster rate” (Fawcett, 2018, p. 557) then it follows that attempts at policy change may also be experienced as more frequent. Policy is both decontextualized and rushed, with “the need for highly visible political action … [overriding] the need for a comprehensive approach to reform” (Lewis & Hogan, 2019, p. 1). Lewis and Hogan (2019, p. 14) thereby identify a “new policy temporality” with government groups “increasingly driven by the rationale of a fast, ultra-connected polity, in which schooling reform is regularly demanded and ‘quick-fix’ solutions are putatively needed”. Thus, while in Fawcett’s (2018) view, both “fast” and “slow” approaches to politics have their time and place, perhaps a more common argument within critical education policy literature has been that fast policymaking is unhelpful and inappropriate in the context of education (e.g. Lewis & Hogan, 2019), being antithetical to careful consideration and thought. Related themes have been taken up by Rizvi and Lingard (2010, p. 20), for whom educational policy and educational change have almost become synonymous. This does not necessarily mean that “real” change or reform is indeed achieved, however; it is arguably “a problem with the current time of education policy-making … that it brings about change without producing real difference” (Thompson & Cook, 2014, p. 712). It is change for the sake of change; change as an achievement or policy “move” in and of itself.

An increased pace of change via “fast policymaking” may take the form of what has been described as “policy layering”. According to Howlett et al. (2018, p. 137), “layering is a process whereby new goals and instruments are simply added to an existing regime without abandoning previous ones, typically leading to both incoherence amongst the goals and inconsistency with respect to instruments used”. Policy design rarely begins “de novo” (Howlett et al., 2018, p. 139), after all. Pinto (2015, p. 143) explores the phenomenon of “policy layering” in Ontario, there described as “assemblages of related or unrelated policy that directs practice in schools”. Over time, layers accumulate, with educators left responsible for simultaneously enacting multiple policies. Capano notes, however, that layering is not necessarily always about change; instead, layering can also be thought of as “a mode of designing institutions through which policy-makers intervene additively with the existing institutional arrangements to affect related behaviours to achieve specific, desired results” (Capano, 2019, p. 594). Seeing layering as design may, however, also be somewhat optimistic. As Ball et al. note, policy in schools may be “reviewed and revised as well as sometimes dispensed with or simply just forgotten” (Ball et al., 2012, p. 4), subsumed within the layers. Indeed, layering is directly relevant to workload, given the sense of accumulation and “adding to” that it conveys. While workload is not a simple equation of additional tasks necessarily equalling additional time in the same way for everyone, for the school leaders in Pinto’s (2015, p. 145) ethnographic study of policy layering, “all expressed that the volume of policies was overwhelming”. As Ball et al., (2012, p. 9) put it, in such a climate:

[s]chools and teachers are expected to be familiar with, and able to enact, multiple (and sometimes contradictory) policies that are planned for them by others and they are held accountable for this task. However…individual policies and policy makers do not normally take account of the complexity of institutional policy enactment environments. It is simply assumed that schools can and will respond, and respond quickly, to multiple policy demands and other expectations. Policy is easy, enactments are not.

Indeed, Rizvi and Lingard (2010, p. 19) note that intended and unintended consequences arise from policy, and escalating workload may be one of the latter. For instance both Pinto (2015) and Ball et al. (2012) argue that the effect, if not the intention, of such heightened policy imposition can be to stifle opposition, as those on the receiving end are too busy implementing policy to resist it. Shergold (2015), in reviewing Australian government processes, recommended that policy advice should envisage and set out potential unforeseen and unintended consequences, building implementation plans into policy design to minimise unintended consequences.

In making this exploration of teachers’ reflections on policy change, we bring together ideas about social acceleration as a subjective theory regarding how time is perceived and experienced, with literature concerned with theories of governance, such as “fast policy” and “policy layering”. The link between the experiences of teachers and what is decided by education policy-makers can be understood by drawing on scholarship around policy technologies and policy enactment. Ball (2003) has argued that policy change can impact how teachers understand themselves and what it means to be a teacher. Regarding experiences of being subject to education policy in England at the turn of the 21st Century, Ball (2003, p. 220) writes:

There is a flow of changing demands, expectations and indicators that makes one continually accountable and constantly recorded. We become ontologically insecure: unsure whether we are doing enough, doing the right thing, doing as much as others, or as well as others, constantly looking to improve, to be better, to be excellent. And yet it is not always very clear what is expected.

These uncertainties, Ball argues, are largely internalised, giving rise to self-doubt and personal anxiety, and there is thus “an emotional status dimension” (p. 221) to teachers’ response to policy change. More recent work of Ball (2012, p. 625) and colleagues highlights the ways in which teachers do not simply receive but enact policy; they are “positioned differently and take up different positions in relation to policy”. Modes of governance are thereby connected in complex and varied ways with the experiences and perspectives of the subjects of that governance. This relationship may be particularly evident when we consider Rosa’s (2003, p. 26) concept of “desynchronization”, where “not all subsystems are equally capable of acceleration”, and rifts can form across different parts of the system. From this perspective, it is possible that changes introduced at state and national government levels, may not be felt to match the “pace” or capacity for acceleration at local levels. As Rosa (2015, p. 17) writes, there is a danger of “arrhythmia”, a sense of being out of step with time or feeling as though one is in the “wrong time”, perhaps with values belonging to previous iterations of public education, resonating with the “values schizophrenia” identified by Ball (2003). This may go some way to understanding teachers’ communication of policy “burnout” or fatigue, as has also been discerned elsewhere (such as in Ireland—Morgan & Craith, 2015).

To summarise, in this article we understand the relationship between the key concepts introduced above, of social acceleration, fast policy and policy layering, as follows. We propose that an experience of social acceleration is evident through a perception of increased rates of policy change, with this “fast policy” often taking the form of policy “layering”, and with particular implications for workload, as we outline above.

Within this conceptual framework, the questions we aim to address in this paper are:

-

1.

How do teachers reflect on changes to their work over the period 2013–2017?

-

2.

How do teachers reflect on the role of policy in relation to these changes?

From our research findings below, we argue that the considerable sweep of recent reforms is understood by respondents as related to an increased rate of change within an “accelerated” and “accelerating” society, through multiple, sometimes constant and sometimes contradictory or conflicting policy “layers”.

Methods

In this section, we present the methods used for gathering and analysing the survey questionnaire data upon which our arguments draw. Conducted in 2018 with full institutional ethical approval, the survey questionnaire was commissioned by the teachers’ union for public schools in NSW, the NSW Teachers Federation (NSWTF). The survey was devised by the research team and distributed by the NSWTF to their membersFootnote 2 along with information about the study to ensure informed participation, following which the team conducted independent analysis of the results. Garnering responses from 18,234 out of all 54,202 members of the union (a response rate of 33.6%), the data source can be considered quite comprehensive. This is additionally so given the high membership rate of the union, representing over 80% of the state’s public-school teachers (NSWTF, 2017). The questionnaire as a whole was designed to explore: (a) the teaching, learning and other activities currently undertaken in schools; (b) how these different kinds of work were evaluated by teachers; (c) how work (nature and quantum) was perceived to have changed over the past five years; (d) the effects of these changes; and (e) actions or strategies that might be taken to support work in schools. The data reported below relate to teachers’ retrospective perceptions of policy change over the immediately preceding period and their reflections on possible drivers of change, collected through a single-wave survey, rather than a longitudinal measure of change between two time-points.

In this paper we investigate in depth aspects of the survey that included reference to the role of state and federal policy initiatives, and teachers’ experiences of these changes.Footnote 3 While survey items make mention of particular forms of policy requirements, such as administrative work or new syllabus documents, specific policies are not engaged with. As noted by Ball et al. (2012), policy research frequently focuses on singular policy texts or suites, which can elide the complexity of the overall policy-suite. The items we report on were instead intended to gather a broad, rather than especially specific, view of current policy-related work in schools. As such, we primarily report on part “c”, and some aspects of parts “a”, “d” and “e” of the survey as outlined above, to document teachers’ retrospectively reported changes in workload over the previous five years, and their reflections which, we found, attribute this to largely administrative, policy-driven requirements.

Data relevant to answering these inquiry questions include quantitative items across the survey, as well as two specific open-ended questions directed at all respondents: the first (n = 8575) requesting that participants “comment on any changes to your workload over the last 5 years (2013–2017)”; and the second (n = 5427) to “provide any other ideas you think would support you in your work”. Given the large numbers who responded to these questions, thematic analysis of a random sample of responses was an appropriate approach. Random samples of 300 respondents were generated for each open-ended question. The samples were checked and confirmed as having representative proportions of comments and the full dataset was scanned alongside the samples to determine that the nature of comments in the samples were indicative of the full qualitative dataset. The samples were then analysed inductively to produce key themes (Ezzy, 2003). Each question was initially coded by one member of the research team, with researchers then meeting to discuss and share the codes derived. This process enabled us to identify and cross-check themes which featured consistently across questions (common codes here included, e.g. ‘administration’ and ‘accountability’), whilst maintaining the integrity of the analysis process for each particular question (e.g., the question on change over time featured commentary on ‘new responsibilities’ and (reductions or a lack of change in) ‘support’, while the question on strategies to manage workload featured commentary on a need for ‘resources’ and ‘trust, respect, esteem for the profession’). Qualitative data were understood as complementary to the quantitative data gathered, functioning as a space for participants to confirm and extend their quantitative reports. All data were rendered anonymous at the point of collection. Qualitative data are reported with a numerical identifier of that record. Quantitative data are reported using the findings from descriptive statistical analysis produced in SPSS.

The sample included a range of: levels of school (primary and secondary), socioeconomic/educational family status, locations (metropolitan, regional and remote), teaching and learning roles (all tertiary-qualified teachers, and school leaders), experience levels (early-, mid- and late-career stage), employment types (permanent, fixed-term/temporary, ‘casual’Footnote 4) and employment fraction (full-time, part-time). Whilst the effects of temporary employment have been discerned from this dataset (McGrath-Champ et al., 2022a), generally the phenomena examined in this article are understood to not be highly differentiated across these sample parameters. In the presentation of results below, we refer to “respondents” as the entirety of the respondent group, with specific roles such as “teachers” or “principals” only identified where data has been thus disaggregated.

Findings

In this section, we first provide data concerning the changing demands teachers reported alongside their perceptions of changes in support. Second, we provide data on the sources to which teachers attribute workload changes, derived from both direct statements about workload as well as in respondents’ election of strategies for managing workload. We incorporate both quantitative and qualitative data across the sections that follow.

Changing demands and support for teachers’ work

Teachers’ working hours are considerable, with classroom teachers reporting an average of 55 h per week during term (Gavin et al., 2022), and principals/deputy principals an average of 62 h. Respondents to the survey also note that this overall quantum of hours is somewhat new. Respondents were asked to report changes to their work over the past five years (from 2013 to 2017), identifying a significant growth in overall hours, with 87% reporting an increase over this period, as well as increases in: complexity (95%); range of activities (85%); the collection, analysis and reporting of data (96%); and administrative tasks (97%). Here it is relevant to note that vast numbers of classroom teachers remain in the same role for longer than five years and a length of experience does not automatically entail increased responsibility. While it is possible that career progression may mean, over five years, some respondents take on more senior roles, this is through a teacher specifically seeking a “promotions position”. Career advancement may involve new tasks and greater complexity for a worker, however, effective labour market “matching” between jobs and suitable candidates means this does not necessarily entail enduring increase in workload. “Progression” alone is very unlikely to account for the reported workload increases.

Indeed, respondents report work related to central policy requirements as constituting a significant portion of their overall work—not so much that it is done daily, but every week or at a frequency that is less than weekly. For instance, in the section of the survey where respondents marked off frequency of activities undertaken from a provided list, “working on accreditation-related requirements” is reported as being in the top ten activities undertaken every week. Respondents also identify the following activities as being in the top ten work activities done less frequently than weekly (such as fortnightly or more intermittently than weekly):

-

Reporting of student attainment information to external authorities,

-

Work associated with the School Excellence Framework, including self-assessment and external validation,

-

Responding to and dealing with NESA [state regulatory authority] requirements in relation to curriculum, accreditation and inspections,

-

Providing evidence of implementing NSW departmental policies and procedures, and

-

Data collection analysis and reporting associated with state-wide strategies.

Interestingly, all of these policy-related activities were negatively evaluated by respondents as being unimportant/unnecessary, not needing more time and resources, being time-consuming and cumbersome, and/or focused on compliance rather than teaching and learning.

In tandem with the increases in this work undertaken by respondents are their reports of reduced support. Head teachers, principals and assistant principals were the groups most likely to report decreases in the level of support received from the NSW Department of Education. The response patterns in relation to Departmental support are reported, in full, in Table 1. Here the pattern shows staff are split between reporting no change or a decrease in support. Very low proportions (between 8 and 12%) report that departmental support has increased.

The most dominant theme in responses to the open-ended question (“comment on any changes to your work over the past 5 years (2013–2017)”), focused on administrative requirements. Respondents described the increase in these demands, with one stating that “administrative tasks and record keeping has more than doubled in the past 5 years” (#6734085759). In focus here is the changing nature of work as well as its increase in quantity, with frequent references to “paperwork”: “there is way too much paperwork” (#6782272421); “the amount of paperwork required is ridiculous” (#6733036573). “Admin” was often linked by respondents to accountability mechanisms, identifying an “increase in irrelevant administration related to teacher accountability” (#6707701557) with “the greatest change” being “the amount and importance of … box-ticking style evaluation and oversight processes” (#6704995007) with “accountability in programming and collection of data” becoming “extreme” (#6721509510). “Admin” is considered as a theme distinct from other potential accountability mechanisms, for example concerns about “executive observation” leading to a sense of “feeling watched” and “feeling criticised” (#6763815151).

Another common theme expressed a lack, or reduction, of central supports. While respondents reported that demands have increased, consistent with the quantitative findings, qualitative accounts also articulated that the level of support they were receiving either had not changed, or had decreased. About half of all qualitative comments that addressed the issue of support suggested that it had decreased. One respondent recalled that they “used to have a team of people in district/regional office who we knew by name and provided great support for schools” but that this “appears to have disappeared” (#6757602772). Other respondents simply noted that what was available was felt to be unhelpful or inadequate (“many more policies and rule requirements … most support [was] simply … more information thrown at us” (#6720603224)), while some noted that supports had only stayed the same despite increasing demands: “the demands on staff have increased yet we've not had increased support to assist us” (#6708395150); there is “more paperwork, preparation, higher expectations [but] less and less time given [and] we’re just expected to magically make it happen” (#6750183523)—“more is expected with a ‘suck it up or move on’ attitude” (#6721562094). This situation is summarised by a respondent as one where “society and education administrators are trying to make education work under a business model” (#6718535272). Another commented that there seems to be “no time to consolidate and apply new knowledge before a new “improved” version is introduced and proficiency demanded!” (#6733794660).

Both the quantitative and qualitative findings provide clear evidence that teachers have experienced an increase in workload, alongside diminished support towards accomplishing what is asked of them. How teachers attribute this increase in work demands is the focus of the next section.

Teacher attributions of workload change and workload management strategies

Respondents directly attribute workload change to government initiatives. This is evident, for instance, in items that queried which elements of work might hinder teaching and learning. A very large majority of respondents reported (agree/strongly agree) teaching and learning to be hindered by their high workload (89%), having to provide evidence of compliance with policy requirements (86%), and new administrative demands introduced by the Department (91%) (see Table 2).

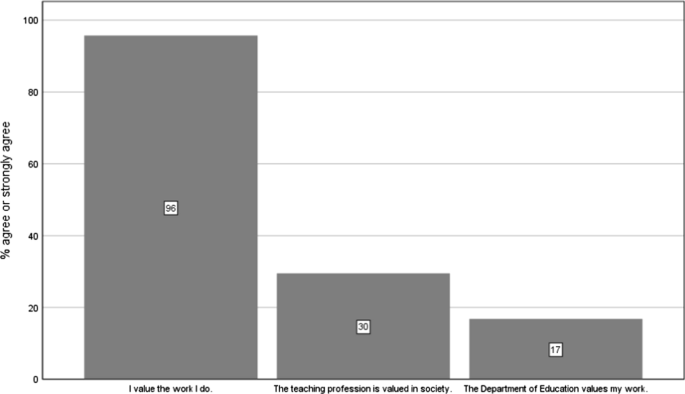

We note the overlap in these items: administrative demands (3) and compliance with policy (2) clearly, in the view of these respondents at least, form part of workload overall (1)—as the findings presented in the previous section indicate. Conflicting demands of administrative and paperwork work, versus teaching and learning work, was reported most strongly by classroom and specialist teachers (91%) and head teachers and assistant principals (92%). Pertinent to this finding of conflict between system and classroom demands are two further questions asked in the survey: whether respondents feel their work is valued by the education department on the one hand, and by society at large on the other. Only 17% of classroom teachers (strongly/) agreed that “the Department of Education values my work”, with a very large 44% (strongly/) disagreeing, and 40% selecting “neutral”. This pattern of responses was similar for other roles (principals, specialist teachers, teaching consultants). This distinctly contrasts with reports of how society values teachers’ work, with 30% of classroom teachers (strongly/) agreeing that “the teaching profession is valued in society”, where 46% (strongly/) disagreed, and 25% were “neutral” (see Fig. 1).Footnote 5

The attribution of workload change to centralised policy initiatives is further evidenced by respondents’ ranking of strategies that may help to manage workload in the future (Table 3). Most of the eleven pre-identified strategies focus on areas of additional system support. The top-ranked strategy focusses on reduction in face-to-face teaching time in order to increase time available for collaboration with colleagues. This strategy sits comfortably with the third highest, namely, providing more specialist teacher support for students with special needs. Both these strategies focus on additional relief/support to strengthen teaching and learning. These contrast with the remaining top-five ranked strategies, which variously reflect teachers’ desires for: elimination of unnecessary and cumbersome processes; more effective system-level planning to avoid imposing more demands; and ensuring consultation prior to any significant reform or initiative. The high ranking of these strategies by large numbers of NSW teachers suggests their collective analysis of the problem of workload increase has focused, not just on the challenges within their schools, but on the system frameworks that schools and teachers sit within. However, we also note that some strategies relating to “admin” support, via the hiring of additional staff, were lowly ranked and did not make it into the top five. That such strategies were ranked lower may indicate that respondents perceive the problem to be the requirements themselves more than who is being asked to complete them.

We also analysed qualitative data from the second open-ended question in the survey asking participants to expand on suggested “actions or strategies that might be taken to support work in schools”. Unlike the ranking activity, this question allowed respondents to describe any strategy they thought important or to clarify their response to the ranking list. Here we note—amongst calls for the general reduction of administrative work and increase of supports—a prevalence of commentary directly focused on policy initiatives, including those coming from the NSW Department of Education. There was an expressed need for “more resources, more support staff, better implementation of systems—stop rushing to roll out initiatives that are not thought out and tested” (#6720525953). There was similarly a view that the Department “should stop changing things all the time. See how a change impacts before changing again” (#6748477500). Authorities should “choose one or two new initiatives, rather than several, for schools to implement at any time and allow teachers to become proficient in these before bringing in further initiatives” (#6749841177). Finally, one respondent stated a desire for “trust” that “teachers are capable of thinking for themselves and making complex decisions without the extraordinary layers of bureaucracy and political interference” (#6710718550). This complemented a more generally expressed sentiment across the open responses in the survey that there should be, as one respondent put it, “less paperwork to cover someone else’s butt further up the food chain” (#6734171350).

To summarise, our findings suggest a perception of overall increase in work demands alongside reduced support. Teacher respondents attribute these workload increases to state and federal policy and associated institutions. In the next section, we discuss these findings in light of existing research and our conceptual framework.

Discussion

Almost universally, respondents in this study perceived a change in workload, with a distinct increase over the five-year period from 2013 to 2017. This echoes concerns raised in research on teachers’ work and workload around Australia, and around the globe (OECD, 2019; Stone-Johnson, 2016; Thomson & Hillman, 2019). While TALIS data indicate that teachers’ overall working hours have increased, and that Australian teachers complete an above-average amount of administrative work, what the data presented in this article convey is that in NSW, specifically administrative work is also perceived to have increased. This coheres with literature on “datafication” in and of teaching (e.g. Hardy, 2015) and which map new requirements for documentation and “proving” of work, for instance through accreditation processes (Talbot, 2016). While change is not a bad thing, and nor is being accountable, these shifts could be questioned if they are impinging, as our data show, on key tasks within a teacher’s workday without a clear benefit. In this way, our findings connect with literature on both teacher workload, as well as datafication and accountability.

The data analysed here also speak to literature on autonomy and devolution, which as noted earlier, often works in tandem with heightened accountability. The evidence presented above indicates a perception among teachers that support provided by the Department for managing new initiatives has been reduced or is otherwise inadequate. The loss of “mid-level” supports, noted particularly in qualitative responses, reflects autonomy models elsewhere, such as in England (Ball, 1990), and corroborates previous findings on the impact of devolution in Australia (Fitzgerald et al., 2018). It is therefore noteworthy that the questions in our survey asked respondents to consider how their work had changed over the past five years, a period of time that maps on to the introduction of major reforms in NSW, including the LSLD initiative which sought to devolve greater responsibility for financial decisions and staffing to school principals. In the data we have presented, changes in workload were explicitly attributed to the introduction of new policies and initiatives during this period. The irony of this attribution in the context of a policy suite purportedly intended to “free up” the work of local actors in a political environment where “efficiency has become a kind of metavalue” (Rizvi & Lingard, 2010, p. 116), is stark. Indeed, as Crawford (2020) notes, the aim of LSLD to “reduce red tape” (one out of five goals of the policy) is one area which clearly has not been met (CESE, 2020). The failure of the LSLD policy led to its partial unwinding from 2021, including a gesture by the Departmental employer via a new “Quality Time Program” (NSW Government, 2022a) to free up a small quantum of teachers’ “low-value” administrative time, and with additional time for the initial implementation phase of a new curriculum announced in October 2022 (NSW Government, 2022b). Simultaneously, the NSW government has been asserting greater influence over curriculum, with lesson planning described by the Department as a “tax” on teachers’ time (NSW Government, 2022c). Yet in our large data set teachers report this to be a core and deeply valued element of their work (Stacey et al., 2021). It appears that teachers experience the market/accountability mechanisms associated with autonomy reforms as problematic, perhaps more so than the autonomy reforms per se. Here, it is necessary to distinguish between school autonomy, principal autonomy and teacher autonomy, as reforms that have endowed school and principal autonomy have not tended to foster teacher autonomy.

Additionally, the data suggest that we may not only see in this relationship a “profound distrust” (Ball, 1990, p. 214) of teachers by the government, but conversely, deep distrust of the government by teachers. The widely-held perception by teachers that their work is not valued by their employer and the state policy-maker, the Department of Education, was noted above (Fig. 1). It is highly likely that those who do not feel valued by their employer are also not likely to trust their employer. While this could be understood as a kind of worker dissatisfaction common across industries, the higher percentage of teacher respondents (nearly double) feeling valued by broader society disrupts any such rationalisation, and suggests a considerable disjuncture between employer and employee. It has long been understood that trust in the workplace is vital to good workplace performance, productivity and favourable working relations; and a dimension to which there has been much attention, not only in literature and theory, but also practice (Isaeva et al., 2019).

We acknowledge that the data we have presented in this article are retrospective and self-reported. While they are corroborated by a range of other data sources reflecting increases in amount and nature of work, our findings cannot necessarily be taken as “fact” and further research that tracks workload longitudinally, in addition to that documented by TALIS (OECD, 2019), would be beneficial. Similarly, the question of whether there have “objectively” been more policy changes during this time, or not, is not one this article can provide a definitive answer to, and again, could be a meritorious focus of further study. It is also true that, to some extent, most people would probably describe themselves as increasingly “busy” and as hard workers, within the teaching profession and beyond. This is, however, where our conceptual framework is of utility. Teachers’ perception of workload increase resonates with experiences of an increasing pace of change in modernity (Rosa, 2003). The “truth” of this proposition seems, at the least, to be perceived by teachers, with “policy” becoming synonymous with change (Rizvi & Lingard, 2010). However, this change is not necessarily “in time” with teachers themselves, conveying a disjuncture between what is being asked for, and what can be delivered, as demands are layered on top of one another. The data thereby also align with theories of governance that identify moves towards “fast policy” processes and policy “layering”. “Fast policy” is likely exacerbated through the delivery of publicly consumable “new policy” messages conveyed by news media which usually has remarkably short “newsworthiness”, and in Australia, is also fuelled by political (re-/)election cycles. Indeed, we note that the government’s recent efforts at addressing teacher time use, particularly in relation to curriculum implementation and lesson planning (NSW Government, 2022b, 2022c), have emerged mere months before a state election is due. Additionally, the findings are consistent with other measures, including international (Thomson & Hillman, 2019) and Australian government (NSW Public Service Commission, 2019) surveys which report increasing work demands and hours. This suggests that these “perceptions” are at least felt, and also reported, consistently from an array of external sources. As the OECD (2019) study documents the issue of administrative load on teachers in numerous countries, insights from our study in Australia may inform research and practice in other locations.

Fawcett (2018) argues that there is a time and place for “fast” policy, for instance in crisis contexts. However, absent such crisis, we would argue in support for Saward’s call for “formal moments of delay” (2017, p. 374) to support “slow democracy”, as a part of how policy can be effectively designed so that “collective decisions are reached” (2017, p. 373). While the data presented above suggest ample resistance on the part of teachers to responsibilising policy shifts, with teachers calling upon the government to increase support and reduce demands in their work, it is worth noting that both Ball et al. (2012) in the UK and Pinto (2015) in Canada have identified the tendency for policy imposition on teachers to stifle resistance through work overload. In this way, teachers’ expression of “reform fatigue” in the data we present arguably constitutes “a form of resistance by those having to implement top-down policy”, even though it may be seen as a “form of intransigence by those wanting the policy implemented” (Rizvi & Lingard, 2010, pp. 20–21). Yet as Ball et al., (2012, pp. 138–139) state of their data:

what we might call resistance, a full-blown reflexively articulated confrontation between agonistic discourses, is rare and fleeting – limited for example to moments of political or trade union action. In the mundane, in relation to the pressures of performance, in response to constant change, there is little space or time or opportunity to think differently or “against”.

Reinforcing the stifling effects of work overload has been the general shift from more militant union strategies of “resistance” to strategies of rapprochement and renewal. While teacher unions may not necessarily embrace the neoliberal logic of policy reform, they commonly do not attempt to overtly confront or challenge it (Gavin, 2019). Our survey constitutes an exception: providing opportunity for “voice” (Wilkinson & Barry, 2016) in relation to workload was an articulated NSWTF aim (McGrath-Champ et al., 2022b). Though completing the survey momentarily—and ironically—added to teachers’ “work”, it constituted a conduit for expression of concern and resistance, evident in the nature and extent of responses and the overwhelmingly large completion-rate. Scheduled deliberately just after the start of the school year, when workload is slightly less than at many other times, teachers embraced this research, and the indication of consequent union-action, as a ready-instrument for “voice” over adverse workload and policy effects. More recently, we note that discontent with workload escalation, stalled salary renegotiations and dire staff shortages have sparked “antagonistic discourse” (Ball, 2012) via brief but repeated industrial strikes in 2021–2022 (NSWTF & IEU, 2022). This then escalated to a nation-wide ministerial summit convened by the newly-elected centre/left-wing national government with intention to devise an “action plan” on teacher shortages (Worthington, 2022). While a policy response to issues raised by the profession is welcomed, this may impel yet more “layering” and “fast policy”. We note, for example, the controversial intention to provide “lesson plans” for teachers in NSW as a means to address workload (NSW Government, 2022c), a move which contradicts the “strategies” teachers call for in this article, and which may therefore be more “fast policy”.

We also note that social acceleration is “not a steady process but evolves in waves … with each new wave meeting considerable resistance as well as partial reversals”. With each wave, “cries for deceleration in the name of human needs and values are voiced but eventually die down” (Rosa, 2003, p. 3). As such, while desynchronization may result in some moments of pause, as perhaps reflected in the use respondents made of this survey to air their concerns, these are temporary. As Rosa (2015, p. 117) writes:

As in an earthquake, not all layers (of the ground) shift at the same pace … the various realms of society move at different speeds, and individual oases of deceleration repeatedly form that, like stable rock ledges in an earthquake, promise a limited stability in rapidly changing surroundings.

It is, therefore, important to give ongoing attention to the current historical and political moment of neoliberalised education policy reform, as well as how this settlement may be shifting.

Conclusion

With a less than certain destination, politics in modernity, argues Rosa (2003, pp. 23–24), “loses its sense of direction” and “shifts to ‘muddling through’ … with increasingly temporary and provisional solutions”. In the case of NSW and its public-school teachers, such “solutions” are sometimes, but not necessarily always, temporary with many simply being added on top of one another, creating a “layering” effect. For Rosa, part of the dynamic when politics “loses its sense of direction” in this way, is to shift responsibility for decision-making elsewhere, including to the level of the individual. Policy-making in an age of acceleration is therefore tied to questions of decentralisation, accountability and responsibility; this resonates strongly with teachers’ perceptions of the shifts in their workload in NSW over the 5 years 2013 to 2017. Teacher respondents in this study attributed their workload increases primarily to new government initiatives requiring additional paperwork and administrative efforts. Given the prevalence of autonomy models of schooling today, especially in England and the United States (Keddie, 2017) but also elsewhere around the globe, these findings may also have significance beyond Australia.

Bringing together the theory of social acceleration and literature on theories of governance in education, such as autonomy reform and policy “layering”, is a key contribution of this article that is further enhanced through attention to recent empirical reports of workload increase. It is our view that working across these literatures enables a more detailed picture to emerge of how reform can be perceived and experienced. It also suggests a need for more attention to the temporal dimensions (and consequences) of both global and local “fast policy”. Indeed we note that, as with studies of acceleration more generally, studies of education policy do not often consider stakeholders’ perceptions of change over time, an area ripe for further research. Yet for the teachers in our study, it would seem that the very idea of “policy” is becoming synonymous with “change”. We argue that acceleration of the pace of change, as an experiential condition, is reflected in teachers’ reports of a growing workload and attribution of this to policy change, an assessment which we have argued has some resonance with the identification of “fast policy” and policy “layering” as modes of education governance. This article makes a theoretical contribution to conceptualisations of policy development and change by linking these modes with subjective experiences of acceleration, speaking across a number of debates within the broader literature around education governance, rationalist approaches to policy development, individual subjectivity, and policy enactment “on the ground”.

Our analysis indicates some cause for concern, bringing the effects of “fast policy” processes into question. Regardless of whether or not it is objectively “true” that we are indeed seeing more frequent and numerous changes over shorter periods of time, teachers’ perceptions of this are important in their own right. While literature has argued that neoliberal reform reflects a lack of trust in teachers for many years (e.g. Ball, 1990), what our findings indicate is that the reciprocal may also be true: teachers perceive that they are not valued by their government employer and it is logical that teachers reciprocate with lack of trust in government. This sense of a rift between teachers and government may also reflect some resistance among teachers in an age of competition and performativity; and may, in the long term be able to stir positive change in how policy is developed. Building on Saward (2017) and Shergold (2015), we argue for moves towards “slow democracy” in education, with consultation not only with key government groups but with teachers themselves, through a shift toward respectful and supportive—rather than onerous and responsibilising—governance structures.

Notes

In Australia, school education is a residual power of the states and territories. As such, it is the states which have primary responsibility over the funding of public schools.

To ensure confidentiality of member contact information.

Broad overall results of the questionnaire were reported to the Union (McGrath-Champ et al., 2018).

In 'casual’ work, a teacher is employed on a day-to-day basis to meet relief needs within the school. In some contexts, this is referred to as ‘substitute’ (USA) or ‘supply’ (UK).

These data are pre-COVID-19 and the home schooling necessitated by the pandemic provided a closer parental ‘window’ onto teachers’ work though the longer-term effects of this on the valuing of teachers’ work is unclear.

References

Ball, S. J. (1990). Politics and policy making in education: Explorations in policy sociology. Routledge.

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. Routledge.

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teachers soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228.

Bridges, S., & Searle, A. (2011). Changing workloads of primary school teachers: “I seem to live on the edge of chaos.” School Leadership and Management, 31(5), 313–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2011.614943

Burrow, R., Williams, R., & Thomas, D. (2020). Stressed, depressed and exhausted: Six years as a teacher in UK state education. Work, Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020903040

Capano, G. (2019). Reconceptualizing layering - from mode of institutional change to mode of institutional design: Types and outputs. Public Administration, 97, 590–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12583

Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE) (2020). Local schools, local decisions evaluation final report. NSW Department of Education. Retrieved from cese.nsw.gov.au.

Chitty, C. (2013). New Labour and secondary education, 1994–2010. Palgrave Macmillan.

Connell, R. (1985). Teachers’ work. George Allen and Unwin.

Connell, R. (2013). The neoliberal cascade and education: An essay on the market agenda and its consequences. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2013.776990

Crawford, M. (2020). Local schools, local decisions: Needs-based equity funding. Audit Office of New South Wales.

Ezzy, D. (2003). Qualitative analysis. Taylor and Francis.

Fawcett, P. (2018). Doing democracy and governance in the fast lane? Towards a “politics of time” in an accelerated polity. Australian Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 548–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2018.1517862

Fitzgerald, S., Stacey, M., McGrath-Champ, S., Parding, K., & Rainnie, A. (2018). Devolution, market dynamics and the Independent Public School initiative in Western Australia: ‘Winning back’ what has been lost? Journal of Education Policy, 33(5), 662–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1412502

Fitzgerald, S., McGrath-Champ, S., Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & Gavin, M. (2019). Intensification of teachers’ work under devolution: A ‘tsunami’ of paperwork. Journal of Industrial Relations, 65(1), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618801396

Gavin, M. (2019). Working industrially or professionally? What strategies should teacher unions use to improve teacher salaries in neoliberal times? Labour and Industry, 29(1), 19–33.

Gavin, M., McGrath-Champ, S., Wilson, R., Fitzgerald, S., & Stacey, M. (2022). Teacher workload in Australia: National reports of intensification and its threats to democracy. In S. Riddle, A. Heffernan, & D. Bright (Eds.), New perspectives on education for democracy: Creative responses to local and global challenges (pp. 110–123). Routledge.

Gobby, B., Keddie, A., & Blackmore, J. (2018). Professionalism and competing responsibilities: Moderating competitive performativity in school autonomy reform. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 50(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2017.1399864

Hardy, I. (2015). Data, numbers and accountability: The complexity, nature and effects of data use in schools. British Journal of Educational Studies, 63(4), 467–486.

Hasim, A. K., Torres, C., & Kumar, J. M. (2021). Is more autonomy better? How school actors perceive school autonomy and effectiveness in context. Journal of Educational Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09439-x

Holloway, J., & Keddie, A. (2019). Competing locals in an autonomous schooling system: The fracturing of the “social” in social justice. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 48(5), 786–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219836681

Howlett, M., Mukherjee, I., & Rayner, J. (2018). Understanding policy designs over time. In M. Howlett & I. Mukherjee (Eds.), Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 136–144). Routledge.

Isaeva, N., Hughes, C., & Saunders, N. M. K. (2019). Trust, distrust and human resources management. In K. Townsend, K. Cafferkey, A. M. McDermott, & T. Dundon (Eds.), Elgar introduction to theories of human resources and employment relations (pp. 247–263). Edward Elgar.

Keddie, A. (2017). School autonomy reform and public education in Australia: Implications for social justice. Australian Educational Researcher, 44, 373–390.

Keddie, A., Gobby, B., & Wilkins, C. (2018). School autonomy reform in Queensland: Governance, freedom and the entrepreneurial leader. School Leadership and Management, 38(4), 378–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2017.1411901

Kim, K. (2019). Teachers’ administrative workload crowding out instructional activities. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 39(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1572592

Lewis, S., & Hogan, A. (2019). Reform first and ask questions later? The implications of (fast) schooling policy and “silver bullet” solutions. Critical Studies in Education, 60(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1219961

McGrath-Champ, S., Wilson, R., Stacey, M., & Fitzgerald, S. (2018). Understanding work in schools. Surry Hills, NSW: NSW Teachers Federation. https://www.nswtf.org.au/files/18438_uwis_digital.pdf.

McGrath-Champ, S., Fitzgerald, S., Gavin, M., Stacey, M., & Wilson, R. (2022a) Labour commodification in the employment heartland: Union responses to teachers’ temporary work. Work Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211069854

McGrath-Champ, S., Gavin, M., Stacey, M., & Wilson, R. (2022b). Collaborating for policy impact: Academic-practitioner collaboration in industrial relations research. Journal of Industrial Relations, 64(5), 759–784. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856221094887

Morgan, M., & Craith, D. N. (2015). Workload, stress and resilience of primary teachers. Irish National Teachers Assocation. https://www.into.ie/app/uploads/2019/07/WorkloadReport_Sept15.pdf.

NSW DEC. (2011). Local schools, local decisions. NSW Department of Education and Communities.

NSW DEC. (2017). Early action for success. http://www.dec.nsw.gov.au/about-the-department/our-reforms/early-action-for-success.

NSW Public Service Commission. (2019). People matter. https://www.psc.nsw.gov.au/reports---data/people-matter-employee-survey/previous-surveys/people-matter-employee-survey-2019/education/education.

NSW Education Standards Authority. (2019). Retaining work samples. https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/11-12/Understanding-the-curriculum/awarding-grades/retaining-work-samples.

NSW Government. (2022a). Quality time program. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/quality-time/quality-time-program.

NSW Government. (2022b). Extra time for teachers. https://education.nsw.gov.au/news/latest-news/extra-time-for-teachers.

NSW Government. (2022c). Number one tax on teachers’ time solved. https://education.nsw.gov.au/news/latest-news/number-one-tax-on-teachers-time-solved.

NSWTF. (2017). Court action re: permanent employment for casual and temporary teachers. https://www.nswtf.org.au/files/court_action_re_permanent_employment_for_casual_and_temporary_teachers.pdf.

NSWTF & IEU. (2022). Joint media release: Public and Catholic school teachers to strike on 30 June. Avaiable at https://news.nswtf.org.au/blog/media-release/2022/06/public-and-catholic-school-teachers-strike-30-june. Accessed on 5 October 2022.

OECD. (2018). Indicator D4: How much time do teachers spend teaching? In Education at a glance 2018: OECD indicators. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2018_eag-2018-en#:~:text=Education%20at%20a%20Glance%3A%20OECD,a%20number%20of%20partner%20countries.

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (Volume 1): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. OECD Publishing.

Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2015). Fast policy: Experimental statecraft at the thresholds of neoliberalism. University of Minnesota Press.

Pinto, L. E. (2015). Fear and loathing in neoliberalism: School leader responses to policy layers. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 47(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2015.996869

Ravitch, D. (2010). The death and life of the great American school system. Basic Books.

Rizvi, F., & Lingard, B. (2010). Globalizing education policy. Routledge.

Rosa, H. (2003). Social acceleration: Ethical and political consequences of a desynchronized high-speed society. Constellations, 10(1), 3–33.

Rosa, H. (2015). Acceleration: A new theory of modernity. Columbia University Press.

Saward, M. (2017). Agency, design and “slow democracy.” Time and Society, 26(3), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X15584254

Shergold, P. (2015). Learning from failure: Why large government policy initiatives have gone so badly wrong in the past and how the chances of success in the future can be improved. Western Sydney University publishing. http://www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/learning-from-failure.

Stacey, M., Fitzgerald, S., Gavin, M., McGrath-Champ, S., & Wilson, R. (2021). Will the quality time action plan reduce teacher workload? EduResearch Matters, 23 September. https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=10768

Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & McGrath-Champ, S. (2022). Triage in teaching: The nature and impact of workload in schools, Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 42(2), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1777938.

Stone-Johnson, C. (2016). Intensification and isolation: Alienated teaching and collaborative professional relationships in the accountability context. Journal of Educational Change, 17, 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-015-9255-3

Talbot, D. (2016). Evidence for no-one: Standards, accreditation and transformed teaching work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58, 80–89.

Thompson, G., & Cook, I. (2014). Education policy-making and time. Journal of Education Policy, 29(5), 700–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.875225

Thompson, G., & Cook, I. (2017). The politics of teaching time in disciplinary and control societies. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(1), 26–37.

Thomson, S., & Hillman, K. (2019). TALIS 2018 Australian report: Volume 1: Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006andcontext=talis.

Wilkins, C., Gobby, B., & Keddie, A. (2020). The neo-performative teacher: School reform, entrepreneurialism and the pursuit of educational equity. British Journal of Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2020.1739621

Wilkinson, A., & Barry, M. (2016). Voices from across the divide: An industrial relations perspective on employee voice. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(3–4), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002216649899

Wilson, R., Stacey, M., & McGrath-Champ, S. (2020). Teachers’ work during the COVID-19 pandemic: Shifts, challenges and opportunities. Occasional Papers #169. Centre for Strategic Education. https://www.cse.edu.au/content/teachers%E2%80%99-work-during-covid-19-pandemic-shifts-challenges-and-opportunities.

Worthington, B. (2022). Education ministers are in unison on fixing the teacher shortage crisis—but is that enough for a plan to materialise? ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-13/education-ministers-jason-clare-teacher-shortage-conditions/101327776, Accessed on 5 October 2022.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results received funding from the Australian Education Union (New South Wales Teachers Federation Branch) under Contract Number CT20810. We gratefully acknowledge advice on the paper by Scott Fitzgerald, Mihajla Gavin and Greg Thompson, although the content of the paper rests with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stacey, M., McGrath-Champ, S. & Wilson, R. Teacher attributions of workload increase in public sector schools: Reflections on change and policy development. J Educ Change 24, 971–993 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-022-09476-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-022-09476-0