Abstract

Data-informed decision making is considered important for school improvement. Working in data teams is a promising strategy for implementing data use in schools. Data teams consist of teachers and school leaders, who collaboratively analyze data to solve educational problems at their school. Studies show that school leaders can enable and hinder data use in such teams. This study aims at exploring what types of leadership behaviors are applied to support data use in data teams. The results of this study point to five key building blocks for school leaders wanting to build effective data teams in their school: (1) establishing a vision, norms, and goals (e.g., discussing vision, norms, and goals with teachers); (2) providing individualized support (e.g., providing emotional support); (3) intellectual stimulation (e.g., sharing knowledge and providing autonomy); (4) creating a climate for data use (e.g., creating a safe climate focused on improvement rather than accountability, and engaging in data discussions with teachers); and (5) networking to connect different parts of the school organization (e.g., brokering knowledge and creating a network that is committed to data use). Not only formal school leaders, but also teachers, can display these types of behavior. Finally, it is important to stress here that all these building blocks are needed to create sustainable data use practices. These building blocks can be used in a new wave of data-informed decision making in schools, in which teachers and school leaders collaboratively use a multitude of different data sources to improve education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Data use leads to educators concentrating more on students’ deficits than their assets. Data use focuses only on standardized assessment and achievement on a narrow set of topics (e.g., literacy and numeracy). Data use leads to too much pressure on teachers. An emphasis on data use leads to cheating on tests and teaching to the test (Booher-Jennings 2005; Hargreaves et al. 2018). These statements against the use of data have been made a lot in the past decade, and reflect what we would like to call the old wave of data use or data-based decision making (also referred to as data-driven decision making).

However, we are seeing a new wave of data use arising, which we would like to call data-informed decision making, in which data can never completely drive decisions. Instead data can inform decisions, which, combined with the professional knowledge of educators, can contribute to achievement and learning in schools. This type of data use does not focus solely on achievement on a narrow set of topics, but can be used to work on different sets of goals (e.g., literacy and numeracy, but also well-being, arts, critical thinking, and creativity, see Hargreaves et al. 2018). Moreover, data use does not include only standardized assessment data, but includes any type of data that can provide information on the functioning of schools, such as classroom assessment data, classroom observations, student focus groups, and so forth. Data can then be defined as any information that is systematically “collected and organized to represent some aspect of schools” (Lai and Schildkamp 2013, p. 10). This new wave of data use is studied in many countries around the world, such as Belgium (e.g., Van Gasse et al. 2016; Vanhoof et al. 2012; Vanlommel et al. 2016), Canada (e.g., Earl and Katz 2006; Katz and Dack 2014), New Zealand (e.g., McNaughton et al. 2012; Lai et al. 2014), Norway (e.g., Mausethagen et al. 2018; Prøitz et al. 2017), Germany (e.g., Demski and Racherbäumer 2017), Sweden (e.g., Blossing et al. 2018), England (e.g., Downey and Kelly 2013; Schildkamp et al. 2014), South Africa (e.g., Archer et al. 2013), Trinidad and Tobago (e.g., De Lisle 2015; De Lisle et al. 2013), the US (e.g., Datnow and Park 2018; Mandinach and Gummer 2013), and the Netherlands (e.g., Schildkamp and Poortman 2015; Van der Scheer and Visscher 2016; Van Geel et al. 2016).

Research supports the importance of using meaningful and accurate data in schools in order to make informed decisions (e.g., Lachat and Smith 2005; Schildkamp and Kuiper 2010; Wayman and Stringfield 2006; Wohlstetter et al. 2008). Based on data, school leaders and teachers can assess to what extent changes are needed in the school and classrooms, and they can implement these educational changes accordingly. Emerging evidence from the US (Carlson et al. 2011), New Zealand (Lai et al. 2014) and the Netherlands (Poortman and Schildkamp 2016; Van Geel et al. 2016), suggests that under the right conditions, data use can lead to school improvement in terms of higher student achievement.

However, researchers frequently report that schools struggle with implementing data use effectively (Mandinach and Gummer 2013; Marsh 2012), principally because educators lack the required knowledge and skills (e.g., Marsh 2012). A promising strategy for supporting the implementation of data use in schools is professional development for teachers and school leaders related to data use in teams (Earl and Katz 2006; Wayman and Stringfield 2006). It is also important to take into account the role of the school leader. Studies show that school leaders can both enable and hinder the use of data in teams (e.g., Park and Datnow 2009; Schildkamp and Poortman 2015; Wayman et al. 2012). School leaders occupy key positions in schools as far as, for example, implementing a culture of data use (Sutherland 2004; Vanhoof et al. 2012). However, school leaders can also hinder data use, for example by not facilitating teachers in time to meet, and by using data to “blame and shame” teachers instead of focusing on how to collaboratively use data to improve education (Datnow and Hubbard 2015). Moreover, although we know from previous research that the role of the school leader is crucial in implementing interventions, it is not known how to apply these leadership behaviors in professional development interventions focused on data use. Therefore, this paper focuses on the role of school leaders in a data team intervention.

Theoretical framework

Data use professional development interventions

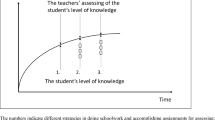

Large-scale teacher professional development interventions for data use have been implemented in diverse contexts over the last few years (e.g., Carlson et al. 2011; Lai et al. 2014; Poortman and Schildkamp 2016). In this study we focus on a data team professional development intervention. These data teams (Lai and Schildkamp 2013) follow an iterative and structured approach (see Fig. 1). It involves following eight steps in order to collaboratively solve educational problems in schools. These eight steps form the basis of the data team intervention. The goal of the data team intervention is to scaffold data teams in the effective use of data for making informed decisions and solving educational problems. In this way, data teams can be an avenue for professional development, with the ultimate goal of school improvement. Results of studies in Dutch secondary education indicated that the data team intervention supports schools in implementing data use and in solving educational problems (Poortman and Schildkamp 2016).

The eight steps of the data team intervention (Lai and Schildkamp 2013, pp. 56–57)

In this study, data teams consisted of three to six teachers, and one or two school leaders (and an internal data expert, if available). Data teams met every 3–4 weeks for 90 min in order to solve an urgent problem within their own school (e.g., low mathematics achievement, problems concerning transitions between grades). The data teams received support from an external data coach over a 2-year period (for more information see the method section).

Transformational leadership

In this paper, we argue that transformational leadership is important for building effective data teams. Transformational leadership in educational settings can be operationalized as a construct comprised of three building blocks: (1) initiating and identifying a vision, (2) providing individualized support, and (3) providing intellectual stimulation (Geijsel et al. 2009, 2003; Leithwood and Jantzi 2006).

The data team intervention aims at challenging the status quo in schools and wants to encourage greater data use for making informed decisions in schools. One characteristic of the data team intervention in this study is that school leaders participate during the meetings. Literature is scarce about the role of school leaders when participating with teachers in teams, such as data teams. However, in the past decades, studies have pointed to the importance of transformational leadership when implementing educational innovations in schools in a variety of international settings (e.g., Geijsel et al. 2003, 2009; Hallinger 2003; Leithwood et al. 2008; Leithwood and Jantzi 2006; Silins 1994). Research shows that transformational leadership behaviors can support organizations in effectively implementing educational innovations (Geijsel et al. 2003; Leithwood and Jantzi 2006). According to Leithwood and Sun (2012) “Transformational leadership theory claims that a relatively small number of leadership behaviors or practices are capable of increasing the commitment and effort of organizational members toward the achievement of organizational goals. The values and aspirations of both leader and follower are enhanced by these practices” (p. 388).

Moreover, transformational leadership can lead to changes in teacher practice (Geijsel et al. 2009; Leithwood and Jantzi 2006). Transformational leadership can lead to commitment by teachers to the reform, and can increase the effort they are willing to devote to such reform. Furthermore, the more school leaders engage in transformational leadership behaviors, the more likely teachers are to take risks in developing and implementing new knowledge (Geijsel et al. 2003; Nguni et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2002).

Therefore, transformational leadership behaviors and strategies could also be important for successfully implementing and sustaining data use in schools. The data team intervention can be described as an educational innovation that is being implemented in the school, for which the commitment and effort of teachers and school leaders are required. The data team is working together towards two organizational goals: implementing data use practices in the school, and solving a specific educational problem. Transformational leadership behaviors can support a team in achieving these goals. Therefore, the transformational leadership model was identified as a suitable framework to serve as the starting point for studying the role of school leaders in data teams. In the next sections, we will describe the transformational leadership behaviors and strategies (components) in depth.

Transformational leadership component 1: Initiating and identifying a vision

Initiating and identifying a vision refers to a leader’s role in contributing to building a shared vision, norms, goals, and priorities in schools (Moolenaar et al. 2012), as well as a more specific shared vision and norms for learning and improvement through data use (Park and Datnow 2009; Schildkamp and Kuiper 2010; Wayman et al. 2012). Thus, contributing to building a shared vision means that school leaders express and communicate goals and the approach for achieving these goals. In this way, transformational leaders may build teachers’ emotional attachment to the school. This can increase teachers’ commitment to the organization, their identification with their school’s vision, and their internalization of school goals as personal goals, which may results in greater efforts of teachers towards realizing these organizational goals (Geijsel et al. 2009; Thoonen et al. 2011).

Related to the data team intervention, we expect school leaders to, for example, communicate school management’s beliefs about data use, related goals and the approach for achieving these goals. In the data team intervention, learning and improvement through data use is an explicit goal, in addition to solving the school’s problem based on data. By committing to these goals, school leaders provide direction for teachers for participation in data use. Moreover, together with the other data team members, norms and structures for safe data discussions should be developed, as well as a vision for (sustained) data use in the school.

Transformational leadership component 2: Providing individualized support

Providing individualized support represents a leader’s attempt to understand, recognize, and satisfy teachers’ concerns and needs while treating each teacher as a unique individual (Thoonen et al. 2011). Mentoring and coaching of teachers plays an important role in this, for example by delegating challenging tasks to teachers, by providing feedback, and by recognizing and talking to teachers about their needs and concerns (Thoonen et al. 2011). Furthermore, by coaching, delegating challenging tasks, and providing feedback, school leaders may help to link teachers’ current needs to the school’s goals and mission and enhance teachers’ sense of self-efficacy (Thoonen et al. 2011, p. 508). Individual concerns, emotions and questions might impede collective learning. School leaders should recognize this and provide individual support to team members to overcome such concerns or negative emotions when they are present. Moreover, it is important that school leaders establish structures for collaboration (Thoonen et al. 2011), such as a systematic data team approach.

With regard to the data team intervention, we expect school leaders to pay attention to this aspect of transformational leadership by, for example, facilitating data use through scheduling time (including accessing, analyzing, and reflecting on data) and providing training related to data use (Roehrig et al. 2008; Schildkamp and Kuiper 2010). Leaders can also show that they recognize and are trying to satisfy teachers’ needs related to implementation of data use by establishing structures that promote regular, consistent, and collaborative data use in schools (Schildkamp and Kuiper 2010; Wayman et al. 2012).

Transformational leadership component 3: Providing intellectual stimulation

Transformational leaders who provide intellectual stimulation encourage teachers to challenge their beliefs and assumptions about daily practice; they collaborate with teachers, (Geijsel et al. 2009; Thoonen et al. 2011) and increase teachers’ ability to solve school-level problems (Thoonen et al. 2011). Transformational leaders stimulate creativity and professional development by encouraging teachers to question their own beliefs and values, and by enhancing their problem solving abilities (Geijsel et al. 1999; Thoonen et al. 2011).

With regard to the data team intervention, leaders can challenge teachers’ beliefs and assumptions about their daily practice, for example, by modeling data use practices (Wayman et al. 2012; Young 2006). A skilled school leader who acts as a role model for data use can stimulate teachers in using data, lead discussions about data and data use, and engage teachers in those discussions. For example, in the context of data use, a school leader could ask questions when teachers make assumptions, such as ‘What (data) is your statement based on’? This helps teachers reflect on how their daily work is influenced by assumptions that might not hold up if investigated. Moreover, school leaders actively participate in the data team, and share and develop knowledge with the team.

Transformational leadership in this study

We assume that initiating and identifying a vision, norms, and goals, providing individualized support, and providing intellectual stimulation promote the process of data teams (see Fig. 2). In this exploratory study, we focused on the following research question: How do formal school leaders apply leadership behaviors and strategies to support the work of the data team in the data team intervention?

Method

Having defined leadership as a process engaged in over time, taking place within a complex system, we conducted a longitudinal exploratory multiple case study investigating formal leadership behaviors in data teams (Yin 2003).

Context

The data team intervention was developed to support educators in gaining knowledge and skills regarding effective data use. In the data team intervention, one or two school leaders are part of the data team. In Dutch secondary schools, school leaders function at different levels. First, there is a principal who leads the school. Next, some schools have assistant principals who directly support the principal. If schools have different tracks (e.g., a track for pre-university education, a track leading to polytechnics, and a track for intermediate vocational education), each track also often has a team leader who reports to the principal. All of these different school leaders collaborate in school management teams. When talking about school leaders who participate in data teams in this article, we mean a person who fulfills one of these formal functions described above.

Each of the four data teams participating in this study consisted of school leaders, teachers and internal data experts. Most of the membersFootnote 1 participated voluntarily, because they wanted to learn how to use data and/or solve a specific educational problem. Each team was supported by the same external data team coach from the university (not one of the researchers). The external data coach participated in every meeting, but was not present at the school outside those data team meetings. The data coach did not work with school leaders specifically, but supported the entire data team. Meetings were held every 3–4 weeks and typically lasted 90 min. The data coach’s task was to monitor the data team’s process and give just-in-time support while the team was going through the eight steps of the data team cycle. The coach supported the team in each of the eight steps, such as developing a clear and concrete problem definition, formulating measurable hypotheses, and providing support in analyzing the data. Furthermore, the intervention included a comprehensive set of guidelines and activities to support the team, which the coach used as a basis for guiding the team. Finally, the coach steered the process, for example, by preventing the team from jumping to conclusions (e.g., when team members wanted to develop improvement measures when they had not analyzed the data yet).

Cases

Overall, a total of 14 data teams from 14 different schools participated in the data team project; all their schools participated voluntarily. We selected four case study schools from the larger project to study leadership behaviors in-depth and over time. We conducted a cluster analysis among all the data team schools. Respondents in each of the schools had completed a survey on their data use practices (i.e., data use for instruction and school development, including questions such as ‘student achievement results are used to identify gaps in our curriculum’, and ‘to what extent do you set learning goals/targets for individual students?’) for a previous study (see Ebbeler et al. 2016 for more details on the survey). The survey was completed by teachers and school leaders (data team members and non-data team members in the school; N = 277). The survey gave us an overview of the extent of data use practices of each of the 14 schools. A hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method (Burns and Burns 2008) was conducted to identify different data use school clusters. The individual survey responses were aggregated to school level. All the schools were clustered into groups based on (their perception of) their amount of data use at the start of the project. Schools could score between 1 and 4 (1 = low data use, 4 = high data use). This resulted in three different clusters: (1) low data use (m = 2.57, sd = 0.15), (2) average data use (m = 3.02, sd = 0.09) and (4) high(er) data use (m = 3.44, sd = 0.09). We wanted to select schools from each of these clusters, to highlight variation in the use of data at the start of the project. Moreover, we expected that the role of the school leader might be different in schools that are using data frequently compared to the role of the school leader in schools where there is less data use. Next, to be able to compare the cases, we wanted to include four schools, one high data use school, two average data use schools (since most of the schools belonged to this cluster), and one low data use school. from all three clusters we selected a total of four cases based on the following criteria: the presence of at least one school leader, one internal data expert, and at least three teachers during the data team meetings.

The four data teams (Fairhope, Newpoint, Monarch, and Village) were followed during the period that they had support from an external data coach (1.5–2 yearsFootnote 2). Information on the four schools can be found in Table 1. At the start of this study, the score for Fairhope’s school put it in a cluster that can be characterized as high(er) data use (cluster 3), while Village’s school was part of the cluster of schools that scored the lowest on the survey on data use (cluster 1). Newpoint (cluster 2) and Monarch (cluster 2) scored in the average category.

Instruments

A total of 90 interviews were conducted to collect perception data about respondents’ view of the role of the school leaders in the data team. All data team members and external data coaches were individually interviewed three times during the support period. A semi-structured interview protocol was used in conducting the 1-h individual interviews with each team member. The interview protocol included questions about the roles, responsibilities and tasks of the school leaders in the team. Respondents were also asked to describe interactions with the school leaders participating in the data team.

The interview protocol was validated for the context of this study by an expert group: two researchers with teaching backgrounds and a researcher with experience conducting interviews in Dutch secondary schools. Based on the results of their validation, small adjustments were made to the interview protocol, including adjustment of the wording of the questions, addition of some prompts, and slight adjustment in the order of the questions and prompts. The interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently summarized. These summaries of the interviews were sent to the individual respondents for a member check. All respondents agreed with the content and confirmed their description of the roles.

Along with the interviews, data used for this study included a selection of audio observations of the team meetings (i.e., all the meetings were audio-recorded), in order to triangulate the team members’ perceptions. During the support period, five audio observations of data team meetings were collected for each data team: when the data team began working together (November 2011/January 2012), 6 months later (June 2012), after the summer holiday (September 2012), 4 months later (January 2013), and before the summer holiday (May/June 2013).

Analysis

The interviews and the audio observations were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were coded by applying an ‘a priori’ coding scheme (Weber 1990) (see Table 2), that was developed based on the theoretical framework. The same coding scheme was used for the observations and interviews, as we were interested in leadership behaviors as they became visible from the observations as well as from the interviews. After a first round of deductive coding, we were left with several quotations that did not match our pre-defined coding list. We conducted a second round of inductive coding. Two codes, originally not included in our coding scheme, arose from the data: creating a climate for data use, and networking. The coding was conducted by author 2. To determine the inter-rater reliability, two researchers (authors 2 and 3) coded five pages of the same fragments independently (Miles and Huberman 1994). Inter-rater reliability was calculated and determined to be an almost perfect Cohen’s kappa of 0.83. After coding, the results were translated into English. Next, a within-case analysis was conducted, followed by a cross-case analysis with comparisons between the four cases on each sub-code emerging from the theoretical framework and the data.

Results: Within-case analysis

In this section, in line with Table 2, we will describe the leadership behaviors displayed by the school leaders in the data teams by narrating their stories.

Team Fairhope Footnote 3

Fairhope data team process synopsis

Fairhope (see Table 3) focused on geography students’ disappointing final examination results. They first investigated two hypotheses that the data showed had to be rejected: a hypothesis concerning students coming from different school locations that were the cause of low average performance, and a hypothesis concerning students who score low on subjects such as physics and chemistry, also score low on geography. They further investigated their data and noticed that students mainly had problems with specific exam questions, namely productive questions. The results of their data analysis also showed that the correlation between the grades in the first 3 years of the curriculum and the final years also needed improvement. Based on these conclusions, the team formulated and implemented several improvement measures. For example, they decided to use a formative assessment approach in the first 3 years of the curriculum, including questions that would (better) prepare students for the final exams. Moreover, they started practicing more with productive questions, starting the year before the final exam. The year after implementation of these measures, the final examination results improved significantly (see Poortman and Schildkamp 2016 for further details).

At the beginning, three school leaders participated in the team (William, Jacob, and Frank). Frank left the team shortly after it started due to competing work demands, but also because data team members had the feeling that they could not speak up during the meetings, which led to a lack of trust within the team. William was the chair of the team in the first 6 months, and then passed this task to one of the participating teachers. All teacher members were geography teachers, who were told by the school leaders that they were expected to participate in the data team as the educational problem the data team was going to focus on was their area of expertise. In the second year, a teacher from another subject area participated voluntarily in the data team. At the end of the support period the team had implemented and evaluated improvement measures to solve their problem. Furthermore, a new data team was established to solve another problem.

Fairhope: Initiating vision and norms

At the start of the support period, the school did not appear to have a vision for data use. In the first round of interviews, several teachers expressed the idea that the vision was rather vague:

It [the vision] is very vague, not specific enough. There are no guidelines that give direction to me as a teacher…In first instance, the school leaders or maybe the board of our school has to formulate a specific vision with norms. Up to now, I have hardly seen a vision. (Liam 1 I1)

However, the vision of the school leaders became clearer during the process, and seemed to be collectively developed in the team. In the interviews the teachers talked about the importance of using data or evidence when making decisions. During the entire support period, school leader William started actively communicating a vision for the implementation of data use by means of the data team, specifically during the first, fourth, and fifth observations.

Furthermore, the data team created norms for the use of data. For example, the interviews and observations showed that new norms for the use of data management systems were formulated. Until Fairhope started its research, teachers at this school entered only the examination marks for the first five students (in alphabetical order) in their class. These results were used for making national comparisons. However, when the data team needed access to these data, they found that the results of these five students were not sufficient for conducting further research. They also discovered that they could not track the results of the remaining students in other data management systems. Therefore, the school leaders who participated in the data team decided that each teacher must enter the examination results for all students in the data management system. The team agreed that it was important to establish this new norm, to make the work of future data teams easier.

In the end, school leader William succeeded in setting up a new data team with teacher Liam, to further implement data use within the school after the support period had ended.

Fairhope: Individualized support

The teachers in the team were all being paid extra for the hours they spent working with the data team. Most respondents appreciated the monetary support, but also indicated that they would have rather been supported with time (e.g., fewer hours of teaching to free up time for data team participation). Not everyone was positive about the monetary support:

You have bad achievement results. And you get rewarded to work on it… It is ridiculous really…. Of course, I will invest hours in this. It is about those achievement results, and not about enriching yourselves with a couple of euros extra per month. (teacher Simon I3)

The school leaders also tried to provide other forms of support. For example, school leader Jacob facilitated data use by proactively communicating with other school leaders about buying a new data management system that worked better than the existing one. School leader Jacob was also the one who made sure that every team member was supported so as to be able to contribute to the team:

Of course, in my duty as school management team member, this also means if you have got a question about how to do something, something costs money, or you need more time, or whatever it is you need, then I hope that you pose that question, so that we can support you. That is really important and that needed to be said. (WilliamO4)

School leader William also reported that he had individual meetings with teacher members of the data team before the team started. In these individual meetings he tried to convince the teachers of the importance of the data team work. During these meetings he tried to communicate the vision and goal of the data team to the individual teachers. When the team started, school leader William and school leader Jacob were available for teachers who needed to talk about the data team, for example, about emotions or new ideas. School leader Jacob (I3) stated that he noticed during the data meetings that teacher Lily seemed to be frustrated about something. Whereas in the beginning she gave the team a lot of input, she did not do this anymore. Therefore, he organized an individual meeting with teacher Lily, and in this meeting he tried to encourage her to speak her mind more often in the team. This teacher stated that she was very annoyed with the unwillingness to change of one of the data team members, and she discussed this with school leader Jacob:

He is a bit ‘old school’, no change, that is better…. But I think that we need to change, otherwise we will get stuck. I got irritated. I discussed this with the school leader… he understood where I was coming from. He had also noticed it. (teacher Lily I3)

Fairhope: Intellectual stimulation

The observations and interviews showed that the school leaders in the team stimulated discussions, structured discussions, and engaged members in discussions, such as by asking questions, and by making statements that would lead to discussions. School leader William (I3) stated, for example, that he started asking the team to “prove it, or provide proof that supports the contrary”.

In the first two observations school leader William was evidently leading and structuring discussions. However, he was also the appointed chair of the data team. In that respect he had the role of structuring the meetings and discussions. However, school leader William also distributed leadership. School leader William’s task during the first 6 months was to lead the meetings and to set up agendas. After that time, he delegated this chair task to teacher Liam. The observations also show that school leader William delegated tasks, and in the final interview round school leader William stated, for example:

My strong aspects are this, your strong aspects or that, so it may be wise if you do this and I do that, and we can complement each other. (…) let’s divide our roles in a way that makes the entire team stronger. (school leader Jacob I3)

Furthermore, the school leaders listened to team members’ arguments and opinions in sharing decisions, for example, when choosing a hypothesis that the team was going to test. School leader William was also a role model for data use and collaboration in the data team. For example, school leader William completed tasks just like the other data team members and collaborated with the data expert, in order to analyze the data. The data expert Amy noted that the school leaders collaborated intensively with the teachers, and were really perceived as part of the team:

The school leaders are closely connected to the workplace, so to the teachers, they also participate in joking around. (……).The border between school leaders and teachers is small. (data expert Amy I3)

Although the school leaders were part of the team, they were also expected to steer the process as needed, which according to themselves they did. In the interview the school leaders were asked if and how they steered the data team process. According to school leader William, for example, he steered the process when necessary, and also explained why he steered and put pressure on the team to make changes:

Euhm, okay guys, this has been said a hundred times before, and everybody agrees, and yet there is another BUT. Just do it this time, go work on it…..… I have said, this is what we are going to do, and it will take more time, but it is important for yourselves, and especially for the student, and this is what it is all about. (school leader William I3)

Although not included in the definition of intellectual stimulation, teachers considered knowledge input by school leaders and their access to data as an important aspect of intellectual stimulation. During the three interview rounds, they reported that the school leaders complemented each other’s knowledge and in that way contributed knowledge to the data team. While school leader William had knowledge about statistics due to his background in mathematics, knowledge about using Excel to analyze data, and knowledge about where to get access to certain data, school leader Jacob had pedagogical content knowledge about the subject, because he taught geography before being a school leader. Due to his pedagogical content knowledge, school leader Jacob was able to discuss content matters with the teacher members. However, his knowledge about the subject and the related pedagogy was not appreciated nearly as much as school leader William’s knowledge about data and statistics. In the observations it was apparent that these school leaders also had additional knowledge about school policy, school statistics, and some knowledge about the data management system which they shared during team meetings. Teacher Liam, for example:

School leader William conducted his magic with the numbers, which I initially found hard to grasp, that nobody really understood. But he opened the doors to the data we needed, to analyze, to calculate. (…). He gave us access to the data we needed to investigate our hypotheses. (teacher Liam I3)

Fairhope: Climate for data use

Although it was not included in our theoretical framework, we found that school leaders were also important for shaping a climate for data use within the data teams. Due to disappointing geography results on the final examination, Fairhope’s school management team thought that a data team would be a good way for geography teachers to work collaboratively on a solution for this problem. Furthermore, the school management team hoped that the data team would stimulate collaboration among geography teachers. Although the teachers recognized that there was a problem with the final exam results, they felt that they were being punished for their students’ disappointing examination results, especially at the start of the data team. However, the teachers’ commitment to the data team grew quickly.

In contrast to other data teams who reported an open atmosphere during their first round of interviews, Fairhope struggled with a lack of trust between teacher members and the school leader who had left. All interviewees reported a lack of trust between some members and this school leader. According to the internal data expert, team members did not dare to share their own opinions, due to this lack of trust. As a result, the school leaders decided that it would be better for the team if school leader Frank left. Trust remained an issue for a while, even after school leader Frank had left the team. For this reason, the team agreed upon some rules: School leader Frank would only be informed about the progress of the team if the data team wanted to implement measures that would influence the curriculum, and therefore needed his permission as a school leader. This discussion helped in creating an open climate for data use. In the second and third round of interviews, respondents were more positive about the atmosphere in the team and described it as open. For example, teacher Liam described how school leader William was open to critique. Several teachers talked about the trust and openness in the team, for example:

Nobody has a hidden agenda….Everything is discussed openly, what we think, what we thought, which is very different sometimes. (teacher Lily I3)

Fairhope: Networking

Although use of the school leaders’ network was not included in the theoretical framework, team members frequently mentioned its importance. School leaders in Fairhope mentioned using their network with other school leaders and teachers. They reported in the observations and interviews that they discussed data team related matters during school management meetings.

[During school management team meetings, the school leaders ask me:] Is there any news from the data team? What is the state of the art? What did you guys do? Give us an update…And that also resulted in the fact that there will be new data teams at our school. (school leader Jacob I3)

They also used their school leader’s network for contacting potential teacher members from other school buildings. And they used their network with teachers within the school for contacting new teacher members within their own school building.

Team Newpoint

Team Newpoint data team process synopsis

Newpoint focused on the retention rate in the 4th grade of senior secondary education (students 15–16 years old). The team first investigated the hypothesis about whether the amount of homework influenced these retention rates, which turned out not to be the case. Thereafter, the team interviewed students about the retention rates. The interview results indicated that possible causes included a lack of parental support, a lack of student motivation, unrealistic expectations with regard to student planning and self-regulatory skills, a lack of curriculum coherence across the grades, low expectations of mentors which led to self-fulfilling prophecies, and low instructional quality (e.g., instruction was not adapted to the needs of students). At the time that the support ended, the team had not yet succeeded in implementing improvement measures based on these results.

All teacher team members participated voluntarily in the data team. They were either asked by their direct leaders whether they wanted to participate, or they applied to be a data team member. Newpoint had a high turnover rate of school leaders participating in the data team (see Table 4).

At the beginning of the data team project in November, Charles and Truman participated as school leaders in the data team. After a few months, Charles left the school. Hank, who was also the school principal, replaced him in the data team. After the summer holiday, Truman also left the school. Robert and Stacy were supposed to be the new school leaders in the data team, together with Hank. However, after a few months Stacy left the data team due to competing work demands, and was not involved with the work of the data team anymore.

Newport: Initiating vision and norms

At the start, school leaders communicated visions, goals and norms for data use in the data team. In one of the first meetings, for example, school leaders Charles and Truman expressed that they expected team members to be present at all team meetings, to show interest during team meetings, and to work toward solving an urgent problem at their school. Expectations were also expressed with regard to working with the data team intervention. In the data team’s first meeting, it was evident that the school leaders expected the data team to help with implementing data use within the whole school in the next 2 years.

Within the first year of the support period, both Truman and Charles left the school. Although the team was expected to help with implementing data use and communicating the data team’s results within the school, the external data coach reported in the second interview that Hank, the principal of the school who joined the data team, failed to communicate a vision for data use in the data team. A lack of vision by school leaders participating in the data team also emerged in the discussions at the last observed meeting. A quite lengthy discussion showed that Robert, a school leader who had replaced Truman, had no idea how the principal, Hank, wanted to facilitate data use and the activities of data team members within the school after the support from the external data coach ended.

When the support period ended, data team members were supposed to help their departments with the implementation of data use. They were supposed to be the experts and every now and then would meet with the other data team members to exchange experiences and seek feedback from other former members of the data team. Soon, some team members reported having difficulties, because their departments asked for too much and because a vision and goal for data use were still lacking within the school.

Team Newport: Individualized support

Principal Hank supported the data team members. For example, he made sure that team members took time for a brief evaluation and reflection at the end of each meeting, where members could articulate what they thought about the meeting. Principal Hank also talked to individual members of the team in order to discuss the emotions that were aroused during meetings.

…I talked to Hank. I was dissatisfied with my participation in the data team…frequently, I was disappointed about the progress of the data team…we talked about this issue… (teacher Mason I2)

Also, one of the school leaders facilitated the data team meetings by serving as chair. For example, many members appreciated that school leader Truman made agendas for team meetings, monitored the time schedule during team meetings, summarized the different opinions and the conclusions from the discussions, delegated tasks, and reformulated the team members’ arguments to make them clearer. This behavior was also evident in the observations.

Newpoint: Intellectual stimulation

The observation and interview results show that school leader Truman acted as a role model for data use in the data team in terms of leading discussion as well as actively collaborating with the teachers. For example, he collaborated with other team members in completing ‘homework’ related to data team activities. After Truman left the school, it was reported in the second and third round of interviews that Robert took over some of these behaviors, such as collaborating with other team members between meetings, leading and structuring discussions. School leader Stacy reported in the second round of interviews that she tried to stimulate discussions by probing comments made by other members, summarizing conclusions and keeping track of decisions. However, this was not confirmed by other members, nor by the observations.

Furthermore, the school leaders wanted to empower the other data team members by engaging members in distributed decision making. For example, principal Hank stated in the interviews that he intentionally chose to let another member of the data team act as chair and intentionally gave other team members the opportunity to speak first.

Several data team members stated in the interviews that the school leader replacing school leader Robert contributed a lot to the meetings due to his knowledge about doing research and statistics. He also shared his knowledge with regard to policy, trends, and processes in the school. Finally, the team was able to use his knowledge with regard to accessing data. In the observations of data team meetings, it appeared helpful for the team that the school leaders had direct access to all data, knew about trends in the school and school statistics (e.g., number of students obtaining their diploma without delay, or results of research that had been conducted in school), and had additional knowledge about processes within the school (e.g., meetings that took place about certain topics, or where to ask for additional tools needed for accessing data) and school policy.

Newpoint: Climate for data use

The interview and observation results for this team showed that the climate for data use was characterized by a flat hierarchy (i.e., there was no hierarchical difference between school leaders and other team members during discussions) and an open atmosphere in which members shared their opinions with each other. On the whole, a dip in the climate for data use was observed throughout the second year. Data team members indicated that the data team process took longer than anticipated, and that they had expected results sooner. According to the external data coach, one data team member even stated that he only participated in the data team meetings because the principal asked them to do so. He also told the external data coach that if they had the choice, he would immediately stop participating in the data team. Moreover, school leader Stacy did not give priority to team meetings, and finally left the team due to competing work demands. Hank was also absent more often.

Newpoint: Networking

Team members frequently mentioned the importance of the school leaders’ network. Hank expressed in the third interview round that it is important to have school leaders in data teams and regretted that he and Robert apparently did not communicate enough about the data team during school management meetings in order to create commitment for data use in the school. Principal Hank stated (I3):

Recently, we have asked a number of departments to hand in plans in order to improve their results. These plans contain good intentions to improve the results, but the quality of the plans and the way they want to reach their goals…and some of them have tried to analyze the possible causes for their disappointing results, but most of them are only based on intuition. Now I think that we as school managers should have started highlighting the importance of implementing [data use] much earlier.

Team Monarch

Team Monarch data team process synopsis

Team Monarch (see Table 5) focused on the declining number of students passing their final year of pre-university education. Benjamin and Abigail were the two participating school leaders in the team. They selected the teacher members based on applications. First, the team investigated whether more boys than girls failed, which was not the case. Secondly, the team investigated if students with a gamma profile (e.g., languages, social sciences) were more likely to fail than students with a beta profile (e.g., physics, mathematics, chemistry), which was not the case either. Next, they conducted interviews with students on what according to the students the causes of this problem were. The students indicated that a lack of motivation was a likely cause. The team was looking into motivation, when the support period ended. At the end of the support period, Monarch had not reached the point of being able to formulate improvement measures. The team members tried to meet after the support period had ended, but did not succeed in doing so on a regular basis.

Monarch: Initiating vision and norms

The results from the observations show that school leader Benjamin created norms for data use, for example, by highlighting that falsifying hypotheses is also an important result. This led to the norm within a data team that statements should be corroborated by data, which was deemed to be important by all data team members. Both school leaders also expressed a vision for data use after the end of the support period and communicated expectations regarding communication with colleagues about the data team’s results. Although the data team members still wanted to finish the research and implementation of the steps they had begun to take, the frequency of data team meetings also decreased when the support from the external data coach ended. Despite their enthusiasm and enjoyment during the meetings, the data team was not very active, because team members did not give priority to the meetings. However, the data team members still wanted finish the research and implementation of the steps they had begun to take.

Monarch: Individualized support

School leader Abigail facilitated the team’s work, for example, by planning team meetings, communicating the location of the meetings, and delegating tasks. School leader Benjamin also facilitated the team’s work in terms of time. For example, he allowed teachers to stop their lessons earlier so that the meeting could be on time. Furthermore, the team was facilitated by being allowed time for activities such as going to conferences about data use and presenting data team results in the school.

Monarch: Intellectual Stimulation

In the first two rounds of interviews, the school leaders were described as acting as role models for collaboration, for example, by meeting between officially planned data team meetings in order to brainstorm about the data team’s next steps. Abigail also collaborated with the internal data expert when data were collected and analyzed. In addition, the school leaders also stimulated discussions and sometimes structured discussions during meetings, although they tried not to take over the role of chair.

Benjamin and Abigail also tried to stimulate team members to participate in training related to statistics and data use, and tried to stimulate decision-making. The observations showed that the school leaders distributed decision-making by letting all members vote about the problem and hypothesis to be studied. School leader Benjamin was a role model for data use in the school, for example, by expressing that he liked doing research. Both school leaders were mathematicians and their knowledge input about statistics and research was appreciated. For example, during one of the observations they explained the meaning of a p value being significant. Though they were mathematicians, they thought it would be useful for them, too, to participate in training related to statistics and data use. It was also observed and mentioned during the interviews that these school leaders had additional knowledge about their school’s data management system, about school policy, about ongoing school processes, and about school statistics.

Monarch: Climate for data use

The climate of the data team was characterized by a flat hierarchy and a trustful and open atmosphere, in which every data team member was able to share his or her thoughts. In the last interview, school leader Benjamin illustrated the atmosphere between teachers and school leaders in an interview, “The fact that I am a school leader has had no influence at all on our discussions”. This open climate was observed in all interview rounds and all observations, which included vivid discussions where anything could be articulated. Abigail also frequently expressed her enjoyment and enthusiasm about the data team meetings:

In the evaluation, Abigail expressed her satisfaction that now there is time to talk about education. This can also be seen in the data team. They really enjoy sharing their thoughts. (teacher Mia I2)

Furthermore, the school leaders’ presence during the data team meetings was important for the team in order to check whether the actions the data team wanted to take would match the school’s vision.

From the start on, I appreciated that members of the school management team were present during the meetings, because sometimes the school’s vision is not that clear. That, of course, gives you a lot of freedom. But if you put a lot of energy into something and in the end you hear that it does not fit the school, that would be awful. So, their presence is also important for creating support among the school leaders. (teacher Nathalie I3)

Therefore, their absence during one or two data team meetings also caused some irritation for one of the data team members.

Monarch: Networking

School leader Benjamin reported that the two school leaders kept the school management team up-to-date about the data team during school management meetings. The two school leaders also used their network for sending out questionnaires and enhancing response rates for these questionnaires.

Team Village

Team Village data team process synopsis

Village (see Table 6) focused on the declining number of students passing the fifth grade of senior secondary education (providing access to polytechnics). School leader Michael participated as a school leader in the data team up until the first summer holiday. After the summer holiday, School leader Chrissy took over his position. They first investigated if the number of students having to repeat a grade in the fourth grade influenced this problem, which was not the case. Next, they investigated whether the results of the end of primary school national assessment could already predict this problem in the fifth grade, which was not the case either. The team was investigating a hypothesis with regard to homework, when the support period ended. At the end of the support period, the data team had not implemented improvement measures. The team struggled with carrying on their work. Some team members reported that they sometimes met in order to continue working, but these meetings were not planned on a regular basis.

Village: Initiating vision and norms

The first observation indicated that School leader Michael did not thoroughly explain his vision, nor did he talk about developing a joint vision. He did express the expectation that the results of the data team would be shared with the rest of the school. According to school management, the high number of failing students in the 4th grade was the cause of the declining number of students at the school passing senior secondary education (5th grade). Although the data team found that this was not the case, school leader Michael tried to hold on to this idea. School leader Chrissy became a member of the data team and replaced school leader Michael. The team let go of the vision concerning the school management team’s problem statement about the problem being in the 4th grade. However, school leader Chrissy never communicated a clear vision for data use either. Furthermore, at the end of the support period, there was no vision regarding how to proceed with the data team. After the support from the external data coach had ended, some of the teacher members tried to meet on their own to finish the data team’s work.

Village: Individualized support

In the observations and interviews for Village, we only found a few pieces of evidence regarding school leaders offering individualized support. In the observations, Michael delegated tasks with regard to data collection, tasks that had to be finished before the next meeting started. As observed in the third meeting, Chrissy also offered assistance for the data team members if needed, in the form of extra members:

Imagining that we would really need somebody, I can always ask someone. However, I don’t want to force it upon someone. (school leader Chrissy O3)

A possible explanation for the lack of evidence regarding individualized support from school leaders is the fact that this data team was set up by teacher Lars who asked people to help him with his plans, which, in the first year, seemed to be more focused on him becoming a teacher leader than on the data team learning how to use data. This teacher completed most of the tasks in the data team and the other members only participated to give feedback. However, Lars realized in year two that working in a data team should be a joint effort:

That was the case in the last year. This year not any longer. The team had the idea that I was the one who wanted to become teacher leader, and that they would just give some feedback. We changed that, because the data team is a project that has to be done jointly… (teacher Lars I2)

Village: Intellectual stimulation

Though not always present, both school leaders who participated in the team stimulated discussion during team meetings and tried to engage the members in the discussion, as noted by the external data coach in the second interview, “She [school leader Chrissy] asks questions like: I don’t get it, is it really like that? Why?”

School leader Chrissy was a role model for collaboration. She worked together with a teacher (teacher Tempe) to make a presentation for teachers about the data team and to find instruments for collecting data in school. This was confirmed by the interview results for several teacher members.

In the first interview, teacher Lars highly appreciated that school leader Michael contributed knowledge about the school that teachers did not have. It also became clear from the observations that School leader Michael knew about school statistics. When Chrissy wanted to present the data team findings to her department, she asked teacher Tina to present the findings collaboratively.

Village: Climate for data use

School leader Michael told the team that the school management team considered the data team important, and tried to create an open atmosphere by telling them that he wanted the teacher members to share their opinions regardless of his being a member of the school management team. However, team members criticized his behavior in the data team. Individual data team members thought that Michael was too protective of students coming from his track who were now in senior secondary education. Furthermore, team members thought that he tried to direct the data team’s research in the direction of his vocational educational track. There seemed to be a lack of trust between the school leader and teachers. When school leader Chrissy took over, she did not give priority to the team meetings. Many team members were not able to describe her role in the data team, because of her frequent absence.

Village: Networking

School leader Michael was the link between the data team and the school management team. According to teacher Tempe, school leader Michael could use his network to communicate questions from the data team during school management meetings. However, the data team did not want to use school leader Michael’s network. They were under the impression, especially in the first year, that one important goal of the data team was to support teacher Lars in obtaining a leadership position, and therefore, the team thought that it was teacher Lars’s task to build up his own network with the school management team, as the leader and chair of the data team.

In the third round of interviews, school leader Chrissy stated that she was the potential link to the school management team, but that she unfortunately had not used her network enough to create commitment to the data team among other school leaders:

To me, it [the data team] is meant to do research, but I clearly see that I have to fulfill the role of communicating between the data team and the management team. I should have communicated more frequently. (School leader Chrissy I3)

Teacher Tempe, teacher Lars, and teacher Bill all explained that Chrissy was the link with the teachers in her own department. The data team used Chrissy’s network to communicate with teachers in her department about the data team and its results. Chrissy herself said that she would be willing to use her network in order to renegotiate facilities for the data team and for contacting new data team members. She wanted to use her network to create commitment for the data team in the school.

Results: Cross-case analysis

In the cross-case analysis, we were interested in comparing and contrasting the type of leadership behaviors found in the teams. The results are summarized in Tables 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Initiating vision and norms

Fairhope was the only team in which school leaders developed a clear vision, norms and goals for data use, together with the team. They had a vision of how to sustain data use (i.e., a new data team would start in which the former data team members could train their colleagues in the use of data), and were able to translate this vision into concrete actions (see Table 7). Not only did this data team solve their problem, also a new data team started in this school after the support period.

The school leaders in teams Newpoint and Monarch also expressed a clear vision, norms and goals on data use, and the school leaders of team Monarch also had ideas on how to sustain data use. However, the school leaders of Newpoint left the school, and the principal who took over was unable to express or develop a clear vision with the team with regard to sustaining data use at the school. Team Monarch had difficulties in actually translating their vision into concrete actions after the support period. The vision was not really concrete at the school of team Village, nor was it directed toward how to sustain data use at the school after the support period.

Finally, an important norm for data use is active participation during all data team meetings. In team Newpoint the school leaders were not present at all the meetings, due to competing work demands, and one of the school leaders eventually quit the data team because of this. They did not make attending data team meetings a priority, which also gave teachers the signal that their data team work was less important to the school leaders.

Individualized support

In general, school leaders in the data teams provided some type of support (see Table 8). This ranged from providing time or monetary compensation (i.e., a bonus) to making agendas and scheduling meetings. In teams Newpoint and Fairhope, school leaders were available for individual appointments with team members, for example, to talk about frustrations. This emotional support was perceived as being very important to the teachers. This type of emotional support was not reported in teams Monarch and Village. Some teachers preferred support with time (e.g., less teaching hours) over monetary support. Moreover, the teachers in Village were not satisfied with the support in terms of time.

Intellectual stimulation

For all four teams, school leadership team members acted as role models for collaborating with team members between meetings in order to finish tasks (see Table 9). Most school leaders also stimulated and led discussions with teacher team members. In Newpoint, Fairhope and Monarch, the school leaders also distributed their leadership by making themselves an equal part of the team, by appointing a teacher as chair, by voting on certain issues, and by collaborating as an equal partner with teachers.

All teams commented about the knowledge of the school leadership team members (see Table 9). The main difference was the number of interview segments related to knowledge. In teams Fairhope and Monarch, most members extensively described the leaders’ knowledge input. In those teams, leaders had a background in mathematics or in the subject that was the team’s focus. Especially in Fairhope, teachers reported that the school leader had a lot of knowledge the team could learn from and use, ranging from knowledge on statistics to pedagogical content knowledge, to policy knowledge. In teams Newpoint and Village, comments related to knowledge were rather scarce.

Climate for data use

All school leaders in the data teams tried to create an open atmosphere (see Table 10). All of them wanted the teacher members to be open, but not all of the leaders succeeded in creating an atmosphere in which all data team members actively participated and discussed their opinions focused on how to improve education. However, certain actions by school leadership team members in teams Fairhope and Village created a temporary dip in the climate for data use, either because the leader was too dominant, or because the leader wanted to establish a vision and goal that was not supported by the team members. In Fairhope an open atmosphere and trust were realized after one of the school leaders left the data team, and the team had an open discussion on how to proceed. Teachers felt that they were able to speak their minds freely, as they felt supported by the school leaders. The data team members then reported about the open climate, where everyone could express their opinion and ask questions.

Networking

Though not part of the framework, it seems important school leaders are the data team’s link to other people in the school, predominantly to other members of the school’s management team. The school leaders of team Fairhope and the school leaders of Monarch really formed this link to other school leaders during school management meetings (see Table 11). They used their network to create commitment for data use and the data team in their school.

Conclusions and discussion

Limitations

In this study we used exploratory qualitative analysis to generate a deeper understanding of leadership behaviors in a data team that may benefit the progress of a team in terms of completing the eight steps of the data team intervention and sustaining the data team intervention. Our aim was to gain more in-depth insights into leadership behaviors and strategies of school leaders who were participating in and supporting data use. We want to stress here that this study was exploratory, only four schools participated in this study, which means that the results can only be generalized analytically (Yin 2003). It was not the aim of the study to identify causal relations between the success of the data team and the leadership behavior and strategies. We aimed to provide an in-depth description based on more extensive case description and comparisons among all four cases. We want to point out here that the results do seem to indicate that the team with the best outcomes, in terms of solving their educational problem and continuing with the data team intervention (team Fairhope), was also the team in which we found the most enabling leadership behaviors.

The five leadership building blocks for data-informed decision making

The results of this exploratory study indicate that all school leaders participating in the data teams, but especially in team Fairhope, enacted several important leadership behaviors and strategies when participating in the teams. We have identified five building blocks for school leaders who want to build effective data teams. In the next section, we will explain these building blocks based on the results of our study. Each building block ends with a figure summarizing the main questions school leaders need to ask when building effective data teams in their school.

Building block 1: Initiating and identifying vision, norms, and goals

Similar to other studies (Farley-Ripple and Buttram 2014; Levin and Datnow 2012; Young 2006) the results of this study show that the first building block is having and communicating a clear vision, norms, and goals with regard to the intervention in which a school participates, including norms and structures that enable safe and confidential discussions about data (Marsh 2012). School leaders need to develop and discuss vision, norms, and goals together with the teachers in the team.

However, the results of this study also show that this is not enough. School leaders may also need to think about how to sustain the work after the support for the intervention has been withdrawn. Moreover, this vision has to be translated into concrete actions. Only in team Fairhope was the school leader able to translate the vision into practice. Therefore, it is important to link this type of transformational leadership to what is called an organizational routine, where an organizational routine refers to re-occurring interdependent actions that involve multiple actors, which structure everyday practice in schools by supporting and focusing interactions among school staff (Feldman and Pentland 2003; Spillane 2012). Data use in Fairhope seemed to be on its way to become an organizational routine, which the school leaders had helped creating. The data team had solved the problem it was working on and a new data team was created.

The results also point to the importance of active participation (i.e., prioritizing data team meetings) and continuity of school leaders in a data team during the intervention. Change in school leadership can lead to a disruption of progress and process; that is, sometimes the vision for data use and the goal of the data team can become unclear after the change, trust must be rebuilt, and tasks must be redistributed. Both school leader and teacher turnover can threaten the sustainability of interventions in schools.

Figure 3 summarizes the key question school leaders need to ask when they want to initiate and identify a vision, norms and goals for data use in their school. School leaders can ask themselves these questions, but it is also important to discuss these questions with teachers (in a data team).

Building block 2: Providing individualized support

A second transformational leadership building block is individualized support. Teachers in data teams need to know that they can turn to their school leaders to talk about their emotions related to the data team’s activities. Furthermore, the results of this study show that emotional support is also crucial. Teachers need to feel that they are able to discuss their emotions, concerns and frustrations with the school leader. Moreover, the work of the data team members needs to be facilitated (e.g., see also Marsh 2012), for example in terms of time, but also by establishing structures for collaboration. Figure 4 summarizes the key questions school leaders need to ask when they want to provide individualized support for data use in their schools

Building block 3: Providing intellectual stimulation

The results also show how the third transformational leadership building block intellectual stimulation can be applied, in terms of school leaders collaborating with teachers, being a role model when it comes to data use, providing access to data, and distributing leadership (e.g., appointing a teacher as data team chair). Teachers need to feel that the data team has enough autonomy to actually make decisions that will be implemented. Other studies also point to the importance of distributed leadership in the use of data (Kerr et al. 2006; Sutherland 2004; Wayman and Stringfield 2006; Wohlstetter et al. 2008; Young 2006).

Another important leadership behavior within this building block is knowledge sharing. School leaders can contribute different types of knowledge to the team: organizational knowledge, knowledge about data, statistics, and research, and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). School leaders often have a different perspective on the problem the data team is studying and can contribute different types of knowledge a team can use. Figure 5 summarizes the key questions school leaders need to ask when they want to provide intellectual stimulation.

Building block 4: Creating a climate for data use

Although this aspect was not originally included in the transformational leadership framework developed by Leithwood (e.g., Leithwood and Jantzi 2006) and in our coding framework, the results of this study indicate that creating a climate for data use is a necessary building block for implementing and sustaining data use. Trust and respect are crucial components of this climate. Moreover, it seems that intellectual stimulation and individualized support can contribute to this open climate. The results show that the teams that felt supported by their school leaders also reported an open climate, which seemed to arise as a result of feeling supported. Obliging teachers to participate does not contribute to an open climate. As stated by Datnow and Park (2018) then power issues may arise, where school leaders use data use as a form of managerial control. This can cause resistance, a lack of ownership, and a lack of willingness to work in a data team to improve education. As stated by others (Copland 2003; Datnow et al. 2013; Horn and Little 2010; Park and Datnow 2009), collaboration, trust, and the willingness and capability to address conflict are necessary ingredients for the use of data.

Moreover, to create this climate of data use, school leaders can focus on what Hargreaves et al. (2018) call collaborative professionalism. Educators need to build trusting relationships, use precise strategies and protocols together, for example, such as specified in the data team intervention, and need to provide each other with feedback and engage in reflective in-depth dialogue together. School leaders can help set the tone for this by stressing that the focus is on data use for improvement instead of accountability and that data teams are a place for genuine inquiry around student learning and school improvement (Datnow and Park 2018). Figure 6 summarizes the key questions school leaders need to ask when they want to create a climate for data use.

Building block 5: Networking

The results of this study point also to one last building block not included in the transformational leadership framework developed by Leithwood (e.g., Leithwood and Jantzi 2006) and in our coding schema: Networking. Although networking is not a behavior that is typically described as a transformational leadership behavior, the results of our study show that the school leader can form the link between the data team and other (management) colleagues in the school, thereby spreading the data team’s knowledge and creating commitment for data use at the school (i.e. a form of ‘boundary crossing’). To create effective schoolwide and sustainable data use practice, school leaders, but also teacher team members need to act as ‘boundary crossers’ (Akkerman and Bruining 2016) to share their knowledge with others in the school, the wider school community, and reflect on the consequences of what they have learnt together with their colleagues. Figure 7 summarizes the key question school leaders need to ask when they want to engage in networking.

Conclusions

The importance of some of these building blocks has been stressed in other studies. For example, several systematic literature reviews have been conducted in the field of data use the last couple of years (e.g., Datnow and Hubbard 2015, 2016; Hoogland et al. 2016). These three reviews mention the importance of the following three building blocks: Establishing a vision, norms, and goals, intellectual stimulation, and creating a climate for data use. In these reviews, summarizing the state-of-the-art literature on data use and leadership, the importance of networking and providing individualized support, for example in the form of emotional support, are not included. From the literature on social network analysis we know that social capital, networks, and the role of the school leader in these networks, are crucial for school improvement initiatives (e.g., Moolenaar et al. 2010), and this study gives us more insight into the role of the school leader in this regard. School leaders need to provide individual data team members with individualized support, for example in the form of emotional support, but they also need to make sure that they link the (individual) data team (members) to the wider school community.

This study does not only simply list the building blocks, but also provides clear steps for practice to work on these building blocks in the form of questions for school leaders, and provides insights into the interaction of these building blocks. All the building block interact with each other, we will give an example here of the interaction of three of the building blocks derived from team Fairhope. For example, for this team the building blocks emotional support, creating a climate for data use, and networking seemed to interact with each other. School leaders who were easy to approach for individualized support (e.g., were available for teachers to talk in individual meetings), were better connected to the teachers in the data teams, as well as connected to the wider school community, for example to find new teacher members for the data team. This also seemed to lead to a climate in which the data team was willing to invest in using data to improve education.