Abstract

Objectives

Positive Behavioral Support (PBS) is considered the treatment framework of choice for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) at risk of behavior that challenges. PBS demands stakeholder engagement, yet little research has explored goal formation in this context for caregivers of children with IDD.

Methods

We used Talking Mats and semi-structured interviews to support 12 caregivers of children with IDD who displayed behaviours that challenge, to develop goals for PBS. Interviews covered quality of life for caregivers and their child, adaptive and challenging aspects of child behavior, and aspects of caregiver’s own behavior.

Results

Caregivers were able to form individualised and meaningful goals in relation to all domains, demonstrating rich insight into personal needs and needs of their child. The process of forming goals was psychologically and emotionally complex given prior experiences and needs of participants but effectively supported by the interview method.

Conclusions

We conclude that goal formation in PBS requires careful consideration and structuring but has the potential to support effective working relationships and ensure assessment and intervention is aligned with the needs and aspirations of families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Children and young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are at high risk of developing behaviors that challenge (BTC) (Totsika et al. 2011a, 2011b). By definition these behaviors have a negative impact upon an individual’s wellbeing and life quality (Emerson 1995; Emerson and Einfeld 2011) and impact negatively upon the wellbeing and life quality of those who care for them (Baker et al. 2003; Hastings 2002; Woodman et al. 2015).

Positive Behavioral Support (PBS) provides an evidence-based and ethical approach to supporting people with IDD in relation to BTC through a synthesis of Behavior Analytic (Baer et al. 1968) and Person Centred (Kincaid and Fox 2002) approaches. The PBS framework aims to increase skills, arrange opportunities and alter environments in accordance with individual needs and aspirations, to bring about positive changes in Quality of Life (QoL) and reduce risk of BTC over the long term (Carr et al. 2002; Gore et al. 2013; Horner et al. 1990; Kincaid et al. 2016). Strategies and interventions selected within the framework should therefore be highly individualised, rich in social and ecological-validity and linked to socially and personally meaningful outcomes (Carr et al. 2002; Carr 2007; Gore et al. 2013).

The person centred foundations of PBS call for close collaboration between practitioners and stakeholders (Dunlap et al. 2008; Gore et al. 2013; Lucyshyn et al. 1997; McLaughlin et al. 2012). In the case of children, this typically includes working in partnership with family caregivers who are likely to know the child best, be experiencing the impact of behavior that challenges (BTC) and be highly motivated to invest in positive change (Dunlap and Fox 2007, 2009; Gore et al. 2014). Caregivers’ own behavior is also often interconnected with that of their child (Hastings et al. 2013) and therefore needs consideration in and of itself at a systems level.

Whilst PBS has often focused on family contexts (Durand et al. 2012; McLaughlin et al. 2012), caregivers of children with IDD and BTC, still report feeling marginalised, ill-informed, and not listened to by professionals (Griffith and Hastings 2014). Finding further ways to enhance stakeholder engagement is, therefore, a priority for PBS if support is to be routinely aligned with the needs, aspirations, and life quality of families.

Identification of support goals prior to assessment and intervention marks the earliest clinical encounter between practitioners and families in a PBS pathway. Interactions during this period might well serve to set the scene for working relationships and determine the strength of joint planning that follows. In general mental health literature, idiographic-goal tools are typically valued by professionals and families for such reasons (Edbrooke-Childs et al. 2015; Jacob et al. 2016) and frequently used in general mental health services for children and adolescents (Law 2011; Wolpert et al. 2012). Relative to other procedures, methods for agreeing goals specific for PBS have however received little research attention (Dunlap and Fox 2007) and in practice may be an overlooked opportunity to get things right.

One notable exception has been development of “Positive Goals for Positive Behavioral Support” (PGPBS) (Fox and Emerson 2010): a goals tool based on 38-items outcomes theoretically achievable via delivery of PBS. The tool appears clinically valuable, but has not been the subject of research, beyond an initial pilot (Fox and Emerson 2001). Notably, whilst the tool provides a useful set of goal-areas, little is known about the way in which caregivers select from these to generate unique goals and factors that influence their selections. Since goal formation would occur within the context of early engagement and relationship development, consideration of these features requires further exploration.

In this study we drew on PGPBS (Fox and Emerson 2010) and other relevant measures to develop a new method of goal selection and investigate its use with caregivers of children with IDD. The study had two main aims: Firstly, to examine the utility of a novel method for supporting caregiver goal selection, that if helpful, could be used as part of future clinical pathways. This aim principally focussed on whether caregiver preferences and goals for PBS could be identified via the method. The second aim was to investigate psychological and emotional processes involved in how caregivers identified goals, together with their needs and experiences at this time of early engagement. In line with these aims, we report on goal-areas identified by caregivers and themes that arose during the process of generating these to inform research and clinical practice concerning both PBS and goal selection more broadly.

Method

Participants

Participants (10 females, 2 males) were parents/guardians of children with IDD and BTC awaiting service support. Participants 4a and 4b were from the same family and interviewed together. Participants’ children were 4–15 years, diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC) and/or intellectual disability (ID). Caregivers identified a range of BTCs that their child displayed at the time of recruitment Table 1.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted via a National Research Ethics Service committee in South-East England with Research Sponsorship provided by the University of Kent. Participants were recruited primarily from two Learning Disability (ID) CAMHS teams, sent information packs, given an opportunity to discuss the study and asked to return consent forms.

Interviews (90 min) were arranged at times/places convenient to participants, audio-recorded and transcribed in anonymous form. All participants received a summary report detailing goals/priorities they had generated to support future engagement with services and professionals.

We used interviews, based on a semi-structured protocol and card selection procedure, to support and explore caregiver goals in relation to five key areas: Quality of Life (QoL) for caregivers and their family; QoL for their child; BTC for their child; adaptive behaviors for their child and positive and negative aspects of caregiver behavior.

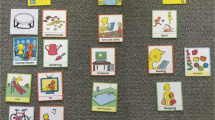

Each question area began with a card selection task in which participants chose from a range of word-based cards those of greatest relevance, concern or priority. Use of card selection to initiate interviews has previously been effectively employed in research with families of children with IDD (Mitchell and Sloper 2003) and to identify valued life domains in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Flaxman et al. 2013; Hayes et al. 1999).

In our study, card selection was facilitated through Talking Mats (TM) (Murphy 1998); an augmentative communication tool that enables people to organise and express their views. TMs are typically used with people with communication difficulties and involve placement of visual symbols to indicate thoughts or feelings. Our use of TMs, using written stimuli with language competent adults was novel. The method was chosen due to its potential to prompt and record in-depth discussions in a manner that could be openly shared and explored with caregivers.

Separate mats were used for each question area, divided into three columns that provided a scale of frequency, concern, or priority/value. Following card placements, participants were invited to select goals/priorities for future support. For instance, participants were asked to sort cards relating to different types of BTC and then identify behaviors they would most like to change for their child.

Card-stimuli included items from PGPBS, supplemented by a range of further sources including items from family QoL (Hoffman et al. 2006), child behavior (Goodman 1997), and parenting-style questionnaires (Arnold et al. 1993). Overall, eight items were covered in each of the first 2two mats corresponding to QoL domains for caregivers and their child; 22 during both the third and fourth mats corresponding to BTC and adaptive behavior for children; and 24 during mats relating to positive and negative caregiver behaviors. Blank cards were also always provided so that responses were not restricted. A complete list of stimuli is available upon request from the first author.

After each mat, follow-up questions were used to explore the area further and the processes that influenced items selected. In a small number of instances, it was not possible to complete all TMs (corresponding areas were however still covered in discussion). Within this process, the interviewer endeavoured to be mindful of the emotional needs of participants, to provide a non-judgemental, supportive context for discussions and maintain a close working relationship.

Data Analysis

A Framework Approach (Ritchie and Spencer 1994) was used for analysis. During data-management stages, transcripts were read multiple times by the first author who noted initial themes and categories with the structure of the interview (using NVivo software). In-vivo codes relating to each question area and broader discussions were generated. Emergent themes were recorded in an index table for each question, with quotations and examples listed accordingly. During the second, descriptive-accounts stage, transcripts were re-examined to identify overlap between themes and seek further supporting evidence for these, ensuring those that remained were grounded in data and captured participants’ experience. Finally, associations and patterns between themes were investigated (the exploratory accounts stage).

Results

Overall, two themes emerged during discussions of goal selection concerning caregiver/family QOL (“Being realistic” and “Most important”); two in relation to children’s QOL (“What’s going on?” and “Getting perspective”); three in relation to BTC (“Does do that,” “Just naughty children” and “For us it’s negative”); two in relation to children’s adaptive behavior (“Has it in him” and “Good at that”) and four in relation to caregiver’s own behavior (“Did that right,” “End of my tether,” “A kind of spiral” and “What’s needed”).

QoL for Caregivers and Family

Being realistic

All participants identified priorities for personal/family QoL that included interpersonal-relationships (10 participants), social-inclusion (five participants) self-determination (five participants), physical-health (nine participants), emotional-wellbeing (seven participants), personal-development (six participants), rights (six participants), and material-wellbeing (eight participants). There was considerable variation between what was/was not considered an important goal-area between families. Final placements were personal and varied:

Rights respected, Hmm, this is what I deem important first, yes absolutely (Participant-9)

Rights being respected (laughing) I couldn’t give a shit what other people think! (Participant-1).

The processes by which final placements were made were psychologically complex. Initial choices typically reflected what participants perceived as possible given current circumstances and prior experiences; selecting what might be considered ‘realistic’ rather than what was of greatest value. Early placements were often made with hesitation that referenced poor support and complexity of child needs and behavior.

Being invited to lots of birthday parties once upon a time would have been something I would have wanted and expected but now it’s being realistic and that’s beyond something he could really cope with (Participant-10).

The interviewer respected all items initially placed by participants but also attempted to communicate an appreciation of current circumstances and explore the potential of these to influence what was selected.

That is very understandable. It seems where you placed that area really reflects how difficult things are. But I get the feeling there is some sadness or frustration? That in an ideal world you might want something different? (Researcher).

As interviews progressed, caregivers made increasingly fine-grained discriminations, to clarify QoL domains of greatest importance, often changing selections accordingly and contacting emotions of sadness or frustration:

This one for how actually is and here for how would want it to be (eight)

We never go out together and that is important. That’s gone and has changed our lives dramatically. A massive, massive loss. (Participant-11)

Most important

In the later discussions concerning this mat participants increasingly reflected on items in accordance with their personal/fundamental value and meaning.

Personal development, that’s what life is all about really isn’t it and in amongst all the bad things that have happened to us I have a little niche. (Participant-3)

At these times significance of domains was commonly linked to aspiration for caregivers and their family, expressed with a sense of vitality. Caregivers highlighted what they wanted to happen, rather than what they had previously experienced or considered possible.

Everyone in family accessing and being part of and included in things, just because he’s got a disability I don’t feel we should be excluded from anything I don’t think he should have to fit in necessarily with everyone else, why should he, why can’t they adapt why has he got to change? (Participant-2)

QoL for Children

What’s going on?

QoL priorities caregivers identified for their child, spanned interpersonal-relationships (eight participants), social-inclusion (four participants) self-determination (six participants), physical-health (seven participants), emotional-wellbeing (six participants), personal-development (seven participants), rights (seven participants), and material-wellbeing (four participants). As with the initial mat, inviting caregivers to reflect on areas of importance for their child required exploration (though for different reasons) and was often met with initial uncertainty.

She does see things differently to how we see them, and she puts things into perspective differently and it is quite hard to figure out what’s going on up there. (Particpant-4a).

A useful strategy, initiated by one caregiver when reflecting on these items (and utilised in subsequent interviews), focused on discriminating areas perceived as important for a child’s life based on the caregiver’s understanding of their needs and those based on the child’s own preferences/desires:

I would say she enjoys it but doesn’t understand the significance and importance of it so these things are all the things that are hugely important to her but she doesn’t know (Particpant-3).

Getting perspective

Through further discussion, caregivers were able to identify areas of importance and demonstrated meaningful ways to attune with their child’s perspective. An increasingly empathic stance flowed well from earlier discussions regarding areas of importance for caregivers’ own lives and often provided fresh insights into a child’s needs and aspirations:

Actually because in some ways she does like to be in, to have things a certain way, and in certain places and times and I suppose that is actually about her feeling in control of certain situations and so actually thinking about it I would bring that there. (Participant-9).

BTC for Child

Does do that

Participants readily identified and discussed BTC displayed by their child and appeared to find the TM structure helpful in this regard:

It’s reassuring actually because you have created a list of several challenging behaviors and when you see ones she does you obviously feel there are other children doing those things as well. (Participant-9).

Just naughty children

Impact of supporting a child with BTC was poignant and participants recounted many negative experiences with services, the public, and family that had caused lasting upset and pain:

Sometimes I’m in tears when we’re at home and I’m thinking I wish we had of gone but my husband’s saying you know what you’d have been like – would have been on edge. (Participant-2).

Another mum turned round and called him an effing little retard in my hearing. I cried for a week (Participant-5).

For us it’s negative

Final goals selected by caregivers were varied but included a focus on verbal behaviors like screaming/shouting (participants 1, 2 and 5,); physical aggression (participants 2, 6, 7, 9 and 11); self-injury (participants 7, 8 and 11), and tantrums or other/idiosyncratic behaviors (participants 2, 3, 5 and 10).

Whilst some variation was attributable to individual differences in children’s behavior, goals typically corresponded to the impact a given behavior had on QoL areas caregivers had prioritised. Goals to reduce frequency/severity of a behavior, were linked to positive impacts predicted for both family and child QoL if even small reductions could be achieved:

Even if we could move it [BTC] to half the table, at least I could put some of the green [QoL] things back on. (Participant-3).

Not get into that escalation point where he’s trying to scratch or kick you, his life would improve dramatically, and so would ours. (Participant-11).

Adaptive Behavior for Child

Has it in him

Participants seemed to find discussion of strengths and challenges within the same interview helpful, and a contrast to other discourses surrounding their child:

It’s always what the child isn’t doing or does badly, they don’t say, like when you pick them up from school its always like he hit this child or he didn’t go to assembly. Not he spent this long in assembly or he did this today and everything, I don’t get any of that I always get the bad point. (Participant-2).

Good at that

Considering both strengths and difficulties in adaptive behavior seemed to enrich caregiver’s understanding of the needs and potential of their child. For some this involved, expanding or reframing

Struggling to understand, just make sense of life, but of course he can’t make sense of life because of his autism, so I do understand, but it’s hard. (Participant-6).

For others, reflecting on positive aspects of their child’s behavior gave voice to a more balanced and hopeful perspective:

And as much as it’s difficult with him doing all this touching I am proud of how he is and that he’s loving and smiley most the time. (Participant-8).

Participants often appeared re-energised and motivated when identifying these behaviors/characteristics and the interviewer was able to share in the joy and enthusiasm that was generated:

Friendly, very, right up there. We went for a swimming lesson and the bloke said he’s very sociable isn’t he?! Wanted to say hello to everyone in the pool. That’s his main strength being friendly (Participant-2).

We’re seeing real progress she’s able to put a toothbrush into her mouth and able to spoon-feed. (Participant-9).

That’s incredible, so important to be aware of that as something to build on! (Researcher).

Final adaptive behavior goals were strategic in nature and linked closely to prior elements of the interview. These included a focus on coping skills (participants 1, 3, 4, 8, 10 and 11); skills to support independence (participants 2, 7 and 9), and social-interaction (participants 1, 2, 3, 5, 6). Participants described with optimism how support in chosen areas could build upon a child’s strengths or emergent skills, maximise QoL and/or reduce BTC:

We could sit at a table and have a meal, if we do that that’s bringing a family component into her life so she’s going to feel safe because knows a family that loves her and that would build the relationships in turn (Participant-3).

If relationships and understanding for sharing then it would deal with his need to take it out on her or whatever and so her relationship with him would be better because she wouldn’t feel that scared of him so then maybe she would share better as well herself and it all goes round full circle (Participant-7).

Caregiver Behaviors

Did that right

Building upon prior discussions, caregivers highlighted a range of positive parenting practices they engaged in

He loves watching me cook and he got the masher out the drawer and one of those moments and he started mashing for me and I got him to hold it and that and all off his own back (Participant-11).

At these times participants reflected on relationships between their own positive parenting, prevention of children’s BTC, and development of adaptive behavior:

I’ll help a bit and give him encouragement and motivation and talk to him with respect, you can avoid it. (Participant-5).

The more you do take him out really the more you extinguish that kind of need. I do see a link between the two, the more you can give him those experiences the less there seems to be the need [for BTC]. (Participant-10).

As with adaptive behavior, caregivers emphasised opportunities to highlight their own strengths to be refreshing and empowering:

You think “yes I’ve done something right” because an ASD child never tells you when you’re doing something well. (Participant-1)

End of my tether

Subsequently, caregivers were also able to talk about less helpful parenting behaviors. Participants did this openly and appeared to find the structure of the mat and the development of a trusting relationship with the interviewer helpful:

I do shout when at the end of my tether, when gone on all day and I’m like I’ve had enough now and “stop it!” (Participant-2).

Horrible feeling but that completely broke my heart and made me feel awful and I certainly haven’t said it to many people but just couldn’t be around him. (Participant-7)

A kind of spiral

Participants often identified interrelationships between their behavior and that of their child. Here, episodes of BTC both increased the likelihood parents acted with an authoritarian style and decreased the likelihood they could engage in positive practices.

I can remember doing it because he got into this kind of spiral. (Participant-10).

When child just full of rage and not responding to you it does all go pear shaped and wave arms about and end up threatening and that’s definitely the biggest. (Participant-7).

I will shout at him but sometimes shouting doesn’t work because that’s why he shouts back. (Participant-6).

For some, these responses evidently arose in the context of broader demands and stresses of caring in an unsupportive community:

So she started pulling their hair and the child got very upset, as did the mother of course, because she wouldn’t let go of her hair, and then we became negative with her because we were in front of other people and you want to be seen to be taking a stand. (Participant-9)

Finally, whilst noting factors that influenced interactions with their child, participants often observed in heartfelt ways disparity between the value they associated with previously identified life areas and aspects of their own behavior:

The others are not huge emotional expenses for me but I don’t want to shout or argue with her, I end up feeling shit afterwards. Why should I be arguing and shouting at a 12-year old? I don’t want to do that (Participant-3).

What’s needed?

The impact of these interactions, QoL and wellbeing was salient within discussions that ultimately informed meaningful goal selection. Particular goals for changing unhelpful caregiver behavior included a focus on shouting, losing temper/arguing with their child (participants, 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7); restraining or ignoring their child (participant 9), and letting their child ‘have whatever they want’ (participant 1).

Caregivers also selected goals based on positive parenting practices they currently used less often or experienced difficulty using, including engaging in preferred/new/individual activities with their child (participants 1, 2, 7 and 9); finding new ways to support/communicate with their child (participants 1, 3, 6 and 9), and listening or being more patient towards their child (participants 4 and 5). These goals were grounded in consideration of other QoL goals and aspirations for their child’s development, with caregivers evidencing rich insight into relationships between all of these:

Goal might be to spend a happy hour at a children’s birthday party, you almost need to break down what are the things that are required to have that success? And talk about that. Those kinds of conversations I find really useful. What’s needed coz then you feel successful because you’ve only set yourself up for that. (Participant-9)

Discussion

In this study, we interviewed caregivers of children with IDD and BTC to identify personalised support goals reflective of a PBS framework and explore processes by which these were formed. A TM-interview approach was used to provide a structured and comprehensive framework for consideration of goal-areas and ensure close attention to interpersonal interactions.

A qualitative approach supported the exploratory aims of the study and allowed the richness of accounts and process to be captured. As a first study using the TM method in this way, there were however inevitably some limitations. Firstly, participants represented a subset of families, who whilst demonstrating considerable need, were able and motivated to engage in interviews. Care needs to be taken in generalisation of findings to different families in different situations. Secondly, whilst the study demonstrated an effective method to help caregivers identify personally meaningful goals, utility and effectiveness of using these within a clinical pathway remains to be tested.

Participant’s children presented with a range of BTC and as in prior research (Herring et al. 2006; Griffith and Hastings 2014), impact of this on QoL and wellbeing for caregivers was evident. Family-focused research emphasises centrality of relationship building throughout clinical encounters (Brotherson et al. 2010; Dunst et al. 1994) and this was experienced as critical within interviews. Here, use of TMs and an emotionally-sensitive dialogue helped not only prompt consideration of goal-areas but normalised areas of difficulty, setting the scene for a non-judgemental, enquiring discussion.

Ultimately, when supported in this way, all participants were able to select goals that could inform future assessment, intervention, and outcome monitoring. The TM-interview approach therefore appeared a helpful method for facilitating goal identification and may have good utility as part of a PBS pathway. The diversity of goals/priorities identified spanned the majority of domains included by Fox and Emerson (2010) but also reflected additional items included for each starter mat. Importantly, caregivers’ goals were conceptually coherent (relating to interplay of several maintaining factors), strategic (focussed on discrete changes to generate multiple positive changes), and high in social validity (related closely to change in areas of personal importance/worth).

Complex psychosocial contexts, together with biological factors and interactions between individuals, their environment and those who support them, are at the heart of conceptual models of BTC in PBS (Hastings et al. 2013). It was therefore of note that caregivers were able to openly discuss and identify interconnections between their own behavior, behavior of their child, and other social and contextual variables. Notably, these insights informed goal selection, were obtainable within a first meeting, and could be constructed and elaborated during a relatively brief interview. The fact that caregivers can generate hypotheses of this nature as part of goal selection (when a supportive framework is used) highlights both their expertise and the potential to draw on this more routinely as part of early engagement in clinical practice.

Enhancing motivation and empowering caregivers to facilitate future change also appeared to be a strength of the TM-interview approach. In addition to a focus on valued life areas, caregivers welcomed the opportunity to discuss and appreciate strengths of their child, successful parenting behavior and the connection between these and desired outcomes. Caregivers appeared to find this alternative to problem saturated discussions helpful and evidenced a constructional approach to goal selection as a result.

In conclusion, goal-selection is a fundamental process to supporting treatment effectiveness and stakeholder engagement. Whilst goal-selection has been studied and advocated for within general mental health literature for children and families it has previously received little attention within the context of PBS and children with IDD. The TM-interview structure used in the current study highlighted the strengths and processes of engaging with caregivers of children with particularly complex needs to form personally meaningful goals and has good potential to support effective partnership working in applied settings.

References

Arnold, D. S., O’Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S., & Acker, M. M. (1993). The parenting scale: a measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 137–144.

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. (1968). Current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91–7.

Baker, B. L., McIntyre, I. I., Blacher, J., Crnic, K., Edelbrock, C., & Low, C. (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: behavior problems and parenting stress overtime. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(4), 217–230.

Brotherson, M. J., Summers, J. A., Naig, L. A., Kyzar, K., Friend, A., Epley, P., Gotto, G. S., & Turnbull, A. P. (2010). Partnership patterns: addressing emotional needs in early intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 30(1), 32–45.

Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., & Sailor, W., et al. (2002). Positive behavior support: evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4, 4–16.

Carr, E. G. (2007). The expanding vision of positive behavior support: research perspectives on happiness, helpfulness, hopefulness. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9(1), 3–14.

Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2009). Positive behavior support and early intervention. In W. Sailor, G. Dunlap, G. Sugai & R. Horner (Eds.), Handbook of positive behavior support. New York: Springer.

Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2007). Parent-professional partnerships: a valuable context for addressing challenging behaviors. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 54(3), 273–285.

Dunlap, G., Carr, E. G., Horner, R. H., Zarcone, J. R., & Schwartz, I. (2008). Positive behavior support and applied behavior analysis: a familial alliance. Behavior Modification, 32(5), 682–698.

Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Johanson, C. (1994). Parent-professional collaboration and partnerships. In C. J. Dunst, C. M. Trivette & A. G. Deal (Eds.), Supporting and strengthening families: Vol 1. Methods, strategies and practices (pp. 197–211). Cambridge: Brookline Books.

Durand, V. M., Hieneman, M., Clarke, S., Wang, M., & Rinaldi, M. L. (2012). Positive family intervention for severe challenging behavior 1: a multisite randomized clinical trial. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(3), 133–143.

Edbrooke-Childs, J., Jacob, J., Law, D., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2015). Interpreting standardized and idiographic outcome measures in CAMHS: what does change mean and how does it relate to functioning and experience? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(3), 142–148.

Emerson, E., & Einfeld, S. (2011). Challenging behavior. (3rd ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Emerson, E. (1995). Challenging behaviour: Analysis and intervention in people with severe intellectual disabilities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flaxman, P. E., Bond, F. W., & Livheim, F. (2013). The mindful and effective employee: An Acceptance & Commitment Therapy training manual for improving well-being and performance. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Fox, P., & Emerson, E. (2001). Socially valid outcomes of intervention for people with mental retardation and challenging behavior: views of different stakeholders. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3(3), 183–189.

Fox, P., & Emerson, E. (2010). Positive goals for Positive Behavioral Support: Interventions to improve quality of life for people with learning disabilities whose behavior challenges. Brighton: Pavilion Press.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Gore, N., et al. (2013). Definition and scope for positive behavioral support. International Journal of Positive Behavioral Support, 3, 14–23.

Gore, N., Hastings, R., & Brady, S. (2014). Early intervention for children with learning disabilities: making use of what we know. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 19(4), 181–189.

Griffith, G. M., & Hastings, R. P. (2014). He’s hard work but he’s worth it: the experience of caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities and challenging behavior: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27, 401–419.

Hastings, R., et al. (2013). A conceptual framework for understanding why challenging behaviors occur in people with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Positive Behavioral Support, 3, 5–13.

Hastings, R. P. (2002). Parental stress and behavior problems of children with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(3), 149–160.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Herring, S., Gray, K., Taffe, J., Tonge, B., Sweeney, D., & Eninfeld, S. (2006). Behavior and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: associations with parental mental health and family functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 874–882.

Hoffman, L., Marquis, J., Poston, D., Summers, J. A., & Turnbull, A. (2006). Assessing family outcomes: psychometric evaluation of the Beach Centre Family Quality of Life Scale. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 1069–1083.

Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., & Koegel, R. L., et al. (1990). Toward a technology of ‘nonaversive’ behavioral support. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 15(3), 125–32.

Jacob, J., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Holley, S., Law, D., & Wolpert, M. (2016). Horses for courses? A qualitative exploration of goals formulated in mental health settings by young people, parents and clinicians. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 21(2), 208–223.

Kincaid, D., & Fox, L. (2002). Person-Centred Planning and Positive Behavior Support. In S. Holburn, B. Mount, (Eds.) Person-Centred Planning: research, practice and future directions. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Kincaid, D., Dunlap, G., Kern, L., Lane, K. L., Bambara, L. M., Brown, F., Fox, L., & Knoster, T. P. (2016). Positive behavior support: A proposal for updating and refining the definition. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(2), 69–73.

Law, D. (2011). Goals and goal based outcomes (GBOs): Some useful information (Version 2.0). London: CAMHS Press.

Lucyshyn, J. M., Albin, R. W., & Nixon, C. D. (1997). Embedding comprehensive behavioral support in family ecology: an experimental single-case analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 241–251.

McLaughlin, T. W., Denney, M. K., Snyder, P. A., & Welsh, J. L. (2012). Behavior support interventions implemented by families of young children: examination of contextual fit. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(2), 87–97.

Mitchell, W., & Sloper, P. (2003). Quality indicators: disabled children’s and parents’ prioritizations and experiences of quality criteria when using different types of support services. British Journal of Social Work, 33, 1063–1080.

Murphy, J. (1998). Helping people with severe communication difficulties to express their views: a low-tech tool. Communication Matters, 12, 9–11.

Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. G. Burgess (Eds.), Analyizing qualitative data (pp. 172–94). London: Routledge.

Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., Berridge, D. M., & Lancaster, G. A. (2011a). Behavior problems at five years of age and maternal mental health in autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(8), 1137–1147.

Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., Lancaster, G. A., & Berridge, D. M. (2011b). A population-based investigation of behavioral and emotional problems and maternal mental health: associations with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 91–99.

Wolpert, M., Ford, T., Trustmam, E., Law, D., Deighton, J., Flannery, H., & Fugard, R. J. B. (2012). Patient-reported outcomes in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS): use of idiographic and standardized measures. Journal of Mental Health, 21(2), 165–173.

Woodman, A. C., Mawdsley, H. P., & Hauser-Cram, P. (2015). Parenting stress and child behavior problems within families of children with developmental disabilities: transactional relations across 15 years. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 264–276.

Acknowledgements

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (DRF-2015-08-196) The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author contributions

N.J.G.: conceived the study, led on design, data collection, analysis and writing of manuscript. P.M.: Supported study design, contributed towards writing and editing of final manuscript. R.P.H.: Supported study design, contributed towards writing and editing of final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted by London and Harrow Research Ethics Committee (REC ref 16/LO/04546) with Research Sponsorship provide by the University of Kent.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gore, N.J., McGill, P. & Hastings, R.P. Making it Meaningful: Caregiver Goal Selection in Positive Behavioral Support. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1703–1712 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01398-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01398-5