Abstract

Women and men differ in their tastes for the performing arts. Gender differences have been shown to persist after accounting for socioeconomic factors. This paper uses this difference to shed light on how decisions on arts consumption are made in households. Based on relatively recent theoretical developments in the literature on household decision-making, we use three different so-called distribution factors to show for the first time that the relative bargaining power of spouses affects their arts consumption. Using a sample from the US Current Population Survey, which includes data on the frequency of visits to cultural activities, we regress attendance on a range of socioeconomic variables using a count data model. The distribution factors consistently affect attendance by men at events such as the opera, ballet and other dance performances, which are more frequently attended by women than by men. We conclude that when men have more bargaining power, they tend to attend such events less frequently.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A large literature has investigated the determinants of demand for high cultural activities and a wide range of variables have been considered as drivers of this demand. Beyond income, education, childhood exposure to the arts, family background and time constraints, authors have also looked at social drivers including influence from spouses and unmarried partners.

One aspect that has to our knowledge not been investigated is the role of intra-household bargaining. This phenomenon has received considerable attention in household economics with the advent of powerful recent methodological innovations that have allowed authors to peak into the black-box of intra-household allocations (see Chiappori and Donni 2009 for an introduction).

Many important decisions that are of interest to researchers are made not by individuals but by households and couples. Though it is impossible to understand how exactly these decisions are made, especially since each household may have different and complex dynamics, some simple concepts should apply to a large enough number to be detected statistically. The idea is simple enough. When couples of men and women (or by extension any group of people) have to make a decision jointly, two things should matter: Their individual preferences and their relative influence within the couple. This relative influence comes under many names such as bargaining weight, bargaining power or empowerment.

An argument could be made, that the consumption of high culture does not fit into the category of household consumption, since it takes place outside the home and is not necessarily purchased jointly. But we argue that such decisions are not generally made independently by household members for two reasons. First, couples in particular exhibit preferences for joint leisure with considerable consumption externalities within the household. Second, households face joint constraints in time and money.Footnote 1

This study investigates whether relative bargaining power matters in households’ and cohabitating individuals’ demand for activities such as the opera, theater and dance performances. We do this by including so-called distribution factors in regressions on attendance. These are variables which can be considered relevant to bargaining power but unrelated to individual preferences, such as the husband’s share in a couple’s income.

This analysis is made possible by the existence of systematic differences between men and women in high cultural consumption. Such differences in demand have been observed across countries and over decades. Gender differences in high cultural participation persist after controlling for educational level, occupation, age, family status, residential status and income (Bihagen and Katz-Gerro 2000; Katz-Gerro and Jæger 2015).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature regarding both demands for cultural consumption and bargaining models of the household. The methodology and data used are described in Sect. 3, results are discussed in Sect. 4 and the last section concludes.

2 Review of the literature

Two very distinct strands of literature are relevant to this paper and the two are explored separately below. The first part summarizes the literature on cultural consumption, in particular on the estimation of demand and drivers of attendance and participation. The second gives a short introduction to the literature on collective models of the household, which have seen rising popularity in household economics and development economics but have not yet been applied to the demand for cultural consumption.

2.1 Demand for the arts

A large literature exists that analyses the composition of cultural audiences and the determinants of attendance at high cultural events. An early sociological literature, dominated by the theory of social reproduction (Bourdieu 1973, 1984) has already made a fundamental observation that has proven robust across time, types of performing arts activities and countries: High cultural consumption is especially prevalent among the elites (Seaman 2006; Falk and Katz-Gerro 2016).

Consequently, two types of variables are strongly associated with attendance at high cultural events: Income and educational attainment. For Bourdieu, this fits neatly into a theory that saw high culture as more than merely a leisurely pursuit for the wealthy but as a factor in perpetuating class divisions and justifying class-based discrimination. This latter part of the theory has proved difficult to test empirically; however, and the focus has since shifted to the more mundane estimation of demand for the high arts.

Later research has, however, tried to shed light into the question of whether a taste for the high arts is indeed inherited along with wealth and has frequently found significant effects for measures of childhood and adolescent exposure to the arts (Kracman 1996) as well as for measures of parental wealth and education (Nagel and Ganzeboom 2002).

Factors such as age, sexual orientation (Lewis and Seaman 2004) and ethnic background (Ateca-Amestoy 2008) have also been included in studies of cultural consumption and age in particular is a much used control variable as it is readily available in survey data. In the absence of panel data, age could be thought to proxy the dynamics of intertemporal consumption choices as well as cohort effects. Though models of intertemporal consumption dynamics are not unique to the literature on consumption of high culture, mechanisms such as habit formation (Taylor and Houthakker 2009), learning by consuming (Lévy-Garboua and Montmarquette 1996) or rational addiction (Stigler and Becker 1977; Gary and Becker 1988) are seen as particularly important for this type of consumption. But these intertemporal models do not in fact make clear predictions about the relationship between age and consumption. Age also does not seem to play a consistent role in the empirical literature.

Another class of variables that have been included in demand estimation in the arts relates to time constraints. Since attendance at performing arts events is time consuming, factors such as hours worked or the number of children in the household should be important drivers of cultural consumption.Footnote 2 The impact of time constraints may in turn also depend on the value of time, i.e., wages (Borgonovi 2004). Nonetheless, results in this area have been mixed (Katz-Gerro and Jæger 2015; Ateca-Amestoy 2008, 2010).

A relatively large literature exists that has investigated elasticities of demand to prices (see Seaman (2005) for examples), a difficult enterprise since quality is hard to measure in the sector.Footnote 3 While many studies have found demand to be inelastic on average (Zieba 2009; Throsby 1994), some note that this can vary, others even find elasticities below -1 (Lévy-Garboua and Montmarquette 1996).

Beyond prices, one supply side variable that is both consistently found to matter and is relatively easy to obtain is the location of households. Those who live in urban centers are much more likely to attend than those who live in rural areas for obvious reasons (Frateschi and Lazzaro 2008). More detailed measures of the cultural offer in the vicinity of a household’s residence are hard to come by and rarely used.

Gender differences have been found to exist in the consumption of high culture in many studies. A common observation is simply that women are more likely to attend high-brow cultural events than men. This difference persists after controlling for such factors as income, education, professional status, age and family status (Bihagen and Katz-Gerro 2000), suggesting that it may be either the result of robust differences in socialization between men and women or of a suggested household division of cultural labor (Christin 2012; DiMaggio and Mukhtar 2004).Footnote 4

Perhaps surprisingly these differences in preferences by gender do not seem to have declined over time. DiMaggio and Mukhtar (2004) find that they have remained constant in the US since the early 80s despite the fact that popular explanations of the phenomenon refer to gender roles which one might expect to have declined in importance.

Joint consumption and consumption externalities are also important factors since people often attend cultural events in groups and exchange opinions and experiences with one another. This is particularly relevant for the present study as the data under consideration consists of couples, married and unmarried. Upright (2004) as well as Lazzaro and Frateschi (2017), Frateschi and Lazzaro (2008) focus on couples and find that partners’ attributes, such as education, are strongly associated with an individual’s arts attendance. These factors are so important in fact, that they rival one’s own attributes.

This can be explained in two ways: Since a partner’s attributes are an indication of their preferences, we may on the one hand be observing correlations between married people’s tastes either due to convergence during marriage or due to marital sorting on unobserved correlates of taste for the arts.Footnote 5 On the other hand, it is also likely that married people bargain and compromise in order to attend cultural events together. Just to remove any lingering doubt anyone may have, Kalmijn and Bernasco (2001) find evidence that indeed both married and unmarried partners spend a considerable amount of time on joint leisure activities.

While considering the importance of a spouse’s (or a partner’s) preferences, it seems obvious that one’s spouse’s time constraints may also matter. This is investigated in Kraaykamp et al. (2008) and Lazzaro and Frateschi (2017). Both allow not only for direct dependence of attendance on spouse’s working arrangement but also distinguish between situations where both partners attended a type of event and situations where only one did. Data on actual joint attendance are rare and "both attended" does not automatically imply joint attendance in either study. But the authors of the latter have detailed timing of attendance, meaning that they can tell when spouses attended the same kind of event at the same time.

2.2 Collective models

The consideration of joint consumption of cultural events and the arts naturally leads to the question of how couples make such decisions when their preferences differ. Luckily, there is an extensive literature on decision-making in households.

In early models, the household has been seen as a single decision maker that maximizes a "household utility function" under total income and time constraints (e.g., Becker 1965, 1991). This model, which has proven to be versatile and easy to use many applications, is now often referred to as the unitary model.

But the idea that the unitary model is not adequate in all situations and that households should be modeled as consisting of multiple persons whose nonidentical preferences lead to conflict and compromise has been around for a long time. Bargaining models do this. These models fall broadly into the categories of noncooperative and cooperative models. The latter have proved more popular. While early contributions applied Nash-bargaining (Manser and Brown 1980; McElroy and Horney 1981), these have since been supplanted by the simpler and rather versatile collective model (Chiappori 1992). This model has been successful partly because it does not actually specify a bargaining process that the household is assumed to follow. Instead, it is only assumed that whatever decision-making process is at work, leads to Pareto efficient outcomes.

A simple collective model of the household incorporating the consumption of the arts may take the following form. Suppose a household consists of members 1 and 2 and that member j’s separable utility function for arts consumption is given by \(U_j(a, b)\), where a and b are "artistic goods." Suppose that member 1 likes a more than does member 2 and vice versa for good b. The collective household problem then takes the form

under a joint budget constraint, where y is household income and p is prices. In other words, a weighted sum of the members’ utilities is maximized. Consumption of the goods a and b will depend on this weight \( \mu \), which in turn may depend on income, prices and on a variable D affecting the distribution of influence within the couple. Prices and income are also part of the budget constraint, but D is not. It only influences this decision problem through the bargaining weight \(\mu\). This means that demand for a can be expressed as

and the demand for b is of the same form. Equation (2) is a structural representation of the demand equations that are estimated in this paper, with D playing a special role in detecting the presence of intra-household bargaining. Simply put, if it affects demand at all, it must do so through the bargaining weight \(\mu\) and therefore \(\mu\) must matter in determining demand.

Candidates for such a distributional variable must be plausibly unrelated to personal preferences but related to bargaining power within the household. These variables are known as distribution factors (Browning et al. 1994) and their relevance to decision-making outcomes are a key piece of evidence in favor of bargaining models more generally. The most popular distribution factors relate to the source of household income. For instance, the husband’s share of total income (unlike, say, his hours worked) should not matter in consumption decisions except by influencing his relative bargaining position.

In fact, a large body of evidence has by now been accumulated that shows that the distribution of income among the household members does affect outcomes. A notable example is Lundberg et al. (1997), who found that a policy change in the 1970s which designated women as the recipients of child allowances instead of men induced a marked change in consumption behavior in affected households.

Variables that are not directly related to the source of household income have also been used as distribution factors. These include relative wages, control over land, the "marriage market environment" (Bourguignon et al. 2009)Footnote 6 as well as demographic characteristics such as the difference between the spouses in age (Cherchye et al. 2012) and educational level (Vermeulen et al. 2006). In each case, if the indicator is in, say, the wife’s favor (i.e., for instance, the male-female age difference is large and negative), then her bargaining power in the household will tend to be higher, ceteris paribus.

Beyond their use in the structural estimation of full-fledged collective models, distribution factors have also become a very popular ingredient in more standard demand systems to assess whether or not the members’ relative bargaining position plays an important role in determining outcomes. In the present paper, we follow this approach and include three different distribution factors in a state of the art model of demand for the arts. These are the husband’s income share, the difference in age between the spouses and the difference in educational levels between the spouses.

3 Data and methodology

3.1 Data

The data for this study come from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA) which is conducted by the National Endowment for the Arts, an agency of the US federal government. The two most recent available waves, 2008 and 2012, are pooled for this study in order to maximize the sample size while assuring comparability of definitions.

A major advantage of this survey is that it is conducted as part of the Current Population Survey, an extensive data gathering effort by the Census Bureau which allows supplements. This permits the merger of SPPA data with other data collected in the same context. Here, the two waves of SPPA data are merged with the respective datasets of the Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement, resulting in a combined dataset with information on such diverse variables as hours worked and opera attendance for the same individuals. It should be noted that not all SPPA households were also included in the ASEC and vice versa, resulting in the loss of some observations.

The resulting two combined SPPA/ASEC waves for 2008 and 2012 were then transformed from individual to household level and merged into a pooled final dataset for this analysis. No two households were present in both waves. Income data were adjusted for inflation between 2008 and 2012 and is thus given in (log) 2012 US dollars.

In order to obtain a complete and homogeneous sample for this study, households were selected which consisted of one couple of a man and a woman with any number of children and for which both cultural attendance and individual income data were available. Some are dropped when control variables were missing, resulting in a final sample of 3271 couples out of 11800 households in the original sample. Though they need not be married, most (92.4%) are and we will henceforth refer to them as husbands and wives.

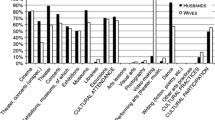

Female and male attendance at cultural activities. Bars show the number of men (gray) or women (white) in our sample of 3271 couples who visited a given number of times, irrespectively of whether they went alone or together. Persons who attended zero times are omitted in these graphs (color figure online)

Cultural consumption Figure 1 shows distributions of the attendance variables for men and women, combinations of which are later regressed on observables. The graphs show only the frequencies of positive attendance numbers, leaving out those who attended a given activity zero times. Large numbers of zeros are common for arts attendance. For instance, Ateca-Amestoy (2010) see no attendance at any dance or theater event over the course of a month for \(95\%\) of respondents in Spanish data.

Our numbers do not distinguish between visits undertaken alone or with a partner. Though these are count data, mean annual attendance is close to one only for visits to museums or galleries, indicating the large number of men and women for each of the nine categories who have not attended at all in the past year.

Another point that is already clear from Fig. 1 is the imbalance between men and women in the selected sample: Women in these couples attend all activities more frequently than men. Nonetheless, this gender difference is not the same across activities.Footnote 7

Table 1 gives a closer look at the difference between men and women by category. For each category of activities, the first two columns show the mean annual attendance rates and the third gives the deviation in percent of the men’s attendance rate from that of women. These relative differences range from the marginal such as in jazz music, Latin and salsa performances and museum visits to pronounced over-representation of women in ballet, live dance and opera. The last column gives p values for a null hypothesis of no difference from a paired two-sample t test. These follow a similar pattern as the relative differences in attendance.

Though not reported here, patterns in attendance of singles are remarkably similar, with the same three activities being attended by men most frequently in relative terms. On the other end, the most female-dominated activities among singles are the Ballet, live Dance and Musicals. All but one of these also feature on the bottom of Table 1.

Exploiting precisely this difference, the three abovementioned categories with only marginal gender differences in attendance will be grouped to form the class of non-gendered activities and the three categories with strong female over-representation will be grouped together as female-dominated activities. The sums of attendances in each of these two classes will be the dependent variables for the regressions performed in Sect. 4.

Summary statistics for the two classes are given in Table 2. The difference in overall attendance is largely driven by museum visits which are included in the non-gendered activities and which represent by far the most popular category of cultural activities. The female-dominated activities on the other hand are particularly high-brow and have very low mean attendance from both men and women. Despite such differences in overall attendance the female-dominated and the non-gendered activities still behave similarly and both present a very large amount of zeros.

Explanatory variables Tables 3 and 4 show descriptions and sample breakdowns of the explanatory variables used in this study. These variables fall into three categories. The distribution factors "income share," "age difference" and "education difference" which are the variables of interest, are in a category of their own and shown in Table 4. The income share is based on a personal income aggregate constructed from detailed questions on various sources of income which is available in the ASEC supplement. It is defined as the share of a couple’s combined income that is earned or received by the man. As shown in the table, this number is larger than 0.5 in a majority of cases. Age difference is the difference in years between the husband’s and the wife’s ages, and education difference is the difference between the husband’s and the wife’s educational levels on a six point scale.Footnote 8 Note that this difference is negative whenever the wife’s value exceeds that of the husband.

Individual characteristics form the second category. These are age, educational attainment and hours worked, all of which are measured separately for men and women.Footnote 9 To allow for a flexible relationship between age and cultural consumption, this variable is coded as a set of three dummy variables that indicate roughly, young, middle aged and older individuals. This coding also reduces the potential for multicollinearity with the distribution factor "age difference," which is defined as the difference in years. Educational attainment is similarly coded as a dummy that indicates any level of attainment equivalent to or higher than a full university-level Bachelor’s degree. The weekly number of hours worked, however, will enter the regression equations linearly.

The last category of variables consists of those at the level of the household. These include household income and urban residence. Household income, as mentioned earlier, is given in 2012 USD and enters the model in logs, as is common practice in household demand estimation. The urban residence dummy indicates whether the household is situated in any of the metropolitan areas (Core-Based Statistical Areas, CBSA) which are used by the US Census Bureau. This variable is meant to capture the availability of cultural activities in the vicinity of the household and is thus the only explanatory variable on the supply side.

For each household, only one adult member was asked to complete the survey, reporting on his or her own attendance as well as their partner’s. Though men and women are roughly equally likely to be the respondent, there is a weak correlation with the income share and own-reported attendance in particular of men is slightly higher than when reported by the spouse. For these reasons, we include a dummy for the survey respondent in the regressions below.

3.2 Methodology

The aim of the analysis is to test whether the distribution of resources within the household matters for decisions on cultural consumption. The dependent variable will the number of visits to one of the two classes of cultural activities per year as described in Sect. 3.1.Footnote 10 This section describes the regression model for the results presented later.

In the model, cultural consumption by an individual in a couple may be driven by four groups of factors: Own characteristics, household characteristics, partner’s characteristics and distribution factors. The inclusion of partner’s characteristics is based on earlier research (Upright 2004; Lazzaro and Frateschi 2017) in the field of cultural consumption whereas the inclusion of distribution factors, which are meant to proxy the relative influence of one partner in a couple, is based on the literature on bargaining in household decision-making. A simple generalized linear model with those characteristics is given by Eq. 3.

where \(V_{h,i}\) is the number of visits in a given year to some category or class of cultural activities such as the opera by person i in household h. The expected value of this number in the above model is a function of a linear index in a range of characteristics of the individual \(X_{h,i}\), the spouse \(X_{h,j}\) and the household \(Z_h\) as well as in the distribution factor \(D_h\). \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\) and \(\delta\) are parameters to be estimated.

The inverse link function \(\psi ^{-1}\) describes how the linear index maps into expected attendance rates. In the simplest case, \(\psi\) is the identity which would result in an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. It is easy to see why this would be inappropriate in the case considered here: The dependent variable V can for instance never be negative, but will (very) often be equal to zero, if the individual has not attended the given class of activities at all. In this situation, OLS will lead to negative predicted values for many individuals.

The specification of the above model is therefore not immediately obvious. Despite its evident shortcomings, the OLS estimator has been used in similar situations by other authors (e.g., Kraaykamp et al. (2008) who strictly speaking use ordered rather than count data). Others have decided to transform the dependent variable into a dummy, giving one for any positive number of attendances and zero otherwise. This allows the use of binary choice models such as logit (Borgonovi 2004) but it would imply the loss of a considerable amount of information in the data in the case of this study.

The true nature of the dependent variables is that of count data, i.e., the number of attendances may equal any integer or zero and has therefore no upper bound as would be the case in ordered choice scenarios. Three different count data specifications were considered for the job: The Poisson model, which uses the link function \(\psi (x) = \ln (x)\), is the most restrictive, followed by the negative binomial and the zero-inflated negative binomial. The latter is the most general of these models, being essentially a combination of a binary choice model and a regular negative binomial of which in turn the Poisson model is a special case.

Among the count data specifications mentioned, the preferred model is the zero-inflated negative binomial. This choice is based on two statistical tests that provide clear results: The Vuong (1989) test as implemented in Stata generates a test statistic based on the likelihood-ratio and favors the zero-inflated negative binomial over the standard negative binomial model on balance. This can be seen as a test of the presence of excess zeros in the dependent variables, that is, a higher number of zeros than predicted by a properly fitted negative binomial distribution. Because the test was not significant in all cases, we report an alternative negative binomial specification in Table 8 in the appendix, showing that results remain very similar.

Another more standard likelihood ratio test is performed to test the zero-inflated negative binomial model against the null that a zero-inflated Poisson model is instead appropriate. The latter is nested in the former and essentially requires that the non-inflated part have a variance equal to the mean. In contrast, the zero-inflated negative binomial allows for larger (but not smaller) variance. Thus, this test can be seen as a test of over-dispersion with respect to the Poisson model and the results are very clearly in favor of the negative binomial version in all cases with all p values below \(1\%\).

The zero-inflated negative binomial model, which provides the best fit to the data, has a two-stage interpretation. This is related to the "zero-inflation," the part where a binary choice model determines excess zeros. In this first stage, it is determined whether an individual will certainly not attend, or whether it is possible that she will attend. The second stage then determines the number of attendances for those for whom attendance was not excluded in the first stage. This number of attendances may still equal zero. We interpret the first stage as relating to the individual’s ability to attend arts events as distinct from her preference for doing so.Footnote 11 Therefore, only variables that affect one’s ability to attend are included in the first stage, while variables related to preferences are added in the second stage.

Since we have multiple distribution factors at our disposal, we can also perform a test of the collective model. When a collective household is composed of two decision makers, any distribution factors can affect demand only through the bargaining weight \(\mu\) (see Eq. (2)). But this bargaining weight is one-dimensional. For this reason, conditionally on any preference shifters (X and Z above), the effects of two distribution factors on the demand for any one good must be in the same proportion to one another as they are in the demand for any other good. Such proportionality tests (Browning and Chiappori 1998) were performed for the present analysis. Across specifications, these resulted in non-rejections of the condition implied by the collective model.

4 Results and analysis

Estimation results from the models described in Sect. 3.2 are discussed here. Table 5 shows results for the zero-inflated negative binomial regression on our most reliable distribution factor, men’s share in household income. Table 6 shows results from the regression on the difference in age between the partners and Table 7, those from the regression on the difference in educational level.

Each contains four columns for regressions on four different dependent variables. The first column is for the number of visits by women at activities that are female dominated as defined in the previous section, the second is for attendance by men at the same type of activities and so forth. As described in Sect. 3.1, the two classes of activities are based on the observation that while none of the activity categories are dominated by male attendees, some are roughly similar in popularity between men and some are attended much more frequently by women than by men.

All coefficients are reported in their exponentiated form in order to allow an interpretation as incidence rate ratios (IRRFootnote 12). Therefore, coefficients smaller than one imply a predicted decrease in attendance with a rise in the explanatory variable.

Since standard errors are likely to be correlated across the four equations, they are obtained using seemingly unrelated estimation. Based on these, p values are reported in parentheses after each exponentiated coefficient and stars indicate significance levels. The number of observations used in the regressions is slightly lower in Table 5 than in Tables 6 and 7 because our "classic" distribution factor, income share, was computed using individual income data and is missing for some of the observations for which the remaining explanatory variables are available.

Some very clear results are unsurprising. This is especially true for the significantly positive effects of both own educational attainment and partner’s educational attainment. Upright (2004), Lazzaro and Frateschi (2017) also find this, including the fact that own and partner’s attributes had similar effects.

Two other non-surprises come from the urban dummy and from household income. Both clearly tend to increase the expected number of attendances. The income result is very common in the literature (e.g., Bihagen and Katz-Gerro (2000); Borgonovi (2004) and many others), while urban households have often, but not always been found to attend more (e.g., Frateschi and Lazzaro (2008)).

The role of these two variables in the zero-inflated negative binomial regressions may need some explaining. These two were used in the inflation part of the model, that is, before these and any other factors can influence the expected number of visits, these two determine whether there will be even the possibility of a positive number of visits.Footnote 13 Confusingly, the signs are reversed here: A coefficient smaller than one means that the probability of observing a sure zero is reduced. The impact of both variables is therefore consistent with what would be intuitively expected.

The role of age is not the same in different types of activities, though there is a pattern whereby the young age effect is significantly smaller for women than for men in non-gendered events. As discussed in Sect. 2.1, the development of arts consumption over one’s lifetime is thought to be subject to intertemporal dynamics and age effects have not been consistent in the literature. While Bihagen and Katz-Gerro (2000) find negative signs for age, the variable is insignificant, sometimes positive or nonlinear in Katz-Gerro and Jæger (2015), Frateschi and Lazzaro (2008), Ateca-Amestoy (2010) respectively.

The hours worked variable should give some indication of available spare time. Though the signs of the associated coefficients are almost always negative and thus consistent with this interpretation, the measured impact is perhaps not as large as expected.Footnote 14 An interaction term that was added to account for cross-dependence of the effects of hours worked on partner’s time constraints is also rarely significant, perhaps reflecting simply that time constraints are not particularly important. Where it is significant though, the sign is positive, suggesting that the effect of time constraints is weakened when the partner is also time constrained.

The most important results are those related to the distribution factors, the man’s income share in the household (Table 5), the difference in age between partners (Table 6) and the difference in educational attainment (Table 7). The associated coefficients very clearly tend to be negative across the board. In fact, they are consistently negative in the regressions using our most important distribution factor, the income share. This indicates a reduction in the number of visits by either member for an increase in the distribution factor, which is always defined in such a way that larger values point to a better bargaining position for the husband. Though this variable is not significant for attendance by women at female-dominated events or for men at non-gendered activities, it is an important factor in men’s attendance at female-dominated high culture events. This result holds true for all three distribution factors.

Across models, men are less likely to attend such activities if their share in household income is larger. Since this result is conditional on individual attributes and especially on time constraints, this strongly indicates a role of bargaining: Relatively more powerful men succeed in giving their preferences more weight and so in avoiding activities they do not care for. Using the interpretation of the coefficients as logs of incidence rate ratios (and thus of the exponentiated coefficients as incidence rate ratios, IRR), we can quantify the effects implied by the point estimates. For a shift of ten percent of household income from the wife to the husband, the expected IRR is \(\exp (\ln (0.256)/10) \approx 0.87\), implying an expected reduction by \(1-0.87 \approx 13\%\) in the number of visits by men to female-dominated activities. For an increase of one year in the age difference the estimated IRR is 0.963, or a \(4\%\) reduction and for an increase of one level in the difference in educational attainment the estimated IRR stands at 0.775, implying an expected reduction by \(22\%\) in the number of visits by the husband to female-dominated activities.

A caveat should be added to the results displayed in Tables 6 and 7 where the distribution factors were constructed from information that also enters control variables in the same regression. Though the regressors are not collinear, these relationships do seem to affect the coefficients on the age and education covariates.

The result concerning the impact of the income share on attendance by men at female-dominated activities is especially striking in light of the strong effect of household income. If higher income makes an individual more likely to attend any of the classes of activities studied here, then whichever member of the household has higher income may be thought to want to attend more ceteris paribus. But this effect from intra-household inequality is not controlled for in the above regressions as income is considered only at the household level. Therefore, the effect of the income share measured here can be considered conservative, as the part of the bargaining-related effect that persists after any countervailing income effect from intra-household inequality.

5 Conclusion

This paper has explored the role of household decision-making in individual arts consumption. In addition to considering partners’ as well as own characteristics, we tested whether the distribution of resources within the household plays a role in determining individual cultural behavior. This amounts to including a distribution factor, such as the share of household income generated by the husband, in a model of demand for the arts.

As the literature has usually found, own education and partner’s educational level are good predictors of cultural attendance. Unsurprisingly, household income and urban residence also have a positive effect on participation in cultural activities.

The most relevant result concerns the importance of the distribution factor in art consumption choices. When men’s share of household income is larger the probability of men’s attendance at female-dominated high culture events decreases, even conditionally on total household income, hours worked and a host of other controls. We find analogous effects for the difference in age between husbands and wives as well as for the difference in educational attainment, both of which variables are also commonly used as distribution factors by other authors. While similar results have been found in the literature on bargaining models of household decision-making, this is the first such test concerning consumption of the arts.

Our results open the door to several interesting questions. Among them is the question of how they relate to children’s arts exposure and the transmission of culture. In addition, while this paper has taken a static approach, the bargaining effects found here may be part of intertemporal choices by members of couples. This angle has already been recognized as important in the demand for the arts and could benefit from a consideration of intra-household bargaining.

Notes

To see how important joint constraints are consider an example: A wife’s evening at the local jazz club is of concern to her husband since it will oblige him to spend the evening taking care of the children. At the same time, she is spending money that will not be available for the next family vacation. Time and money constraints are not independent here since the couple may hire a babysitter at additional expense.

Age is also likely indicative of time constraints, as mid-career parents will tend to be more pressed for time than retirees.

Other attempts to explain the difference in high-brow cultural consumption between men and women have been made. For instance, Lizardo (2006) suggests that it is caused by a difference in relative importance of cultural knowledge in the professional environments of men and women.

Although marital sorting on observed characteristics will also produce such correlations, the effect would be netted out by controlling for own observed attributes.

This typically refers to local sex ratios, which affect the ease with which a new partner could be found.

Though the question of why these patterns arise may be interesting, it is beyond the scope of this paper.

1: less than high school, 2: high school, 3: some college—no degree, 4: associate degree, 5: bachelor’s degree, 6: postgraduate degree.

As is typical of American data, a "race" variable was available but was not included in the results as preliminary regressions showed that it was consistently not significant. Childhood exposure to the arts and arts education was available for only a small subsample and was therefore not included in order to preserve the sample size which was especially important for the relatively complex zero-inflated negative binomial.

Additionally, the appendix contains results from regressions on attendance in each of the nine categories of cultural activities.

Such a two-stage conception of decisions on arts consumption and participation also shows up in the Heckman-selection models used e.g., in Lévy-Garboua and Montmarquette (1996) and Lazzaro and Frateschi (2017). While the latter investigates time use, which is continuous, a count data model is more appropriate in the present analysis.

This means that a coefficient of 2 can be interpreted as indicating that an increase in the explanatory variable by one unit is associated with a twofold increase in the expected value of the dependent variable; A coefficient of 0.66 means that an increase in the explanatory variable by one unit is associated with a decrease in the expected value of the dependent variable of one third.

In choosing these two variables for the logit part of the model, we are essentially proposing a mechanism for the generation of the excess zeros. Some individuals simply do not have the possibility either for financial or geographic reasons to engage in a given type of cultural consumption. Only those who can attend will then make decisions about how often to do so (and may still choose to attend zero times).

We are not alone in not finding strong results here (see Borgonovi 2004)

References

Ateca-Amestoy, V. (2008). Determining heterogeneous behavior for theater attendance. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32(2), 127–151.

Ateca-Amestoy, V. (2010). Cultural participation patterns: evidence from the Spanish time use survey. In ESA Research Network Sociology of Culture Midterm Conference: Culture and the Making of Worlds.

Becker, G. S. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal, 75, 493–517.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard.

Bihagen, E., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2000). Culture consumption in Sweden: The stability of gender differences. Poetics, 27(5), 327–349.

Borgonovi, F. (2004). Performing arts attendance: an economic approach. Applied Economics, 36(17), 1871–1885.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. London: Tavistock, 178.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bourguignon, F., Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. A. (2009). Efficient intra-household allocations and distribution factors: Implications and identification. The Review of Economic Studies, 76(2), 503–528.

Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. A. (1998). Efficient intra-household allocations: A general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica, 66(6), 1241–1278.

Browning, M., Bourguignon, F., Chiappori, P. A., & Lechene, V. (1994). Income and outcomes: A structural model of intrahousehold allocation. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1067–1096.

Cherchye, L., De Rock, B., & Vermeulen, F. (2012). Married with children: A collective labor supply model with detailed time use and intrahousehold expenditure information. The American Economic Review, 102(7), 3377–3405.

Chiappori, P. A. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100(3), 437–467.

Chiappori, PA., & Donni, O. (2009). Non-unitary models of household behavior: A survey of the literature. IZA Discussion Papers.

Christin, A. (2012). Gender and highbrow cultural participation in the United States. Poetics, 40(5), 423–443.

DiMaggio, P., & Mukhtar, T. (2004). Arts participation as cultural capital in the United States, 1982–2002: Signs of decline? Poetics, 32(2), 169–194.

Falk, M., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2016). Cultural participation in Europe: Can we identify common determinants? Journal of Cultural Economics, 40(2), 127–162.

Frateschi, C., & Lazzaro, E. (2008). Attendance to cultural events and spousal influences: the Italian case. “Marco Fanno” Working Paper N 84, University of Padua.

Gary, S., & Becker, K. M. M. (1988). A theory of rational addiction. Journal of Political Economy, 96(4), 675–700.

Kalmijn, M., & Bernasco, W. (2001). Joint and separated lifestyles in couple relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(3), 639–654.

Katz-Gerro, T., & Jæger, M. M. (2015). Does women’s preference for highbrow leisure begin in the family? Comparing leisure participation among brothers and sisters. Leisure Sciences, 37(5), 415–430.

Kraaykamp, G., van Gils, W., & Ultee, W. (2008). Cultural participation and time restrictions: Explaining the frequency of individual and joint cultural visits. Poetics, 36(4), 316–332.

Kracman, K. (1996). The effect of school-based arts instruction on attendance at museums and the performing arts. Poetics, 24(2), 203–218.

Lazzaro, E., & Frateschi, C. (2017). Couples’ arts participation: Assessing individual and joint time use. Journal of Cultural Economics, 41, 47–69.

Lévy-Garboua, L., & Montmarquette, C. (1996). A microeconometric study of theatre demand. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20(1), 25–50.

Lewis, G. B., & Seaman, B. A. (2004). Sexual orientation and demand for the arts. Social Science Quarterly, 85(3), 523–538.

Lizardo, O. (2006). The puzzle of women’s highbrow culture consumption: Integrating gender and work into Bourdieu’s class theory of taste. Poetics, 34(1), 1–23.

Lundberg, S. J., Pollak, R. A., & Wales, T. J. (1997). Do husbands and wives pool their resources? evidence from the United Kingdom child benefit. The Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), 463–480.

Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and household decision-making: A bargaining analysis. International Economic Review, 21(1), 31–44.

McElroy, M. B., & Horney, M. J. (1981). Nash-bargained household decisions: Toward a generalization of the theory of demand. International Economic Review, 22(2), 333–349.

Nagel, I., & Ganzeboom, H. B. (2002). Participation in legitimate culture: Family and school effects from adolescence to adulthood. The Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences, 38(2), 102–120.

Seaman, BA. (2005). Attendance and public participation in the performing arts: A review of the empirical literature. Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research Paper Series (06–25).

Seaman, B. A. (2006). Empirical studies of demand for the performing arts. Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, 1, 415–472.

Stigler, G. J., & Becker, G. S. (1977). De gustibus non est disputandum. The American Economic Review, 67(2), 76–90.

Taylor, L. D., & Houthakker, H. S. (2009). Consumer demand in the United States: Prices, income, and consumption behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

Throsby, D. (1994). The production and consumption of the arts: A view of cultural economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(1), 1–29.

Upright, C. B. (2004). Social capital and cultural participation: Spousal influences on attendance at arts events. Poetics, 32(2), 129–143.

Vermeulen, F., Bargain, O., Beblo, M., Beninger, D., Blundell, R., Carrasco, R., et al. (2006). Collective models of labor supply with nonconvex budget sets and nonparticipation: A calibration approach. Review of Economics of the Household, 4(2), 113–127.

Vuong, Q. H. (1989). Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica, 57(2), 307–333.

Zieba, M. (2009). Full-income and price elasticities of demand for German public theatre. Journal of Cultural Economics, 33(2), 85–108.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 8 shows results of a regression similar to that reported in Table 5. The difference is in the link function chosen. Instead of a zero-inflated negative binomial, here a negative binomial model was used. This model is reported here as a robustness check. Notably, the effect of the distribution factor on attendance at female-dominated events remains significant and very similar in magnitude, still implying the same \(4\%\) reduction in the number of visits per year for a \(10\%\) shift in income in favor of the husband.

Table 9, which comes in two parts, shows results for regressions on attendance by either member of the couple for each of the nine activities available in the data. This allows for comparisons of individual attendance across activities. Unfortunately, the effects of the distribution factor are much harder to detect here, both because visits by both members of the household are considered and because there are very few nonzero observations for some of the activities. This results in a lack of variation in the dependent variable on which to base the estimation. Especially Latin and salsa performances, the opera and ballet are attended so rarely overall that inference becomes difficult. For the same reason, inclusion of state fixed effects becomes hard here, and they are omitted.

The income share variable is significant at the 1% level only once, for jazz music, and though the sign is consistent with the previous result that relatively wealthier men depress attendance in all categories, there is no particular reason why this effect should be strong for jazz and not for the others. Again, the relatively small numbers of nonzero observations may not be sufficient to see through the noise here.

Other effects are strong enough though, to be detected in the majority of categories. These are the usual suspects, log income and education. Log income very consistently reduces the probability of never going in the inflate part of the models. The fact that this variable has this prominent role in determining who does and does not go at all limits the interpretability of its coefficient in the main part of the model, where it is found significant only in the case of classical music. Theoretically, this means that higher income increases the probability of going at least once per year while decreasing the expected number of attendances among those who have the means.

Education, both of the man and the woman, has a similarly consistent role. The associated coefficients are mostly significant, greater than one whenever they are significant and often very large. One exception to this rule is the Latin and Salsa category, which is unusual in other ways also. This may be partly due to the fact that though it is performance art, it is less high-brow in character than most of the other activities. But again, the oddity may also be the result of the small number of nonzero observations (or of the omission of a variable indicating Hispanic origin, which may be important for this category but not for the others).

The effects of education are especially strong for very high-brow activities such as classical music, the opera and dance performances, where the latter two are especially influenced by female and male education, respectively.

Another trend that is relatively consistent comes from the dummy for data from the year 2012, the second wave considered here. Coefficients are mostly below one, indicating a negative trend in the number of visits across activities.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mauri, C.A., Wolf, A.F. Battle of the ballet household decisions on arts consumption. J Cult Econ 45, 359–383 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-020-09395-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-020-09395-z