Abstract

Purpose

To explore whether the risks of early- or late-onset preeclampsia vary among frozen embryo transfer (FET) with different regimens for endometrial preparation and fresh embryo transfer (FreET).

Methods

We retrospectively included a total of 24129 women who achieved singleton delivery during their first cycles of in vitro fertilization (IVF) between January 2012 and March 2020. The risks of early- and late-onset preeclampsia after FET with endometrial preparation by natural ovulation cycles (FET-NC) or by artificial cycles (FET-AC) were compared to that after FreET.

Results

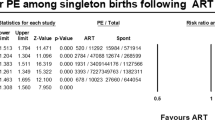

After adjustment via multivariable logistic regression, the total risk of preeclampsia was higher in the FET-AC group compared to the FreET group [2.2% vs. 0.9%; adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 2.00; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.45–2.76] and FET-NC group (2.2% vs. 0.9%; aOR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.59–2.96).When stratified by the gestational age at delivery based on < 34 weeks or ≥ 34 weeks, the risk of late-onset preeclampsia remained higher in the FET-AC group than that in the and FreET group (1.8% vs. 0.6%; aOR: 2.56; 95% CI: 1.83–3.58) and the FET-NC group (1.8% vs. 0.6%; aOR: 2.63; 95% CI: 1.86–3.73). We did not find a statistically significant difference in the risk of early-onset preeclampsia among the three groups.

Conclusions

An artificial regimen for endometrial preparation was more associated with an increased risk of late-onset preeclampsia after FET. Given that FET-AC is widely used in clinical practice, the potential maternal risk factors for late-onset preeclampsia when using the FET-AC regimen should be further explored, considering the maternal origin of late-onset preeclampsia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The corresponding authors can be contacted on reasonable data request.

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C. Clinical rationale for cryopreservation of entire embryo cohorts in lieu of fresh transfer. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.018.

Chen ZJ, Shi Y, Sun Y, Zhang B, Liang X, Cao Y, et al. Fresh versus frozen embryos for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):523–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1513873.

Wei D, Liu JY, Sun Y, Shi Y, Zhang B, Liu JQ, et al. Frozen versus fresh single blastocyst transfer in ovulatory women: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10178):1310–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32843-5.

Sites CK, Wilson D, Barsky M, Bernson D, Bernstein IM, Boulet S, et al. Embryo cryopreservation and preeclampsia risk. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(5):784–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.08.035.

Ginstrom Ernstad E, Wennerholm UB, Khatibi A, Petzold M, Bergh C. Neonatal and maternal outcome after frozen embryo transfer: increased risks in programmed cycles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):126 e1-e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.010.

Jing S, Li XF, Zhang S, Gong F, Lu G, Lin G. Increased pregnancy complications following frozen-thawed embryo transfer during an artificial cycle. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36(5):925–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-019-01420-1.

Zaat TR, Brink AJ, de Bruin JP, Goddijn M, Broekmans FJM, Cohlen BJ, et al. Increased obstetric and neonatal risks in artificial cycles for frozen embryo transfers? Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42(5):919–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.01.015.

Hu KL, Zhang D, Li R. Endometrium preparation and perinatal outcomes in women undergoing single-blastocyst transfer in frozen cycles. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(6):1487–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.12.016.

Saito K, Kuwahara A, Ishikawa T, Morisaki N, Miyado M, Miyado K, et al. Endometrial preparation methods for frozen-thawed embryo transfer are associated with altered risks of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placenta accreta, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(8):1567–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dez079.

Asserhoj LL, Spangmose AL, Aaris Henningsen AK, Clausen TD, Ziebe S, Jensen RB, et al. Adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes in 1,136 singleton pregnancies conceived after programmed frozen embryo transfer (FET) compared with natural cycle FET. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(4):947–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.10.039.

Wang Z, Liu H, Song H, Li X, Jiang J, Sheng Y, et al. Increased risk of pre-eclampsia after frozen-thawed embryo transfer in programming cycles. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00104.

Zong L, Liu P, Zhou L, Wei D, Ding L, Qin Y. Increased risk of maternal and neonatal complications in hormone replacement therapy cycles in frozen embryo transfer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020;18(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-020-00601-3.

Barsky M, St Marie P, Rahil T, Markenson GR, Sites CK. Are perinatal outcomes affected by blastocyst vitrification and warming? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):603 e1-e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.002.

Makhijani R, Bartels C, Godiwala P, Bartolucci A, Nulsen J, Grow D, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in programmed versus natural vitrified-warmed blastocyst transfer cycles. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41(2):300–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.03.009.

Busnelli A, Schirripa I, Fedele F, Bulfoni A, Levi-Setti PE. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes following programmed compared to natural frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deac073.

Li C, He YC, Xu JJ, Wang Y, Liu H, Duan CC, et al. Perinatal outcomes of neonates born from different endometrial preparation protocols after frozen embryo transfer: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03791-9.

Roelens C, Blockeel C. Impact of different endometrial preparation protocols before frozen embryo transfer on pregnancy outcomes: a review. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(5):820–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.09.003.

Bortoletto P, Prabhu M, Baker VL. Association between programmed frozen embryo transfer and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(5):839–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.07.025.

Garovic VD, Dechend R, Easterling T, Karumanchi SA, McMurtry Baird S, Magee LA, et al. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis, blood pressure goals, and pharmacotherapy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2022;79(2):e21–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/hyp.0000000000000208.

Phipps E, Prasanna D, Brima W, Jim B. Preeclampsia: updates in pathogenesis, definitions, and guidelines. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(6):1102–13. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.12081115.

Burton GJ, Redman CW, Roberts JM, Moffett A. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ. 2019;366:l2381. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2381.

Roberts JM, Rich-Edwards JW, McElrath TF, Garmire L, Myatt L, Global pregnancy C. Subtypes of preeclampsia: recognition and determining clinical usefulness. Hypertension. 2021;77(5):1430–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14781.

Raymond D, Peterson E. A critical review of early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66(8):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0b013e3182331028.

Staff AC, Redman CWG. The differences between early- and late-onset pre-eclampsia. In: Saito S, editor. Preeclampsia: basic, genomic, and clinical. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2018. p. 157–72.

Staff AC. The two-stage placental model of preeclampsia: an update. J Reprod Immunol. 2019;134–135:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2019.07.004.

Pereira MM, Mainigi M, Strauss JF. Secretory products of the corpus luteum and preeclampsia. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(4):651–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmab003.

Conrad KP, Petersen JW, Chi YY, Zhai X, Li M, Chiu KH, et al. Maternal cardiovascular dysregulation during early pregnancy after in vitro fertilization cycles in the absence of a corpus luteum. Hypertension. 2019;74(3):705–15. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13015.

von Versen-Hoynck F, Schaub AM, Chi YY, Chiu KH, Liu J, Lingis M, et al. Increased preeclampsia risk and reduced aortic compliance with in vitro fertilization cycles in the absence of a corpus luteum. Hypertension. 2019;73(3):640–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12043.

von Versen-Hoynck F, Narasimhan P, Selamet Tierney ES, Martinez N, Conrad KP, Baker VL, et al. Absent or excessive corpus luteum number is associated with altered maternal vascular health in early pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73(3):680–90. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12046.

Tay J, Foo L, Masini G, Bennett PR, McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB, et al. Early and late preeclampsia are characterized by high cardiac output, but in the presence of fetal growth restriction, cardiac output is low: insights from a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(5):517.e1-e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.007.

Masini G, Foo LF, Tay J, Wilkinson IB, Valensise H, Gyselaers W, et al. Preeclampsia has two phenotypes which require different treatment strategies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2s):S1006–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.052.

Puissant F, Van Rysselberge M, Barlow P, Deweze J, Leroy F. Embryo scoring as a prognostic tool in IVF treatment. Hum Reprod. 1987;2(8):705–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136618.

Gardner DK, Lane M, Schoolcraft WB. Physiology and culture of the human blastocyst. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;55(1–2):85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00136-x.

Webster K, Fishburn S, Maresh M, Findlay SC, Chappell LC. Diagnosis and management of hypertension in pregnancy: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2019;366:l5119. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5119.

Poon LC, Shennan A, Hyett JA, Kapur A, Hadar E, Divakar H, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on pre-eclampsia: a pragmatic guide for first-trimester screening and prevention. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;145(Suppl 1):1–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12802.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No 579: Definition of term pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1139–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000437385.88715.4a

Luke B, Brown MB, Eisenberg ML, Callan C, Botting BJ, Pacey A, et al. In vitro fertilization and risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: associations with treatment parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(4):350 e1-e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.003.

Engle WA, Tomashek KM, Wallman C. “Late-preterm” infants: a population at risk. Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1390–401. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2952.

Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta. 2009;30(6):473–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2009.02.009.

Ogge G, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Hussein Y, Kusanovic JP, Yeo L, et al. Placental lesions associated with maternal underperfusion are more frequent in early-onset than in late-onset preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2011;39(6):641–52. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm.2011.098.

Sebire NJ, Goldin RD, Regan L. Term preeclampsia is associated with minimal histopathological placental features regardless of clinical severity. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(2):117–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/014436105400041396.

Guo F, Zhang B, Yang H, Fu Y, Wang Y, Huang J, et al. Systemic transcriptome comparison between early- and late-onset pre-eclampsia shows distinct pathology and novel biomarkers. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(2):e12968. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.12968.

Ren Z, Gao Y, Gao Y, Liang G, Chen Q, Jiang S, et al. Distinct placental molecular processes associated with early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Theranostics. 2021;11(10):5028–44. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.56141.

Conrad KP. Maternal vasodilation in pregnancy: the emerging role of relaxin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301(2):R267–75. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00156.2011.

Post Uiterweer ED, Koster MPH, Jeyabalan A, Kuc S, Siljee JE, Stewart DR, et al. Circulating pregnancy hormone relaxin as a first trimester biomarker for preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;22:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2020.07.008.

Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376(9741):631–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60279-6.

Staff AC, Benton SJ, von Dadelszen P, Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Powers RW, et al. Redefining preeclampsia using placenta-derived biomarkers. Hypertension. 2013;61(5):932–42. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.111.00250.

Umapathy A, Chamley LW, James JL. Reconciling the distinct roles of angiogenic/anti-angiogenic factors in the placenta and maternal circulation of normal and pathological pregnancies. Angiogenesis. 2020;23(2):105–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-019-09694-w.

Conrad KP, Graham GM, Chi YY, Zhai X, Li M, Williams RS, et al. Potential influence of the corpus luteum on circulating reproductive and volume regulatory hormones, angiogenic and immunoregulatory factors in pregnant women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;317(4):E677–85. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00225.2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 assisted reproductive technology fertility clinic and national summary report. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/art/reports/2019/fertility-clinic.html Accessed.

Wyns C, De Geyter C, Calhaz-Jorge C, Kupka MS, Motrenko T, Smeenk J, et al. ART in Europe, 2018: results generated from European registries by ESHRE. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(3):hoac022. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoac022.

Garovic VD, White WM, Vaughan L, Saiki M, Parashuram S, Garcia-Valencia O, et al. Incidence and long-term outcomes of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2323–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.028.

Palomba S, de Wilde MA, Falbo A, Koster MP, La Sala GB, Fauser BC. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(5):575–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv029.

Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, de Groot CJM, Hofmeyr GJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):999–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00070-7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and staff of the Center for Reproductive Medicine of Shandong University for their cooperation and support.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071718 and 82101784).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.W., Y.L., and Z.J.C. supervised the entire study, including the procedures, conception, design, and completion; Y.N., L.S., and D.Y.Z. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; Y.N., L.S., D.Y.Z., Y.H.W., R.L.M., J.L.Z., and X.W.H. collected the data; D.M.W. and Y.L. revised the manuscript. All authors have been involved in interpreting the data and have approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Ethics Committee of the Center for Reproductive Medicine of Shandong University approved the study (Ethical Review No.04, 2022).

Consent to participate

Not application

Consent for publication

Not application

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, Y., Suo, L., Zhao, D. et al. Is artificial endometrial preparation more associated with early-onset or late-onset preeclampsia after frozen embryo transfer?. J Assist Reprod Genet 40, 1045–1054 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-023-02785-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-023-02785-0