Abstract

Purpose

This study tests whether metformin or diet supplement BR-DIM-induced AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) mediated effects on development are more pronounced in blastocysts or 2-cell mouse embryos.

Methods

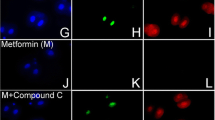

Culture mouse zygotes to two-cell embryos and test effects after 0.5–1 h AMPK agonists’ (e.g., Met, BR-DIM) exposure on AMPK-dependent ACCser79P phosphorylation and/or Oct4 by immunofluorescence. Culture morulae to blastocysts and test for increased ACCser79P, decreased Oct4 and for AMPK dependence by coculture with AMPK inhibitor compound C (CC). Test whether Met or BR-DIM decrease growth rates of morulae cultured to blastocyst by counting cells.

Result(s)

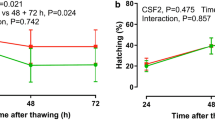

Aspirin, metformin, and hyperosmotic sorbitol increased pACC ser79P ~ 20-fold, and BR-DIM caused a ~ 30-fold increase over two-cell embryos cultured for 1 h in KSOMaa but only 3- to 6-fold increase in blastocysts. We previously showed that these stimuli decreased Oct4 40–85% in two-cell embryos that was ~ 60–90% reversible by coculture with AMPK inhibitor CC. However, Oct4 decreased only 30–50% in blastocysts, although reversibility of loss by CC was similar at both embryo stages. Met and BR-DIM previously caused a near-complete cell proliferation arrest in two-cell embryos and here Met caused lower CC-reversible growth decrease and AMPK-independent BR-DIM-induced blastocyst growth decrease.

Conclusion

Inducing drug or diet supplements decreased anabolism, growth, and stemness have a greater impact on AMPK-dependent processes in two-cell embryos compared to blastocysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Puscheck EE, Awonuga AO, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Rappolee DA. Molecular biology of the stress response in the early embryo and its stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;843:77–128.

Li Q, Yang Y, Louden E, Puscheck E, Rappolee D. High-throughput screens for embryonic stem cells; stress-forced potency-stemness loss enables toxicological assays. In: Faqi A, (eds) Developmental and reproductive toxicology. Methods in toxicology and pharmacology. 2016. Humana Press, New York, NY.

Bolnick A, Abdulhasan M, Kilburn B, Xie Y, Howard M, Andresen P, et al. Commonly used fertility drugs, a diet supplement, and stress force AMPK-dependent block of stemness and development in cultured mammalian embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1027–39.

Tang T, Lord JM, Norman RJ, Yasmin E, Balen AH. Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012.

Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ. Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327:951–3.

Rena G, Pearson ER, Sakamoto K. Molecular mechanism of action of metformin: old or new insights? Diabetologia. 2013;56:1898–906.

Duranteau L, Lefevre P, Jeandidier N, Simon T, Christin-Maitre S. Should physicians prescribe metformin to women with polycystic ovary syndrome PCOS? Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2010;71:25–7.

Palomba S, Pasquali R, Orio F Jr, Nestler JE. Clomiphene citrate, metformin or both as first-step approach in treating anovulatory infertility in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review of head-to-head randomized controlled studies and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;70:311–21.

Sinawat S, Buppasiri P, Lumbiganon P, Pattanittum P. Long versus short course treatment with metformin and clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction in women with PCOS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008.

Vane JR, Botting RM. The mechanism of action of aspirin. Thromb Res. 2003;110:255–8.

Jamal A, Milani F, Al-Yasin A. Evaluation of the effect of metformin and aspirin on utero placental circulation of pregnant women with PCOS. Iran J Reprod Med. 2012;10:265–70.

de Oliveira BC, Lanchote VL, de Jesus Antunes N, de Jesus Ponte Carvalho TM, Dantas Moises EC, Duarte G, et al. Metformin pharmacokinetics in nondiabetic pregnant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:1027–33.

Vause TD, Cheung AP, Sierra S, Claman P, Graham J, Guillemin JA, et al. Ovulation induction in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:495–502.

Jungheim ES, Odibo AO. Fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a decision analysis of different oral ovulation induction agents. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2659–64.

Genazzani AD, Ricchieri F, Lanzoni C. Use of metformin in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Women's Health (Lond Engl). 2010;6:577–93.

Palomba S, Falbo A, Russo T, Orio F, Tollino A, Zullo F. Role of metformin in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: the state of the art. Minerva Ginecol. 2008;60:77–82.

Escobar-Morreale HF. Polycystic ovary syndrome: treatment strategies and management. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2995–3008.

Moll E, van der Veen F, van Wely M. The role of metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:527–37.

Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, Carr BR, Diamond MP, Carson SA, et al. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:551–66.

Cheang KI, Sharma ST, Nestler JE. Is metformin a primary ovulatory agent in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:595–604.

Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–74.

Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, Walker KJ, et al. The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase. Science. 2012;336:918–22.

Higdon JV, Delage B, Williams DE, Dashwood RH. Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:224–36.

Le HT, Schaldach CM, Firestone GL, Bjeldanes LF. Plant-derived 3,3′-diindolylmethane is a strong androgen antagonist in human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21136–45.

Li Y, Li X, Guo B. Chemopreventive agent 3,3′-diindolylmethane selectively induces proteasomal degradation of class I histone deacetylases. Cancer Res. 2010;70:646–54.

Chen D, Banerjee S, Cui QC, Kong D, Sarkar FH, Dou QP. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) is associated with human prostate cancer cell death in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47186.

Rappolee DA. Impact of transient stress and stress enzymes on development. Dev Biol. 2007;304:1–8.

Mansouri L, Xie Y, Rappolee DA. Adaptive and pathogenic responses to stress by stem cells during development. Cell. 2012;1:1197–224.

Xie Y, Awonuga AO, Zhou S, Puscheck EE, Rappolee DA. Interpreting the stress response of early mammalian embryos and their stem cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;287:43–95.

Zhong W, Xie Y, Wang Y, Lewis J, Trostinskaia A, Wang F, et al. Use of hyperosmolar stress to measure stress-activated protein kinase activation and function in human HTR cells and mouse trophoblast stem cells. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:534–47.

Xie Y, Zhong W, Wang Y, Trostinskaia A, Wang F, Puscheck EE, et al. Using hyperosmolar stress to measure biologic and stress-activated protein kinase responses in preimplantation embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:473–81.

Hardie DG. Neither LKB1 nor AMPK are the direct targets of metformin. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:973. author reply 4-5

Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. The anti-diabetic drugs rosiglitazone and metformin stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase through distinct signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25226–32.

An Y, Sun Z, Li L, Zhang Y, Ji H. Relationship between psychological stress and reproductive outcome in women undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment: psychological and neurohormonal assessment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:35–41.

Hogan B, Beddington R, Constantini F, Lacy B. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2002.

Wang Y, Puscheck EE, Lewis JJ, Trostinskaia AB, Wang F, Rappolee DA. Increases in phosphorylation of SAPK/JNK and p38MAPK correlate negatively with mouse embryo development after culture in different media. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(Suppl 1):1144–54.

Bedaiwy MA, Miller KF, Goldberg JM, Nelson D, Falcone T. Effect of metformin on mouse embryo development. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1078–9.

Paltsev M, Kiselev V, Muyzhnek E, Drukh V, Kuznetsov I, Pchelintseva O. Comparative preclinical pharmacokinetics study of 3,3′-diindolylmethane formulations: is personalized treatment and targeted chemoprevention in the horizon? EPMA J. 2013;4:25.

Ross-Lee LM, Elms MJ, Cham BE, Bochner F, Bunce IH, Eadie MJ. Plasma levels of aspirin following effervescent and enteric coated tablets, and their effect on platelet function. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;23:545–51.

Yang Y, Jiang Z, Bolnick A, Dai J, Puscheck EE, Rappolee DA. Departure from optimal O2 level for mouse trophoblast stem cell proliferation and potency leads to most rapid AMPK activation. J Reprod Dev. 2016;

Xie Y, Awonuga A, Liu J, Rings E, Puscheck EE, Rappolee DA. Stress induces AMPK-dependent loss of potency factors Id2 and Cdx2 in early embryos and stem cells [corrected]. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1564–75.

Li Q, Gomez-Lopez N, Drewlo S, Sanchez-Rodriquez E, Dai J, Puscheck EE, et al. Development and validation of a Rex1-RFP potency activity reporter assay that quantifies stress-forced potency loss in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;

Slater JA, Zhou S, Puscheck EE, Rappolee DA. Stress-induced enzyme activation primes murine embryonic stem cells to differentiate toward the first extraembryonic lineage. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:3049–64.

Abdulhasan M, Li Q, Dai J, Abdul-Soud H, Puscheck E, Rappolee D. CoQ10 increases mitochondrial mass and polarization, ATP and Oct4 potency levels, and bovine oocyte MII during IVM while decreasing AMPK activity and oocyte death. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017; Accepted for publication..

Zhong W, Xie Y, Abdallah M, Awonuga AO, Slater JA, Sipahi L, et al. Cellular stress causes reversible, PRKAA1/2-, and proteasome-dependent ID2 protein loss in trophoblast stem cells. Reproduction. 2010;140:921–30.

Bertoldo MJ, Guibert E, Faure M, Rame C, Foretz M, Viollet B, et al. Specific deletion of AMP-activated protein kinase (alpha1AMPK) in murine oocytes alters junctional protein expression and mitochondrial physiology. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119680.

Mirouse V, Billaud M. The LKB1/AMPK polarity pathway. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:981–5.

Zhang L, Li J, Young LH, Caplan MJ. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates the assembly of epithelial tight junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17272–7.

Krawchuk D, Anani S, Honma-Yamanaka N, Polito S, Shafik M, Yamanaka Y. Loss of LKB1 leads to impaired epithelial integrity and cell extrusion in the early mouse embryo. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:1011–22.

Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, Baird DD, Schlatterer JP, Canfield RE, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:189–94.

Macklon NS, Geraedts JP, Fauser BC. Conception to ongoing pregnancy: the ‘black box’ of early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:333–43.

Secor E, Froment P, Louden E, Bolnick A, Yang Y, Abdulhasan M et al. (2017) AMPK agonists in diet supplements and Pharma mediate wide-ranging maternal and reproductive effects. eCAM. Submitted.

Tsou P, Zheng B, Hsu CH, Sasaki AT, Cantley LC. A fluorescent reporter of AMPK activity and cellular energy stress. Cell Metab. 2011;13:476–86.

Pauklin S, Vallier L. The cell-cycle state of stem cells determines cell fate propensity. Cell. 2013;155:135–47.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Erica Louden and Dr. Yu Yang for comments on the manuscript.

Funding

DAR and EEP from the Office of the Vice President for Research at Wayne State University and an R03 to DAR 1R03HD061431, from the REI fellows’ fund (AB), and from the funding of the Mary Iacobell and Kamran Moghissi Endowed Chairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Supplemental Figure 1

Blastocysts have significantly more cells after 24hr of culture, but BR-DIM or Metformin significantly decrease cell growth compared with unstimulated embryos at the end of culture. Morulae were cultured overnight to acclimate to culture to blastocyst stage, one group was fixed and counted for cells and the rest were preloaded with CC (5uM) for 2h and then continued +/-CC with stimuli BR-DIM (20uM) or Metformin (40uM), for an additional 24hr and then fixed cells were counted and graphed. Triplicate biological experiments using 174 embryos were performed, tested for normal distribution by ANOVA and significance by Dunnett post hoc t-test. (a) Shows significance compared with KSOM and b shows lack of significance for each stimulus with CC compared with the stimulus alone. (JPEG 224 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bolnick, A., Abdulhasan, M., Kilburn, B. et al. Two-cell embryos are more sensitive than blastocysts to AMPK-dependent suppression of anabolism and stemness by commonly used fertility drugs, a diet supplement, and stress. J Assist Reprod Genet 34, 1609–1617 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1028-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1028-x