Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic that entered our lives suddenly in 2020 compelled higher education systems throughout the world to transfer to online learning, including online evaluation. A severe problem of online evaluation is that it enables various technological possibilities that facilitate students' unethical behaviors. The research aimed to investigate these behaviors, as well as the reasons for their appearance, as practiced in exams held for the first time during the Covid-19 pandemic, and to elicit students' and lecturers' perceptions of students' academic dishonesty (AD) during this period. The sample included 81 students and 50 lecturers from several Israeli colleges and universities. The findings expand extant knowledge on academic dishonesty, identifying significant differences between the perceptions of students and lecturers concerning attitudes towards online exams and the reasons for dishonest behaviors. The findings among the students also indicate that younger students and Arab students tended to cheat more in online exams. Moreover, the findings indicated a lack of mutual trust between students and lecturers with regard to academic dishonesty, a deep distrust that will probably continue even after the Covid-19 crisis. This last finding should be a cause of concern for higher education policy-makers, affecting future policies for improving lecturer-student relations, especially during crises. Recommendations are proposed for addressing academic dishonesty in exams in general and during the pandemic in particular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic entered our lives very suddenly, spreading widely and quickly during 2020. It forced schools, universities and other educational institutions to close for several months. In order to enable the continuation of teaching and learning activities during this difficult period, educators over the world moved from classroom teaching and learning to distant emergency classrooms or distance learning (Reynolds & Chu, 2020). Although some education systems have returned to frontal teaching, the higher education system in most countries, including Israel, continued and continues at the time in which this article is written to conduct distance learning, and online learning has therefore become the only possibility to ensure the continuation of academic teaching and learning (Cornock, 2020), in a widespread manner and without any time and place limitations. At the end of the first semester of distance learning, students' exams and evaluations were also changed to online methods.

One of the problems of online evaluations is that the variety of technological possibilities fascilitates non-ethical behavior, such as sharing information on the Internet, consulting with friends and copying contents easily (Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., 2018; Sarwar et al., 2018). Indeed, the research literature addresses academic dishonesty of students in online learning, including copying, forbidden use of learning materials, helping others, etc. (e.g. Ahmed, 2018; Birks et al., 2020; Grira & Jaeck, 2019; Stearns, 2001). The literature also addresses lecturers' perceptions concerning students' academic dishonesty (e.g. Blau et al., 2020; Pincus & Schmelkin, 2003; Stevens, 2013), although to a lesser extent. It has however been found that lecturers in general perceive academic dishonesty more severely in comparison to students' perceptions (Blau et al., 2020; Pincus & Schmelkin, 2003). However, both students and lecturers believe that it is easier to cheat in online courses (Kennedy et al., 2000). This is a worrysome phenomenon since cheating has consequences both for the students' learning process in the course of their academic studies and for the employment market that will receive them following their graduation, with the ethics they bring to that market (Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Bashir & Bala, 2018). Exams and assignments are now all conducted online and it appears that they will be conducted thus at least in the forseeable future. It therefore becomes imperative to assess this phenomenon, particularly since learning is increasingly conducted online and especially during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Academic dishonesty is not a new phenomenon. It began long before technology entered our lives and includes various behaviors. The present research aimed to examine differences between students' and lecturers' attitudes towards online exams during the Covid-19 crisis, students' reasons (motivation) for academic dishonesty during this peiod, students' testimonies of their actual behaviors during online exams and whether a correlation exists between students' attitudes towards online exams and the reasons for their academic dishonesty in these exams during the Covid-19 period.

Literature Review

The educational system and higher education system have various goals, including, in addition to the acquiring of relevant academic knowledge, the fostering of ethical and moral values. These values are known collectively as "academic integrity" and "appropriate academic behavior".

Academic Integrity

Academic integrity is defined as a commitment to fundamental moral values such as honesty, trust, fairness, decency, respect and responsibility (Keohane, 1999). These values are important in higher education institutions for the evaluation of learning, but also because these institutions are expected to enable and encourage the acquisition of knowledge, individual learning, development of intellectual abilities, development of autonomy and maintenance of the school's reputation of academic excellence (Ahmed, 2018; Nuss, 1984), as well as to produce graduates who contribute to the state's economic, social and humanistic development (Muhammad et al., 2020) and who behave morally in society. Thus, the main purpose of teaching and learning as perceived today is to foster a learning-oriented environment, based on personal motivation, more than creating an achievement-directed environment (Bertram Gallant, 2017). And indeed, when the student learns through intrinsic motivation, academic practices are usually fair (Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Krou et al., 2020). These values, which underlie academic integrity, are considered important even in times of duress, which may stem from lack of knowledge and fear of failure (Keohane, 1999), or from crises such as the present pandemic (Moralista & Oducado, 2020).

Academic Dishonesty

In contrast, academic dishonesty is defined as unethical behavior in an academic environment (Muhammad et al., 2020). This is inappropriate behavior whereby students act to gain an unfair academic advantage for themselves or for their friends in the academic community (Grira & Jaeck, 2019). Academic dishonesty prevents the development of positive values such as honesty, fairness and significant learning progress, and is connected to other negative behaviors, which have implications even beyond academia (Krou et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2018), such as in the work market in which inappropriately-skilled graduates may be employed (Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Bashir & Bala, 2018).

Research shows that such behavior is a known and prevalent phenomenon that has increased over recent years (e.g. Birks et al., 2020; Grira & Jaeck, 2019; Harper et al., 2020), and also that this is a multi-faceted cross-cultural global phenomenon (Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Bashir & Bala, 2018). For example, research in India found that slightly over 20% of 1,369 research participants admitted to academic dishonesty (Stearns, 2001). Similarly, one of the broadest and longest-term studies conducted in Australia examined 150,000 students over eight years and found that 65% of the students reported academic dishonesty in at least one of the study's parameters (Duff et al., 2006). Similarly, research conducted in Romania found that 95% of the students reported inappropriate academic behavior (Ives et al., 2017).

Research literature in this field also addresses various background factors connected to academic dishonesty: men cheat more than women (Kiekkas et al., 2020), young students cheat more than older students (Brunell et al., 2011; Macale et al., 2017; McCabe & Trevino, 1997) and Arab students cheat more than Jewish students (Sidi et al., 2019).

The research literature describes a large number of behaviors connected with inappropriate academic behavior in the traditional, non on-line learning environment, including: helping a friend in the course of an exam, cooperating with peers in the course of an exam, use of prohibited materials in exams, use of friends' materials, allowing work to be copied, attaining solutions from friends who have already taken the exam, taking an exam for someone else, plagiarism (including materials copied without giving credit to the author, repetitive use of an assignment already submitted, work written by a third party and presented as the student's work or purchasing works – contract cheating), cooperation between friends to write works when there is no permission to do so and adding resources to the bibliography without using them (Denisova-Schmidt, 2017; Harper et al., 2020; Von Dran et al., 2001; Yu et al., 2018).

A recent study reported that most of the behaviors considered as lacking academic integrity are connected to assistance during an exam, the most prevalent being giving and accepting the assistance of friends in multi-choice exams and in exams where short answers are required (Harper et al., 2020).

Moreover, there is an increase in students' motivation to pay an outside factor to do their assignments (contract cheating) (Birks et al., 2020). It was found that the main reasons for the use of contract cheating were dissatisfaction with the teaching and learning environment, lack of time and the perception that there were many opportunities to cheat (Bretag et al., 2019; Foltýnek & Králíková, 2018). In Australia, it was found that students use contract cheating provided by their immediate social circles rather than external contractors (Harper et al., 2020).

A recently published meta-analysis by Krou et al. (2020) of various research studies investigating inter alia, behaviors in various fields (sciences, technology, engineering, maths and business streams) categorized behaviors associated academic dishonesty into two categories: plagiarism (materials copied without giving credit to the author, work written by a third party and presented as the student's work etc.) and cheating (receiving answers from a student who had already completed the exam, collaborating with friends on an assignment without permission, copying during an exam, and use of auxiliary materials without permission during an exam). Moreover, it was found that students who witnessed inappropriate academic behavior of their friends tended to perform similar behavior, in contrast to students who did not witness such behaviors (Ahmed, 2018; Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Kiekkas et al., 2020). In other words, a norm of appropriate or inappropriate academic behavior influenced the students' behavior.

Reasons for Academic Dishonesty

The reasons for students' academic dishonesty are many and varied and stem from personal-intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Personal-intrinsic factors include strong motivation to succeed, competitiveness, fear of failure, insufficient knowledge in the discipline, a diminished sense of self-efficacy, a large overload of studies, insufficient self-discipline, laziness, tiredness, an impulsive tendency, previous low academic achievements and low moral development. Extrinsic factors include the ignoring of unethical behavior by staff members and an absence of disciplinary implications for cheating, parents' pressure to succeed, dissatisfaction with the teaching, a sense that there are multiple cheating opportunities, time pressure to hand in assignments, excesively high academic demands, content's irrelevance to the students' future profession, a desire to attain better social status and a desire to enter the work market (Amigud & Lancaster, 2019; Birks et al., 2020; Bretag et al., 2019; Kiekkas et al., 2020; Krou et al., 2020; Murdock & Anderman, 2006).

The reasons for these behaviors can be categorized according to three motivational mechanisms: (1) What is my purpose? This includes consideration of the student's intrinsic and extrinsic motivation; (2) Can I do this? This includes the students' extrinsic motivation, their self-efficacy and their learning environment, including learning disabilities, an unclear exam, and the desire to be like the other learners (Bertram Gallant, 2017; Etgar et al., 2019; Murdock & Anderman, 2006); and (3) What are the costs? This includes consideration of the direct costs of being caught but also the psychological burden of such dishonest academic behavior (Bertram Gallant, 2017; Etgar et al., 2019; Murdock & Anderman, 2006).

Academic dishonesty was found to correlate positively with extrinsic motivation (Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Grira & Jaeck, 2019; Krou et al., 2020; Murdock & Anderman, 2006) and negatively with intrinsic motivation (Barbaranelli et al., 2018; Foltýnek & Králíková, 2018; Grira & Jaeck, 2019; Murdock & Anderman, 2006). However, it is not only motivation that influences these behaviors.

Literature in this field indicates that students' perceptions academic dishonesty can explain some of these behaviors (Kiekkas et al., 2020). Statements such as "its not such a big deal", "its not really cheating", "its my teacher's fault", or "everyone cheats" (Stephens et al., 2007, p. 325) are examples of students' perceptions of lack of integrity as something that is not a serious matter. Moreover, students do not always perceive certain behaviors, such as use of materials without noting the source (Moss et al., 2018) or use of hidden notes in an exam, as behavior characteristics of academic dishonesty (Kiekkas et al., 2020).

Academic Staff Attitudes Towards Students' Academic Dishonesty

In contrast to students' attitudes, teaching staff regard academic dishonesty far more seriously (Blau et al., 2020; Stevens, 2013). Pincus and Schmelkin (2003) even found that lecturers regard behaviors such as copying in an exam, use of forbidden materials during an exam, taking an exam for someone else and paying someone to write a paper as severely inappropriate behaviors. Failure to contribute to group work, lying and presenting the same paper in more than one course are all behaviors regarded by lecturers as less severe. However, in general, lecturers take all behaviors that exhibit academic dishonesty more seriously than students, and regard more behaviors as manifestations of academic dishonesty than do the students.

Online Learning and Academic Dishonesty

Academic dishonesty has preoccupied the academia for many years, but this phenomenon has increased in recent years. One of the reasons for this increase is the growth of online teaching, and the technologies that facilitate these behaviors (Etgar et al., 2019; Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., 2018; Sarwar et al., 2018).

In the last decade, innovative learning approaches have been introduced into the higher education system. The development of technology and its prevalent use have led higher education institutions to introduce online courses, either fully online or hybrid courses, into their academic learning programs (Lee-Post & Hapke, 2017; Marshall & Varnon, 2017). This approach enables an increase in full and easy access to learning contents, use of social media, Wikipedia, sharing sites, etc. (Ahmed, 2018; Lee-Post & Hapke, 2017; Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., 2018). In fact, digital technology such as Smartphones, palm computers, mobile computers and PCs and the Internet enable more flexibility, creativity and sometimes even accuracy and effectiveness. They therefore assist teaching and learning processes, since they enable photography and storage of various learning materials (Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., 2018; Stephens et al., 2007), sharing of knowledge and integration of various methods to make learning more active and involved.

However, integration of online courses without integrating rules for ethical behavior suitable for the online environment and special techniques to prevent academic dishonesty provides fertile ground for an increase in the frequency of inappropriate academic behavior (Marshall & Varnon, 2017). Moreover, the very advantages of integrating technology in learning (comfort, flexibility and access to information) became the largest incentives for dishonest behavior (Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017; Muhammad et al., 2020; Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., 2018). An example of this is plagiarism, which—because of the easy access to information—becomes easy to use with copy-paste, far more easily than copying (Sidi et al., 2019).

Research indicates that students began to use unauthorized technological tools such as Smartwatches and Smartphones for these behaviors (Birks et al., 2020; Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017). It has also been found that lecturers and students both believe that it is easier to cheat in online courses (Kennedy et al., 2000).

In an unsupervised learning environment, there are additional explanations for unethical behavior following the integration of technology (Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., 2018), such as a surfeit of Internet-based applications accessible to students, easy access to unauthorized support from outside of the campus (outsourcing), insufficient face-to-face interactions with teaching staff in online courses leading to a decrease in moral commitment, insufficient feedback on academic learning activities, inappropriate guidelines for students on the way to study online, lack of appropriate training for online learning and lack of appropriate monitoring mechanisms (Von Dran et al., 2001). Nevertheless, it should be noted that the technology per se is not the cause of dishonest behavior, it just makes it easier and enables it to take place (Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017; Etgar et al., 2019; Sarwar et al., 2018). There are also few effective specially-devised techniques for preventing academic dishonesty, a factor that may also explain the increased prevalence of inappropriate academic behavior (Marshall & Varnon, 2017).

Research has also shown that many behaviors that are considered as academic dishonesty and are connected with digital tools stem from students' insufficient knowledge about and understanding of ethical behavior (Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017). For example, "copy-paste" is not always perceived as an unethical practice. Another important point is the academic perception of academic dishonesty in the digital space as less harmful than academic dishonesty in the analogous academic spaces, since in the digital space it is perceived as "white collar crime" (Etgar et al., 2019, p. 141), and as such it is regarded as less damaging. Thus, punishments for this behavior are less severe in comparison to punishments in analogous academic institutions (Etgar et al., 2019).

Given all the above, and in order to investigate students' and lecturers' perceptions concerning dishonest academic practices in the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, the following research questions were set:

-

1.

What are the differences between the attitudes of students and lecturers towards students' academic dishonesty in exams during the Covid-19 pandemic?

-

2.

What are the reasons (motivations) for students' dishonest behaviors in online exams during the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, and are there differences between lecturers and students in their perceptions of the reasons for these behaviors?

-

3.

What are the differences between lecturers and students testifying to their classmates' behavior in their estimation of the likelihood of students' unethical behavior during online exams in the course of the Covid-19 crisis?

-

4.

What is the correlation between students' attitudes towards online exams, their reasons for dishonest behaviors and their self-testified unethical behaviors in practice in online exams during the Covid-19 crisis?

Methodology

The research employed quantitative methodology in order to reveal the students' motivations for behavior that symbolize academic dishonesty, and the correlation between these motivations and their actual self-testified behaviors in practice, as well as to identify differences between students and lecturers in their perception of unethical behavior in exams during the Covid-19 pandemic, using a questionnaire based on a tool developed and validated by Peled et al. (2018). All the statements were adapted for the present research, especially for the online evaluation of the questionnaire structure. The questionnaire consisted of five sections. The first section pertained to the reasons for the students' academic dishonesty (graded on a Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very large extent). The second section examined the probability of students' dishonest behavior (on a Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very large extent). The third section examined the frequency of these dishonest behaviors among the students (on a Likert scale where 1 = never and 5 = many times). The fourth section examined attitudes towards online exams (Likert scale where 1 = do not agree at all, and 5 = fully agree); and the fifth section included background questions about the respondent, such as gender, age, nationality, academic institution, socio-economic status etc. Most of the questionnaire examined unethical behaviors of the students' peers (using the principle of projection), except from the third part, which addressed the respondents' own unethical behaviors, as well as the background questions. The reason for the use of the projection principle was to create a psychological defense mechanism, in which the respondents address others rather than their own characteristics, which they usually deny (Krosnick, 2018).

The respondents were asked to answer the questionnaire through reference to the exam period immediately following the end of the second semester (August 2020), which had been the first semester in which they had studied completely online. The questionnaires were distributed to the students and lecturers, and the phrasing was adapted for the particular audience (for example, a statement in the students' questionnaire addressing reasons for academic dishonesty behaviors of students was phrased: "During the Covid-19 pandemic period there is no time to study", while a similar statement in the lecturers' questionnaire was phrased: "During the Covid-19 pandemic period the students do not have time to study"). Tables 1 and 2 display the structure of the students' and lecturers' questionnaire respectively.

The questionnaires were structured in their entirety with the assistance of Google Form and distributed through WhatsApp groups and the students' and lecturers' emails, using a comfort sample and snowball sampling. The time required to complete the questionnaires was, on average, ten minutes. The questionnaires were distributed in 2020 and data collection continued for a month. In the questionnaire there was no consideration of the theoretical frame dealing with motivations for violating academic integrity, so that exploratory factor analysis was performed on the statements dealing with reasons for lack of academic integrity (details appear in the Findings section).

Participants

The sample included 81 students, 60% of them studying in academic colleges throughout Israel and the remaining 40% studying in Israeli universities.

All the student respondents were studying for a Bachelor's degree. 24.7% were male and the remainder were female. 49% were Jewish and the remaining 51% were Arab. The Arab students' mean age was 23.13 years (SD = 3.37) and the Jewish students mean age was 29.00 years (SD = 8.57). It is noted that in one of the colleges the percentage of Arab students was high, a fact that had implications for their high percentage in the sample.

The sample also included 50 lecturers, 90% of whom taught at the time in academic colleges throughout Israel and the remaining 10% in universities. 46% of the lecturers were male and the remaining 54% were female. 84% of the lecturers were Jewish and the remaining 16% were Arab. The lecturers' mean age was 50.21 years (SD = 8.892).

Thus, the total sample size was 131 participants. This sample size is adequate according to the GPower tool (Faul et al., 2009). We anticipated medium effect sizes and set the power at 0.80 and alpha at 0.05, which resulted in a desired total sample size of 102 participants.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed with the assistance of the statistical software SPSS (Version 23), and included descriptive statistics, factor analysis, t-tests for independent samples, paired sample t-test, Pearson correlations, two-way ANOVA, and hierarchical regression.

Ethics

The research was authorized by the Research Ethics Committee in the academic institution in which both researchers teach.

Findings

According to the findings, 66% of the lecturers reported that they had altered their method of evaluation in the present semester because of the transition to online learning. For 50% of the lecturers this was because of apprehension of copying and apprehension that the academic level would be harmed, 6% stated it was in order to reduce students' anxiety and uncertainty during the Covid-19 pandemic, 6% in order to encourage independent learning and 3% because of the transition of exams to online methods.

What was the perception underlying this change? In order to test this, we first examined the students' and lecturers' attitudes towards online exams during the Covid-19 period and whether there were differences in their attitudes. We then examined the reasons for the students' dishonest behaviors in exams during the pandemic. In the next stage we examined the differences in estimates of the probability that students would behave dishonestly in online exams during the Covid-19 period between students testifying to the behavior of their peers and lecturers. Finally, we examined correlations between the students' attitudes towards online learning and the reasons for dishonest behavior in practice in exams during the Covid-19 period.

Question 1 asked: 1.What are the differences between the attitudes of students and lecturers towards students' academic dishonesty in exams during the Covid-19 pandemic?

In order to answer this research question, descriptive statistics and independent-sample t-test were used. The results appear in Table 3.

The findings indicate that the students held negative attitudes towards online exams, particularly expressing distrust towards the lecturers and frustration with the online exams. A significant difference was also indicated between lecturers' and students' attitutdes in almost all the variables that described attitudes towards online exams during the pandemic, with the lecturers grading these attitudes significantly higher than the students. In other words, the lecturers believe that the students are more frustrated with online exams than the students testify themselves, they are more concerned about a decrease in the academic level than the students, and are more angry with the students who cheat than the students themselves. The only variable for which there is no significant difference between the students' and lecturers' atttitudes is the variable that addressed the distrust between the students and lecturers, which both populations graded as relatively medium–high, while both sides agreed that there is a distrust between them during the Covid-19 pandemic online exams period. It should be noted that the standard deviation is rather high for certain variables, so that there is variance in the reasons and behaviors associated with academic dishonesty for those variables.

The second research question examined the reasons for students' dishonest behaviors in online exams during the Covid-19 pandemic, and investigated whether there were differences between the students' and lecturers' perceptions of the reasons for those behaviors. In order to respond to this question, we first performed factor analysis in order to test the reasons for students' dishonest behaviors. The factor analysis results appear in Table 4.

The factor analysis clearly indicated three reasons for the students' dishonest behavior in online exams during the Covid-19 crisis: Cost vs. benefit, e.g. "its very easy to copy", "there is little risk of getting caught"; extrinsic reasons (e.g. "it’s a lecturer that I don't like/respect", "there is no time to study"); and academic difficulties ("the online evaluation makes lecturers write more difficult exams", "the learning material was difficult").

In the next stage we performed a two-way mixed ANOVA test, between-within students and lecturers to find the reasons for variance.

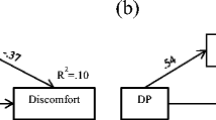

In order to examine whether there was an interaction between the populations (lecturers/students) and the reasons (learning difficulties/cost vs. benefit), variance was examined between-within in a set of 2*2. A significant interaction effect was found (F(1, 129) = 95.28, p < 0.001). In order to examine the source of the interaction, a post-hoc analysis was performed. The sample was divided into students and lecturers using t-tests for dependent samples. It was found that the lecturers reported more reasons for the students' dishonest behavior connected to cost vs. benefit (mean = 3.90, SD = 0.75), in contrast to reasons related to learning difficulties (mean = 2.93, SD = 0.85). An inverse pattern was found for the students, who graded reasons for dishonest behavior related to learning difficulties highest (mean = 3.66, SD = 0.95), in contrast to cost vs. benefit reasons (mean = 2.84, SD = 1.02). The two groups' reason mean is shown in Fig. 1.

Note: since there was a different composition of statements that referred to extrinsic reasons for students' dishonest behavior in the questionnaire that was distributed to the lecturers and the questionnaire distributed to the students, they were not entered into the two-way mixed ANOVA. These findings indicate that the lecturers believed that students cheat because it's easy for them to do so in online exams, while the students testified that they cheat because of their learning difficulties.

The third research question examined differences between lecturers and students testifying to their classmates' behavior in their estimation of the likelihood of students' unethical behavior during online exams in the course of the Covid-19 crisis. Table 5 presents these differences.

The findings indicate that the lecturers graded the likelihood of students' dishonest behavior at a higher level than the students did, and significant differences in the likelihood of students' dishonest behavior between students testifying to the behavior of their peers and lecturers. The lecturers believed that students tend to share assignments that are meant to be submitted independently, while the students believed that there is less likelihood for these behaviors among their peers. The lecturers believed that students tend to copy in exams, while the students believed that there is less likelihood of this happening among their peers. Both students and lecturers agreed that the dishonest behavior that was performed least was submitting an exam solved by someone else.

The fourth research question examined whether a correlation exists between the students' attitudes towards online exams, reasons for dishonest behavior and their actual dishonest behavior in practice (according to their own testimony) in online exams during the Covid-19 crisis.

First, the distribution of the frequencies of students' behaviors in practice were tested, with 41% of the students testifying that they had not performed any dishonest academic behaviors, and 59% reporting that they had performed some type of dishonest academic behaviors.

The next stage involved an examination of correlations between background variables, attitudes towards online exams, reasons for dishonest academic behavior and students' dishonest behavior in practice. These correlations were only tested for the students. To test the correlations, a Spearman test was conducted, since the variable that tested the students' behavior in practice did not have a normal distribution. Table 6 presents the correlations between the variables.

The findings indicate correlations between the various background variables and students' dishonest behavior: younger students copy more than older students. It was also found that Arab students copied more than Jewish students. Additionally, it emerged that when the benefit from copying exceeds the risks of being caught, the students' dishonest behaviors increased, or in other words they were more likely to copy. Also, insofar as the students experienced more learning difficulties and insofar as there are external factors that harm their studies (lecturer's quality, time management), the reason that they tend to copy is calculation of cost vs. benefit.

A strong positive correlation was also found between learning difficulties and attitudes towards online exams. In other words, when there were more learning difficulties, higher grades were given to negative attitudes towards online exams (distrust between students and lecturers increases, there is more frustration concerning the transition to online exams, etc.). No significant correlation was found between students' attitudes towards online exams and their actual dishonest academic behavior.

In the last stage, linear regression was performed in three steps: first, demographic variables were entered (gender, age, nationality) in order to control them in the Regression model, then the reasons for dishonest behavior were entered (cost vs. benefit, learning difficulties and external reasons that acted as factors for dishonest behavior), and in the third step students' attitudes towards online exams were entered. The results can be seen in Table 7.

The findings indicate that no significant correlation was found between negative attitudes towards online learning and dishonest behaviors. A significant positive correlation was found between cost vs. benefit considerations and dishonest behaviors, i.e., that when the students perceived that copying in exams would benefit them and that they would not be harmed by it, then they were more likely to copy. A significant negative correlation was also found between learning difficulties and dishonest behavior, so that copying in practice was a result of cost vs. benefit considerations more than the result of learning difficulties. No significant correlation was found between extrinsic reasons and dishonest behavior. The findings also indicate that males copy significantly more than females. No correlation was found between age and dishonest behaviors.

Note that there are some differences between Tables 6 and 7. For example, the correlation matrix indicated a correlation between nationality and cheating (but not gender), while the regression analysis indicated (at the final step) that gender predicts cheating (and not nationality). These small discrepancies are probably related to a degree of collinarity in the data and the relatively small sample size.

Discussion

The research described here addresses, for the first time, students' dishonest academic behavior in online exams during the Covid-19 pandemic. The research findings expand findings reported in existing literature on students' dishonest behavior (lack of academic integrity) and the motivations for these behaviors, since it addresses the exam period during the Covid-19 crisis. This is a time of a sudden comprehensive transition to distance learning, in the course of a sudden global health and economic crisis, an unusual period that has advanced the transfer of higher education institutions' teaching and learning to distance learning, using online assessment methods (Cornock, 2020; Elman et al., 2020). The research also compares students' attidudes towards academic dishonesty with those of lecturers during this time. This examination of unethical academic conduct is important since while the Covid-19 crisis has not yet passed, teaching and learning methods may still change in the future due to the Covid-19 crisis. It is therefore important to understand the issues involved, for implementation in similar situations that are likely to reoccur in various ways in this very volatile era.

The research findings indicate that students have negative attitudes towards online exams, and that differences exist between their opinions and those of the lecturers. However, the most worrying aspect emerging from the findings is the lack of mutual trust between students and lecturers during online exams, which should be a cause for concern in the academic world. Since the pandemic is still prevalent in most of the world, it is reasonable to assume that the next exam period will also take place online, and so there is a large possibility that this distrust will increase. This seems inevitable unless suitable steps are taken to cope with evaluation and exams in manners that are appropriate the crisis period.

According with the research questions, the research attempted to discover the reasons for the students' dishonest behavior in online exams during the Covid-19 pandemic. The research literature refers to three reasons for students' academic dishonesty: (1) What is my purpose? This includes consideration of the student's intrinsic and extrinsic motivation; (2) Can I do this? This includes the students' extrinsic motivation, their self-efficacy and their learning environment, including learning disabilities, an unclear exam, and the desire to be like the other learners; and (3) What are the costs? This includes consideration of the direct costs of being caught but also the psychological burden of such dishonest academic behavior (Bertram Gallant, 2017; Etgar et al., 2019; Murdock & Anderman, 2006). Furthermore, students with extrinsic motivation cheat more than students with intrinsic motivation (Barabaranelli et al., 2018).

The present research found that in the period of online exams due to the Covid-19 crisis, the reasons that students cheat also fell into three categories: First, students were unwilling to fail in their studies and so in cases where they endured learning difficulties they tended to behave dishonestly. We called this reason learning difficulties, appropriate for the first category noted by Murdock and Anderman (2006) (What is my purpose?). The second reason that the students raised relates to their dissatisfaction with the lecturers and perceived defective management of their studies. In other words, they did not take responsibility for their behavior and blamed external factors for their behavior. Perhaps this is actually an act of finding excuses for behavior that they know is immoral. We called this reason external factors, and it also corresponds with Murdock and Anderman's second category (2006) (Can I do this?) and also the the consideration of psychological costs vs. benefits that Murdock and Anderman (2006) labelled: What are the costs? The third reason that emerged in the present study is the benefit that students reap from dishonest academic behavior, which supersedes the risk of being caught.We called this reason costs vs. benefits, corresponding with Murdock and Anderman's (2006) category Can I do this? Thus, the present research findings support and add to previous literature in this field since they relate specifically to a period in which exams were conducted online due to the world health crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Previous research literature indicates the effect of background characteristics such as gender, age and nationality on dishonest academic behavior (Brunell et al., 2011; Kiekkas et al., 2020; Macale et al., 2017; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Sidi et al., 2019).The present findings also indicate that younger students and Arab students cheat more. Possibly, the reason for this is that younger students are less mature and less prepared for academic studies, as appeared in Birks et al. (2020). Moreover, the age of the Arab students was generally lower than that of the Jewish students. In addition, the Arab society is a minority in Israel, with lower socio-demographic characteristics than those of the Jewish majority society. In many cases, education is the only hope for social mobilization of individuals in this society, to climb out of the low economic strata to which they were born. It is therefore possible that in some cases, the end is seen as justifying the means (Mok & Jiang, 2018; Rabin, 2011). At the same time, it should be stressed that when the age variable is controlled for, there is no significant difference between jews and Arabs in this respect.

However, academic dishonesty is a prevalent phenomenon, one that has increased in recent years. One of the reasons for this is the rise in online teaching and use of technology, which make such behavior easier (Birks et al., 2020; Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017; Grira & Jaeck, 2019; Harper et al., 2020; Sarwar et al., 2018).

Since the present study was comducted at a time in which all teaching and evaluation was performed online, it is reasonable to assume that dishonest academic behavior was extremely widespread during this period. However, the students themselves testified that various dishonest academic behaviors are not prevalent. At the same time, more than half of the students admitted that in practice they had acted with academic dishonesty. Two main reasons can provide for this discrepancy, the first being that the students chose to reply inaccurately when asked about their unethical behaviors, as appeared in previous studies (Gal et al., 2015; Naghdipour & Emeagwali, 2013). The second possible reason is the change in the method of evalution, which was new for the students. Possibly, this change led the students to feel that there is some unfairness in the evaluation method, since in the past they were evaluated differently and now, because of the health crisis, they were subject to a new method. This feeling may lead to dishonest behavior.

Finally, the research findings do not indicate a significant correlation between the students' attitudes towards online examinations and their dishonest academic behavior in practice. Previous literature also indicates that there is often no connection between attitudes and behaviors (Ajzen & Fishbeinm, 2005; LaPiere, 1934). It is also possible that the reason for students' motivation to cheat during online exams at the time of the pandemic is unrelated to their negative attitudes towards online exams, and that these attitudes were not the trigger for their dishonest behavior.

Given all the abovesaid, and in order to ascertain that ethical behavior, integrity and meaningful learning are maintained even in crisis situations and when using distance learning, the academic institutions need, among other things, to support the development of supportive learning and teaching environments that foster the connection between lecturers and students (Bretag et al., 2019). The present research findings and the differences found between the attitudes and perceptions of students and lecturers testify to the importance of care for this student–lecturer relationship, particularly in the difficult time of the pandemic when it's managed solely at a distance. There should be assimilation of principles of academic ethics in shared discourse between lecturers and students. Moreover, the mutual distrust between students and lecturers that was indicated in the present research findings must be corrected before the return to studies in higher education institutions.

Summary and Conclusions

Several findings revealed by this research should constitute a red light for policy-makers and lecturers in academia. First, both students and lecturers feel distrust between them during this period. This is a worrying phenomenon, and should be addressed as soon as possible, whether the next exams return to the former format (which does not seem reasonably likely given the present global morbidity rates) or of course if the next exams are also conducted online. For in these circumstances, it seems likely that the distrust will grow, since the lecturers believe that the students cheat in online exams (as was revealed in this research), and so they will do anything they can to prevent that. For their part, the students will likely use technology to cope with the lecturers' preventive measures. The following is a list of recommendations for improving student and lecturer behavior and student learning in general and particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, as a result of the research findings.

Recommendations

-

1.

Dialogue on ethics and its importance in academia for both students and lecturers should be conducted in the classrooms. It should also be possible to deliver a course on ethics in academia, and lecturers and students could decide together on an ethical code and ensure its implementation.

-

2.

Dialogue should also be carried out on the meaning of learning and its relevance in preparation for the labor market. It is important to discuss academic integrity as as an important and necessary value and ability for the employment market.

-

3.

A positive relationship and interaction between lecturers and students should be cultivated in academia. It is also important that the lecturers themselves should act as models for ethical behavior.

-

4.

Alternative assessment methods should be found, more appropriate for a dynamically changing world, in order to test understanding, thinking, processes and the ability to transfer theory to field practice.

-

5.

Rebuilding trust between lecturers and students through meetings, conversations, and expressing each side's point of view.

The Research's Limitations

The research relied on a relatively small sample of students and lecturers. Although the sample complies with the criteria determined by G-Power examination, it is recommended to use a larger sample in future research. Also, the standard deviation is quite high for various variables, so that there is variation of perceptions within the groups of students and lecturers. It would therefore be advisable to conduct the study in larger populations, both of students and of lecturers. Furthermore, interviews with students and lecturers would provide a fuller and more comprehensive picture of the perspectives of the students and lecturers regarding unethical behavior in academia.

An additional limitation is related to the research population itself. The percentage of Arab students that participated in the research is not representative of their percentage in the Israeli population, because in one of the colleges the percentage of Arab students was especially high. It is recommended that further research should ensure that the number of Arab students included are representative of their percentage in the general population.

Additionally, the research was conducted at a specific point of time during the Covid-19 pandemic, at the end of the first wave, with partial return to routine and the beginning of a second wave. This was also the first time that online exams were held exclusively in higher education institutions. The exam period was overshadowed by much confusion for both students and lecturers. Higher education institutions prepared for the exams and adapted them to the online environment "on the go" and in a state of uncertainty. It is therefore recommended that a similar study should be performed in a different period of time (if the Covid-19 crisis continues), after the higher education institutions prepare for the next set of exams in an online environment. Alternatively, if the Covid-19 pandemic abates and academic institutions are able to return to their previous format of exams, it should be possible to perform a similar study to test whether changes take place in the perceptions of the lecturers and students concerning aspects of ethics and the perceptions of each group towards the other group.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kinneret Academic College, Emek Hayarden.

References

Ahmed, K. (2018). Student perceptions of academic dishonesty in a private middle eastern university. Higher Learning Research Communications, 8(1), 1.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (p. 173–221). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Amigud, A., & Lancaster, T. (2019). 246 reasons to cheat: An analysis of students’ reasons for seeking to outsource academic work. Computers & Education, 134, 98–107.

Barbaranelli, C., Farnese, M. L., Tramontano, C., Fida, R., Ghezzi, V., Paciello, M., & Long, P. (2018). Machiavellian ways to academic cheating: A mediational and interactional model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 695.

Bashir, H., & Bala, R. (2018). Development and validation of academic dishonesty scale (ADS): Presenting a multidimensional scale. International Journal of Instruction, 11(2), 57–74.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2017). Academic integrity as a teaching & learning issue: From theory to practice. Theory into Practice, 56(2), 88–94.

Birks, M., Mills, J., Allen, S., & Tee, S. (2020). Managing the mutations: Academic misconduct Australia, New Zealand and the UK. International Journal for Educational Integrity.

Blau, I., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2017). The ethical dissonance in digital and non-digital learning environments: Does technology promote cheating among middle school students? Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 629–637.

Blau, I., Goldberg, S., Friedman, A., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2020). Violation of digital and analog academic integrity through the eyes of faculty members and students: Do institutional role and technology change ethical perspectives? Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 1–31.

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenerg, P., & van Haeringen, K. (2019). Contract cheating: A survey of Australian university students. Studies in Higher Education, 44(11), 1837–1856.

Brunell, A. B., Staats, S., Barden, J., & Hupp, J. M. (2011). Narcissism and academic dishonesty: The exhibitionism dimension and the lack of guilt. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 323–328.

Cornock, M. (2020). Scaling up online learning during the Covid-19virus (Covid-19) pandemic. Retrieved from: https://mattcornock.co.uk/technology-enhanced-learning/scaling-up-online-learning-during-the-Covid-19virus-covid-19-pandemic/

Denisova-Schmidt, E. (2017). The challenges of academic integrity in higher education: Current trends and prospects. Perspectives No. 5. Retrieved from: https://www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/research_sites/cihe/pubs/CIHE%20Perspective/Perspectives%20No%205%20June%2013%2C%202017%20No%20cropsFINAL.pdf

Duff, A. H., Rogers, D. P., & Harris, M. B. (2006). International engineering students avoiding plagiarism through understanding the Western academic context of scholarship. European Journal of Engineering Education, 31(6), 673–681.

Elman, A., Breckman, R., Clark, S., Gottesman, E., Rachmuth, L., Reiff, M., & Lok, D. (2020). Effects of the Covid-19 outbreak on elder mistreatment and response in New York City: Initial lessons. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 0733464820924853.

Etgar, S., Blau, I., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2019). White-collar crime in academia: Trends in digital academic dishonesty over time and their effect on penalty severity. Computers & Education, 141, 103621.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

Foltýnek, T., & Králíková, V. (2018). Analysis of the contract cheating market in Czechia. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(1), 1–15.

Gal, Y., Pery, L., Gal, T., & Gal, A. (2015). Knowledge bias: The student’s perception regarding copying during examinations, A case study of Israeli colleges. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 6(3), 174–188. https://doi.org/10.9734/bjesbs/2015/14776

Grira, J., & Jaeck, L. (2019). Rationality and students’ misconduct at university: Empirical evidence and policy implications. International Education Studies, 12(3), 10–23.

Harper, R., Bretag, T., & Rundle, K. (2020). Detecting contract cheating: examining the role of assessment type. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–16.

Ives, B., Alama, M., Mosora, L. C., Mosora, M., Grosu-Radulescu, L., Clinciu, A. I., & Dutu, A. (2017). Patterns and predictors of academic dishonesty in Romanian university students. Higher Education, 74(5), 815–831.

Kennedy, K., Nowak, S., Raghuraman, R., Thomas, J., & Davis, S. F. (2000). Academic dishonesty and distance learning: Student and faculty views. College Student Journal, 34(2).

Keohane, N. (1999). The fundamental values of academic integrity. The Center for Academic Integrity, Duke University, 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.academicintegrity.org/icai/assets/FVproject.pdf

Kiekkas, P., Michalopoulos, E., Stefanopoulos, N., Samartzi, K., Krania, P., Giannikopoulou, M., & Igoumenidis, M. (2020). Reasons for academic dishonesty during examinations among nursing students: Cross-sectional survey. Nurse Education Today, 86, 104314.

Krosnick, J. A. (2018). Questionnaire design. In The Palgrave handbook of survey research (pp. 439–455). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Krou, M. R., Fong, C. J., & Hoff, M. A. (2020). Achievement motivation and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic investigation. Educational Psychology Review, 1–32.

LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230–237.

Lee-Post, A., & Hapke, H. (2017). Online learning integrity approaches: Current practices and future solutions. Online Learning, 21(1), 135–145.

Macale, L., Ghezzi, V., Rocco, G., Fida, R., Vellone, E., & Alvaro, R. (2017). Academic dishonesty among Italian nursing students: A longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today, 50, 57–61.

Marshall, L. L., & Varnon, A. W. (2017). Attack on Academic Dishonesty: What" Lies" Ahead? Journal of Academic Administration in Higher Education, 13(2), 31–40.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38(3), 379–396.

Mok, K. H., & Jiang, J. (2018). Massification of higher education and challenges for graduate employment and social mobility: East Asian experiences and sociological reflections. International Journal of Educational Development, 63, 44–51.

Moralista, R., & Oducado, R. M. (2020). Faculty perception toward online education in higher education during the Covid-19virus disease 19 (Covid-19) Pandemic. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(10), 4736–4742.

Moss, S. A., White, B., & Lee, J. (2018). A systematic review into the psychological causes and correlates of plagiarism. Ethics & Behavior, 28(4), 261–283.

Muhammad, A., Shaikh, A., Naveed, Q. N., & Qureshi, M. R. N. (2020). Factors affecting academic integrity in e-learning of Saudi Arabian universities. An investigation using Delphi and AHP. IEEE Access, 8, 16259–16268.

Murdock, T. B., & Anderman, E. M. (2006). Motivational perspectives on student cheating: Toward an integrated model of academic dishonesty. Educational Psychologist, 41(3), 129–145.

Naghdipour, B., & Emeagwali, O. L. (2013). Students’ justifications for academic dishonesty: Call for action. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 83, 261–265.

Nuss, E. M. (1984). Academic integrity: Comparing faculty and student attitudes. Improving College and University Teaching, 32(3), 140–144.

Peled, Y., Eshet, Y., Barczyk, C., & Grinautski, K. (2018). Predictors of academic dishonesty among undergraduate students. Computers & Education, 131, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.012.

Peytcheva-Forsyth, R., Aleksieva, L., & Yovkova, B. (2018). The impact of technology on cheating and plagiarism in the assessment – The teachers’ and students’ perspectives. In AIP conference proceedings (Vol. 2048, No. 1, p. 020037). AIP Publishing LLC.

Pincus, H. S., & Schmelkin, L. P. (2003). Faculty perceptions of academic dishonesty: A multidimensional scaling analysis. The Journal of Higher Education, 74(2), 196–209.

Rabin Y. (2011). The right to education as a condition for the establishment of social justice. Retrieved from the Israel Democracy Institute website (https://www.idi.org.il/parliaments/8054/8056). (In Hebrew)

Reynolds, R., & Chu, S.K.W. (2020), Guest editorial. Information and Learning Sciences, Vol. 121 No. 5/6, pp. 233–239. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-05-2020-144

Sarwar, S., Idris, Z. M., & Ali, S. M. (2018). Paid academic writing services: A perceptional study of business students. International Journal of Experiential Learning & Case Studies, 3(1), 73–83.

Sidi, Y., Blau, I., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2019). How is the ethical dissonance index afected by technology, academic dishonesty type and individual diferences? British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(6), 3300–3314.

Stearns, S. A. (2001). The student-instructor relationship’s effect on academic integrity. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 275–285.

Stephens, J. M., Young, M. F., & Calabrese, T. (2007). Does moral judgment go offline when students are online? A comparative analysis of undergraduates’ beliefs and behaviors related to conventional and digital cheating. Ethics & Behavior, 17(3), 233–254.

Stevens, T. N. (2013). Promoting a culture of integrity: A study of faculty and student perceptions of academic dishonesty at a large public Midwestern university. Ph.D. diss. University of Missouri-St. Louis. Retrieved from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217322415.pdf

Von Dran, G., Callahan, E., & Taylor, H. (2001). Can students’ academic integrity be improved? Attitudes and behaviors before and after implementation of an academic integrity policy, Teaching Business Ethics, 5, 35–58.

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Johnson, B. R., Sriram, R., & Moore, B. (2018). Why college students cheat: A conceptual model of five factors. The Review of Higher Education, 41(4), 549–576.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amzalag, M., Shapira, N. & Dolev, N. Two Sides of the Coin: Lack of Academic Integrity in Exams During the Corona Pandemic, Students' and Lecturers' Perceptions. J Acad Ethics 20, 243–263 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09413-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09413-5