Abstract

This study assessed the psychometric properties of standard Western-derived instruments, the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms, and their associations with sociodemographic and wellbeing variables in a large sample of Kenyan adolescents. Self-report measures of depression (PHQ-8) and anxiety (GAD-7) symptoms, social support, gratitude, happiness, optimism, and perceived control were administered to 2,192 Kenyan youths (57.57% female) aged 12–19. Both the PHQ-8 (α = 0.78) and GAD-7 (α = 0.82) showed adequate internal consistency. EFA with a sub-sample (N = 1096) yielded a 1-factor structure for both PHQ-8 and GAD-7, a subsequent CFA conducted on the basis of a 1-factor model on another sub-sample (N = 1096) yielded good and moderate goodness of fit, respectively, for the PHQ-8 (χ2 = 76.73; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95) and the GAD-7 (χ2 = 88.19; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.95). Some 28.06% and 30.38% of participants met the clinical cut-off for depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively. Social support, gratitude, happiness, and perceived control were negatively associated with both depression and anxiety symptoms. Older adolescents reported higher symptoms while adolescents with more siblings reported lower symptoms. The western-derived PHQ and GAD met conventional psychometric standards with adolescents in Kenya; depression and anxiety symptoms showed relatively high prevalence and significant associations with important psychosocial and sociodemographic factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adolescents in low-resource regions across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are at a greater risk of depression and anxiety because of risk factors like poverty, socio-economic stress, and exposure to violence (Kilburn et al., 2016; Patel et al., 2007; Vigo et al., 2016). For vulnerable SSA adolescents, treatment is often inaccessible because of a paucity of mental health providers (World Health Organization, 2019), government under-investment in mental healthcare (Caddick et al., 2016), and a societal stigma around mental health issues that limit access to treatment (Ndetei et al., 2016).

Even when sub-clinical, adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms, are associated with many negative life outcomes. This includes impaired social and academic functioning (King & Bernstein, 2001), inferior quality of life, poor financial prospects, and an increased risk of suicide (Balázs et al., 2013; Bertha & Balázs, 2013). Because SSA is a youthful region (median age = 19; (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2016), there is a clear and urgent need for research that is dedicated to youth mental health in this region (Collins et al., 2011).

There are three areas that can benefit from a focus on youth mental research in SSA: (1) investigating the psychometric properties of the standard instruments that are used to screen for mental health problems, (2) assessing the prevalence rates of mental health problems among SSA adolescents, and (3) exploring the associations between mental health problems and sociodemographic and psychosocial variables. Research on these three areas may yield information of important clinical and public policy utility. For example, government allocation of resources can be informed by an understanding of the prevalence rates of mental health problems. Another example is that risk and protective factors can be identified if we understand the associations between mental health problems with sociodemographic and psychological wellbeing factors (Campbell & Osborn, 2021).

A need for the psychometric evaluation of standard instruments used in youth mental health research in SSA

Because of the limited mental health experts in SSA, brief and sometimes public domain instruments have become an important tool for clinical research and practice in this region. These tools are used to screen for and clinically monitor youths struggling with mental health problems. Indeed, rather than rely on structured interviews that require expert delivery, clinical research (from epidemiological studies to clinical trials) and practice has mostly relied on these standardized tools. (e.g., Abbo et al., 2013; Magai et al., 2018; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2021).

Unfortunately, many of these instruments were developed and validated for use with Western youths (Haroz et al., 2017). Cross-cultural research has shown that these tools often fail to capture salient features of mental health distress when used across diverse cultures (Bass et al., 2007; Kleinman, 2004; Lewis-Fernández & Krishan Aggarwal, 2013). Because of this, it is possible that clinical research and practice that is reliant on these tools may emphasize or underestimate some features of mental health over others (Osborn, Kleinman, et al., 2021). Indeed, some have suggested that the variance in prevalence rates from the reports of youth mental health problems in SSA, which we discuss below, is perhaps a result of the variability of the instruments used in these reports as well as a general lack of robust research on their psychometric properties with SSA populations Khasakhala et al., 2012; Magai et al., 2018; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020).

It seems therefore that there is a clear need for research that rigorously assesses the psychometric properties of the tools used in clinical research and practice in SSA (Lewis-Fernández et al., 2014; Lewis-Fernández & Díaz, 2002; Lewis-Fernández & Krishan Aggarwal, 2013). Such research will definitely facilitate important public health work in SSA. Furthermore, if these tools are complemented by locally developed instruments then they will not only help facilitate cross-cultural mental health research but also honor the socio-cultural nuance of mental health problems Kleinman & Good, 1985; Manson et al., 1985; Osborn, Kleinman, et al., 2021).

Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among Kenyan adolescents and their associations with sociodemographic and psychosocial factors.

There are a handful of investigations into the prevalence rates of youth depression and anxiety symptoms among Kenyan adolescents. One such study, with 3755 Kenyan adolescents, found that 43.17% of Kenyan adolescents endorsed clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms while 12.90% endorsed clinically elevated anxiety symptoms (Ndetei et al., 2008). Another study—which, interestingly, used a locally developed anxiety scale—found that 49.30% of school-going Kenyan youths reported clinically elevated anxiety symptoms (Khasakhala et al., 2012). This study also found 26.40% of sampled Kenyan youths endorsed elevated depression symptoms (Khasakhala et al., 2012). Finally, a more recent study with 658 school-going students reported that 45.90% of youths reported clinically elevated depression symptoms while 37.99% reported clinically elevated anxiety symptoms (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020).

While the above studies show a rather high prevalence of adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms among Kenyan adolescents, there seems to be a high variance in the rates reported in these reports. As mentioned earlier, some have attributed this variance to the use of standard Western-derived tools that haven’t been fully psychometrically validated (Khasakhala et al., 2012; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Nonetheless, it seems that there is a need to understand the prevalence rates of these syndromes among Kenyan youths. One step towards this goal is the use of psychometrically validated tools to assess for these symptoms in Kenya and other SSA countries.

Besides prevalence rates, other studies have looked at the relationship between depression and anxiety symptoms as well as the associations between these symptoms and important sociodemographic and psychosocial variables. Such research is important because it may reveal important risk and/or protective factors.

Around the world, many studies have examined the relationship between depression and anxiety symptoms. These studies have shown depression and anxiety are not only strongly and positively correlated but also especially comorbid (Cummings et al., 2014; Essau, 2003). For youths with depression, anxiety comorbidity estimates range from 15 to 75% while for youths with anxiety, depression comorbidity range from 10 to 15% (Angold et al., 1999; Avenevoli et al., 2001; Axelson & Birmaher, 2001; Cummings et al., 2014; Yorbik et al., 2004). These findings have led to very interesting discussions on what this correlation and comorbidity means. Some, one the one hand, have suggested that although youth anxiety and depression are meaningfully linked, there are important distinctions between the two (Brady & Kendall, 1992; Cummings et al., 2014). Others, on the other hand, have proposed that this distinction is only minimal and these syndromes are perhaps a manifestation of a similar underlying syndrome or collection of symptoms that reinforce each other (McElroy et al., 2018). Sadly, this very important global discussion has not been influenced by research with SSA samples; the result is a dialogue that heavily relies on the assumption of the generalizability of Western-derived research across the otherwise diverse populations (Haroz et al., 2017; Kirmayer et al., 2017).

A few trends emerge from the research on the association between depression and anxiety and sociodemographic factors in Kenya and similar SSA countries. One such trend is that sex is strongly associated with depression and anxiety symptoms: Female adolescents report higher depressive and anxiety symptoms than their male counterparts Adewuya et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2004; McGuinness Teena et al., 2012; Mitchell & Abbott, 1987; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Another trend is that age is associated with depression and anxiety symptoms with age: Older adolescents report higher symptoms than their younger counterparts (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). This has been explained by the increased psychosocial pressure that results from the nature of many education systems in SSA where older adolescents face life-defining national examinations at the end of their secondary school education (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020; Yara & Wanjohi, 2011).

Finally, research on the association between depression and anxiety and psychological wellbeing indices has revealed that psychological wellbeing may play a preventive—and sometimes therapeutic—role in the development and maintenance of these syndromes (Bartels et al., 2013; Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001). Psychological wellbeing is broadly defined as a person’s ability to experience their lives positively; it can include positive feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction as well as a lack of negative aspects like loneliness and mental health problems (Antaramian et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2019). Because psychological wellbeing is very broad, there have been many models and indices that have been proposed to measure it (see Diener 1984 and Seligman 2018 for examples). Here, psychological wellbeing is measured through self-reported happiness, optimism, gratitude, perceived social support, and perceived academic control. All of these indices have been shown, in Western samples, to be strong and negatively associated with mental health problems (Bartels et al., 2013; Joseph & Wood, 2010; Winefield et al., 2012). A recent study encouraged further research on this relationship because it can be useful to treatment and preventive efforts for SSA youths (Campbell & Osborn, 2021).

Present Study

The present study expands on the research on adolescent mental health problems in Kenya, a SSA country. With a large community sample of Kenyan youths, the study:

-

1)

Investigated the psychometric properties of two Western – developed standardized instruments used to screen for youth depression and anxiety,

-

2)

Used these instruments – after establishing their psychometric validity – to investigate the prevalence rates of youth depression and anxiety symptoms, and.

-

3)

Explored the relationship between depression and anxiety symptoms and their associations with sociodemographic factors, like age and sex, and psychological wellbeing factors, like happiness and gratitude.

We used two brief and public domain standard instruments to assess for depression and anxiety symptoms. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to assess for depressive symptoms (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002) while the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) was used to assess for anxiety symptoms (Spitzer et al., 2006). Both are short and freely available. This is a characteristic that makes them scalable for use across SSA. One recent study showed that the PHQ and the GAD demonstrated adequate internal consistency with Kenyan adolescents (Cronbach’s alpha score of > 0.70 ; (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Another study, albeit with Kenyan adults, found that that PHQ overlapped significantly with a locally developed measure of depression (Osborn, Kleinman, et al., 2021). As a result, it was predicted that the both the PHQ and the GAD would demonstrate adequate psychometric properties in our present study.

When investigating the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety symptoms amongst Kenyan youths, we predicted that we would find a high prevalence rate of these symptoms. This is because Kenyan youths are exposed to more environmental risk factors ,such as poverty, which contribute to the development and maintenance of mental health problems (Kilburn et al., 2016). Still, the limited studies with Kenyan youths that have shown that many Kenya youths report clinically – elevated symptoms that range from 25.70% to as high as 49.30% Khasakhala et al., 2012; Magai et al., 2018; Ndetei et al., 2008; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020).

Influenced by research in Western contexts that have established that depression and anxiety are strongly and positively correlated and especially comorbid (Cummings et al., 2014; Essau, 2003), we hypothesized that depression and anxiety symptoms would be strongly and positively correlated. This hypothesis was also informed by a recent study with Kenyan adults that found a significant overlap between the features of psychopathology as defined by a standard Western-derived measure and a locally developed one (Osborn, Kleinman, et al., 2021).

In addition, the study explored the associations between depression and anxiety symptoms and sociodemographic factors. The hypothesis was that these symptoms would be significantly associated with age and sex. This is because of the Kenyan education system where older youths are at an increased psychosocial pressure and stress (which may lead to higher symptoms) due to the do-or-die nature of the end-of-secondary school examinations that determines future life prospects (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020; Yara & Wanjohi, 2011). Similarly, in Kenya and across SSA have shown that depression and anxiety symptoms female adolescents report higher symptoms than their male counterparts Adewuya et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2004; McGuinness Teena et al., 2012; Mitchell & Abbott, 1987; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020).

Finally, the study investigated the association between depression and anxiety symptoms and the following psychological wellbeing indices: self-reported happiness, optimism, gratitude, perceived social support, and perceived academic control. Because studies with Western samples have shown that these psychological wellbeing indices and mental health problems are strongly and negatively associated (Bartels et al., 2013; Joseph & Wood, 2010; Winefield et al., 2012), we predicted that we would find similar negative associations with Kenyan youths.

Methods

Study Setting.

The study took place across four secondary schools in Nairobi and Kiambu counties, Kenya. In Kenya, all students take a national-administered secondary school entrance examination at the end of eighth grade (Class 8). The best-performing students are admitted to top-ranked secondary schools known as national schools. Through a government-enforced quota system, national schools admit students from all geographical regions in Kenya. The next-tier of best-performers are admitted to extra-county schools which admit students from four to five neighboring counties. The rest of the students are admitted to county schools and then sub-county schools based on their performance (Ndetei et al., 2008). It is important to note that most secondary schools are public single-sex boarding schools (~ 70%) and that the few day-attendance schools are majority mixed-gender (Ministry of Education, 2014). Because the Kenyan government recently implemented a 100% transition policy—in which all students who complete the national examination are admitted to secondary school—it is estimated that almost 80% of Kenyan youths attend secondary schools (Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, 2015). Because there are more than 42 tribes in Kenya, we used a minority/majority tribe classification model that has been used in a recent study with Kenyan youths (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). In that classification, tribes that were aligned to the ruling Jubilee Alliance—mainly the Kikuyu tribe and affiliated Bantu-speaking tribes the Kalenjin tribes— were classified as “majority” while tribes associated with the National Super Alliance coalition— the Luo and Luhya and Akamba and Swahili-speaking tribes along the Kenyan coast—were classified as “minority” tribes.

There four participating secondary schools were selected to reflect the academic and resource diversity in Kenyan secondary schools as classified by the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education, 2014). As such, the resulting sample included two secondary schools – School A (all-boys) and School B (all-girls) – ranked as national schools (allowing us to sample students from all geographical regions in Kenya). School C (all-girls) and School D (mixed gender) were low-income county and sub-county schools respectively. Our sample, though convenient, was larger, and to the best of our knowledge, more diverse than samples from previous studies in Kenya (e.g., Khasakhala et al., 2012; Magai et al., 2018; Osborn et al., 2020). This strengthens our ability to address study hypotheses and consider results that are at least more generalizable than previous attempts. See Appendix A (Supplementary Materials) for more information on the characteristics and socio-demographics of participating schools.

Participants.

Eligible participants were adolescents (ages 12–19) attending the four participating secondary schools. The study recruited 2,192 adolescents (57.57% female; M age = 15.21, SD = 1.14). See Appendix A (Supplementary Materials) for participant demographics.

Procedures.

All procedures were approved by a local ethics review board – the Maseno University Ethics Review Committee (MUERC). A research permit was granted by the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI). All students in forms one, two and three (equivalent to 9th – 11th grades) were notified about the study at a gathering in their school halls. Here, the study team explained study procedures and offered students an opportunity to ask questions. Parental consent for underage adolescents was obtained through the school administration per MUERC guidelines. All students who wished to participate in the study provided informed consent (or assent for minors) before completing study activities. See Appendix A (Supplementary Materials) for sample characteristics.

Consenting students completed a questionnaire battery, which was administered in English. English is an official language in Kenya and the primary language of instruction at all levels of education in Kenya. All students in secondary schools are required to demonstrate proficiency in written and oral English before admission. As a result, there was no need to translate the questionnaires into any other language. Many studies with Kenyan youths have also conducted study activities in English Khasakhala et al., 2012; Ndetei et al., 2008; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2021). To control for ordering effects, there were two versions of the questionnaires with measures in different order.

Measures.

Depression and anxiety symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), a brief diagnostic measure for depression (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002). The PHQ-8 is the eight-item version of the PHQ-9, which excludes the suicidal ideation item (Kroenke et al., 2009). We excluded the suicidal ideation item because previous research with Kenyan youths has suggested that that item might be stigmatizing (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). PHQ-8 scores range from 0 to 24 with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. We used cut-off norms from primary care studies in with youth samples in the United States; the cutoffs for mild, moderate, moderately-severe, and severe depression are 5, 10, 15, and 20, respectively; scores of 10 and above on the PHQ-8 are considered clinically elevated (Kroenke et al., 2001). In a recent study, the PHQ-8 documented adequate internal consistency (α = 0.73) in a sample of 658 youths (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-8 in the present study was α = 0.78.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener-7 (GAD-7), which is a brief, cost-effective measure of generalized anxiety (Spitzer et al., 2006). Scores on the GAD-7 range from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms. Here, we used cutoff norms from primary cares studies with youths in United States: the cutoffs for the GAD-7 are 5, 10, and 15, indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively; scores of 10 and above are considered clinically elevated (Spitzer et al., 2006). GAD − 7 has documented adequate internal consistency (α = 0.78) with Kenyan youths (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). The cut-offs for the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 have been used in recent clinical trials with Kenyan youths (Osborn, Rodriguez, et al., 2020; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2021). Cronbach’s alpha for the GAD-7 in the present study was α = 0.82.

Psychosocial wellbeing indices.

Self-reported social support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988). The MSPSS has three subscales, which each address a different source of social support: family, friends, and significant other. The scale has previously demonstrated adequate internal consistency with Kenyan youths (α = 0.86) in a previous study (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Cronbach’s alpha for the MSPSS in the present study was α = 0.88.

Happiness was assessed using the EPOCH Measure of Adolescent of Well-Being (EPOCH) (Kern et al., 2016). The EPOCH measures five positive psychological characteristics, including engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, and happiness (Kern et al., 2016). The EPOCH scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = 0.70) in a recent clinical trial with Kenyan adolescents (Osborn, Rodriguez, et al., 2020). We administered the Happiness subscale for which the Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.79.

Perceived academic control was measured using the academic subscale of the Perceived Control Scale (PCS) (Weisz et al., 2001). The PCS measures the degree to which individuals believe they are in control of outcomes in their lives (e.g., academic achievement and performance outcomes). The PCS has also demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = 0.78) with Kenyan adolescents (Osborn, Wasil, et al., 2020). Cronbach’s alpha for the PCS in the present study was α = 0.80.

Finally, gratitude was measured using the brief Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6) (McCullough et al., 2002). The GQ-6 assesses subjective feelings of gratitude via six self-report questions (McCullough et al., 2002). In a recent study with Kenyan youths, the GQ-6 failed to demonstrate adequate internal consistency (α = 0.56; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly et al., 2020). Cronbach’s alpha for the GQ-6 in the present study was α = 0.79.

Socio-demographic information.

Socio-demographic information was collected through a sociodemographic questionnaire (see supplementary materials). Students provided their age, gender, tribe, financial status, financial status (upper-class vs. upper-middle-class vs. lower-middle-class vs. low-income), home (rural area vs. small town vs. big town vs. city), number of siblings, number of parents’ dead (none vs. one vs. both), mother’s education, father’s education, involvement in co-curricular activities, and involvement in sports. We collected these socio-demographic variables because prior research suggests that they may be potentially important in the development and maintenance of adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms Khasakhala et al., 2012; Ndetei et al., 2008; Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020; Othieno et al., 2014).

Data Analyses.

All analyses were conducted on R Studio (Version 1.2.5019); data and accompanying R code files can be found in the Open Science Framework repository (masked for review).

Psychometric properties of the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7.

Internal consistency and convergent validity.

To investigate the psychometric properties of the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7 with Kenyan adolescents, we, first, calculated Cronbach’s alpha to determine the internal consistency. We did this for all the measures used in the study (see Measures section). Only measures with an alpha of 0.70 and above were included in further analyses (Nunnally, 1978). All measures, except the Optimism sub-scale of the EPOCH Measure of Adolescent of Well-Being, met this requirement. As a result, we removed the Optimism sub-scale from further analyses.

We also investigated the convergent validity of these instruments by calculating whether they were negatively correlated with the psychological wellbeing indices: happiness, gratitude, social support, and perceived academic literature. Existing literature to suggests that these variables should be negatively correlated with depression and anxiety (Bartels et al., 2013; Winefield et al., 2012).

Construct validity of the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7.

Exploratory Factor Analysis. We assessed the construct validity of the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 measures by examining their factor structures. To do this, we split the total sample into 2 randomly selected subsamples, each with 1,096 participants. With the first subsample, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with maximum likelihood estimation with items of the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7, separately. Promax oblique rotation was performed because the items of each of the individual items in the scales may be correlated with each other. The number of factors to be extracted was determined using the criterion of eigenvalue greater than 1 and via examination of the scree plot.

When conducting the EFA analyses, we conducted the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test to assess if our data were suitable for factor analysis. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy assesses the extent to which the proportion of variance among variables is a result of shared variance: the lower the proportion, the better-suited data is for factor analysis. KMO scores of between 0.8 and 1 indicate that data sampling is adequate (Hill, 2011; Kaiser, 1970). We also performed Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity to verify whether factor analysis could compress the data in a meaningful way: significant values below the p < 0.05 threshold indicate that data is suitable for factor analysis (Gleser, 1966; Williams et al., 2010).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis. With the second subsample, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7. We used the lavaan package in R for model fitting using maximum likelihood estimation (Rosseel, 2012). We standardized latent factors to allow for free estimation of all factor loadings; goodness of fit was assessed using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker – Lewis Fit Index (TFI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). TFI scores of > = 0.9 indicate acceptable fit, scores of > = 0.95 indicate a very good fit; CFI score of > = 0.9 indicate acceptable fit and scores > = 0.95 indicate a good fit; RMSEA values of no greater than 0.05 indicate good fit, values between 0.05 and 0.08 indicate moderate fit, values of greater than 0.08 indicate a poor fit (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Finally, after establishing the models for single groups, we conducted multiple-group analyses to assess for both sex and age invariance using a model with equality constraints (same factor loadings across groups) and without equality constraints (different factor loadings). Maximum likelihood χ2 values were used to assess model fit; a non-significant difference in χ2 values would indicate that factor loadings are equal between the groups.

Does one factor underly the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7?

Besides investigating the construct validity for the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7, we also conducted an EFA with 1 of the subsamples from prior analyses. Here, we included all the items of the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7. Our procedures were like earlier EFA procedures. We also conducted a CFA with the second sub-sample.

Association between depression and anxiety symptoms and psychosocial wellbeing and sociodemographic factors

We used linear mixed-effect modeling to assess the relationship between depression and the psychological wellbeing indices (social support, happiness, gratitude, and perceived control). Linear mixed-effect modeling allowed us to reflect the hierarchical nature of our data in the model (Knafl et al., 2009) and have been used in similar studies (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). The variables of social support, happiness, gratitude, and perceived control were all included as covariates in the model. We included a random intercept that allowed for participant variation in symptoms by school. We used the same approach to assess the relationships between anxiety and the above-mentioned psychological wellbeing variables.

Similarly, we used a linear mixed effect model to assess the relationship between depression and various sociodemographic factors: age, gender, tribal status, financial status, home, number of siblings, number of parents’ dead, mother’s education, father’s education, involvement in co-curricular activities, involvement in sports, and perceived academic abilities. These sociodemographic factors were all included as covariates in the model. A similar approach was used to assess the association between anxiety symptoms and socio-demographic factors.

Data nesting and missingness.

Our data had two levels of nesting (participants nested within schools) thus our use of linear mixed effect model. Missing data were imputed five times using the Fully Conditional Specification (FCS) methodology implemented using the multivariate imputation by chained equations (mice) algorithm in R (Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011).

Results

PHQ-8 and GAD-7 psychometrics

Internal consistency and convergent validity

In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78 for the PHQ-8 and 0.82 for the GAD-7; both were above the 0.70 cutoff for acceptable internal consistency. For the other variables, the Cronbach’s alpha scores were 0.88 for the MSPSS (α = 0.81, Family; α = 0.82, Friends; α = 0.80, Significant Other subscale), 0.79 for EPOCH Happiness, 0.68 for EPOCH Optimism, 0.80 for the PCS academic sub-scale, and 0.79 for GQ-6.

Convergent validity was assessed using Pearson’s correlations. Table 1 shows the correlations between depressive and anxiety symptoms and a series of psychological wellbeing variables. As expected, depression and anxiety symptoms were moderately and negatively associated with social support (including social support from family, friends, and significant others), happiness, gratitude, and perceived control.

Factor structure PHQ-8 and GAD-7

Using data from subsample 1 (N = 1096), an EFA yielded a 1-factor structure for the PHQ-8 that explained 32.00% of the variance. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.85; Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 1864.67 (p < 0.001); the eigenvalue of the factor was 3.20. For the GAD-7, an EFA also yielded a 1-factor structure that explained 39.20% of the variance. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.87; Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 2341.06 (p < 0.001); the eigenvalue of the factor was 3.46. Using data from subsample 2 (N = 1096), a CFA was conducted based on the 1-factor yielded by the above EFA for both PHQ-8 and GAD-7. The 1-factor model yielded a good goodness of fit (χ2 = 76.73; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95) for the PHQ-8 and a moderate goodness of fit (χ2 = 88.19; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.95). See Table 2.

We also applied CFA separately for boys and girls to see whether the items in the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 represented a unidimensional structure within the sex subgroup. For the PHQ-8, the 1-factor model yielded a moderate goodness of fit for boys (N = 930; χ2 = 116.77; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.90) and a good goodness of fit for girls (N = 1,262; χ2 = 87.85; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.95). The 1-factor model for the GAD-7 also yielded a moderate goodness of fit for both boys (N = 930; χ2 = 90.21; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94) and girls (N = 1,262; χ2 = 121.50; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94).

Finally, we conducted a multiple-group CFA to test for invariance between boys and girls. When the models with and without equality constraints were contrasted, with the full sample, the model showed that the factor loadings of the items in the PHQ-8 were invariant across boys and girls (Δχ2 = 3.73; p = 0.811); the same was observed for the GAD-7 (Δχ2 = 4.52; p = 0.606). See Table 2.

Does an underlying factor underly the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7?

Using data from subsample 1 (N = 1096), an EFA yielded a 1-factor structure for the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 combined that explained 33.00% of the variance. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.93; Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 4880.35 (p < 0.001); the eigenvalue of the factor was 3.20. Using data from subsample 2 (N = 1096), a CFA was conducted based on the 1-factor yielded above for the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 combined. The 1-factor model yielded a moderate goodness of fit (χ2 = 436.63; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.91) for the PHQ-8 and for the GAD-7 combined.

Prevalence rates of Depression & anxiety symptoms

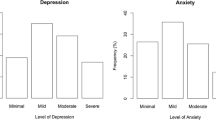

We calculated prevalence rates for depression and anxiety symptoms using cut-off norms from primary care studies with North American samples (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Spitzer et al., 2006) that have also been used with Kenyan youths (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Some 35.86% of participants endorsed mild depressive symptoms (i.e., 5–9 on the PHQ-8), 19.21% endorsed moderate depressive symptoms (i.e., 10–14 on the PHQ-8), and 8.85% endorsed moderately – severe to severe depressive symptoms (i.e., 15 or above on the PHQ-8). Thus, 28.06% endorsed clinically elevated depression symptoms. Similarly, 32.89% endorsed mild anxiety symptoms (i.e., 5–9 on the GAD-7), 19.80% endorsed moderate anxiety symptoms (i.e., 10–14 on the GAD-7), and 10.58% (i.e., 15 or above on the GAD-7) endorsed severe anxiety symptoms. Thus, 30.38% endorsed clinically elevated anxiety symptoms.

Depression, anxiety, and Psychosocial and Sociodemographic variables

Table 3 shows the results of a linear mixed effect model showing the associations between depression and psychological wellbeing indices. For psychosocial variables, we found significant effects for social support (B = -0.13, 95%CI [-0.17, -0.09], p < 0.001), gratitude (B = -0.13, 95%CI [-0.17, -0.08], p < 0.001), happiness (B = -0.21, 95%CI [-0.26, -0.17], p < 0.001), and perceived academic control (B = -0.19, 95%CI [-0.23, -0.15], p < 0.001).

Table 3 also shows the results of a linear mixed effect model showing the associations between anxiety symptom and psychological wellbeing indices. Like with depression above, we found significant effects for social support (B = -0.14, 95%CI [-0.14, 0.16], p < 0.001), gratitude (B = -0.8, 95%CI [-0.18, -0.10], p < 0.001), happiness (B = -0.24, 95%CI [-0.13, -0.03], p < 0.001), and perceived academic control (B = -0.14, 95%CI [-0.18, -0.10], p < 0.001).

Finally, Table 4 shows the results of a linear mixed effect model showing the associations between depression and anxiety symptoms and sociodemographic variables. For depression, significant effects emerged for age (B = 0.12, 95%CI [0.07, -0.16], p < 0.001), number of siblings (B = -0.06, 95%CI [-0.10, -0.02], p = 0.007), not being well-off financially (B = -0.13, 95%CI [-0.24, -0.02], p = 0.017), and some co-curricular involvement (B = 0.27, 95%CI [0.13, 0.42], p = 0.01). For anxiety, significant effects emerged for age (B = 0.10, 95%CI [0.06, -0.15], p < 0.001), number of siblings (B = -0.04, 95%CI [-0.08, -0.00], p = 0.049), being quite well-off financially (B = 0.31, 95%CI [0.09, 0.53], p = 0.006), and some co-curricular involvement (B = 0.26, 95%CI [0.12, 0.40], p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, standard Western-developed measures of depression, anxiety, and psychosocial wellbeing were administered to a large community sample of Kenyan adolescents. First, some psychometric properties of these measures were evaluated to ascertain whether they exhibited adequate internal consistency as well as construct and convergent validity in our sample. The measures were then used to assess the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety symptoms as well as their associations with important sociodemographic and psychosocial wellbeing indices. By investigating some psychometric integrity of brief and public-domain measures, the present study facilitates future clinical research and practice in a region that currently relies heavily on such measures. This study paints—with a large sample—a clearer picture of the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety symptoms. It also identifies associations between these symptoms, socio-demographic, and psychosocial wellbeing factors, and is suggestive of possible risk/protective factors for further investigation.

This study found that the PHQ-8 and the GAD-7—two brief and free instrument tools—demonstrated adequate psychometric properties with Kenya youths: these tools showed adequate internal consistency, exploratory factor analyses revealed a 1-factor model to be a good fit for the data, and confirmatory factor analyses revealed that the 1-factor model was a good fit for the PHQ-8 and a moderate fit for the GAD-7. Pearson’s correlations supported the convergent validity of these measures. These findings are important because mental health research and practice, in low–resource areas with a paucity of experts, will benefit from the use of these psychometrically validated tools. Still, this study helps address a concern in youth mental health across Sub-Saharan Africa: research and practice are often handicapped by the use of Western-derived measures absent robust psychometrical evaluation.

In addition, the study found rather high prevalence rates of depression and symptoms amongst Kenyan youths. Using PHQ-8 and GAD-7 guidelines from Western settings (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Spitzer et al., 2006), some 28.06% and 30.38% of the participants reported clinically elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms respectively. This is consistent with recent findings from Kenya (Khasakhala et al., 2012; Ndetei et al., 2008) including a recent one that found that nearly 1 in 3 Kenyan adolescents reported clinically elevated symptoms of depression and/or anxiety (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020).

How do these rates compare with those from other regions? In Ghana, a recent study that used the PHQ-8 and GAD-7—participants age 12–19; mean age 16.85—found that the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety symptoms were 20.43% and 15.55% respectively (Anum et al., 2019). In Nigeria, the prevalence rates for depression and anxiety symptoms were 21.20% (Fatiregun & Kumapayi, 2014). Elsewhere, in the USA the rates for depression and anxiety were 4.80% and 6.30% respectively (Dumont & Olson, 2012). It seems that the prevalence rates of adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms – at least when measures by the Western PHQ-8 and GAD-7 – are rather high in Kenya compared to other contexts. Future studies investigating the prevalence rates of adolescent depression and anxiety are needed. These studies should complement Western-derived measures with locally developed instruments to paint a clearer and fuller picture of these syndromes in SSA youths. Should these studies reveal similar high prevalence rates, then additional research on possible explanations for these rates is needed.

In the present study, depression and anxiety symptoms were strongly and positively correlated (r = 0.68). This finding is similar to another finding with Kenyan youths (r = 0.69; (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). Around the world, depression and anxiety have been shown to moderately to strongly correlated (r = 0.67 in Ghana, r = 0.68 in Japan, and r = 0.78 in China for example; (Anum et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Masuyama et al., 2020). Besides investigating correlations, the study design in the present study does not allow speculation on the meaning of this correlation for clinical research and practice. That said, when we investigated whether one factor underlies both depression and anxiety scales, factor analyses revealed a moderate goodness of fit for a 1-factor model of the PHQ-8 and GAD-7. (Interestingly, these scores were lower than those of the individual PHQ-8 and GAD-7). Of course, further studies are required to investigate this finding, but it seems that the distinction between depression and anxiety in this context may warrant careful consideration in the SSA context. Indeed, the emerging science of network analysis suggests that rather than looking at depression and anxiety as distinct latent entities, clinical research should be more focused on identify the central symptoms of these syndromes and the nodes that connect these symptoms (Borsboom, 2017; Fried et al., 2017).

As expected, the present study found that a reduction in symptoms was associated with an increase in happiness, gratitude, perceived social support, and perceived academic control. While causal directions cannot be established from this study design, these negative relationships echo the preventative role these psychological well-being play in the development and maintenance of mental health problems (Joseph & Wood, 2010; Winefield et al., 2012). This finding may benefit future intervention development efforts in SSA by highlighting potentially non-stigmatizing avenues for assessing, preventing, and treating depression and anxiety. Perhaps targeting and improving positive psychosocial constructs, may prevent or reduce depression and anxiety symptoms (Campbell & Osborn, 2021).

Study findings also revealed that age was significantly and positively associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms. This converges with recent evidence implicating age as a significant correlate of depression and anxiety in both Kenyan adolescents (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020) and university students (Othieno et al., 2014). Age has also emerged as significantly associated with increased adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms in the West (Saluja et al., 2004). In Kenya, various explanations for this association have been proposed. Some researchers have suggested that the increased academic pressure that older Kenyan students face when they approach the end-of-secondary-school examinations leads to increased psychosocial stress that exacerbates the symptoms of depression and anxiety (Yara & Wanjohi, 2011). Moreover, older adolescents might be more conscious of the difficulties of life and the limited future prospects in low-income countries like Kenya (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020). However, further research is necessary to unravel the association between age and mental health problems among Kenyan adolescents.

Interestingly, the number of siblings was significantly associated with reduced adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms. This finding diverges from previous evidence in other contexts. In Malaysia, a study with 2,048 school-going adolescents found that an increase in the number of siblings was associated with increased depressive and anxiety symptoms (Adlina et al., 2007). We suggest that as culture undoubtedly affects the experience of mental health problems Bass et al., 2007; Kleinman, 2004; Osborn, Kleinman, et al., 2021), it is possible that within the Kenyan socio-cultural context, an increase in the number of siblings may play a preventive/buffer role against internalizing problems. Future studies are necessary to explore this interesting relationship between mental health problems and family structure.

Other factors that emerged were involvement in co-curricular activities (associated with increased depression and anxiety symptoms) and financial status (associated with reduced depression but increased anxiety symptoms). Perhaps participating in co-curricular activities puts Kenyan youths, who are already balancing intense academic pressure, at increased risk of internalizing problems. Our study offers no suggestions for the findings on financial status because we assessed financial status through self-report measures – which have been shown to be susceptible to youths reporting relative rather than objective measures.

Finally, and surprisingly, sex did not emerge as a significant factor in our model. While this finding mirrors a recent one with Kenyan adolescents which found a significant association between sex and anxiety but not with depression (Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, et al., 2020), it differs from findings that have been reported in previous Kenyan studies (Khasakhala et al., 2012; Mitchell & Abbott, 1987; Ndetei et al., 2016) and adolescents around the world (Adewuya et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2004; McGuinness Teena et al., 2012). One possible explanation may be that most Kenyan adolescents attend single-sex boarding schools whereas in a global settings, boys and girls tend to attend mixed-gender schools (it’s possible that mixed-gender settings put girls at more risk of depression and anxiety symptoms). Future studies, which will most likely reveal an association between sex and these symptoms, are required.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional design does not allow us to investigate the extent to which sociodemographic and psychological wellbeing factors play a role in the onset, maintenance, or time course of depression and anxiety. Although the sample is large and representative of different geographies in Kenya, the study design did not include a random selection of the schools in our study. Further, participants were mostly from high-achieving schools. In addition, the measures may be susceptible to acquiescence bias. The self-report methodology used in the present study may also inflate correlations due to shared method variance. Finally, as cross-cultural studies suggest that Western-derived measures may miss salient features of depression and anxiety symptoms (Osborn, Kleinman, et al., 2021; Weisz et al., 1988, 1993), future studies should complement our findings with locally-developed instruments.

Conclusions

The present study investigated the psychometric properties of two simple standard measures of depression and anxiety and used these instruments to assess the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms and their associations with psychological wellbeing and sociodemographic factors, among Kenyan youths, a largely understudied yet vulnerable population. We found a rather high prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms and identified important psychological wellbeing and sociodemographic factors that are associated with these for these symptoms. These findings provide a framework for future research that investigates similar questions of prevalence rates, psychological wellbeing, and sociodemographic associations with culturally apt measures. Ultimately, these findings contribute to global mental health research and an may inform intervention and prevention efforts.

References

Abbo, C., Kinyanda, E., Kizza, R. B., Levin, J., Ndyanabangi, S., & Stein, D. J. (2013). Prevalence, comorbidity and predictors of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents in rural north-eastern Uganda. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 7(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-7-21

Adewuya, A. O., Coker, O. A., Atilola, O., Ola, B. A., Zachariah, M. P., Adewumi, T. … Idris, O. (2018). Gender difference in the point prevalence, symptoms, comorbidity, and correlates of depression: Findings from the Lagos State Mental Health Survey (LSMHS), Nigeria. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(6), 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0839-9

Adlina, S., Suthahar, A., Ramli, M., Edariah, A., Soe, S. A., Mohd, A. F. … Karuthan, C. (2007). Pilot study on depression among secondary school students in Selangor. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 62(3), 218

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Erkanli, A. (1999). Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(1), 57–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00424

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2010). A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 462–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01049.x

Anum, A., Adjorlolo, S., & Kugbey, N. (2019). Depressive symptomatology in adolescents in Ghana: Examination of psychometric properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Journal of Affective Disorders, 256, 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.007

Avenevoli, S., Stolar, M., Li, J., Dierker, L., & Ries Merikangas, K. (2001). Comorbidity of depression in children and adolescents: Models and evidence from a prospective high-risk family study. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1071–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01142-8

Axelson, D. A., & Birmaher, B. (2001). Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depression and Anxiety, 14(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.1048

Balázs, J., Miklósi, M., Keresztény, Á., Hoven, C. W., Carli, V., Wasserman, C. … Wasserman, D. (2013). Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety: Psychopathology, functional impairment and increased suicide risk: Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(6), 670–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12016

Bartels, M., Cacioppo, J. T., van Beijsterveldt, T. C. E. M., & Boomsma, D. I. (2013). Exploring the Association Between Well-Being and Psychopathology in Adolescents. Behavior Genetics, 43(3), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-013-9589-7

Bass, J. K., Bolton, P. A., & Murray, L. K. (2007). Do not forget culture when studying mental health. The Lancet, 370(9591), 918–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61426-3

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bertha, E. A., & Balázs, J. (2013). Subthreshold depression in adolescence: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(10), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0411-0

Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375

Brady, E. U., & Kendall, P. C. (1992). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.244

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(1), 1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03

Caddick, H., Horne, B., Mackenzie, J., & Tilley, H. (2016). Investing in mental health in low-income countries (ODI Insights). Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/11184.pdf

Campbell, S., & Osborn, T. L. (2021). Adolescent Psychopathology and Psychological Wellbeing: A Network Analysis Approach. Bmc Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03331-x

Collins, P. Y., Patel, V., Joestl, S. S., March, D., Insel, T. R., Daar, A. S. … Walport, M. (2011). Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature, 475, 27

Cummings, C. M., Caporino, N. E., & Kendall, P. C. (2014). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 816

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Dumont, I. P., & Olson, A. L. (2012). Primary Care, Depression, and Anxiety: Exploring Somatic and Emotional Predictors of Mental Health Status in Adolescents. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110056

Essau, C. A. (2003). Comorbidity of anxiety disorders in adolescents. Depression and Anxiety, 18(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10107

Fatiregun, A. A., & Kumapayi, T. E. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among in-school adolescents in a rural district in southwest Nigeria. Journal of Adolescence, 37(2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.12.003

Fried, E. I., van Borkulo, C. D., Cramer, A. O. J., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Mental disorders as networks of problems: A review of recent insights. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z

Gleser, L. J. (1966). A note on the sphericity test. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 37(2), 464–467

Grant, K. E., Lyons, A. L., Finkelstein, J. A. S., Conway, K. M., Reynolds, L. K., O’Koon, J. H. … Hicks, K. J. (2004). Gender Differences in Rates of Depressive Symptoms Among Low-Income, Urban, African American Youth: A Test of Two Mediational Hypotheses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(6), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048066.90949.be

Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an Integration of Subjective Well-Being and Psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007219227883

Haroz, E. E., Ritchey, M., Bass, J. K., Kohrt, B. A., Augustinavicius, J., Michalopoulos, L. … Bolton, P. (2017). How is depression experienced around the world? A systematic review of qualitative literature. Social Science & Medicine, 183, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.030

Hill, B. D. (2011). The sequential Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin procedure as an alternative for determining the number of factors in common-factor analysis: A Monte Carlo simulation. Oklahoma State University

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55

Joseph, S., & Wood, A. (2010). Assessment of positive functioning in clinical psychology: Theoretical and practical issues. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 830–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.002

Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35(4), 401–415

Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg, E. A., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Well-Being. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000201

Khasakhala, L., Ndetei, D., Mutiso, V., Mbwayo, A., & Mathai, M. (2012). The prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in Nairobi public secondary schools: Association with perceived maladaptive parental behaviour. African Journal of Psychiatry, 15(2), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v15i2.14

Kilburn, K., Thirumurthy, H., Halpern, C. T., Pettifor, A., & Handa, S. (2016). Effects of a Large-Scale Unconditional Cash Transfer Program on Mental Health Outcomes of Young People in Kenya. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(2), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.023

King, N. J., & Bernstein, G. A. (2001). School Refusal in Children and Adolescents: A Review of the Past 10 Years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200102000-00014

Kirmayer, L. J., Gomez-Carrillo, A., & Veissière, S. (2017). Culture and depression in global mental health: An ecosocial approach to the phenomenology of psychiatric disorders. Social Science & Medicine, 183, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.034

Kleinman, A. (2004). Culture and Depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(10), 951–953. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp048078

Kleinman, A., & Good, B. J. (1985). Culture and depression: Studies in the anthropology and cross-cultural psychiatry of affect and disorder (16 vol.). Univ of California Press

Knafl, G. J., Dixon, J. K., O’Malley, J. P., Grey, M., Deatrick, J. A., Gallo, A. M., & Knafl, K. A. (2009). Analysis of Cross-Sectional Univariate Measurements for Family Dyads Using Linear Mixed Modeling. Journal of Family Nursing, 15(2), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840709331641

Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A New Depression Diagnostic and Severity Measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026

Lewis-Fernández, R., Aggarwal, N. K., Bäärnhielm, S., Rohlof, H., Kirmayer, L. J., Weiss, M. G. … Lu, F. (2014). Culture and Psychiatric Evaluation: Operationalizing Cultural Formulation for DSM-5. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 77(2), 130–154. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.130

Lewis-Fernández, R., & Díaz, N. (2002). The Cultural Formulation: A Method for Assessing Cultural Factors Affecting the Clinical Encounter. Psychiatric Quarterly, 73(4), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020412000183

Lewis-Fernández, R., & Krishan Aggarwal, N. (2013). Culture and Psychiatric Diagnosis. In R. D. Alarcón (Ed.), Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine (Vol. 33, pp. 15–30). S. KARGER AG. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348725

Liu, X., Peng, C., Yu, Y., Yang, M., Qing, Z., Qiu, X., & Yang, X. (2020). Association between sub-types of sibling bullying and mental health distress among Chinese children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 368

Magai, D. N., Malik, J. A., & Koot, H. M. (2018). Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Children and Adolescents in Central Kenya. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(4), 659–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0783-y

Manson, S. M., Shore, J. H., & Bloom, J. D. (1985). The depressive experience in American Indian communities: A challenge for psychiatric theory and diagnosis.Culture and Depression,331–368

Masuyama, A., Shinkawa, H., & Kubo, T. (2020). Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Japanese Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale Among Adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00368-z

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

McElroy, E., Fearon, P., Belsky, J., Fonagy, P., & Patalay, P. (2018). Networks of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Across Development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(12), 964–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.05.027

McGuinness Teena, M., Dyer Janyce, G., & Wade Ellin, H. (2012). Gender Differences in Adolescent Depression. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 50(12), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20121107-04

Ministry of Education, S. and T (2014). Basic education statistical booklet

Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2015). Ministry of Education, Science and Technology National Education Sector Plan (Basic Education Programme Rationale and Approach). Republic of Kenya. https://www.education.go.ke/index.php/downloads/category/17-policy-documents?download=82:natio

Mitchell, S., & Abbott, S. (1987). Gender and symptoms of depression and anxiety among Kikuyu secondary school students in Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 24(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(87)90149-3

Ndetei, D. M., Khasakhala, L., Nyabola, L., Ongecha-Owuor, F., Seedat, S., Mutiso, V. … Odhiambo, G. (2008). The prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and syndromes in Kenyan children and adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 20(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.2989/JCAMH.2008.20.1.6.491

Ndetei, D. M., Mutiso, V., Maraj, A., Anderson, K. K., Musyimi, C., & McKenzie, K. (2016). Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among primary school children in Kenya. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1090-6

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd edit.) mcgraw-hill. Hillsdale, NJ, 416

Osborn, T. L., Kleinman, A., & Weisz, J. R. (2021). Complementing standard Western measures of depression with locally co-developed instruments: A cross-cultural study on the experience of depression among the Luo in Kenya. Transcultural Psychiatry, 13634615211000556. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615211000555

Osborn, T. L., Rodriguez, M., Wasil, A. R., Venturo-Conerly, K. E., Gan, J., Alemu, R. G. … Weisz, J. R. (2020). Single-session digital intervention for adolescent depression, anxiety, and well-being: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial with Kenyan adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 657–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000505

Osborn, T. L., Venturo-Conerly, K. E., Arango, G., Roe, S., Rodriguez, E., Alemu, M. … Weisz, J. R. (2021). Effect of Shamiri Layperson-Provided Intervention vs Study Skills Control Intervention for Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents in Kenya: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1129

Osborn, T. L., Venturo-Conerly, K. E., Wasil, A. R., Schleider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2020). Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Social Support, and Demographic Factors Among Kenyan High School Students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(5), 1432–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01646-8

Osborn, T. L., Wasil, A. R., Venturo-Conerly, K. E., Schleider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2020). Group Intervention for Adolescent Anxiety and Depression: Outcomes of a Randomized Trial with Adolescents in Kenya. Behavior Therapy, 51(4), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.09.005

Othieno, C. J., Okoth, R. O., Peltzer, K., Pengpid, S., & Malla, L. O. (2014). Depression among university students in Kenya: Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.070

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. The Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36

Saluja, G., Iachan, R., Scheidt, P. C., Overpeck, M. D., Sun, W., & Giedd, J. N. (2004). Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms Among Young Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 760–765. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.8.760

Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 333–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2016). The state of the world’s children 2016: A fair chance for every child. United Nations Children’s Fund

Vigo, D., Thornicroft, G., & Atun, R. (2016). Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(2), 171–178

Weisz, J. R., Sigman, M., Weiss, B., & Mosk, J. (1993). Parent reports of behavioral and emotional problems among children in Kenya, Thailand, and the United States. Child Development, 64(1), 98–109

Weisz, J. R., Southam-Gerow, M. A., & McCarty, C. A. (2001). Control-related beliefs and depressive symptoms in clinic-referred children and adolscents: Developmental differences and model specificity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(1), 97

Weisz, J. R., Suwanlert, S., Chaiyasit, W., Weiss, B., Walter, B. R., & Anderson, W. W. (1988). Thai and American perspectives on over- and undercontrolled child behavior problems: Exploring the threshold model among parents, teachers, and psychologists. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.4.601

Williams, B., Onsman, A., & Brown, T. (2010). Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 8(3), https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.8.3.93

Winefield, H. R., Gill, T. K., Taylor, A. W., & Pilkington, R. M. (2012). Psychological well-being and psychological distress: Is it necessary to measure both? Psychology of Well-Being: Theory Research and Practice, 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2211-1522-2-3

World Health Organization. (2019). GHO | By category | Human resources—Data by country. WHO. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHHR?lang=en World Health Organization

Yara, P. O., & Wanjohi, C. (2011). Performance Determinants of Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) in Mathematics of Secondary Schools in Nyamaiya Division, Kenya. Asian Social Science, 7(2), p107. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n2p107

Yorbik, O., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D., Williamson, D. E., & Ryan, N. D. (2004). Clinical Characteristics of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Major Depressive Disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(12), 0–0

Zeng, G., Peng, K., & Hu, C. P. (2019). The Network Structure of Adolescent Well-Being Traits: Results From a Large-Scale Chinese Sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02783

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osborn, T.L., Venturo-Conerly, K.E., Gan, J.Y. et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms amongst kenyan adolescents: Psychometric Properties, Prevalence Rates and Associations with Psychosocial Wellbeing and Sociodemographic factors. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 50, 1471–1485 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-022-00940-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-022-00940-2