Abstract

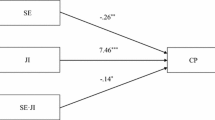

This paper puts forward a framework for evaluating the effects of governmental decentralization on the shadow economy and corruption. The theoretical analysis demonstrates that decentralization exerts both a direct and an indirect impact on the shadow economy and corruption. First, decentralization helps to mitigate government-induced distortions, thus limiting the extent of corruption and the informal sector in a direct way. Second, in more decentralized systems, individuals have the option to avoid corruption by moving to other jurisdictions, rather than going underground. This limits the impact of corruption on the shadow economy and implies that decentralization is also beneficial in an indirect way. As a result, our analysis documents a positive relationship between corruption and the shadow economy; however, this link proves to be lower in decentralized countries. To test these predictions, we developed an empirical analysis based on a cross-country database of 145 countries that includes different indexes of decentralization, corruption and shadow economy. The empirical evidence is consistent with the theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to Riker’s definition, a federal state implies “(1) [at least] two levels of government rule the same land and people, (2) each level has at least one area of action in which it is autonomous, and (3) there is some guarantee (even though merely a statement in the constitution) of the autonomy of each government in its own sphere.”

For a comprehensive analysis of the determinants of the informal sector, see Schneider and Enste (2000).

The production function implies that the productive input provided by the public sector is rival as well as essential for production.

The technology that characterizes the informal production in our framework does not require public services as a productive input. Here, we want to capture the idea that because of their illegal status, informal agents do not benefit from government-provided goods and services that can facilitate the production by allowing them full, enforceable property rights over their capital and output. For example, Loayza (1996) refers to the protection of the police and the legal and judicial system from crimes committed against the property. Moreover, informal producers are unable to take full advantage of other public services such as social welfare, skill-training programs, and government-sponsored credit facilities.

We are not considering here the case where individuals have to pay bribes to stay underground, which could generate a negative effect of corruption on the shadow economy. We do not allow for this possibility because we recognize that firms in the formal sector are more exposed to bureaucracy than those operating in the underground economy as emphasized in the literature.

As it will be clear below, the assumption that the sanction imposed to the producer is on net output rather than on the gross one simplifies the algebra without changing the results.

The linearity of the q(θ) simplifies the analysis but is not essential as the nonlinear effects of the inefficiency of bureaucracy and regulation on the level of shadow economy and corruption may be captured by the nonlinear effect of θ on the government efficiency in the provision of the productive goods and services (see below). It is also worth remarking that even though sanctions can be imposed independently on the respect of regulation (which we assume to be costless), the probability that they have to be paid depends on the degree of inefficiencies in bureaucracy and regulations (and can well be zero in a perfect well-functioning system). This is a simple way to capture the fact that higher bureaucratic inefficiencies and over-regulation increase the production costs in the formal sector relative to the informal one and allow bureaucrats to extract more bribes from producers. However, other mechanisms might generate the same results. For example, one may assume that producers have to choose between compliance or not and that more regulations and bureaucratic inefficiencies increase compliance costs. If the producers are allowed to bribe the bureaucrats to avoid penalties, then bribes will be increasing in the level of bureaucratic inefficiency and regulation.

In the proof of Lemma 2 we require that ω(θ) is not too concave in the sense that ω θθ /ω<(ω θ /ω)2. It is clear that the non-convexity of ω(θ), i.e. ω θθ ≤0, always satisfies this condition although it is not a necessary condition.

It is worth noting that a higher level of bureaucratic inefficiencies and regulations θ has two opposing effects on the payoff of the bureaucrats. On the one hand, it benefits the bureaucrats by allowing them to extract more bribes from the producers, but, on the other hand, it also reduces the production in the formal sector (i.e., y f is decreasing in θ) so lowering the rents they can extract from the producers.

The second-order condition is always satisfied as \(\partial^{2}y_{i} / \partial x_{i}^{2} = - \alpha(1 - \alpha)[(1 - aq\theta)(1 - t)(1 - x_{i})^{\alpha- 2}g^{1 - \alpha} + Ax_{i}^{\alpha- 2}] < 0\).

As there is no heterogeneity among citizens, the median voter coincides with the representative individual in the society.

All subnational units set the tax rate at the level t=1−α as this maximizes the income of the individuals as well as the net income in the formal sector, which in turn allows extracting more rents.

While some works have addressed the first point (even though the effects of decentralization have always been considered on the two phenomena separately, i.e. either on corruption or on the shadow economy), the latter result is new as it was never emphasized theoretically or empirically tested before.

This is the definition of corruption followed by Dreher and Schneider (2010).

Buehn and Schneider (2012a) estimate shadow economy by the MIMIC approach. Their structural equation includes variables as the share of direct taxation, fiscal freedom, business freedom and GDP per capita. It implies that high correlation between the estimates of the shadow economy and these variables is expected.

We replicate the empirical analysis using scores of Corr CPI and Corr WGI rescaled on theoretical bounds. Findings are qualitatively the same.

The authors estimate shadow economy as percentage of official GDP, where shadow economy includes “All market-based legal production of goods and services that are deliberately concealed from public authorities for any of the following reasons: (a) to avoid payment of income, value added, or other taxes; (b) to avoid payment of social security contributions; (c) to avoid having to meet certain legal labor market standards, such as minimum wages, maximum working hours, safety standards, etc.; (d) to avoid complying with certain administrative procedures, such as completing statistical questionnaires, or other administrative forms.” Buehn and Schneider’s (2012a: 141).

Data set is available at: http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/decentralization/fiscalindicators.htm#Formulas.

Examining the distributions of data across the countries, missing values on the second group for decentralization proxies are concentrated on the less developed countries. Seeing that these countries are frequently characterized by higher levels of corruption, there is thus the suspicion that the orthogonality between D3_Dec, Exp_Dec or Rev_Dec and the indexes of corruption may be due to a selection bias.

We also discriminate between centralized and decentralized countries according to the threshold of 50 % of the ratio between subnational and national expenditure and revenue. However, following this procedure, only 13 countries out of 145 can be defined as “decentralized.” In the authors’ view, it is an unreasonable binding criterion to identify the decentralized country.

According to D k ranking: Canada (7); Switzerland (7); Argentina (5); Brazil (3); India (3); Japan (3); Turkey (3); United Kingdom (3); Austria (1); Denmark (1); Ireland (1); Lithuania (1); Luxembourg (1); Malaysia (1); Mexico (1); Morocco (1); Pakistan (1); Russia (1); Sweden (1); United States (1).

It is taken as dropped dummy.

It is taken as dropped dummy.

We also include an index of international trade calculated as the percentage of exports and imports of goods and services on the gross national expenditure (t_open), but it is not statistically significant.

We use the natural logarithm of real GDP per capita calculated from both countries’ averages from 1999 to 2007 and values in 1998. Results of empirical tests of Propositions 3 and 4 are robust to these alternative GDP definitions.

TSLS estimator is not applied for models 4 and 5 because Corr Bribe1 and Corr Bribe2 have small sample sizes (i.e., about 40 observations), thus these estimates are unreliable.

To take into account the problem of endogeneity for the control variables, we include both dummy variables of legal origin and colonial dominance. The other control variables are taken by Eq. (26).

This index is one of the most used in literature and has the widest sample size.

References

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1999). Rents, competition and corruption. The American Economic Review, 89(4), 982–993.

Alexeev, M., & Habodaszova, L. (2012). Decentralization, corruption, and the shadow economy. Public Finance and Management, 12, 74–99.

Andvig, J. C. (2005). A house of straw, sticks or bricks’? Some notes on corruption empirics. Paper presented to IV Global Forum on Fighting Corruption and Safeguarding Integrity, Session Measuring Integrity, June 7, 2005.

Arikan, G. (2004). Fiscal decentralization: a remedy for corruption? International Tax and Public Finance, 11(2), 175–195.

Besley, T. (2006). Principled agents? The political economy of good government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2012a). Shadow economies around the world: novel insights, accepted knowledge, and new estimates. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 139–171.

Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2012b). Corruption and the shadow economy: like oil and vinegar, like water and fire? International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 172–194.

Choi, J. P., & Thum, M. (2005). Corruption and the shadow economy. International Economic Review, 46(3), 817–836.

Dell’Anno, R. (2007). Shadow economy in Portugal: an analysis with the MIMIC approach. Journal of Applied Economics, 10(2), 253–277.

Dell’Anno, R., & Schneider, F. (2008). A complex approach to estimate shadow economy: the structural equation modelling. In M. Faggini & T. Lux (Eds.), Coping with the complexity of economics. Springer-Verlag new economic windows series.

Dreher, A., & Schneider, F. (2010). Corruption and the shadow economy: an empirical analysis. Public Choice, 144(1), 215–238.

Dreher, A., Kotsogiannis, C., & McCorriston, S. (2009). How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance, 16(6), 773–796.

Echazu, L., & Bose, P. (2008). Corruption, centralization, and the shadow economy. Southern Economic Journal, 75(2), 524–537.

Elazar, D. J. (1995). From statism to federalism: a paradigm shift. Publius, 25(2), 5–18.

Enikolopov, R., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2007). Decentralization and political institutions. Journal of Public Economics, 91(2), 2261–2290.

Fan, S., Lin, C., & Treisman, D. (2009). Political decentralization and corruption: evidence around the world. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 14–34.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002a). Decentralization and corruption: evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83(3), 325–345.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002b). Decentralization and corruption: evidence from U.S. federal transfer programs. Public Choice, 113, 25–35.

Friedman, E., Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (2000). Dodging the grabbing hand: the determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 459–493.

Hayek, F. A. (1948). Individualism and economic order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Schleifer, A. (1997). The unofficial economy in transition. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 159–220.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (1998). Regulatory discretion and the unofficial economy. The American Economic Review, 88(2), 387–392.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (1999). Corruption, public finances and the unofficial economy (Policy Research Working Paper Series 2169). The World Bank.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Economics, Law and Organization, 15(1), 222–279.

Lederman, D., Loayza, N. V., & Soares, R. (2005). Accountability and corruption: political institutions matter. Economics and Politics, 17, 1–35.

Lessmann, C., & Markwardt, G. (2010). One size fits all? Decentralization, corruption, and the monitoring of bureaucrats. World Development, 38(4), 631–646.

Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: patterns of majoritarian and consensus government in twenty-one countries. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

Loayza, N. A. (1996). The economics of the informal sector. A simple model and some empirical evidence from Latin America. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 45, 129–162.

Mocan, N. (2004). What determines corruption? International evidence from micro data (NBER working paper 10460).

Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal federalism. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Oates, W. E. (1999). An essay on fiscal federalism. Journal of Economic Literature, 37, 1120–1149.

Panizza, U. (1999). On the determinants of fiscal centralization: theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 74, 97–139.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Munich lectures in economics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Riker, W. S. (1964). Federalism. Origin, operation, significance. Boston: Little Brown.

Rodden, J. (2004). Comparative federalism and decentralization: on meaning and measurement. Comparative Politics, 36(4), 481–500.

Shea, J. (1997). Instrument relevance in multivariate linear models: a simple measure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79, 348–352.

Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 77–114.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1993). Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617.

Søreide, T. (2005). Is it right to rank? Limitations, implications and potential improvements of corruption indices. Paper presented to IV Global Forum on Fighting Corruption and Safeguarding Integrity, Session Measuring Integrity, June 7, 2005.

Stegarescu, D. (2005). Public sector decentralization: measurement concepts and recent international trends. Fiscal Studies, 26(3), 301–333.

Teobaldelli, D. (2011). Federalism and the shadow economy. Public Choice, 146(3–4), 269–289.

Tiebout, C. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64, 416–424.

Torgler, B., Schneider, F., & Schaltegger, C. A. (2010). Local autonomy, tax morale and the shadow economy. Public Choice, 144(1), 293–321.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: a cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 399–457.

Treisman, D. (2006). Decentralization, fiscal incentives, and economic performance: a reconsideration. Economics and Politics, 18, 219–235.

Treisman, D. (2007). What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 211–244.

Treisman, D. (2008). Decentralization Data Set. Available at http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/treisman/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Proof of Lemma 2

From Lemma 1, it follows that politician’s monetary rent R is zero at t=0 and t=1 since x=1 in this case. R=0 also when θ=0 as there is no corruption and rents for the politician. This implies that the policy (t p ,θ p ) that maximizes monetary rents involves an intermediate level of the tax rate and a positive value of θ. The first-order conditions defining (t p ,θ p ) are the following:

Substituting (11) and (12) into respectively (30) and (31), we obtain

First, note that the sign of both derivatives is determined by the components within the square brackets. Rearranging terms in the square bracket of (33), we obtain the tax rate solving this equation to be t=1−α. From the square bracket of (32), it follows that there is a unique level of θ, which we call θ p , solving the equation

In fact, the first component is positive while the other three are negative since ω θ <0. Moreover, the first component is decreasing in θ as a higher level of θ increases the labor x employed in the shadow economy (see Lemma 1), while the other three components are increasing (in absolute value) in θ. This can be shown by considering the absolute value of these three components, and we can define

Then, we have that

since ω θ <0, ∂x/∂θ>0 and

from the assumption that function ω(θ) is “not too concave.” Finally, notice that θ p is not necessarily lower than 1 as it is possible that the square bracket of (32) is positive for all θ∈[0,1]. □

Proof of Lemma 3

From Lemma 2, it is straightforward that both politicians tax at the rate t 1=t 2=1−α as this maximizes their rent R as well as the net income y i of the individuals. Taking into account (11) and (12), the reaction functions of the two politicians with respect to θ are the following:

where ∂n 1/∂θ 1=∂h(⋅)/∂θ 1<0 and ∂n 2/∂θ 2=−∂h(⋅)/∂θ 2<0. Since the terms outside the square bracket are positive, the Nash equilibrium is the solution of the following system of equations:

Since the equilibrium is symmetric, θ 1=θ 2=θ r where θ r is the solution to the following equation:

From the comparison of (39) and (34) defining θ p , it follows that θ r <θ p since the left-hand side of both expressions are the same while the right-hand side of (39) is positive (as ∂n/∂θ=∂h(⋅)/∂θ<0). □

Proof of Proposition 4

Let us consider an exogenous increase (due to an increase in θ or in the fraction of product a in the formal sector that can be extorted by a bureaucrat) in the level of corruption B in a centralized state equal to dB. This leads to an increase in the labor employed in the shadow economy equal to

Now, let us consider a federal state with two equally populated jurisdictions, so that the population size in each of them is 1/2, and assume that the increase in corruption is not uniformly distributed in all jurisdictions. In particular, let us consider the extreme case where the increase in corruption is concentrated in jurisdiction 2 and it is equal to 2 dB, so that also the total increase in corruption in the federal state is equal to dB. As the individuals with lower migration costs find it optimal to move from jurisdiction 2 to jurisdiction 1, this increase in corruption implies an increase in the labor employed in the shadow economy in the federal state equal to

where ∂h(⋅)/∂B>0 represents the size of agents moving from jurisdiction 2 to jurisdiction 1. It is immediate that the same increase in corruption dB increases the shadow economy in a centralized state more than the increase in the federal state, and this difference is equal to

□

Appendix B

2.1 B.1 Database (1)

Symbol | Description | Source | Obs | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Av.CPI | Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ranks countries based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be. Average (1999–2005) | http://archive.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi | 145 | 1.2 | 9.8 |

Av.WGI | Control of Corruption: Reflects perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain. Average (1998–2005, not available data for 1999), | Worldwide Governance Indicators. World Bank. (www.govindicators.org) | 145 | −1.5 | 2.46 |

Av.Bribe1 | Percentage of firms expected to make informal payments to public officials to “get things done” with regard to customs, taxes, licenses, regulations, services, and the like. Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. [IC.FRM.CORR.ZS] based on Enterprise Surveys—World Bank. | 88 | 4.4 | 98.3 |

Av.ICRG | Political risk points by component “F-Corruption” (Scores 2005 + Scores 2011)/2. | International Country Risk Guide. The PRS Group, Inc. | 127 | 0.8 | 6.0 |

Av.CorrGIFT | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to public officials “to get things done”. Average (2005–2010) | Enterprise Surveys; World Bank. http://www.enterprisesurveys.org | 108 | 0.0 | 85.1 |

Av.CorrTAX | Percent of firms expected to give gifts in meetings with tax officials. Average (2005–2010) | 108 | 0.0 | 66.7 | |

Av.CorrGOV | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to secure government contract. Average (2005–2010) | 107 | 0.0 | 97.7 | |

Av.CorrLIC | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to get an operating license. Average (2005–2010) | 107 | 0.0 | 16.4 | |

Av.CorrIMP | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to get an import license. Average (2005–2010) | 107 | 0.0 | 88.2 | |

Av.CorrCONS | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to get a construction permit. Average (2005–2010) | 108 | 0.0 | 61.1 | |

Av.Corr.ELEC | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to get an electrical connection. Average (2005–2010) | 107 | 0.0 | 91.6 | |

Av.CorrWAT | Percent of firms expected to give gifts to get a water connection. Average (2005–2010) | 106 | 0.0 | 71.1 | |

Av.CorrPAST | Percent of firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request. Average (2005–2010) | 103 | 0.0 | 70.9 | |

Av.CorrREL | Percent of firms identifying corruption as a major constraint. Average (2005–2010) | 108 | 0.0 | 65.2 | |

Av.CorrJUS | Percent of firms identifying the courts system as a major constraint. Average (2005–2010) | 108 | 0.0 | 68.9 | |

INF_comp | Percent of firms competing against unregistered or informal firms. Average (2005–2010) | 108 | 0.0 | 89.8 | |

INF_rel | Percent of firms identifying practices of competitors in the informal sector as a major constraint. Average (2005–2010) | 108 | 0.0 | 72.4 | |

Shadow | Shadow Economy as percentage of official GDP. Average (1999–2007) | 145 | 8.54 | 66.1 | |

Exp_Dec | 100∗{1-[Total Expenditure, Noncash (Cen. Govt.)/Total Expenditure, Noncash (Gen. Govt.)]}. Average (1999–2007) | Government Finance Statistics. IMF | 45 | 12.5 | 129.5 |

Rev_Dec | 100∗{1-[Revenue, Noncash (Cen. Govt.)/Revenue, Noncash (Gen. Govt.)]}. Average (1999–2007) | Government Finance Statistics. IMF | 48 | 12.4 | 130.8 |

D1_Fed | Classified as a federation by Elazar (1995) and updated by Treisman (2007) by adding Ethiopia, Serbia-Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, which became federal after Elazar’ article. (Federal =1.) | Treisman (2006). Available from: www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/treisman/Papers/what_have_we_learned_data.xls [Fedelaz] | 141 | 0 | 1 |

D2_Fed | Persson and Tabellini (2003). (Federal =1.) | Available from: http://didattica.unibocconi.it/mypage/index.php?IdUte=48805&idr=4273, [Federal] | 81 | 0 | 1 |

D3_Fed | Dummy variable =1 if (a) constitution reserves decision making on at least one topic exclusively to subnational legislatures and/or (b) constitution assigns to subnational legislatures exclusive right to legislate on issues that it does not specifically assign to one level of government. | Treisman (2008) [Auton.] | 68 | 0 | 1 |

DT_Fed | Dummy variable: Decentralized =1. (See paragraph 4.1 for details.) | Own estimation based on GFS (IMF) and Treisman (2007, 2008) Persson and Tabellini (2003) | 140 | 0 | 1 |

2.2 B.2 Database (2)

Symbol | Description | Source | Obs | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

BritCol | Former British colony | Treisman (2006). Available from: www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/treisman/Papers/what_have_we_learned_data.xls. We correct four digit errors in this file. | 134 | 0 | 1 |

FrenCol | Former French colony | 134 | 0 | 1 | |

SpanPorC | Former Spanish or Portuguese colony | 134 | 0 | 1 | |

OtherCol | Former colony of state other than Britain, France, Spain, or Portugal, | 134 | 0 | 1 | |

NonCol | Never a colony | 134 | 0 | 1 | |

LegBritish | legal origin: British | GDN Growth Database, Available from: www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/treisman/Papers/what_have_we_learned_data.xls | 126 | 0 | 1 |

LegFren | legal origin: French | 126 | 0 | 1 | |

LegSoc | legal origin: Socialist | 126 | 0 | 1 | |

LegGerm | legal origin: German | 126 | 0 | 1 | |

LegScand | legal origin: Scandinavian | 126 | 0 | 1 | |

LGDPcap | Logarithm of GDP per capita (constant 2000 US$). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators Log[NY.GDP.PCAP.KD] | 143 | 4.5 | 10.8 |

FDI | Average from Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. [BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS] | 143 | −6.5 | 388.4 |

t_open | (Exports of goods and services (current LCU)+Imports of goods and services (current LCU)/(Gross national expenditure (current LCU). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. 100∗[(NE.EXP.GNFS.CN+NE.IMP.GNFS.CN)/NE.DAB.TOTL.CN] | 136 | 0.6 | 514.8 |

School | School enrollment, secondary (% gross). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. [SE.SEC.ENRR] | 135 | 8.4 | 152.6 |

Gov_size | General government final consumption expenditure (current LCU)/ Final consumption expenditure (current LCU). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators 100∗[NE.CON.GOVT.CN /NE.CON.TOTL.CN] | 116 | 5.4 | 53.0 |

Self | Self-employed, total (% of total employed). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators [SL.EMP.SELF.ZS] | 121 | 0.9 | 94.7 |

T_rev | Tax revenue (% of GDP). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. [GC.TAX.TOTL.GD.ZS] | 117 | 0.2 | 45.2 |

Urban | Urban population (% of total). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. [SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS] | 142 | 9.0 | 100 |

Wom_gov | Women in government at ministerial level (as % of total) 2001 | Treisman (2006). Available from: www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/treisman/Papers/what_have_we_learned_data.xls. [womgov01]. Original Source: UNDP, Human Development Report, 2004 | 96 | 0 | 47.4 |

Lab_part | Labor participation rate, total (% of total population ages 15+). Average (1999–2007) | World Development Indicators. [SL.TLF.CACT.ZS] | 142 | 40.4 | 89.2 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dell’Anno, R., Teobaldelli, D. Keeping both corruption and the shadow economy in check: the role of decentralization. Int Tax Public Finance 22, 1–40 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9298-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9298-4