Abstract

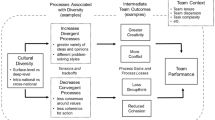

The aim of this paper is to show that the nascent field of ethics of collegiality may considerably benefit from a symbiosis with virtue and vice epistemology. We start by bringing the epistemic virtue and vice perspective to the table by showing that competence, deemed as an essential characteristic of a good colleague (Betzler & Löschke 2021), should be construed broadly to encompass epistemic competence. By endorsing the anti-individualistic stance in epistemology as well as context-specificity of epistemic traits, we show how the individual vice of a colleague can have a positive epistemic outcome for the team while individual virtue can be damaging if all team members share it thereby contributing to the negative epistemic outcome. We argue that the evaluation and analysis of collegial relationships should be done through one’s contribution to the team dynamics: without this collectivist perspective, the ethics of collegiality cannot aspire to become encompassing normative theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Monika Betzler and Jörg Löschke, “Collegial Relationships,” Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 24 (2021): 213–229; Kevin Reuter, Jörg Löschke and Monika Betzler, “What is a Colleague? The Descriptive and Normative Dimension of a Dual-character Concept,” Philosophical Psychology 33 (2020): 997–1017.

See Joshua Knobe, Sandeep Prasada and George E Newman, “Dual Character Concepts and the Normative Dimension of Conceptual Representation,” Cognition 127 (2013): 242–257.

See Boudewijn De Bruin, “Ethics management in banking and finance,” in N. Morris & D. Vines (eds.), Capital Failure: Rebuilding Trust in Financial Services (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 255–276; Boudewijn De Bruin Ethics and the Global Financial Crisis: Why Incompetence is Worse than Greed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

See Monika Betzler and Jörg Löschke, op. cit.

See Quassim Cassam, “Vice Epistemology,” The Monist 99 (2016): 159–180.; Quassim Cassam, Vices of the Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); Heather Battaly, “Varieties of Epistemic Vice,” in J. Matheson and R. Vitz (eds.), The Ethics of Belief (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 51–76; Ian James Kidd, “Charging Others with Epistemic Vice,” The Monist 99 (2016): 181–197; Ian James Kidd, Heather Battaly and Quassim Cassam, Vice Epistemology (London: Routledge, 2020).

See Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics (c. 350 BCE), trans. D. Ross (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Linda Zagzebski, Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Of course, this does not imply that every aspect of virtue epistemology has an ethical background. A decade before Linda Zagzebski’s seminal book which contributed to inaugurating the subfield in the mainstream epistemology, Sosa reached for the notion of “intellectual virtues’’ to help dissolving the seemingly never-ending debate between foundationalists and coherentists in epistemology (See Ernest Sosa, “The Raft and the Pyramid: Coherence versus Foundations in the Theory of Knowledge,” Midwest Studies in Philosophy 5 (1980): 3–25.). In that sense, intellectual virtues were merely an imported tool that should serve a new purpose in traditional analytic epistemology. Our point here is similar to Baehr, who gives an excellent overview of the structural similarities between virtue ethics and virtue epistemology (See Jason Baehr, “Virtue Epistemology, Virtue Ethics, and the Structure of Virtue” in H Battaly (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Virtue Epistemology (New York: Routledge, 2018): pp. 144–162). However, it is worth noting that when philosophers pay attention to the analysis of specific virtues, ethical background becomes either implicitly or explicitly assumed (for instance, see Nancy E. Snow, “Intellectual Humility,” in: H Battaly (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Virtue Epistemology (New York: Routledge, 2018): 178–196; Laura Beeby, “Epistemic Justice: Three Models of Virtues” in: H Battaly (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Virtue Epistemology (New York: Routledge, 2018): 232–244; Ian James Kidd, “Epistemic Courage and the Harms of Epistemic Life.” in: H Battaly (ed.) Routledge Handbook of Virtue Epistemology (New York: Routledge, 2018): 244–256.

See Jason Baehr, “Educating for Intellectual Virtues: From Theory to Practice,”Journal of the Philosophy of Education 47 (2013): 248–262; De Bruin (2014), op. cit.; Christopher Baird and Thomas S Calvard, “Epistemic Vices in Organizations: Knowledge, Truth, and Unethical Conduct,” Journal of Business Ethics 160(2019): 263–276.

Betzler & Löschke, op. cit.

Baird & Calvard outline the interface between business ethics and applied vice epistemology, i.e., how vices such as malevolence, insouciance, hubris and justice impact organizations (See Baird & Calvard, op. cit.). Nonetheless, whereas their focus is on institutional and organizational aspects, we pay attention to teams and work collectives that constitute such organizations and institutions. In other words, we provide a fine-grained analysis of collegial relationships akin to Betzler & Löschke, and leave the coarse-grained analysis of links between business ethics and the ethics of collegiality for future work (See Betzler & Löschke, op. cit.).

We endorse the broad definition of Palermos and Pritchard who see epistemic group agents as “groups of individuals who exist and gain knowledge in virtue of a shared common cognitive character that primarily consists of a distributed cognitive ability” (See Orestis Palermos and Duncan Pritchard, “Extended Knowledge and Social Epistemology,” Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 2 (2013): 105–120, p. 115). However, we see “collectives” as groups of colleagues and coworkers who gain knowledge and act in virtue of a shared workload and in accordance with their epistemic profile. Nonetheless, we use the two terms interchangeably throughout the paper, along with the term “team” or “teamwork”, since all these point to the anti-individualist perspective that we want to emphasize.

See Christopher Hookway, “How to Be a Virtue Epistemologist.” in: M. DePaul & L. Zagzebski (eds.), Intellectual Virtue: Perspectives from Ethics and Epistemology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003): 183–202; Reza Lahroodi “Collective Epistemic Virtue,” Social Epistemology 21 (2007): 281–297; Anita Konzelmann Ziv, “Collective Epistemic Agency: Virtue and the Spice of Vice,” in: H.B. Schmid, D. Sites & M. Webe (eds.), Collective Epistemology (Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, 2011): 45–72; Neil Levy and Mark Alfano, “Knowledge from Vice: Deeply Social Epistemology,” Mind 129(2020): 887–915.

See Jennifer Lackey, The Epistemology of Groups (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

See Ziv, op. cit.; Hookway, op. cit.

Hookway, op. cit., p. 189.

What counts when we assess the epistemic and ethical correctness of a group’s behavior is whether side-effects were intentionally or non-intentionally vicious. If the side-effects are non-intentionally vicious and promote positive conduct of a group, as was the case in Hookway’s original example, then the epistemic vice can be regarded as an exotic spice that contributes to a well-cooked dish (Ziv, op. cit., p. 63). Konzelmann Ziv’s account is particularly apt for linking with recently coined terms such as epistemic blameworthiness (Cassam 2019, op. cit.). In the case of intentionally vicious side-effects, one has the right to hold group behavior epistemically (and morally) responsible without necessarily deferring to considerations regarding the group’s motives.

See Kevin Zollman, “The Epistemic Benefit of Transient Diversity,” Erkenntnis 72 (2010): 17–35; Bo Xu, Renjing Liu and Zhengwen He, “Individual Irrationality, Network Structure, and Collective Intelligence: An Agent-Based Simulation Approach,” Complexity 21 (2016): 44–54; Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, “Why Do Humans Reason? Arguments for an Argumentative Theory,’ Behavioral and Brain Sciences 34 (2o11): 57–111.

Smart, PR “Mandevillian Intelligence: From Individual Vice to Collective Virtue,” in: A.J. Carter, A. Clark, J. Kallestrup, O.J. Palermos, and D. Pritchard (eds.), Socially Extended Epistemology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) 253–274, p 256.

See Mandi Astola, “Mandevillian Virtues,” Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 24 (2021): 19–32; Smart, op. cit.

See Chun Wei Choo, The Inquiring Organization: How Organizations Acquire Knowledge and Seek Information (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); Baird & Calvard, op. cit.

See Heather Battaly, “Quitting, Procrastinating, and Slacking Off,” in: Kidd, I. J., Battaly, H., & Cassam, Q. (eds), Vice Epistemology (London: Routledge, 2020): 167–189.

See Hal Arkes and Peter Ayton, “The Sunk Cost and Concorde Effects: Are Humans Less Rational than Lower Animals?“ Psychological Bulletin 125(1999): 591–600; Hal R Arkes and Catherine Blumer (1985) “The Psychology of Sunk Cost,“ Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 35(1985): 124–140; Howard Garland and Donald E Conlon (1998) “Too Close to Quit: The Role of Project Completion in Maintaining Commitment,“ Journal of Applied Social Psychology 28 (1998): 2025–2048.

See Joyce C Havstad and Adam N Smith, “Fossils with Feathers and Philosophy of Science,“ Systematic Biology 68 (2019): 840–861.

Battaly 2020, op. cit., p. 171. The same thing was pointed out by the anonymous reviewer.

See Corina Haita-Falah, “Sunk-cost Fallacy and Cognitive Ability in Individual Decision-Making,“ Journal of Economic Psychology 58 (2017): 44–59.

We thank the anonymous reviewer for pressing us to address this line of argument that goes against our claims.

Mark Alfano, Character as Moral Fiction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Battaly 2020, op. cit., p. 181; Alison Suen, Why is it Okay to be a Slacker (Routledge, 2021), p. 54.

See John Perry, The Art of Procrastination (New York: Workman Publishing, 2012).

Suen, op. cit., p. 136.

See Suen, op. cit., Ch. 7.

See Mark Alfano, Kathryn Iurino, Paul Stey, Brian Robinson, Markus Christen, Feng Yu and Daniel Lapsley, “Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Intellectual Humility,” PLoS One 12 (2017): 1–28; Matteo Colombo, Kevin Strangmann, Lieke Houkes, Zhasmina Kostadinova and Mark J Brandt, “Intellectually Humble, but Prejudiced People. A Paradox of Intellectual Virtue,” Review of Philosophy and Psychology 12 (2021): 353–371; Jack MC Kwong, “Open-mindedness as a Critical Virtue,” Topoi 35 (2016): 403–411; Jack MC Kwong JMC (2021) The Social Dimension of Open-Mindedness. Erkenntnis (2021), doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00348-8; Ian M Church and Peter L Samuelson, Intellectual Humility: An Introduction to Philosophy and Science (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2017); Mark Alfano, Michael P Lynch and Alessandra Tanesini, The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Humility (London, NY: Routledge, 2021).

See Robert C Roberts, W Jay Wood, Intellectual Virtues: An Essay in Regulative Epistemology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007); Dennis Whitcomb, Heather Battaly, Jason Baehr and Daniel Howard-Snyder, “Intellectual Humility: Owning Our Limitations,“ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 94 (2017): 509–539.

See Duncan Pritchard “Intellectual Humility and the Epistemology of Disagreement,“ Synthese 198 (2021): 1711–1723.

Lu Hong and Scott E Page, “Groups of Diverse Problem Solvers Can Outperform Groups of High-ability Problem Solvers,“ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101 (2004): 16385–16389.

See Francesca Gino and Dan Ariely, “The Dark Side of Creativity: Original Thinkers can be More Dishonest,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102 (2012): 445–459.

See Betzler & Löschke, op. cit.

We thank the anonymous reviewer for this insightful remark, although we believe that the full response to this remark is out of the scope of this paper and merits a study on its own.

See Angela L Duckworth, Christopher Peterson, Michael D Matthews and Dennis R Kelly, “Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals,“ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92 (2007): 1087–1101; Benjamin R Meagher, Joseph C Leman, Caitlyn A Heidenga, Michala R Ringquist and Wade C Rowatt, “Intellectual Humility in Conversation: Distinct Behavioral Indicators of Self and Peer Ratings,“ The Journal of Positive Psychology 16 (2021): 417–429; Colombo M, Strangmann K, Houkes L, Kostadinova Z, & Brandt MJ, op. cit.; Alfano M, Iurino K, Stey P, Robinson B, Christen M, Yu F, Lapsley D (2017), op. cit.; Megan Haggard, Wade C Rowatt, Joseph C Leman, Benjamin Meagher, Courtney Moore, Thomas Fergus, Dennis Whitcomb, Heather Battaly, Jason Baehr, Jason, Dan Howard-Snyder, “Finding Middle Ground between Intellectual Arrogance Intellectual Servility: Development and Assessment of the Limitations-owning Intellectual Humility Scale,“ Personality and Individual Differences 124 (2018): 184–193; Vlast Sikimić, Tijana Nikitović, Miljan Vasić and Vanja Subotić, “Do Political Attitudes Matter for Epistemic Decisions of Scientists?“ Review of Philosophy and Psychology 12 (2020): 775–801; Marco Meyer, Mark Alfano and Boudewijn de Bruin, “The Development and Validation of the Epistemic Vice Scale,“ Review of Philosophy and Psychology (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-021-00562-5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Berber, A., Subotić, V. The Anti-Individualistic Turn in the Ethics of Collegiality: Can Good Colleagues Be Epistemically Vicious?. J Value Inquiry (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-022-09922-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-022-09922-5