Abstract

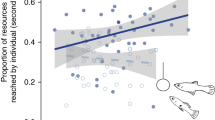

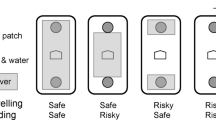

A major consequence of group living is that foragers may rely on social information in addition to ecological information to locate feeding sites. Although conspecifics can provide cues as to the spatial location of food patches, individual foraging decisions also must include some assessment of the likelihood of obtaining access to a resource other group members seek. This likelihood differs in the 2 models generally proposed to explain intragroup social foraging: the information-sharing model and the producer-scrounger model. We conducted an experimental field study on wild groups of emperor (Saguinus imperator) and saddleback (S. fuscicollis) tamarins to determine the foraging strategies adopted by individual group members and their relationship to social rank, food intake, and the ability to use ecological and social information in making intra-patch foraging decisions. Individual tamarins applied different behavioral strategies compatible with a finder-joiner paradigm to solve foraging problems. About half of the individuals in each study group initiated 74%–90% of all food searches and acted as finders. Most alpha individuals adopted a joiner strategy by monitoring the activities of others' to obtain a reward. The individual arriving first at a reward platform enjoyed a finder's advantage. Despite differences in search effort, both finders and joiners presented similar abilities in learning to associate ecological cues with the presence of food rewards at our experimental feeding stations. We conclude that within a group foraging context, tamarins integrate social and ecological information in decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barnard, C. J., and Sibly, R. M. (1981). Producers and scroungers: A general model and its application to captive flocks of house sparrows. Anim. Behav. 29: 543–550.

Barta, Z., and Giraldeau, L. A. (1998). The effect of dominance on the use of alternative foraging tactics: A phenotype-limited producing-scrounging game. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 42: 217–223.

Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2000). Cognitive Aspects of Within-Patch Foraging Decisions in Wild Diurnal and Nocturnal New World Monkeys, PhD thesis, University of Illinois, Urbana. Available from: University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, MI: 9955588.

Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2003). Sexual selection and foraging behavior in male and female tamarins and marmosets. In Jones, C. B. (ed.), Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Primates: New Perspectives and Directions, American Society of Primatologists, Norman, pp. 455–475.

Bicca-Marques, J. C., and Garber, P. A. (2003). Experimental field study of the relative costs and benefits to wild tamarins (Saguinus imperator and S. fuscicollis) of exploiting contestable food patches as single- and mixed-species troops. Am. J. Primatol. 60:139–153.

Bicca-Marques, J. C, and Garber, P. A. (2004). The use of spatial, visual, and olfactory information during foraging in wild nocturnal and diurnal anthropoids: A field experiment comparing Aotus, Callicebus, and Saguinus. Am. J. Primatol. 62: 171–187.

Boinski, S. (2000). Social manipulation within and between troops mediates primate group movement. In Boinski, S., and Garber, P. A. (eds.), On the Move: How and Why Animals Travel in Groups, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 421–469.

Bolen, R. H. (1998). The Use of Olfactory Cues, Spatial Memory, and Social Information in Foraging by Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus apella) and Owl Monkeys(Aotus nancymae), PhD thesis, University of Florida, Coral Gables.

Box, H. O., Röhrhuber, B., and Smith, P. (1995). Female tamarins (Saguinus—Callitrichidae) feed more successfully than males in unfamiliar foraging tasks. Behav. Proc. 34: 3–12.

Di Bitetti, M. S., and Janson, C. H. (2001). Social foraging and the finder's share in capuchin monkeys, Cebus apella. Anim. Behav. 62: 47–56.

Drapier, M., Ducoing, A. M., and Thierry, B. (1999). An experimental study of collective performance at a task in Tonkean macaques. Behaviour 136: 99–117.

Drea, C. M. (1998). Status, age, and sex effects on performance of discrimination tasks in group-tested rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J. Comp. Psychol. 112: 170–182.

Drea, C. M., and Frank, L. G. (2003). The social complexity of spotted hyenas. In de Waal, F. B. M., and Tyack, P. L. (eds.), Animal Social Complexity: Intelligence, Culture, and Individualized Societies, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 121–148.

Drea, C. M., and Wallen, K. (1999). Low-status monkeys “play dumb” when learning in mixed social groups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 12965–12969.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evol. Anthropol. 6: 178–190.

Encarnación, F., Moya, L., Soini, P., Tapia, J., and Aquino, R. (1990). La captura de Callitrichidae (Saguinus y Cebuella) en la Amazonia Peruana. In Castro-Rodríguez, N. E. (ed.), La Primatología en el Peru, Proyecto Peruano de Primatologia, Iquitos, pp. 45–56.

Erhart, E. M., and Overdorff, D. J. (1999). Female coordination of group travel in wild Propithecus and Eulemur. Int. J. Primatol. 20: 927–940.

Fragaszy, D. M., and Boinski, S. (1995). Patterns of individual diet choice and efficiency of foraging in wedge-capped capuchin monkeys (Cebus olivaceus). J. Comp. Psychol. 109: 339–348.

Garber, P. A. (1993). Feeding ecology and behaviour of the genus Saguinus. In Rylands, A. B. (ed.), Marmosets and Tamarins: Systematics, Ecology and Behaviour, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 273–295.

Garber, P. A. (1997). One for all and breeding for one: Cooperation and competition as a tamarin reproductive strategy. Evol. Anthropol. 5: 187–199.

Garber, P. A. (2000). Evidence for the use of spatial, temporal, and social information by primate foragers. In Boinski, S., and Garber, P. A. (eds.), On the Move: How and Why Animals Travel in Groups, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 261–289.

Garber, P. A., and Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2002). Evidence of predator sensitive foraging in small- and large-scale space in free-ranging tamarins (Saguinus fuscicollis, Saguinus imperator, and Saguinus mystax). In Miller, L. E. (ed.), Eat or Be Eaten: Predator Sensitive Foraging in Primates, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 138–153.

Garber, P. A., and Dolins, F. L. (1996). Testing learning paradigms in the field: Evidence for use of spatial and perceptual information and rule-based foraging in wild moustached tamarins. In Norconk, M., Rosenberger, A. L., and Garber, P. A. (eds.), Adaptive Radiation of Neotropical Primates, Plenum Press, New York, pp. 201–216.

Garber, P. A., and Paciulli, L. M. (1997). Experimental field study of spatial memory and learning in wild capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus). Folia Primatol. 68: 236–253.

Giraldeau, L. A., and Beauchamp, G. (1999). Food exploitation: Searching for the optimal joining policy. TREE 14: 102–106.

Giraldeau, L. A., and Caraco, T. (2000). Social Foraging Theory, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Janson, C. (1985). Aggressive competition and individual food consumption in wild brown capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 18: 125–138.

Kamil, A. C. (1994). A synthetic approach to the study of animal intelligence. In Real, L. A. (ed.), Behavioral Mechanisms in Evolutionary Ecology, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 11–45.

Koops, M. A., and Giraldeau, L. A. (1996). Producer-scrounger foraging games in starlings: A test of rate-maximizing and risk-sensitive models. Anim. Behav. 51: 773–783.

Leca, J. B., Gunst, N., Thierry, B., and Petit, O. (2003). Distributed leadership in semifree-ranging white–-faced capuchin monkeys. Anim. Behav. 66: 1045–1052.

Lehner, P. N. (1996). Handbook of Ethological Methods, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Liker, A., and Barta, Z. (2002). The effects of dominance on social foraging tactic use in house sparrows. Behaviour 139: 1061–1076.

Martin, P., and Bateson, P. (1993). Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Milton, K. (1981). Diversity of plant foods in tropical forests as a stimulus to mental development in primates. Am. Anthropol. 83: 534–548.

Milton, K. (2000). Quo Vadis? Tactics of food search and group movement in primates and other animals. In Boinski, S., and Garber, P. A. (eds.), On the Move: How and Why Animals Travel in Groups, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 375–417.

Mottley, K., and Giraldeau, L. A. (2000). Experimental evidence that group foragers can converge on predicted producer-scrounger equilibria. Anim. Behav. 60: 341–350.

Nunes, C. A., Bicca-Marques, J. C., Schacht, K., and Araripe, A. C. A. (1998). Reaction of wild emperor tamarins to the presence of a snake. Neotrop. Primates 6: 20.

Ranta, E., Peuhkuri, N., Laurila, A., Rita, H., and Metcalfe, N. B. (1996). Producers, scroungers and foraging group structure. Anim. Behav. 51: 171–175.

Rita, H., Ranta, E., and Peuhkuri, N. (1997). Group foraging, patch exploitation time and the finder's advantage. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 40: 35–39.

Robinette, R., and Ha, J. C. (2003). Effects of ecology and prey characteristics on the use of alternative social foraging tactics in crows, Corvus caurinus. Anim. Behav. 66: 309–316.

Robinson, J. G. (1981). Spatial structure in foraging groups of wedge-capped capuchin monkeys, Cebus nigrivittatus. Anim. Behav. 29: 1036–1056.

Santos, F. G. A., Salas, E. R., Bicca-Marques, J. C., Calegaro-Marques, C., and Farias, E. M. P. (1999). Cloridrato de tiletamina associado com cloridrato de zolazepam na tranquilização e anestesia de calitriquídeos (Mammalia, Primates). Arq. Brasil Med. Vet. Zootec. 51: 539–545.

Silveira, G., Bicca-Marques, J. C., and Nunes, C. A. (1998). On the capture of titi monkeys (Callicebus cupreus) using the Peruvian method. Neotrop. Primates 6: 114–115.

Smith, A. C., Buchanan-Smith, H. M., Surridge, A. K., and Mundy, N. I. (2003). Leaders of progressions in wild mixed-species troops of saddleback (Saguinus fuscicollis) and mustached tamarins (S. mystax), with emphasis on color vision and sex. Am. J. Primatol. 61: 145–157.

Smolker, R. (2000). Keeping in touch at sea: Group movement in dolphins and whales. In Boinski, S., and Garber, P. A. (eds.), On the Move: How and Why Animals Travel in Groups, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 559–586.

Stahl, J., Tolsma, P. H., Loonen, M. J. J. E., and Drent, R. H. (2001). Subordinates explore but dominants profit: Resource competition in high Arctic barnacle goose flocks. Anim. Behav. 61: 257–264.

Sussman, R. W., and Garber, P. A. (1987). A new interpretation of the social organization and mating system of the Callitrichidae. Int. J. Primatol. 8: 73–92.

Terborgh, J. (1983). Five New World Primates: A Study in Comparative Ecology, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Tiebout, H. M. (1996). Costs and benefits of interspecific dominance rank: Are subordinates better at finding novel food locations? Anim. Behav. 51: 1375–1381.

Vickery, W. L., Giraldeau, L. A., Templeton, J. J., Kramer, D. L., and Chapman, C. A. (1991). Producers, scroungers, and group foraging. Am. Nat. 137: 847–863.

Visalberghi, E., and Tomasello, M. (1998). Primate causal understanding in the physical and psychological domains. Behav. Proc. 42: 189–203.

Windfelder, T. L. (1997). Polyspecific Association and Interspecific Communication Between Two Neotropical Primates: Saddle-Back Tamarins (Saguinus fuscicollis) and Emperor Tamarins (Saguinus imperator). PhD thesis, Duke University, Durham. Available from: University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, MI: 9818537.

Winterhalder, B. (1996). Social foraging and the behavioral ecology of intragroup resource transfers. Evol. Anthropol. 5: 46–57.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bicca-Marques, J.C., Garber, P.A. Use of Social and Ecological Information in Tamarin Foraging Decisions. Int J Primatol 26, 1321–1344 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-005-8855-9

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-005-8855-9